|

|

4

Russia under the Romanovs: Empire and

Expansion, 1613-1855

Legislation, civil

administration, diplomacy, military discipline, the navy, commerce and industry,

the sciences and fine arts, everything has been brought to perfection as he

intended, and, by an unprecedented and unique phenomenon, all his

achievements have been perpetuated and all his undertakings perfected by four

women who have succeeded him, one after the other, on the throne.

Voltaire, Russia under Peter the

Great ( 1763)

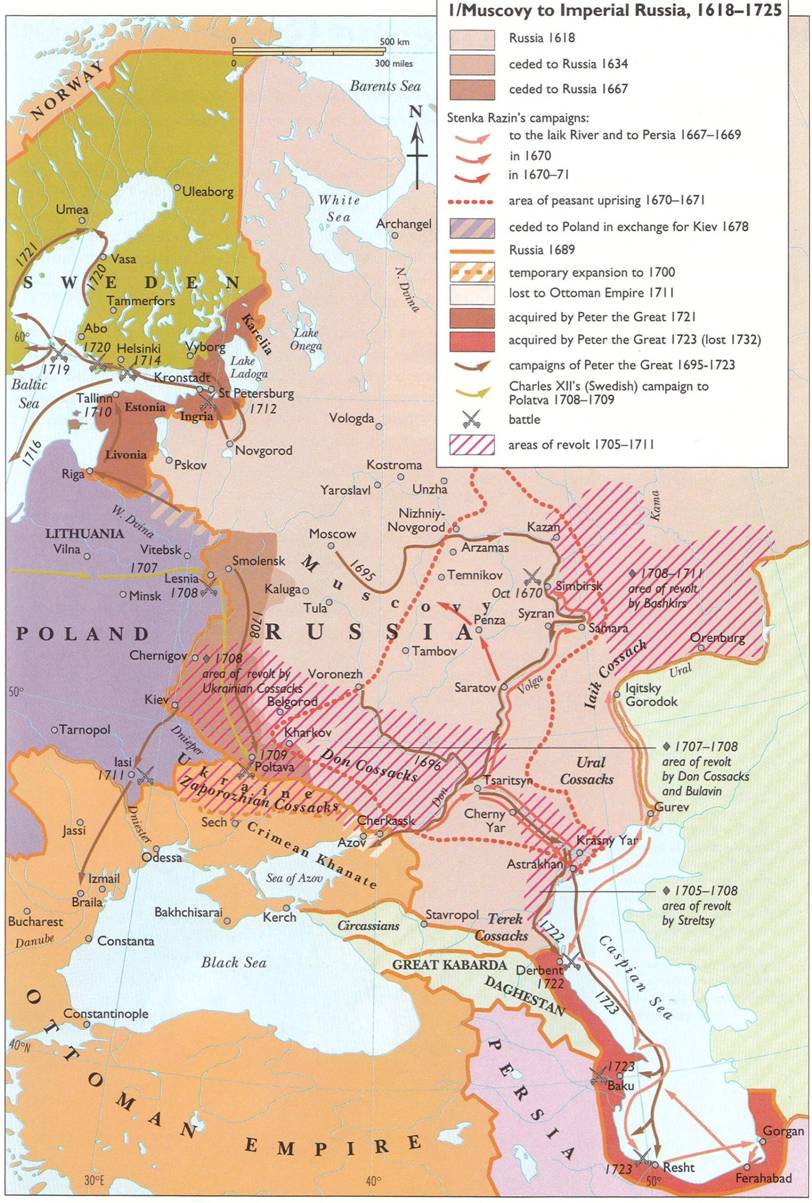

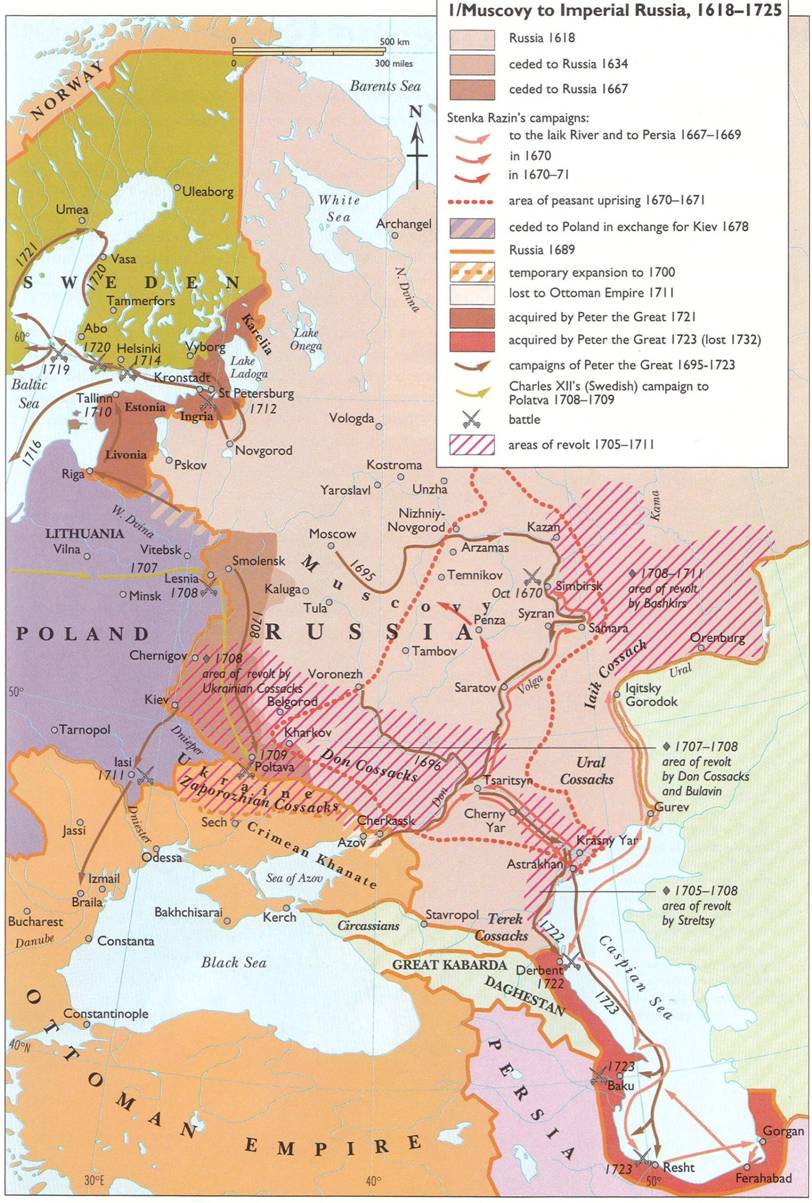

In the 112 years from the beginning of the

Romanov dynasty in 1613 to the death of Peter the Great in 1725, an isolated,

fragmented, and weak Russia evolved into a major European power with new

industries, a standing army, and a new capital. Russia in the late seventeenth

century was a far cry from Peter's ideal of a modern, efficient industrial

power, and he struggled incessantly with recalcitrant nobles, peasants, and townfolk

to Westernize Russian society. Peter's efforts to modernize medieval Russia

injected contradictions and contrasting perspectives that would fuel social

tensions and political disputes, which have persisted into the beginning of

the twenty-first century.

Most of the Romanov tsars who preceded Peter

were weak and ineffectual rulers; his father, Alexis, was probably the best

of the lot. Mikhail Romanov, selected as tsar at age sixteen in 1613, was not

able to put an immediate end to Russia's difficulties. According

to Nicholas Riasanovsky, Russia's

most pressing problems in the early Romanov years were internal disorder,

foreign invasion, and financial collapse. Mikhail's father, the Metropolitan

Filaret, served as the real power behind the throne until his death in 1633.

