|

|

The Empire of Poland and the

Baltic Nations

By Kathy

McDonough

Maps: Andersen, A.,

The New Cambridge Modern History Atlas, 1970

Putzgers, F.W., Historischer Schul-Atlas, Bielefeld,

1929

|

Introduction

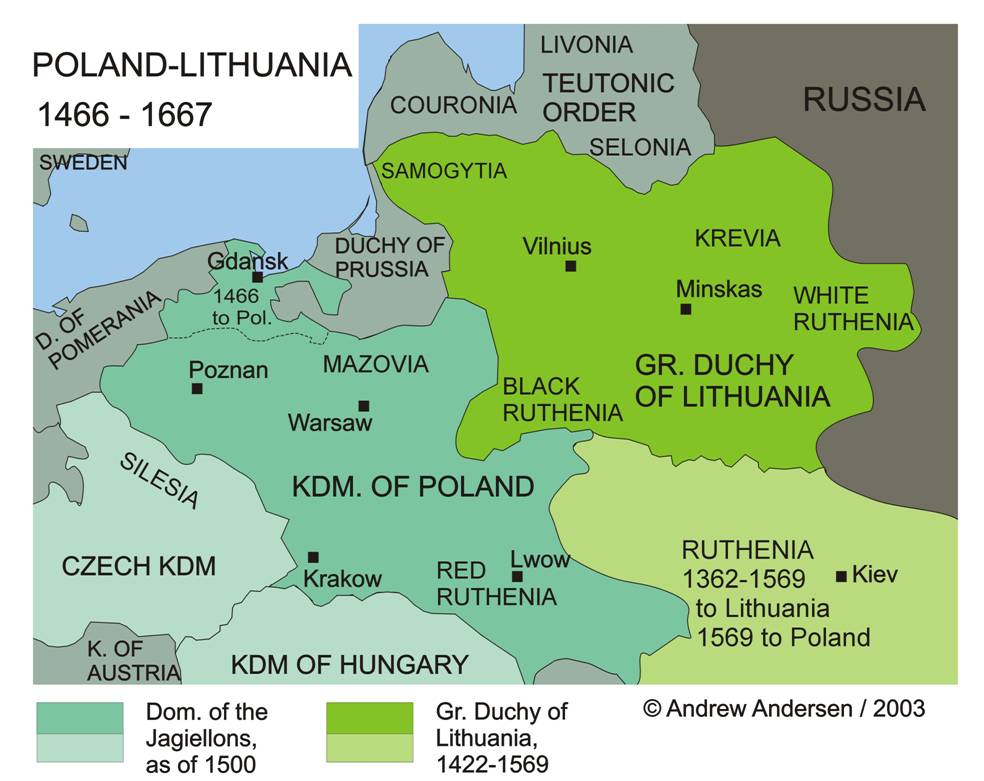

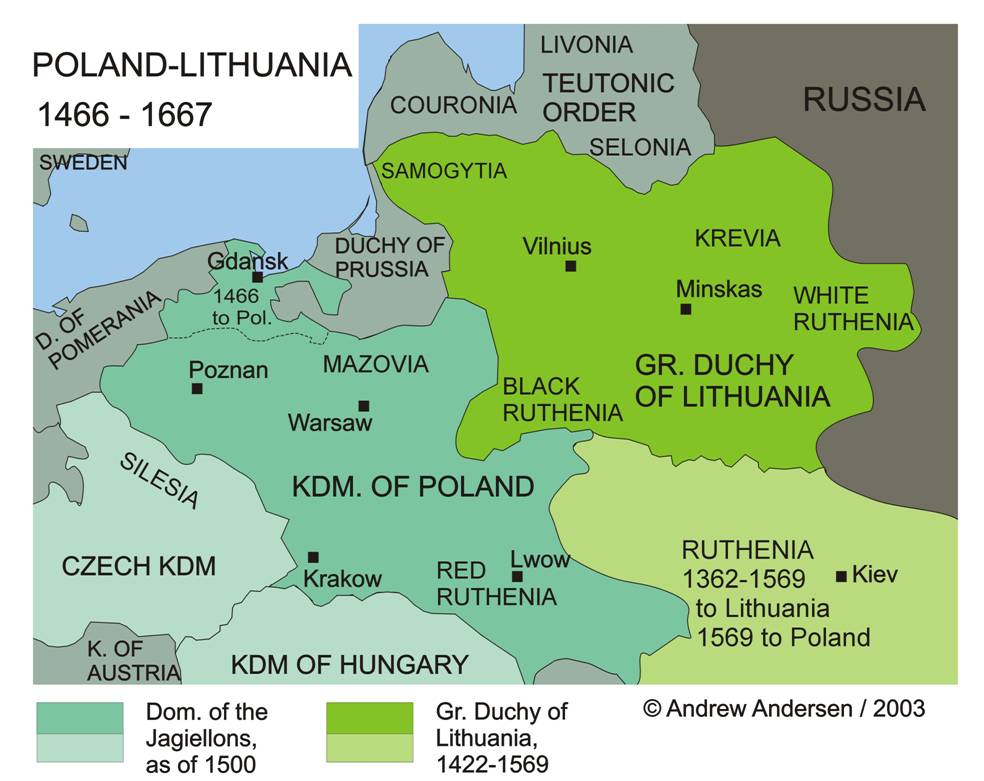

The Empire of Poland, at times, has reached from the

Baltic Sea to the Black Sea; its territory

being important for its position along trade routes in the Baltic Region. Poland’s closest Baltic neighbor (Lithuania), has been a valued ally in the

battle for freedom from foreign rule of Sweden,

Germany, Russia, Prussia

and Austria

since 1386. Although the Polish Empire was continually invaded, beginning in

1605, technology and education in Poland remained strong and

progressive for the time and "polonization"

of the Lithuanian nobility was evident. The example Poland set through her liberal government and

the uprisings of 1830 and 1863 helped Lithuania in the revolution of

1905. In the 20th century, events from the past regarding the city

of Vilnius have put strain on Polish and Lithuanian relations, though their

cooperation is necessary to the harmony of the Baltic Region.

Early Connections with Lithuania and Dynastic Rule

Poland,

like Lithuania,

has a history based on trade. In Poland,

the city of Danzig was an important route for

trade with Amsterdam; Lithuanian cities and

rivers were on important trade routes into Russia.

In Poland,

dynastic rule began in 962. The Piast Dynasty

lasted from 962 – 1370. During this time period, Poland was converted to

Christianity and wars against the Holy Roman Emperor took place under the

