Sweden, Russia and the Great Northern War

by

Frank Smitha

Maps: The New Cambridge Modern History Atlas, Cambridge, 1970

Cambridge Illustrated

Atlas. Warfare: Renaissance to revolution (1492-1792), Cambridge, 1996

Sweden Defeats Peter the Great Sweden Defeats Peter the Great

In 1697, Sweden acquired a new monarch:

a 15-year-old who took the name Charles XII. Charles had been taught to

follow the warrior tradition of his father, including fencing, horseback

riding and military strategy. He was a boy with courage and intelligence, and

he was challenged by rivals for territory, who were encouraged by what they

believed was Sweden's

new weakness resulting from the death of its previous king, Charles XI. Denmark's monarch, Christian V (who also ruled

Norway) wanted to win back

from the Swedish monarchy the territory

of Skåne

(just east of Copenhagen),

which his family had lost in 1658. The Elector of Saxony, a German named Augustus, was also interested in expanding against

Swedish interests. It was an old story: territorial disputes among

kings.

Augustus was born in Dresden

- a part of what was still called the Holy Roman Empire.

In the manner of Europe's interrelated

royalty he was a candidate for the Polish throne. For this he became a Roman

Catholic, displeasing his Protestant subjects in Saxony.

He won the Polish throne over a rival contestant: the Prince of Conti

- a Bourbon prince from France.

In 1699, Augustus formed an alliance with the new king of Denmark: Christian V's twenty-nine

year-old son, Frederick IV - a cousin to Charles XII of Sweden. And,

from Poland, Augustus

wanted to expand his rule to Livonia, where

Germanic nobles were unhappy with Swedish rule.

Another interested in expanding at the expense of Sweden was Russia's monarch, Peter the

Great. He was a friend of the Swedish monarchy until 1699, having sworn to

observe all treaties between his kingdom and the kingdom of Sweden.

Then he saw opportunity in joining an alliance with Augustus and Frederick,

justifying his decision by complaining that the Swedes had stolen lands of

his ancestors - a fiction regarding Ingria, Karelia, Livonia and Estonia. And he complained of mistreatment

he had suffered during his visit to Riga, when

he had been examining too closely Riga's

fort.

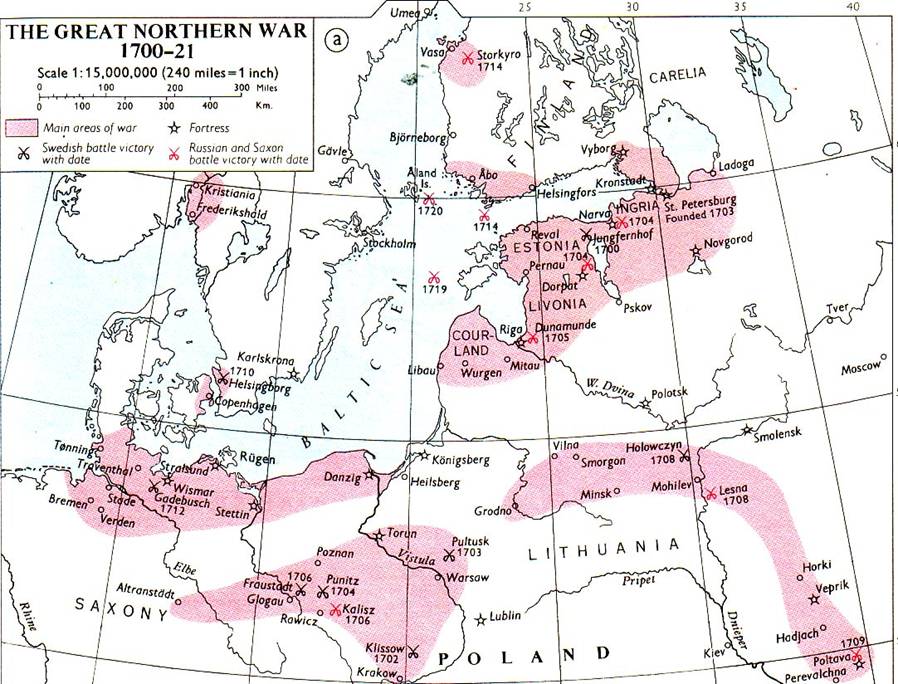

In August, 1700, Charles XII - then eighteen

- responded to the challenge from his neighbors by landing troops a few miles

north of Copenhagen, and, without putting up a

fight, Frederick

agreed to commit no future hostilities against his cousin.

Charles then rushed to Livonia

with 8,000 men, arriving at Pernau on October 6. He

turned north and eastward, marching across boggy roads, wasteland and

difficult passes to do battle against the Russians. At a pass called Pyhåjoggi, with 400 horsemen he put to flight 6,000

Russian troops. On November 19 his army reached Laena,

a little village about nine miles from Narva.