When Mikhail died, his son Alexis, a cultured but weak leader, ruled Russia from

1645 to 1676. Tsar Alexis frequently deferred to his boyar advisors, whose

greed and corruption provoked peasant and Cossack rebellions in 1648, 1662,

and 1670-1671. The last and most famous of these revolts was led by Stenka

Razin, a Don Cossack and hero of the common people who was eventually

captured and executed.

|

|

|

|

|

Tsar Alexis Romanov

|

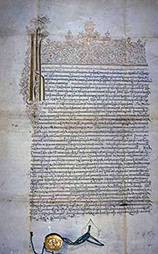

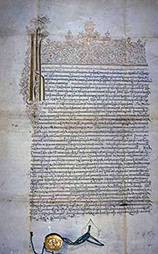

Edict of Tsar Alexis

|

Stenka Razin

|

In the first few decades of the Romanov

dynasty the power vacuum at the center strengthened the zemskii sobor (Assembly of the Land), which advised

Mikhail and Alexis, passed legislation in certain areas, and represented the

gentry and merchants against the boyars. Unlike the English Parliament,

however, the Russian zemskii

sobor never accumulated

enough power to challenge the tsar's authority; by the 1650s its influence

was waning. Peter the Great's strong centralized rule decisively ended any

chance of a representative legislature emerging in Russia.

Much of the groundwork for Peter's strengthening

of the Russian state was laid during the seventeenth century. State control

over society was embodied in a law code (Ulozhenie) of 1649. This

legislation, premised on the idea that inequality and rank were central to a

well-ordered society, formalized a rigid hierarchy of class relations, from

boyars and the highest church ranks, through the upper and middle service

classes, merchants, and townspeople, to peasants and slaves at the bottom of

the ladder. The Ulozhenie spelled out in detail the duties and

responsibilities of each social group--for example, their obligation to

provide carts for the postal service, the payment due an individual for

injured honor, or the sum that would be paid to ransom someone from foreign

captivity. These strict provisions tied the peasants more closely to the

land, ended what remained of their limited freedom of movement, and largely

eroded the distinction between serf and slave.

The seventeenth century was an age of great

exploration eastward, following in the path of the Cossack Ermak. Cossack

explorers reached the shores of massive Lake Baikal,

the largest body of fresh water in the world, in 1631. Fur and gold were the

primary motivations for opening up this frigid and inhospitable region. By

about 1650 Russia controlled much of Siberia, and by the time Peter I was

crowned tsar, in 1689 (his sister Sofia had governed as regent from 1682 to

1689, since Peter was only ten years old when he became tsar), Russian

territory extended to what is now the Bering Strait. It was Peter the Great

who, in 1724, sent the German explorer Vitus Bering eastward to map the icy

body of water dividing Russia

from North America.

North and central Siberia

at that time was an area inhabited by small tribal peoples--the Yakuts,

Buriats, Chukchis, and others--whom the Russians easily subdued. However,

further south Russia's

explorers clashed with a powerful neighbor, China, whose Qing dynasty rulers

feared Russian traders might strike an alliance with the fierce nomadic

warriors on their northern borders. In 1689 the Russians and Chinese, with

the assistance of Jesuit missionaries acting as interpreters, signed the

Treaty of Nerchinsk. This agreement granted Russia

most of Siberia while reserving the area around the eastern Amur River to China. The

Treaty of Nerchinsk is a critical event in Russo-Chinese relations, since it

demarcated their border over the course of the next three centuries.

Since the fall of Kiev

to the Mongols in 1240 Ukraine

had been outside Moscow's

domain. By the late fourteenth century much of Ukraine (the word means "the

border") had been incorporated into Catholic Lithuania, later to be

supplanted by joint Polish-Lithuanian rule. Crimean Tatars controlled the

southern part of what is now Ukraine.

Ivan the Terrible had captured some of the eastern Ukrainian lands for

Muscovy; however, Poland

continued to threaten Moscow

through the Time of Troubles. The Lublin Union of 1569, joining Poland and Lithuania,

restrained Moscow's

influence in the southwest. The formation in 1596 of a Uniate branch of the

Russian Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox in rite but formally subordinate to

Rome, exacerbated religious tensions in Ukraine.

In the early seventeenth century Zaporozhe Cossacks, freebooters living

along the southern reaches of the Dniepr

River, fought the Poles

in their role as protector of the Orthodox. Polish repressions in Ukraine

sparked the revolt of 1648, led by the Cossack Bogdan Khmelnitsky. The

Cossack leader and his followers captured Kiev

but, under pressure from the Poles, turned to Moscow for protection. Ukraine suffered as a battleground between Russia and Poland

for thirteen years, from 1654, when Ukraine

swore allegiance to Tsar Alexis, to 1667, when the Treaty of Andrusovo

granted all of Ukraine

east of the Dniepr River, together with Kiev,

to Moscow.