leadership of Boleslaw I. These wars were successful in extending Poland’s boundaries beyond the Carpathian Mountains (Encarta). In addition to expanded

territory, Wladyslaw I brought victory over the

Teutonic Knights bringing prosperity to Poland. His son Kazimierz III was noted for his role in administrative,

judicial, and legislative reforms which began Poland’s notoriety in progressive

governmental policies.

In 1325, the Grand Duke Gediminas’

daughter (Aldona) married Casimir

the Great of Poland, furthering the links between Poland

and Lithuania.

The formal link between Poland

and Lithuania

began with the Union of Krewo in 1385. In this

agreement, Jogaila (the Grand Duke of Lithuania)

agreed to baptize Lithuania,

free Polish prisoners of war and recover lands that had been taken from Poland – in sum, it

would unite Poland and Lithuania.

From this agreement emerges the Jagiellon Dynasty.

The Jagiellon Dynasty

(1386 – 1572) was established by the marriage of Jogaila

and the Queen of Poland (Jadwiga) in 1386. With Lithuania

and Poland

united, they were able to defeat the Teutonic Knights at the battle of Grunwald in 1410 under the leadership of Lithuanian Grand

Duke Vytautas.

In 1569, the Lublin Union united Poland and Lithuania

as the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth installed an

"interstate federal union based on common institution" (Lerski 622). This meant that kings were elected jointly,

but the legal systems and administrations remained separate. The states acted

as a single entity in external affairs and this helped with the gradual

"polonization" of the Lithuanian people.