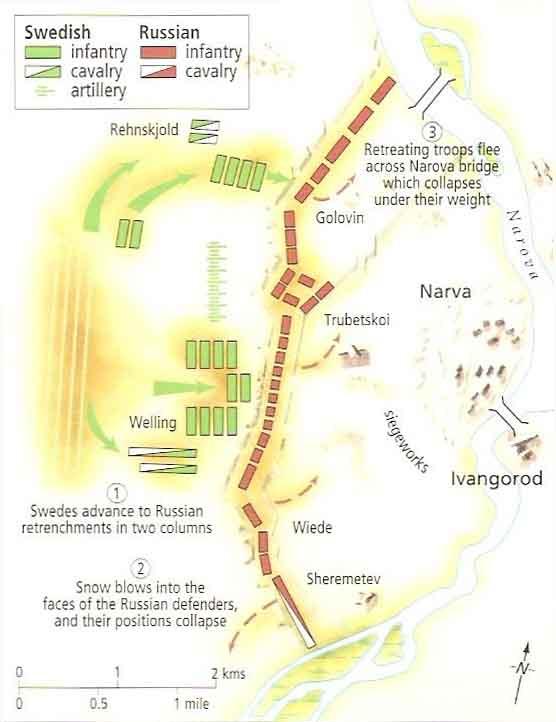

At two in the afternoon, during a snowstorm,

he began his attack on the Russian fortified camp. The Russians had around

40,000 men, but they were poorly trained, in poor shape physically and

lacking self-confidence. By nightfall, Charles and his army had defeated

Peter's army, Charles losing around 2,000 men and the Russians losing between

8,000 and 10,000 killed and many taken prisoner.

Charles was advised to follow through on his victory, to take advantage of

the panic of Peter's forces and widespread discontent in Russia. Charles thought the

Russians were imbeciles and less of a threat than Augustus and his German

army. He did not want to leave a hostile German army at his rear while

pushing deep into Russia,

and he wanted to put a candidate of his choice on Poland's throne in place of

Augustus.

In July 1701, Charles pushed Augustus and his

army out of Livonia.

In May1702, Charles reached Warsaw.

On July 2, at Kliszów, he routed a combined Polish

and German force, and three weeks later he captured the fortress at Krakow. Charles thought Augustus defeated and tried to

settle with him, but Augustus refused his offers. As monarch of Poland,

Charles replaced Augustus with Stanislaus Leszczynski,

who became Stanislaus I, King of Poland. And in a treaty signed in 1705 with

Stanislaus, Charles agreed to help the Polish monarchy regain territory lost

to the Russians in 1667 and 1686.

Peter Rallies Russia Peter Rallies Russia

Peter is reported to have wept over the defeat near

Narva. He wanted to modernize his military. The

core of the most modern armies was artillery and a disciplined infantry with

rifles, which was supposed to advance while firing and then charge with fixed

bayonets. Such armies were the product of training, mathematics for the

artillery, and a more advanced economy than Russia had. Peter's army had been

more cavalry, of nobles, than it had been infantry. His officer corps had

been largely generaled by foreign mercenaries, with

nobles filling out the rest of the officer corps. Peter saw the need for

better arms, better training, and a great number of recruits.

To enlarge his army, Peter offered good pay for those who would volunteer to

join. But, unable to attract a great number of young men, he resorted to the

conscription of men from all classes. Debt slaves freed by the death of their

owner were forbidden to contract themselves to a new master and were enlisted

as soldiers and sailors. Peter created a census to keep better track of who

was available. Landlords were obliged to submit a list of those working their

lands and to supply the army with one peasant soldier for every 50 peasant

households and one cavalryman for every 100 peasant households on their

lands. Some recruits were obliged to serve in the military for life. Peter

created a regular standing army of more than 200,000, with special forces of

Cossacks and foreigners numbering more than 100,000, and he raised taxes to

pay for his military. During Peter's reign, eighty to eighty-five percent of

his revenues would go to his army and his war efforts.

Peter had no use for precise parade-ground military drilling, for fencing

practice or for the elaborate and splendid uniforms of western soldiers. He

was concerned with instilling confidence and a sense of purpose into his

army. He tried to instill nationalist pride in his army, telling them that

they were not going to fight for him but for the interests of Russia.

This he also applied to civilians for the sake of advancing Russia economically. He wished to

discourage servility to him personally, and he encouraged his subjects to

demonstrate respect for the nation by better performance in their work. He

decreed that men should no longer fall on their knees or prostrate themselves

on the ground before him. He abolished the requirement that people remove

their hats as a sign of respect when he appeared in public - a benefit on

wintry days.

Peter was also pushing on this subjects to

westernize. He had a tax on beards, and in various places rebellions arose

against him. He wanted more of the politeness that existed in the West. To

nobles he distributed a manual on propriety. He issued decrees on dress and

personal conduct for social gatherings - more in the style that existed in Germany. And

he ordered women out of their traditional seclusion.

Peter needed people with the kind of training that people were getting in the

West. He needed teachers of arithmetic and navigation. He needed artillerymen

and shipwrights. Peter set up schools to meet these needs, modeled on schools

in England.

He created an academy of science and imported professors and students from Germany. And

Peter required young noblemen to learn arithmetic and geometry if they were

to serve the state in any position of privilege or if they were to receive a

license to marry - a compulsory education away from home that young noblemen

disliked.

In 1703, Peter started to build a fort in a desolate area on marshland that

was slowly to become St. Petersburg

- named after Saint Peter. He would have preferred to build at Riga, which tended to

be freer of ice in the winter. But Riga

was still held by the Swedes. So St. Petersburg

was planned as his port on the Baltic, to supplant the port

of Archangel far to the north, which

was icebound from November to May and in other months forced ships around Norway.

In building St. Petersburg, and in building roads, dredging rivers and

building canals, Peter used forced labor. He had soldiers build factories.