While medieval Russia had by 1689 developed into

a physically imposing country, from the perspective of most Europeans it

remained a curious, rather primitive nation of fur-capped barbarians. Peter

the Great both expanded Russian territory and sought to modernize his country

by adopting European customs, manufacturing practices, and military

technologies. Peter relied on brute force and the strength of his will to

create a modern nation that would be internationally respected.

Peter's favorable orientation toward the

West was acquired in childhood. Although he was formally proclaimed tsar at

age ten following the death of Tsar Feodor in 1682, Peter's half-sister Sofia

assumed the regency. Court politics quickly degenerated into vicious

intrigue. Neglected, Peter frequently entertained himself in the foreign

quarter of the capital. Skills learned from his Dutch and German friends were

reinforced by a tour of the Continent in 1697. As a child he assembled play

regiments to conduct "war games"; these formations evolved into two

elite guard regiments, the Preobrazhenskii and Semenovskii.

Young Tsar Peter Romanov

Peter was very intelligent, energetic,

insatiably curious, and physically imposing at nearly seven feet tall. He was

very much a hands-on ruler, insisting on learning some twenty different

trades such as carpentry, shipbuilding, and shoemaking, and in keeping with

his commitment to meritorious advancement, worked his way up through the

ranks of the army. Peter also founded the Russian navy, starting with the Sea of Azov fleet, needed to defeat the Turks during

the 1695-1696 campaign. Later he constructed the Baltic fleet to pursue the

Great Northern War with Sweden.

Peter studied naval construction at Dutch and English shipyards, recruited

European experts to advise Russians in the military sciences, and built a

large ship entirely by himself.

Although committed to modernizing Russia militarily, economically, and socially,

Peter rejected political liberalization as inappropriate for Russia. When

the streltsy (royal musketeers) revolted in 1698

in an attempt to restore Sofia to the throne,

Peter cut short his European tour, cruelly executed over a thousand of the

conspirators, sent others into exile, and forced Sofia and his first wife, Evdokia, into a

convent. Later, Peter would decentralize Russian government, enact civil

service reforms (by establishing the Table of Ranks), and create a Senate to

administer affairs of state while he was absent from the capital. While these

reforms provided for more efficient administration of state affairs, the

absolute power of the tsar was not eroded, as happened in Britain

during the same period. Rather, Peter's reforms strengthened the power of the

state and the tsar.

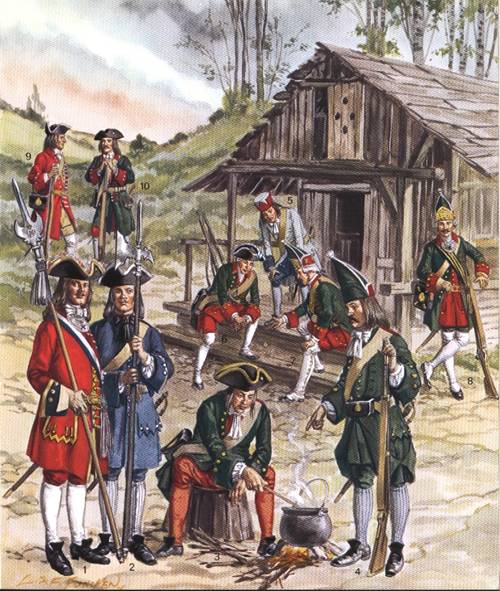

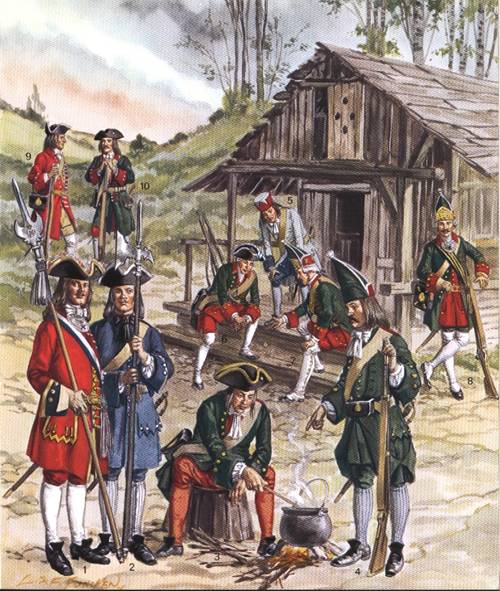

Above:

Traditional Streltsy (royal musketeers) /

1698

Below: Peter’s

New style soldiers / 1698 – 1721

Much of Peter's reign was consumed with the Great Northern War against Sweden.

Following the conclusion of a treaty with the Turks, Peter joined his Saxon

and Danish allies in declaring war on Sweden. Russia was

promptly defeated by a much smaller force of Swedes, led by the

eighteen-year-old military genius King Charles XII, at the battle of Narva in

November 1700. This major loss led Peter to rebuild his army, including the

famous decision to melt down Russia's

church bells to make cannonballs. Peter also introduced general military

conscription, constructed a Baltic fleet, and laid the foundations for a new

northern capital on the Gulf of Finland as

part of his northern campaign. In July 1709 Russian forces destroyed the

Swedish army at the battle of Poltava, in Ukraine.

Although fighting with Sweden

dragged on until 1721, when the Treaty of Nystadt finally brought an end to

hostilities, the victory at Poltava stunned

Europe and confirmed Russia's

emergence as a major military power. Russia

now was an established presence in the Baltic region, with Peter's new

capital city, St. Petersburg,

positioned as his window on the West.

St. Petersburg and Peterhof (painting by Vasiliy Sadovnikov/ 1840 )

Peter's constant military campaigns expanded

Russia's

boundaries, but at considerable cost to the Russian people. In order to pay

for the armies, ships, and armaments the Russian government imposed heavy

financial burdens on the population. Mills, beehives, bath houses, and

coffins were all taxed to provide revenue for the army. In keeping with

Peter's goal of discouraging traditional Russian practices, beards were also

taxed (some stubborn court figures had their facial hair shaved off by the

tsar himself!). Late in his reign a head tax was imposed on all male

peasants, in place of the household and land taxes, to make it more difficult

to evade their assessments.

Russia's middle and upper

classes were also expected to fulfill their obligations to the state. The

nobility were registered and were required to serve either in the military

ranks or in the growing civil bureaucracy. Government officials were to be

promoted according to merit. The Table of Ranks, established in 1722,

essentially replaced the medieval system of state appointments corresponding

to the importance of one's noble family (mestnichestvo), which had

been abolished in 1682. The Table listed fourteen ranks each in the military,

civil, and judicial services. Since promotion was to be based on

accomplishment, this system provided for limited upward social mobility. A

member of the lower class who attained the fifth rank would be granted status

in the gentry for life; reaching the ninth rank conferred gentry status on

one's heirs.

New laws on provincial and municipal

government were enacted in 1719 and 1721, respectively, in an attempt to

separate judicial and administrative functions. Late in his life Peter also

sought to create a more activist state to provide social services, govern the

economy, and create a respect for law and a sense of communal responsibility.

And yet there was no equivalent to the American concept of law limiting

government. As the British historian B. H. Sumner has pointed out, Peter

relied heavily on his guards officers to override ordinary government, rule Ukraine, and

force officials to carry out his edicts. This practice of relying on a state

above the state had been employed by Ivan the Terrible and his oprichniki, and would be used

in later years by Russian tsars and Soviet dictators.

When Peter I died in 1725, he left a Russia

transformed. His rule embodied both the technological and rationalistic

spirit of the West and the autocratic and cruel properties of the East. He

injected these conflicting values into Russian society, creating tensions

that would endure for centuries. The upper classes had accepted many of the

European customs he forced on them, while the great mass of the population

remained culturally Russian. Over the next century this cultural divide would

widen even further, creating virtually two worlds having little in common.

Only in the late nineteenth century were there any serious efforts to bridge

the gap, not via reform, but through various populist and terrorist movements

that would destabilize Russian society and prime it for revolution.