According to Suziedelis,

Catholicism was the "major ‘polonizing’ force

in Lithuania"

(223). "Polonization" was characterized

by the increase of the Polish language in business and religious affairs,

making the nobility a large group speaking mostly Polish and the peasantry a

group speaking mostly Lithuanian. This meant that the nobility in Lithuania

identified with the Polish culture. Almost all official documents were now

being written in Polish. "Polonization"

occurred mainly with the Lithuanian, Rutherian and

East Latvian nobility, but numerous privileges for the gentry of Poland and Lithuania ensued. The increasing

cultural domination of the Poles, both numerically and culturally led to

animosity between the two states. Vytautas was

noted for trying to threaten the Polish–Lithuanian union by supporting an

independent Lithuanian Kingdom (Harrison).

In the future conflicts over Vilnius,

"polonization" was a major cause of

resentment between the two countries (Suziedelis).

The War of Inflanty

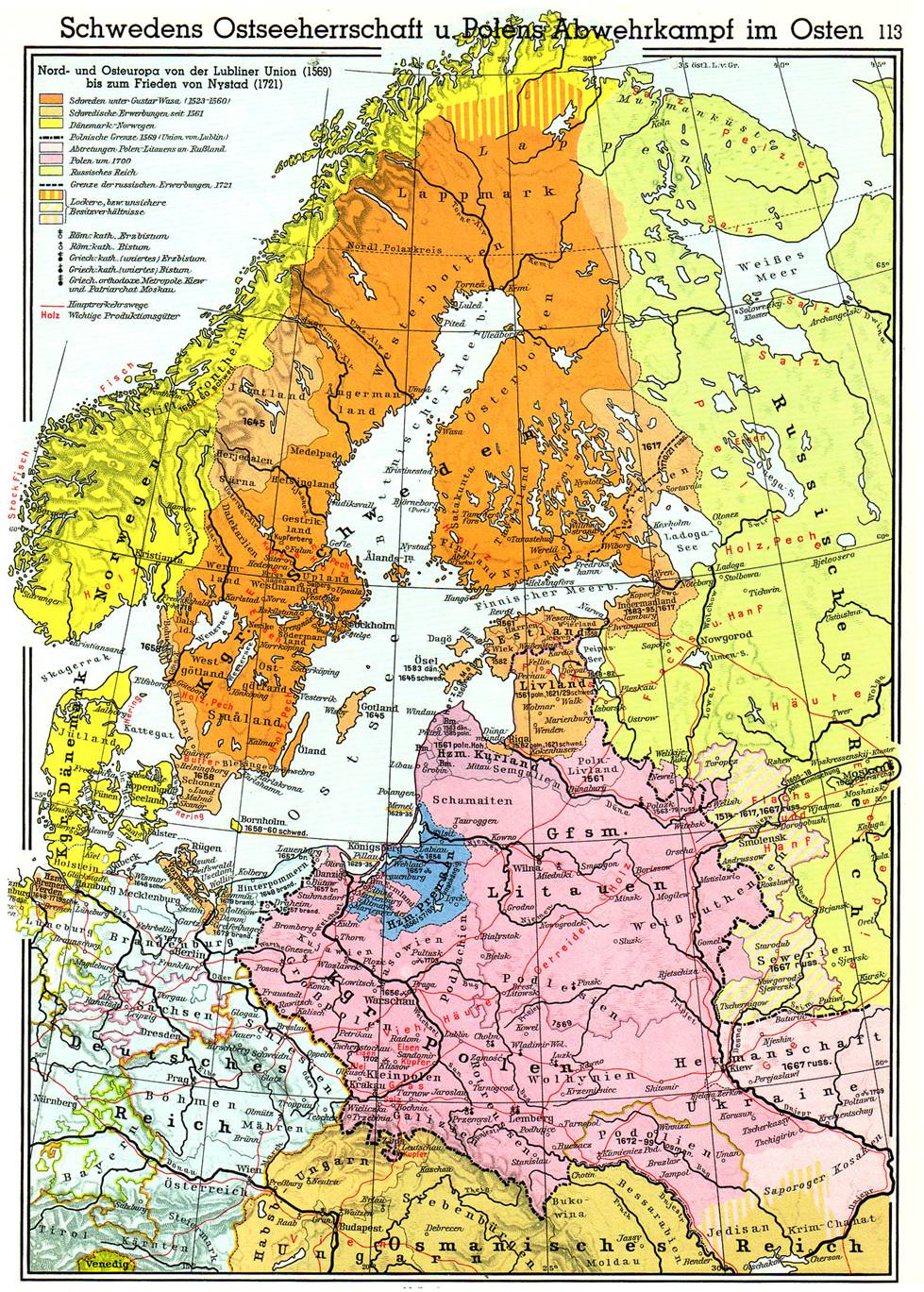

1558 brought the War of Inflanty

or the Livonian War.