People were drafted to work in factories. There, workers who displayed

laziness, drunkenness or were careless were beaten or put into prison. And

Peter and the factory managers discovered that freely hired workers were more

efficient than those who had been coerced.

His mind still on an approaching showdown with Sweden, Peter, a religious man,

melted down church bells to help replace cannon lost at Narva.

He ordered more prospecting for metals and more iron-smelting. Ships were

constructed and launched, and sailcloth was manufactured.

Peter was also contending with revolts. The increased hardship and increased

taxation imposed on Peter's subjects provoked a number of revolts, the most

important of which was in Astrakhán in 1705-06.

There, people believed rumors that Peter was a prisoner of the Swedes or dead

and that an imposter had taken his place in Russia, that Peter's reforms were part of a plot to destroy the

Christianity that they loved. They were upset over officials from Moscow who were taxing

beards and the wearing of traditional clothing and commanding the length of

women's dresses be cut above ground-level. The belief spread that the

wig-blocks in the dwellings of officials and military officers were idols and

part of the worship of the heathen god Janus. People in Astrakhán

believed a rumor that marriage for local men was to be prohibited for seven

years and that in their place local girls were to be married to foreigners

that would soon be arriving.

The people paid for their gullibility. Peter's military burned to the ground Astrakhán and other rebel towns. As an example for

others, the people of Astrakhán were massacred. And

rebel leaders were executed by beheadings or by being broken on the wheel.

Peter Defeats Sweden in the Ukraine

In August 1706, Charles XII attacked at Dresden

and Leipzig,

and Augustus was forced to surrender. Augustus renounced the throne of Poland that

he had lost four years before, and Charles turned his attention to the

Russians. Charles wanted restitution of all lands that he thought were his,

which included the area where St. Petersburg

was being built, and he wanted Russia to pay him restitution for

having gone to war against him.

In November, Peter ordered a speeded construction at St. Petersburg - the formation of two

shifts of workers, 15,000 for each shift, for the summer building season of

1707. And early in 1707, into his military he drafted clerks, sons of priests

and deacons and other non-ordained men associated with the Orthodox Church,

and he made a cavalry regiment of former secretaries.

In 1707, Charles and his army moved into Poland,

with 24,000 horses and 20,000 foot-soldiers, and there he waited for

reinforcements from Pomerania. On January 1,

1708 Charles and his army crossed the Vistula

River, and they moved in the

direction of Moscow.

In late January, the Swedes defeated a Russian force at Grodno,

captured a bridge and crossed the river Niemen.

Peter and the retreating Russians set fire to what they could, and as the

Swedes advanced across sparsely populated Lithuania, they had difficulty

finding food for themselves and adequate forage for their horses, while

Lithuanian peasants hid their stores as they had from the Russians. Until

spring, the Swedes sought quarters at various places across Lithuania, as far east at Minsk, Charles staying about twenty miles

northwest of there until early June, when the pasture grass was again green

and thick and the roads that had been mire were again dry.

In early July, Charles and his army reached a six-mile long battle line that

Peter had created on the east side of the Bibitch

River, at Holowczyn. The Swedes surprised the

Russians by crossing the river to marshland that separated the Russian line,

and the Swedes were victorious. The divided Russian forces fell back in

another retreat. Russian moral was low. Rumors were

that Charles and his army were headed for Moscow. Peter ordered

that everything be destroyed in front of the advancing Swedes: food, crops,

anything that could be useful to the Swedes. But during the hasty retreat

much was missed, and rain had made green crops difficult to burn.

The Swedes reached Mogilev on the Dnieper River four days after their victory at

Holowczyn. There they stopped to accumulate

supplies. They were around 45,000 in number - combatants and laborers - with

30,000 horses, and they wanted to accumulate supplies, including grain, that

would last at least six weeks before moving ahead. They waited also for some

of their number who had been wounded at Holowczyn

to be fit to march. And they were waiting for a supply train of several

thousand carts, accompanied by another army, from Riga.

By the end of July the wounded had recovered, but rain was delaying the local

grain harvest. The supply train and reinforcements from Riga were late in arriving. Charles and his

army survived off the land by staying on the move. It was Peter's strategy,

at this point, to wear down the Swedes by means of quick strikes and withdrawal,

and on August 31, in the morning fog at Malatitze,

Peter, using infantry for the first time, attacked two Swedish regiments. The

Swedes lost almost 300 men killed and 500 wounded. The Russians lost around

700 killed and 2000 wounded. After two hours of fighting the Russians

withdrew, leaving the Swedes with the impression that the Russians had

improved militarily.

In pulling back, Peter kept his scorched earth policy. Anyone who gave or

sold food to the enemy, or knew of such an act and said nothing, was to be

hanged, and those villages from which food was to be given were to be burned

to the ground. The Swedes reached Tatarsk, but the

countryside between them and Smolensk

was barren of whatever they needed to survive. By mid-September the supply train

and army from Riga

had not yet arrived. Charles and his men and horses faced starvation. Facing

the coming of winter and devastation along the road to Moscow,

Charles decided to turn south, into the Ukraine, into terrain that was

more densely populated and that held supplies of food and fodder. There also

he hoped to team up with the ruler of the Ukraine's

Left Bank, Ivan

Mazepa, a Cossack who had been appointed by Peter

but who believed that Charles would win against Peter and was secretly

negotiating an alliance with Charles.