RELIGION AND CULTURE

The Russian Orthodox religion underwent a

series of reforms in the mid-seventeenth century which pitted traditionalists

against those who would modernize and revitalize Russian Orthodoxy, leading

to a major schism in the Church. The proposed reforms also pitted church

against state. Patriarch Nikon, who had assumed office in 1652, promoted a

number of "corrections" to Orthodox religious texts and rituals, to

bring the Church more into line with prevailing Greek practice. An Orthodox

Church council meeting in 1666-1667 deposed the ambitious Nikon but enacted

his proposed reforms. While outsiders might consider the changes to be rather

trivial (for example, making the sign of the cross with three fingers rather

than two), many of the faithful rejected these innovations.

These Russian protestants, the Old

Believers, often fled east to the wilds of Siberia

or to remote areas in the north. The more extreme congregations burned themselves

to death in their churches rather than give in to the ecclesiastical

authorities. As cultural historian and Librarian of Congress James Billington

has observed, through their self-imposed seclusion, the Old Believers

relinquished Russian urban culture to foreigners and the Westernized service

nobility. Old Believer communities preserved the mystical and

anti-Enlightenment elements of Muscovite society into the early twentieth

century.

Russian culture became increasingly

secularized in the decades after the Great Schism. Billington notes that

theological education in Russia

became more Latin than Greek in content--more inclined to rational discourse,

and therefore more secular. The Orthodox Church had been opposed to music,

sculpture, and portraiture; under Tsar Alexis and the regent Sofia

European-style paintings, literature, poetry, and historical writing made

inroads into Russian culture. During Peter's reign, though, there was not

much progress in either philosophic or artistic culture.

Peter the Great was tolerant of different

religious faiths. He frequently invoked Russian Orthodoxy when it suited his

needs, but he was also notorious for organizing blasphemous drinking parties

ridiculing the Church hierarchy. More important, Peter made the Orthodox

Church subordinate to government authority, as part of his broader efforts to

strengthen the Russian state. In 1718 he established an Ecclesiastical College,

or Holy Synod, a sort of governing board of clerics, to replace the

independent patriarchate. The Ecclesiastical

College was one of nine

specialized administrative bodies patterned after the German model.

Subsequently, he created the office of Chief Procurator of the Holy Synod (

1722) to monitor and enforce state control over Church affairs.

With the abolition of the patriarchate and

the creation of the Holy Synod and its head, the Chief Procurator, Peter

brought an end to the symphonic relationship of Orthodox Church and Russian

state. No longer the moral conscience of the nation, the Church now was

impressed into state service. Clearly, Peter viewed the Church with its

conservative, bearded clerics as a mainstay of old Russia. His son and heir Alexis,

who was weak and unfit to rule, had allied himself with some of the more

reactionary clergy in opposing his father's reforms. Lured back from his

refuge in Austria

in 1716, Alexis was tortured and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul fortress,

where he died in 1718. This experience likely confirmed Peter's intention to

subordinate the Church firmly under state control.

Education in Russia made major advances under

Peter the Great, which were continued by his eighteenth-century successors.

Peter's view of education, however, was narrow and highly functional. In his

estimation, broad education was less useful than practical training in

military science, construction, or languages, which he deemed vital to

building a stronger Russian state. In keeping with Peter's determination to

make Russia the equal of

Europe, the Russian

Academy of Sciences was

established in 1725. Although initially both instructors and students were

German, the academy soon could boast of Russian luminaries, among them the

poet, scientist, historian, and educator Mikhail Lomonosov ( 1711-1765).

Mikhail Lomonosov as seen by Russian artist Anatoliy

Vasiliev

Moscow

University, Russia's first and most

prestigious institution of higher education, was founded in 1755 with the assistance

of Lomonosov. Lomonosov was Russia's

first Renaissance man. He studied in Germany,

at the University of Marburg, and upon his return to Russia

adapted Germanic practices to Russian higher education. Lomonosov was a

pioneer in chemistry, experimented with electricity, and promoted scientific

approaches to marine navigation. A Russian nationalist determined to place

the Russian language on a par with European tongues, his study of Russian

grammar contributed significantly to the development of the country's

language and national identity.