This was the invasion of Russian and Tatar troops into Livonia. The king Zygmunt

August of Poland is noted

for his reluctance in sending troops immediately to aid Livonia. He is thought to have been

unprepared for the invasion by forces of Muscovy

in 1559. Despite his reluctance, in 1561 the Livonian city of Riga came under Polish

rule. In 1561, the city of Tallinn also swore

allegiance to Erik XIV (the Swedish King) but the southern regions of Livonia were taken by

the King of Poland. The second part of the Livonian War came in the 1580’s

where Sweden and Poland fought for hegemony in Livonia

and in 1582 they forced Ivan (the terrible) to surrender to Poland all areas under Russian control in Livonia. After the war,

Poland controlled

territory up to what is central Estonia today. The northern

regions were soon lost to Sweden,

but Poland remained in

control of the southern Baltic, including much of modern day Lithuania and Latvia,

for almost 200 years until the partitions of Poland in 1772 and 1795 (Kirby).

Click

on the map for bigger image

The Duchy

of Courland, established after the Livonian War as a vassal state of the Polish-Lithaunian Commonwealth, was valuable for trade because of its

location on the Baltic Sea. The most famous

leader in Courland was Duke James Kettler, who helped the area form administrative and

judicial statutes by means of its constitution the "Formula Regiminis." This constitution allowed the duke to be

an independent leader, not under the King of Poland. Under Duke James Kettler, Courland

flourished in the trade of naval stores and developed the largest maritime

fleet in the world (Lerski).