Casualty figures by Frans G. Bengtsson, The Sword

Does not Jest: the Heroic Life of King Charles XII of Sweden, p. 311.

On September 28, Peter's army found the Swedish baggage train from Riga. A battle ensued,

at Lesnaia, about thirty miles southeast of Mogilev. Each side had

about 12,000 men. After eight hours of fighting the Russians lost 1,111

killed and 2,856 wounded. NOTE Swedish losses were at least as heavy. The

army accompanying the baggage train scattered. The Russian captures some of

the supplies, and about a thousand of the Swedes headed back in the direction

of Riga. The

commander of the baggage train, General Lewenhaupt,

ordered what remained of the supplies burned, believing that he was no longer

able to protect it from the Russians.

Lewenhaupt and his men finally found Charles' army,

and they joined Charles in heading for Katurin, Mazepa's capital, where Charles hoped to be supplied with

gunpowder and other necessities. Winter was setting in. Mazepa,

fearing retribution from Peter, fled from Katurin

with a part of his army. The Russians arrived at Katurin

in early November and destroyed the town, leaving nothing for the Swedes. The

town's inhabitants were massacred, except for boys who were carried off by

the Russians and about a thousand Cossack warriors who managed to fight their

way through the Russian line.

Mazepa joined himself and the modest remnant of his

Cossack army, with Charles and his army. And Charles quartered for the winter

at Romny, where his famished and exhausted men

found an abundance of supplies, including hay, oats, cattle, sheep, and wine.

It was an exceptionally cold winter. The Baltic Sea was frozen over and the

canals of Venice

were covered with ice. In the Ukraine

birds in flight fell dead. But Charles believed that he had to keep up his

offensive against the Russians, to keep the Russians from rebuilding their

forces. His strategy was to poke at the Russians, keep them off balance and

to lure them into the showdown that they had heretofore avoided. Charles

wanted another battle like the one at Narva. He was

confident that again his smaller army of Swedes could defeat a larger Russian

army. And this time he wanted to destroy the army, which he believed would

end the war in his favor.

Winter fighting took a toll on the Swedes, Charles losing perhaps more than

1,000 men in January and more men in another skirmish in February. Many of

his troops suffered from frostbite. By spring the army was at about 24 or 25

thousand. Local grain supplies and cattle were sufficient, but gunpowder was

low, some of it having been damaged by the wet weather in February.

In April, the Swedes lost 400 men in another battle. That month, Charles was

reconnoitering the Russian fortress at Poltava

(about a hundred miles southeast of Romny). There

the Russians had about 30 cannon and 4,000 troops. In mid-May, Charles laid

siege to the fortress, hoping this would bring the main Russian force,

against which he planned to spring a trap.

Meanwhile, competition was taking place for the friendship of the Khan of the

Tatars in the Crimea. The Swedes were trying

to bring the Khan into the war on their side, while Russians were

misinforming the Tatars about the Swedes and distributing gold coin to

influential Tatars. The Russians told the Tatars that the Swedes were about

to conclude a peace with them, and the Tatars chose to stay out of the

fighting.

Peter moved his army - around 45,000 men - on the Vorskla River,

opposite the fortress at Poltava.

In a minor skirmish on June 28, Charles received a bullet wound in his foot.

Many of the Swedes had come to believe that God had been shielding their

anointed king, and dismay spread among them. The days were now unusually hot.

Wounds, including that of the king's, were not healing well. Charles barely

survived.

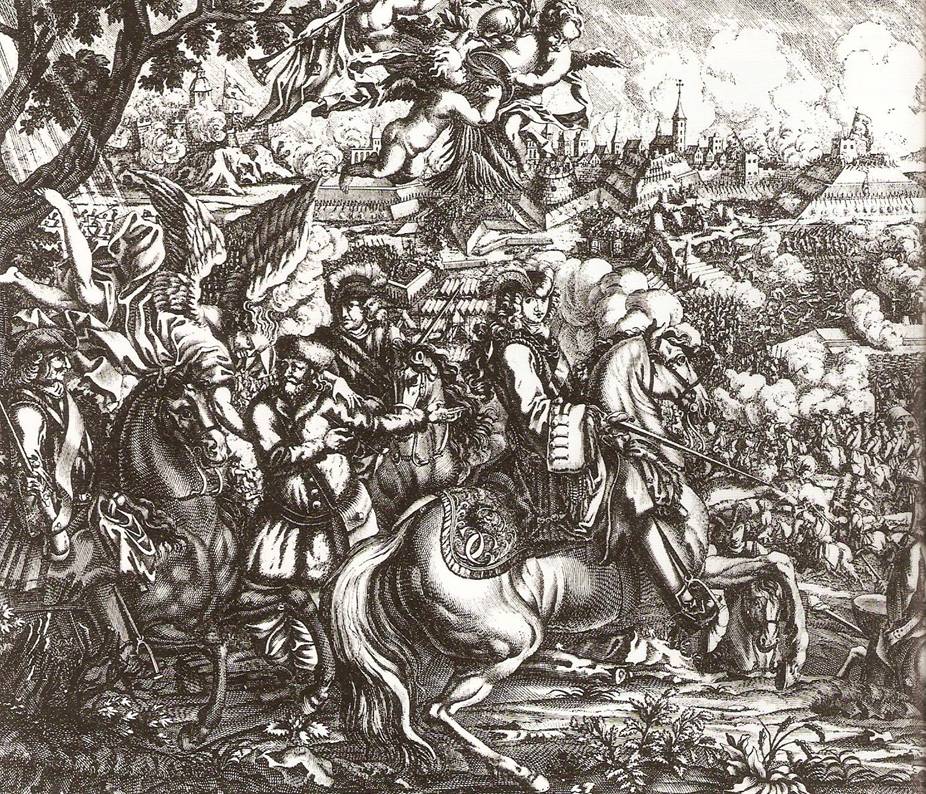

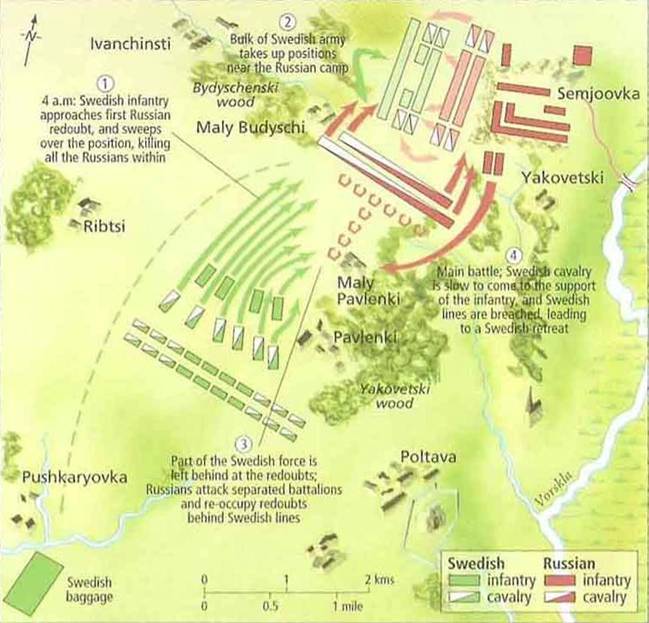

The showdown came on July 8, without the trap that Charles had been hoping

for. The Swedes were eager for battle and moved with élan against the Russian

entrenchment. Not yet recovered, Charles was carried about on a litter. In

two hours of battle, the Russians overwhelmed the Swedes and Mazepa's Cossacks.

Russian artillery cut the Swedes down, and

the poor quality of the gunpowder used by the Swedes caused their shots to

fall short. The Swedes and Mezepa's troops fled. A

remnant of the Swedish army - 14,299 men and 34 cannon - surrendered at Perevolchna. The Swedes had lost 6,901 dead and wounded,

and 2,760 captured. The Russians had lost 1,345 dead and 3,290 wounded. NOTE Charles, his aides, a few hundred cavalry, Mazepa and around 1500 of his Cossack warriors escaped

across the border into Ottoman territory - to Ochakov.

And with Mazepa went hope for Ukrainian

independence.

Casualty figures by

Lindsey Hughes, Russia

in the Age of Peter the Great, p. 39.

Sweden loses the Great

Northern War

Russians described the victory at Poltava as a divine

miracle. Europeans outside of Russia

were also astounded, and they viewed the Russian victory with foreboding. Russia,

they thought, would now be a formidable power in European affairs.

Seeing Sweden as having

been weakened, Augustus of Saxony and Frederick IV of Denmark renewed their alliance with Russia.

A prince of the Hohenzollern family, Frederick of Brandenburg-Prussia, agreed

with Russia to bar Swedish

troops in Pomerania from access to Poland

in exchange for gaining the town of Elbing

(Elblag).

In November 1709, Frederick IV of Denmark invaded Sweden with 16,000 troops,

overrunning the towns of Malmö and Lund, and in

February they were driven back to Denmark, Sweden's successful defense

impressing the rest of Europe.

Charles XII remained with the Ottomans, at Bender, about a hundred miles west

of Okyakov. He urged the Ottomans to war against

the Russians, and Europe watched with anticipation of another such war, with Sweden on the

side of the Ottomans. The war between Russia began again, with Peter

hoping to win the Christians in Ottoman territory to his side.

The Russians, meanwhile, had seized Vyborg, Riga, and Revel and had pushed into Finland. With

Charles II defeated in East Europe, King Stanislaus I was repudiated in

Poland, and with help from Peter, Augustus again assumed the title King of

Poland. Stanislaus escaped to Swedish Pomerania, and from there he went to Weissenbourg, becoming master of the principality of Zweibrücken - his daughter, Mary, to marry King Louis XV

of France.

Peter's hopes regarding his war with the Ottomans had failed. With the

Peter's armies spread thin, the Ottomans had the advantage over him. In 1711,

numerically superior Ottoman forces surrounded Peter and an army short of

ammunition and supplies, by the Pruth

River, deep into Moldavia. But

the Ottomans did not share Charles' passion for crushing the Russians, and

they allowed the Russians to withdraw.

In 1712, the Danes took the Duchy of Bremen from the Swedes, and they took

Charles's spot of land in Holstein. In 1713,

Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia took Stettin.

And Georg Ludwig, the Elector of Hanover - soon to be King George I of England - joined the coalition against Sweden.

Frederick William succeeded his father, Frederick, in February, 1713.

Peter and the Ottomans signed a peace treaty. Peter returned Azov and other

territory he had gained from the Ottoman Empire in 1700, and he agreed to

allow Charles safe passage from Ottoman territory back to Sweden. And

the Ottomans recognized Augustus as Poland's rightful king.