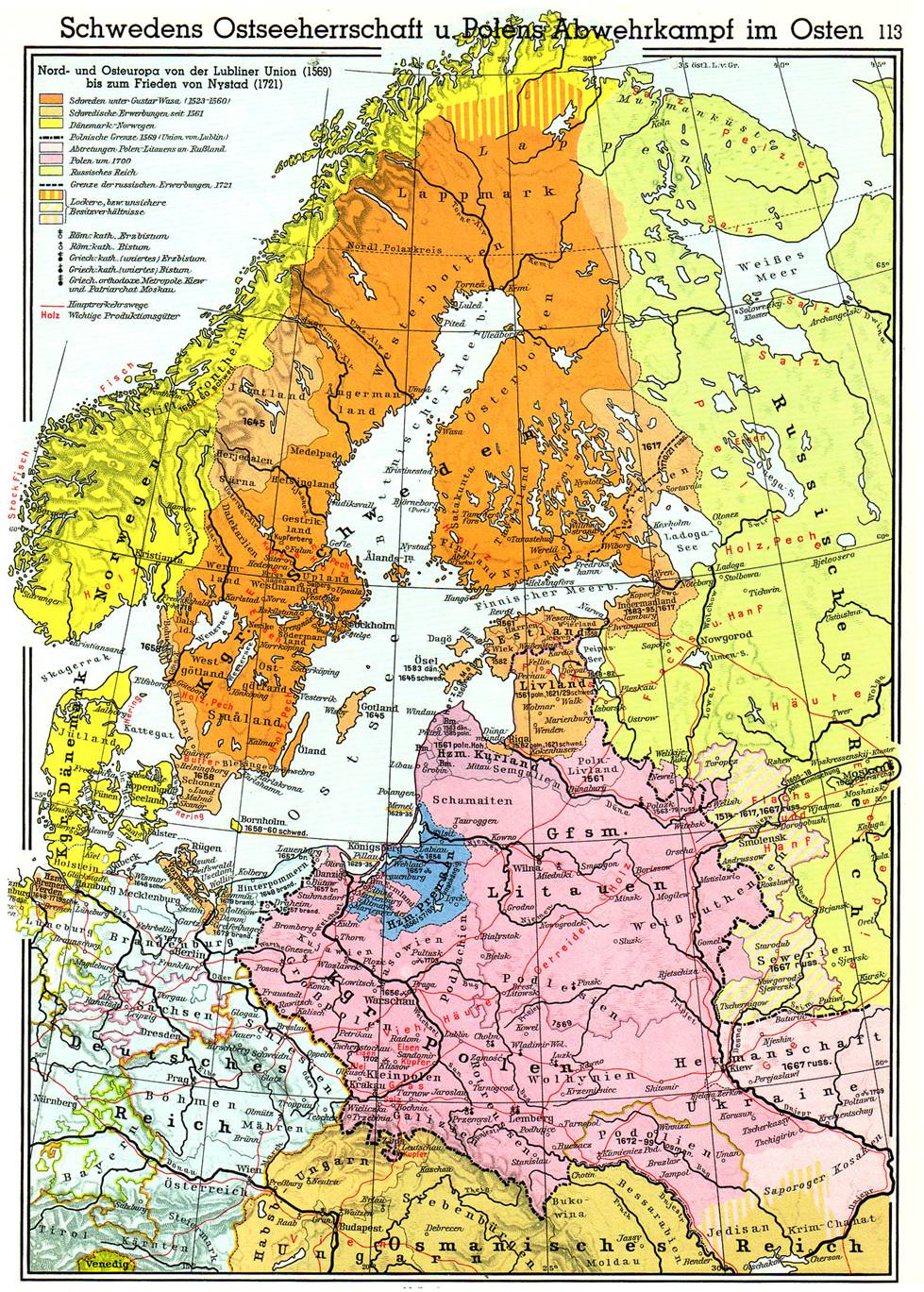

War with Sweden

In 1600 - 1621, Sweden

invaded Poland in an attempt to make the Baltic Sea

into their "internal lake" (Lerski 107). Sweden took control of the regions north of

the Daugava

River, including the city of Riga. Courland served

as a battleground in Poland’s

war with Sweden.

The Great Northern War

In 1700, the Great Northern War broke

out. This attempt to rid northern Europe of Swedes was led by Russia and Denmark. Poland, fighting along with Lithuania, became involved in the Great

Northern War by the alliance made with Russia in 1700 by Augustus II

(King of Poland). They invaded Livonia but the

Swedes defeated both Russia

and the Commonwealth troops. The city of Vilnius

was captured by Sweden

in 1702. Peter the Great finally defeated Sweden

in 1709 and Russia

remained in control of the Grand Duchy for many years following.

A plague epidemic followed this war and wiped out

almost 1/3 of the population in this region. When the war ended in 1721 with

the Treaty of Nystadt, the countryside was

demolished but Swedish influence had been pushed out of Livonia and replaced by Russian dominance (Suziedelis).