In late 1714, Charles and around 1500 troops made their way back to Sweden by

way of Vienna, and with help from the Habsburg monarchy in Vienna, which had

begun to look with favor upon Charles and Sweden as a brake on Germans to

their north. The Swedes journeyed through Bavaria

and western Germany

as incognito as possible, for the sake of safety.

Charles still saw the area around St. Petersburg

as his territory, and Peter now considered St. Petersburg

as Russia's

capital. In 1714, Peter had begun ordering people to move there. Nobles were

obliged to build homes in St.

Petersburg and to live in them most of the year. The

more serfs that a noble had the bigger his home had to be. Merchants and

artisans were also ordered to move to St. Petersburg

and to build on the side of the Neva

River opposite the

nobles. The new residents of St.

Petersburg were ordered to pay for the building of

avenues, parks, canals, embankments, bridges and other projects. And huge

government buildings, designed by foreign architects, were constructed.

Charles Continues the War

From Ottoman territory, Charles went to Swedish Pomerania - to his fortress

at Stralsund.

With his arrival back on Swedish territory, after a fourteen-year absence,

the people of Sweden

momentarily forgot the unusual hardships of the recent years and erupted with

joy. They foresaw their king as now about to smash those who had dared to

move against Swedish territory.

It was a powerful coalition that Charles faced: Peter of Russia, Frederick of

Denmark, Augustus of Saxony and Poland,

Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia, and George of Hanover and England.

Like some rulers in the twentieth century, Charles was undeterred in facing a

great coalition. Having at that point lost the most important of contests -

the diplomacy war - he was not about to ask for mercy and sue for peace.

Instead, he entertained the notion that he could hurt his adversaries enough

that they would want to make peace and return to him all of his empire - or

at least an empire equal in size to that which he had before the war.

By late June, Prussian and Danish troops had encircled Wismar by land. And on

the sea, the Danish and British navies were cooperating, and the Danes were

blockading Wismar.

Facing numerically superior forces in Pomerania, Charles withdrew his troops

to his fortress at Stralsund.

In November a flotilla of 640 transport ships landed Danish and Prussian

troops that overran the fortress at Stralsund.

Charles escaped to the southern tip of Sweden. Swedish troops at Stralsund were made

prisoners of war, marching into captivity with banners flying and music

playing, expecting to be released in a few months following payment for their

keep to Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia. Civilian officials at Stralsund were released

immediately. Mercenaries who had been fighting on the side of the Swedes were

made prisoners of war, and most of them, as expected, chose to do service for

their captors.

Charles was now concerned about his enemies invading Sweden proper. He decided that he

could discourage any such invasion by attacking Norway. An invasion of Sweden, he

reasoned, required the Danes, and by attacking Norway - then property of his

cousin, the Danish king, Fredrick IV - he could persuade his cousin to

withdraw from the coalition against him, by crushing the Danish army in a

major engagement. Charles also believed that invading Norway would compel the British to keep some

of their navy along their coast opposite Norway,

weakening help from the British fleet in an invasion of Sweden.

Charles' Norwegian campaign began in February, 1716. Norway's government fled the capital city,

Christiania (Oslo).

The Swedes occupied Christiania in March.

Norwegians failed to cooperate with the Swedes, eschewing their traditional

hospitality to foreigners. The Swedes in Christiania

were low on supplies. Winter was delaying logistic support, and Denmark's navy commanded the approach to

Christiania, forcing Charles to abandon Christiania

in April, before Danish reinforcements landed at Fredrikshald.

Charles and his troops made their headquarters near Fredrikshald

instead, where they waited for Swedish ships to bring them supplies. The

Swedes and Danes fought for control of the waters around Fredrikshald.

The Swedish navy won in May, but in late June the Swedes lost both on sea and

on land. Charles and his troops returned to Sweden

without his crushing victory over Denmark's

army, but his invasion of Norway

did disturb the plans for an invasion of Sweden by the coalition against

him.

Wismar had finally surrendered to the

coalition's forces, but Peter was upset over the refusal of the Danes, Prussians

and Saxons to permit Russian participation in the occupation of Wismar. The use of

Russian troops was planned for an invasion of Sweden that year. During the

summer, the coalition was slow in getting a navy together large enough for a

landing in Sweden,

including the wait on Danish ships that had been involved in actions against

the Swedes in Norway.

The attack by Charles, moreover, had impressed coalition members - especially

Peter. They had thought in 1715 that Sweden had been all but defeated.

They had been aware of war-weariness in Sweden

and Sweden's

diminished supply of money. Now, in 1716, they were impressed by the fighting

capability that remained with Charles. Peter reconnoitered Sweden's coast, concluding that Sweden's

defenses were strong. He was disappointed that Sweden's navy had not been

defeated, and in mid-September he pulled out of the planned invasion,

claiming that it was too late in the season and suggesting postponement of

the invasion until the following year. This did not suit Fredrick of Denmark,

who had commandeered the ships of Danish merchants and believed that he could

not hold them for two years running. The decision to invade was postponed,

and there would be no invasion of Sweden.

Charles'

Final Failure

Charles made his headquarters at Lund,

where he hoped for further division of the coalition against him. He began to

talk peace with members of the coalition, but it was only to gain time to

prepare for a military offensive. He saw no hope no hope of making peace with

George of England or Peter of Russia, whom he saw as his two main enemies. He

wanted a major victory so that he could bargain from strength.

At Lund, he

took an interest in theological disputes - his praise of Muslim virtues,

which he had learned while with the Ottomans, disturbing some. Charles began

each day with prayer and some reading from the Bible. His chaplain claimed

that it was his duty to bring an end to the war as soon as possible, but

Charles acquired no inspiration to bargain seriously for an end to the war,

including a willingness to give up territory already lost. Charles was not

about to give up on empire.

Meanwhile, some Swedes were being influenced by the new belief in

constitutional government that had developed in the Netherlands and Britain.

After the death of Louis XIV of France in 1715 even the French

were experimenting with constitutionalism. In Sweden, opposition to the

absolutism of Charles was perhaps small, but it was growing. And opposition

was growing also to the continuation of war, spurred by Charles' decree of

raised taxes as the public's contribution to the war effort - a tax to be

paid by nobles, high-ranking officers in the military and high ranking

members of the bureaucracy.

Charles was allowed to build his strength through 1717 and much of 1718.

Rather than let the war fade, he had plans for an offensive for October,

1718. On the 16th of October he moved again toward Fredrikshald,

aiming at the nearby frontier fortress of Fredriksten.

The going was slow, and, toward the end of November, Charles and his army

were encamped in front of the fortress. Charles was interested in the new

line that was being dug fifty yards closer to the fort, and around eight in

the evening, on November 30, Charles raised himself above the crest of his

rampart to have a look. Flares were burning on the fortress, and lightbombs were giving some illumination. Scattered shots

were being fired and one struck Charles on the left side of his head as he

was looking to the right. He fell off of the ladder, dead at the age of

thirty-six.

On assassination and

the death of Charles see R.M. Hatton, Charles XII of Sweden, 501-509.

It was believed by some that Charles had been immune to ordinary bullets and

that the missile that had killed him had been a silver or brass button. It

was rumored too that he had been assassinated and that Charles' younger

sister, Ulrica Leonora, who appeared too ready to

succeed Charles, had been part of a conspiracy against him. Ulrica Leonora had been devoted to Charles and was

observed horrified and hurt by his death. But the assassination theory lived

on and controversy was to rage into the twentieth century over whether

Charles had been assassinated.

A Constitution and

Peacetime Prosperity for Sweden.

Since late in the 1200s, a Council had existed in association with the

authority of the king, and with the death of Charles in late 1718, the

Council exercised authority concerning who would replace Charles. Charles had

never married, and his closest surviving sibling was Ulrica

Leonora. The Council selected her as queen on condition that she renounce all claims to absolute power. She agreed, and the

following year she abdicated in favor of her husband, Frederik

of Hesse, on condition that they agree to leave the

creation of a new constitution to others. They agreed. Frederik

became Fredrik I, King of Sweden, and Ulrica

Leonora was queen. A peaceful political revolution had taken place,

influenced by the development of constitutionalism elsewhere in Europe.

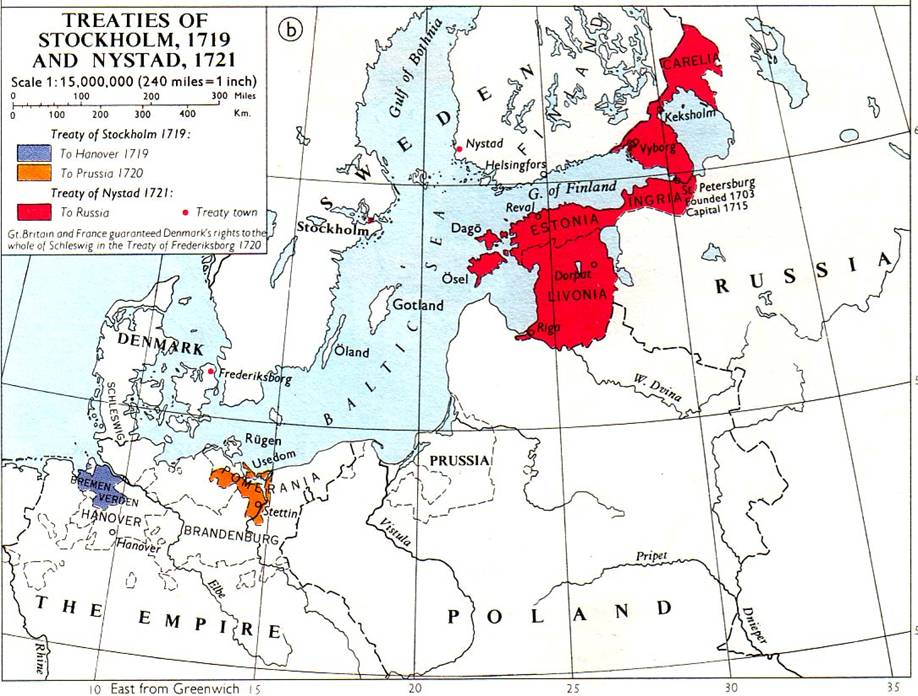

The Swedes began doing what Charles could have done in 1717. Sweden made

peace. Sweden

made peace with Augustus, recognizing him as King of Poland. Sweden made peace with Hanover, agreeing to give up the Dutchy of Bremen and Verden. In

1720 Sweden

settled with Fredrick William of Brandenburg-Prussia. It recognized its loss

in Pomerania. It made peace with Denmark. And,

in 1721, it made peace with Russia,

recognizing Russia's hold

on territory it had conquered, including Ingria, Estonia,

Livonia, Vyborg

(Viipuri), Kexholm (Piorzersk) and part of Karelia.