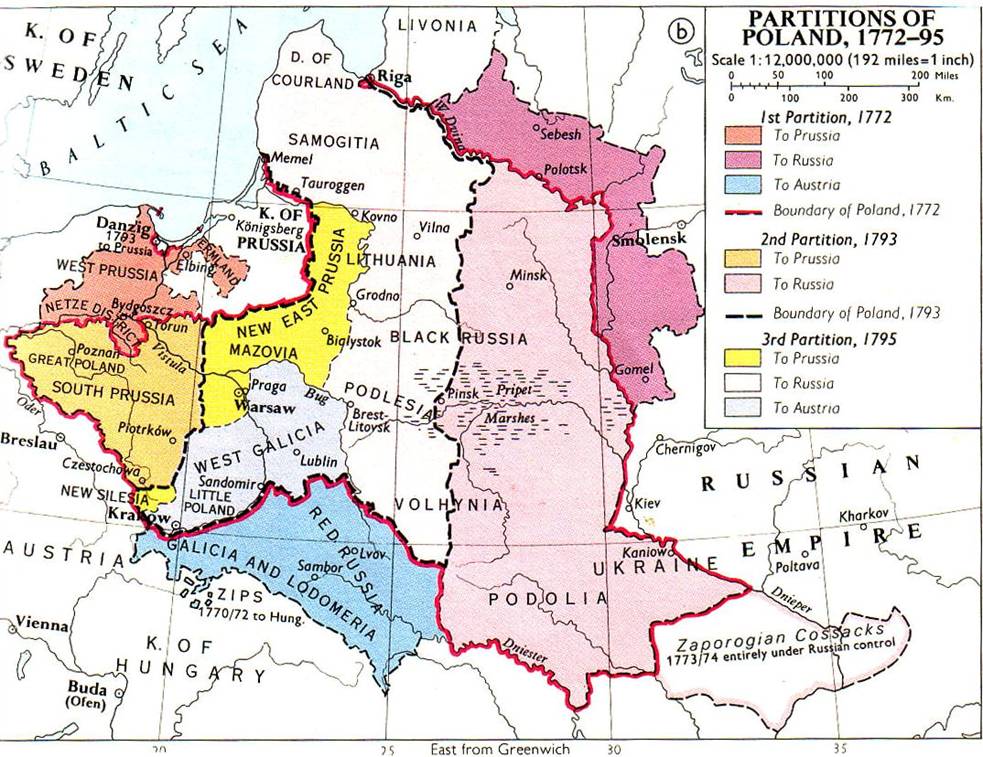

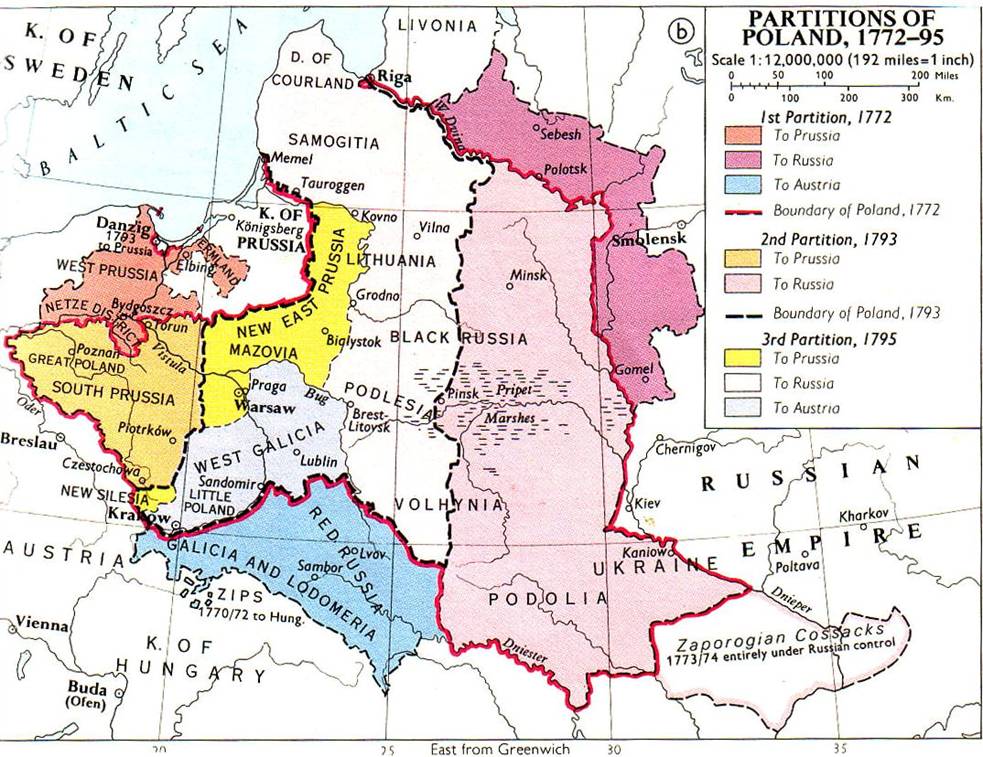

Poland

Under Foreign Rule

When the neighboring countries of Russia, Prussia

and Austria formed the

"Alliance

of the Three Black Eagles" in 1732, annexation was soon to follow. The

first annexation occurred in 1772, the second in 1793 and the third in 1795

which eliminated Poland

entirely as an empire (Kasprzyk).