Sweden was no longer the

dominant power over the Baltic Sea. That now

belonged to Russia.

The

Constitution and Prosperity

The writers of Sweden's

new constitution were influenced by what had taken place among the Dutch and

English, including the writings of John Locke. It was Sweden's

first full and precisely written constitution, and it gave the Swedish people

what they, and historians later, would call an "Age of Liberty."

Basically the Constitution provided for parliamentary rule. Parliament was to

meet at least every third year, and parliament alone was to control state

finances and legislation. When parliament was not in session, the

sixteen-member Council ruled with the king, who had two votes on most issues

- the duty of the Council and king being to run the government and to implement

the decisions of parliament.

Parliament consisted of four

"estates" - one estate being that of nobles, another estate

represented towns, another the clergy, and the fourth estate represented

farmers. The estate of the nobles was largest, having around 1,000

representatives in parliament. Representatives from the towns numbered

between 80 and 90. The clergy had 50 members, and the farmers around 150 -

one from each rural district. To pass into law, a proposal needed the

approval of at least three of the four estates. Special committees handled

various issues and were allowed to intervene in the administration of the

judiciary. Members of the farmer estate were excluded from the committee on

foreign affairs but included on the issue of taxation.

Sweden was more of a rural society than Great Britain or the United Provinces.

It had less of a middleclass or bourgeoisie than the British or the Dutch.

Ninety percent of the Swedish population still lived by farming and raising

cattle. But Sweden's rural

population, with their small farms, was uncommonly independent compared to much of the rest of Europe.

Serfdom did not exist in Sweden,

as it did extensively in Russia,

Poland, the

Balkans and to a lesser extent in Denmark,

Spain and France.

The loss of overseas provinces had reduced

the king's revenues by more than half, and the nobility had lost their reward

of lands abroad. But with loans from the English and the French, and, more

importantly, with peace, hard work and good harvests, the Swedes began to recover

their old standard of living. They had a baby boom. Trade returned. The

Swedes welcomed the imported goods which they had long been deprived. And

prosperity and inflation made the tax burden lighter.

The government encouraged new opportunities

for the poor, with exemption from taxes and other privileges for colonizing

territory in the far north. The move of settlers there came into conflict

with Lapps of the area, the Lapps trying to hold on to their use of fishing

waters and pastures for their reindeers. And Sweden's government supported the

settlers, forcing the Lapps to withdraw from contested areas.

Parliament, meanwhile, had done away with the

distinction between high and low aristocracy, and it left the nobility

exempted from land taxes and with the exclusive right to hold high office in

civil service. But these laws were impractical and failing, as commoners with

talent were being appointed to high office and as a few farmers were gaining

in wealth and acquiring their own tax exempt farming estates.

Sweden's industrial sector

remained small, but in 1731 new factories were founded with support

from the state, especially in textiles, which, in urban areas such as Norrköping and Stockholm,

began employing between 13,000 and 14,000 people. By the middle of the

century there would be 360 ironworks in the country, producing 47,000 tons of

wrought-iron goods annually.

In foreign policy, the government allowed

foreign vessels bring into Sweden

only goods originating in their own country, the Swedes aiming to advance

their own merchant marine. This annoyed the British. Nevertheless, Sweden was able to maintain a new alliance

with Britain, as it did

with France

and Brandenburg-Prussia.

Nostalgia for Glory.

All of these successes did not totally

obliterate a glorification of Sweden's

past. The connection between impoverishment and war was not firmly

established. The old idea that wars should pay for themselves in the form of

reward to the victors and that victory was natural for one's own side, was still alive in Sweden. Political parties had

developed in Sweden

that ran across the political boundaries called Estates. One of the parties

was called the Hats (Hattar in Swedish). It

consisted largely of aristocrats and people nostalgic for what they believed

were glories connected with militarism. The Hats were for improving the

nation's armed forces. They had cultural links with and received money from

the French. They favored revenge against Russia and the acquisition of

lost territories. Allied with them was Sweden's numerically small but

wealthy bourgeoisie, the Hats favoring industrial development and economic

investments. Many towns chose to be represented by members of the Hat party,

and the Hats favored more control over the labor guilds, town privileges and

projectionist policies.

Opposite the Hats were the Caps, who

represented the interests of small farmers. Small farmers tended to be for

peace and tended to side with the English, from which they also received

money. The Caps had been dominant before 1738 and had been careful not to

provoke Russia.

In 1738, the Caps lost to the Hats, who gained a majority in Parliament. The

Hats forced Sweden's

elder statesman, Arvid Horn, to resign from his

post as Lord President of the Council. They made Hat government made treaties

with France

in order to obtain subsidies and support against the Russians. A new war

erupted in 1740 - the War of Austrian Succession - which gave the Hats an

opportunity to join sides and war for revenge against Russia.

Bibliography

Charles of Sweden, by R M Hatton, 1968

The Sword Does

not Jest: the Heroic Life of King Charles XII of Sweden, by Frans G Bengtsson

Russsia in the Age of

Peter the Great, by Lindsey

Hughes

Swedish

History, by Jörgen

Weibull, Svenska Institutet, 1997

Originally

published at http://www.fsmitha.com

BACK TO THE BALTIC STATES

BACK TO FINLAND, KARELIA & INGRIA

|