While Poland was still an independent

country, it accepted the Constitution of 1791. This Constitution was the

second in the world after the United

States (Lerski

82). It emphasized the idea of "people’s sovereignty," separated

powers of the executive, legislative and judiciary branches and offered

protection to the peasants by law. The liberal ideas of both the constitution

and the Polish people were seen as a threat to Russian, Prussian and Austrian

power in the region and may have influenced the second partition of Poland

in 1793.

Click here for the map “Restored Poland / 1809-1813”

In the Napoleonic Wars of 1799 – 1815, the Polish

population supported Napoleon I (the French Emperor) in hopes he would help

restore Poland

as an independent state which was partially restored for a short period

between 1806 and 1813. After the fourth partition of Poland in 1815, Poland

was under foreign control for nearly 125 years, divided between Russia, Prussia

and Austria.

Insurrection

The 1830 Insurrection was an attempt by the Polish

people to restore the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth. Along

with restoring the Commonwealth, the more radical revolutionaries wanted to

eliminate foreign rule completely and the moderates wanted to re-enforce

their constitution. The revolution was not well organized and in 1831 Poland

declared independence only to have it taken away in May 1831 by the Russian

victory at Ostroleka. To punish the Polish people,

Russian leaders intensified "russification"

and withdrew many art and literary pieces from Poland

(Cambridge).

Click here for the map “Polish Lands

/ 1815-1914”

In 1863, a similar insurrection took place where an

"unconditioned and permanent emancipation and the complete enfranchisement

of every person in the Polish realm without regard to race, religion or

previous condition of bondage" was sought (Cambridge 378). The main attempt was to

benefit the peasantry and in return gain their support in the revolution.

It was in this second insurrection that Lithuania took up arms in support of Poland.

Sympathy from other European countries surmounted and the insurrection was

looked at as a "national uprising" although the Russians would

never admit to that (Cambridge).

French and English supporters lobbied for the restoration of the Polish state

under the terms of the Treaties of Vienna. The terms of this treaty would

include Lithuania.

The results of this insurrection left Poland with the task of "building from

the bottom up a restored nation" (Cambridge

386). The events of 1863 brought the Lithuanian speaking peasantry to the

front as a political force – it was also the last time Poland and Lithuania

would fight together for the restoration of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

(Suziedelis137).

The Great

Diet of Vilnius

In 1905, similar to what had happened in Poland in 1863, Lithuania

attempted to end "russification" and

achieve "national autonomy, a democratic political structure based on

universal suffrage and the equality of all nationalities in Lithuania"

(Suziedelis 124). Lithuania’s

goals were very similar to what Poland had asked for in the 1863

Insurrection and it has been speculated that one may have influenced the

other. Lithuania’s support

came in great numbers from Lithuanian communities in the surrounding areas of

Russia, Ukraine, Poland,

Latvia and East Prussia.

Obtaining support from the community was something Poland had intended with their

1863 revolution. In 1918, the Republic

of Lithuania was

formally declared.

Later

Relations between Poland

and Lithuania – The Vilnius Question

From the 14th century to 1795, Vilnius had been the

capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the administrative center for the

Lithuanian lands. It had also become a cultural center for both Poles and

Jews at the beginning of WWI. In 1918, Lithuanians felt Vilnius

was the proper capital of Lithuania

although the population in Vilnius

was mainly Polish, Jewish and Russian (in the surrounding area it was mainly

Lithuanian). However, Poles considered it their city and attempted to annex

it together with a portion of Lithuania

Click here for the map “Poland / 1918-1919”

The Soviet-Lithuanian Peace Treaty of 1920 gave Vilnius to Lithuania,

but Polish troops captured Vilnius

later that same year. The League of Nations stepped in to try and resolve the

dispute with the "Hymans Plan" which involved a "loose

Polish-Lithuanian Confederation" with Vilnius

belonging to Lithuania,

but Lithuania was not

interested in remaining linked with Poland. Poland officially annexed Vilnius in 1923.

Click here for the map “Poland / 1920 - 22”

When Poland

fell under German and Soviet rule, Vilnius was

transferred back to Lithuania

through the Soviet-Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Pact in 1939.

Click here

for the map “Poland

/1939”

Questions over Vilnius

still remain today but no serious attempts to recapture the city have been

made by Poland

and relations between the two countries have greatly improved.

Bibliography

Harrison, E.J.. Lithuania

Past and Present. London,

England: T.

Fisher Unwin Ltd, 1922.

This book was helpful in researching Lithuanian points of view in

regards to the "Vilnius Question" and for dates during the 15th

century wars with the Teutonic Order.

Jedlicki, Jerzy. A Suburb of Europe:

Nineteenth-Century Polish Approaches to Western Civilization. Budapest, Hungary:

Central European University

Press, 1999.

This book looks at Poland

from 1780 – 1880 and it’s take on national identity, development and the

academic growth of the country.

Jurgela,

Constantine. History of the Lithuanian Nation. New York, NY:

Lithuanian Cultural Institute, 1948.

This book contained a good, solid reference to Lithuanian history with

regards to wars, revolution and politics.

Kasprzyk, Mieczyslaw. http://www.kasprzyk.demon.co.uk/www/RisePower.html

1997. Accessed on 4/8/02.

This site was very helpful in explaining the history of Poland from

AD 800. It highlighted the Polish Army of 1550 – 1683, the revolution and

rebirth and ends with post war Poland. Also contains a list of

books and links on Polish history.

Kirby, David. Northern Europe

in the Modern Period The Baltic World 1492 – 1772. London, England:

Longman Group UK Ltd, 1990.

This source gives you a human aspect to the history of the Baltic States. It stretches from The Middle Ages to the

Rise of Russia. It contains maps documenting the changes in territories in

1500, 1617 and 1645. Easy to read and gives you a more inside look to the

society at the time.

Lerski, George. Historical

Dictionary of Poland 966 – 1945. Westport,

Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1996.

This dictionary was good for referencing specific events or names. It

gives sometimes pages of information on specific topics, although a Polish

bias is sometimes detectible. It is hard to use as a general reference if you

don’t know what you are looking for.

Ptaszycki, Stanislaw.

The Lithuanian Metrica in Moscow

and Warsaw: Reconstructing the Archives of the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press, 1984.

This book is full of primary documents such as a treaty between the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the King of Poland and portraits of Polish

kings. This is more for background information than for the actual research

it contains, which is mainly about the archiving systems of the Baltic Region

in the 17th – 18th century.

Rebas, Hain. "Baltic Regionalism??" Journal of

Baltic Studies 19, no 2 (1988): 101 – 116.

This article argues that the Baltic Region rejects the idea of

regionalism and has not been affected by the regionalism of other European

countries. It goes on to define "regionalism" and

"Baltic" and the relationships between Estonia

& Latvia with Poland, Finland

and Sweden.

Reddaway, W.F.. The Cambridge History of Poland. London, England:

Cambridge University Press, 1950.

Similar to the dictionaries used in how it was organized by specific

events.

Sanford,G. Senior

Lecturer in Politics, University of Bristol.

http://encarta.msn.com/find/concise.asp?mod=1&ti=761559758&page=7#5

Accessed on 4/8/02.

The history section of this site was somewhat useful in describing the

events from AD 840 until present. This section details the Piast Dynasty, the Jagiellonian

Dynasty, and the wars that led to the Polish decline.

Senn, Alfred Erich. "Lithuania’s

Fight for Independence The Polish Evacuation of Vilnius, July 1920." Baltic

Review 23 (1961): 32 – 39.

The article features letters from foreign commissioners in Riga addressed to the Secretary of State regarding the

state of affairs and negotiations between the Poles and Lithuanians after the

Polish evacuation from Vilnius.

Senn, Alfred Erich. "The

Polish Lithuanian War Scare, 1927." Journal of Central European

Affairs 21, no 3 (1961): 267 – 284.

This article discussed the League of Nations attempt to diffuse

conflict between Lithuania

and Poland which could

potentially cause conflicts in the rest of Europe.

Suziedelis, Saulius. Historical Dictionary of Lithuania. Lanham, MD:

The Scarecrow Press, 1997.

This, again, was a useful reference for specific events and dates. Not

a good resource for general history of Lithuania because you need to

know which event you are looking up.

Originally

published at http://depts.washington.edu/baltic/papers/

BACK TO THE BALTIC STATES

|