Elizabeth ( 1741-1762) and Catherine II (

1762-1796) carried out vigorous building programs, making St.

Petersburg into one of Europe's

most beautiful cities. Under Elizabeth the

great Italian architect, Bartolomeo Rastrelli, designed some of Russia's most prominent landmarks, including

the Catherine Palace

at Tsarskoe Selo, Smolnyi Convent, and the fourth Winter

Palace in St. Petersburg. The last of these, the

chief residence of later tsars and tsarinas, is now the great Hermitage

museum. Catherine sponsored architectural competitions and depleted Russia's already strained treasury to

construct such monuments as the Merchants' Arcade (Gostinyi Dvor) in St. Petersburg, designed by Vallen de la Mothe, and

Vasilii Bazhenov's great Kremlin Palace in Moscow.

Women made marginal advances during the late

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The regent Sofia had freed herself and

other noble women from the terem,

which consigned them to household seclusion; Peter commanded them to appear

in public to dance and converse with men, in the European style. The examples

of Elizabeth and Catherine the Great encouraged women to occupy more

prominent roles in Russian society. For example, under Catherine II a member

of her royal court, Princess Dashkova, served as director of the Russian Academy and the Imperial Academy of

Sciences.

Emperor Paul I

Paul I, Catherine's son, erased much of the

progress made by women n the eighteenth century

with his edict of 1797. This measure mandated succession by primogeniture

(through the eldest son), thus privileging all possible male heirs to the

throne ahead of women. Aleksandr I continued his father's policy of

relegating women to marginal roles in Russian politics, as did his successor,

the ultraconservative Nicholas I. However, Barbara Alpern Engel, in her study

of nineteenth-century women (in Clements et al., Russia's

Women), has noted that German Romanticism and French and British utopian

socialism created a culture among the Russian intelligentsia more accepting

of women's participation in political and social debates. By the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries women had become key actors in the

Russian revolutionary movement.

CATHERINE THE GREAT

Peter died before he had the chance to

designate a successor. His wife Catherine I ruled for less than two years and

was followed on the throne by Peter's grandson, Peter II ( 1727-1730). Peter

II was only eleven years old when elevated to the throne, and he accomplished

nothing. Two tsarinas followed--Anna I ( 1730-1740) and Anna II ( 1740-1741).

The two Annas were distinguished mostly by their appetites for German culture

and sexual adventures with court officials of either gender. Elizabeth I

(1741-1762), Peter I's daughter, deposed Anna Leopoldovna, banished her to Germany, and

imprisoned the only male Romanov successor, the infant Ivan VI, in the Peter

and Paul fortress. Elizabeth

realized that much of the popular opposition to Peter I's successors stemmed

from their German nationality. For this reason, historian Bruce Lincoln

argues, she consciously sought to restore Russian pride by promoting Russian

culture, reducing the number of foreigners at the court, and, in contrast to

her predecessors, taking only Russian lovers.

Peter III served for only a few months after

the death of Elizabeth

I. He adored military affairs, idolized Prussia's

leader, Frederick

the Great, and was so detested by the royal guards that they willingly

deserted him in favor of his wife, a German-born princess from Anhalt-Zerbst

named Sophie Auguste Frederike. Sophie was brought to Russia at age

fourteen as a bride for the weak and ineffectual Peter Ulrich, Duke of

Holstein. She mastered Russian, converted to the Orthodox religion, and

quickly learned the game of court intrigue. The young German princess learned

to hunt and became an expert horsewoman. She adopted the name Catherine and,

although she married Peter, the two were not close and did not produce any

children. In years to come the ambitious and intelligent young woman took a

series of lovers, one of whom, Count Grigorii Orlov, organized the coup that

in 1762 deposed her husband and crowned Catherine II Empress of all Russia.

Empress Catherine II

Like Elizabeth,

Catherine deliberately minimized her European connections, stressing her

commitment to Russia

to win the support of the nobility. However, Catherine continued the

Westernization process begun by Peter the Great. While Peter's interest in

the West had been practical, Catherine's was largely philosophical and

cultural. Early in her reign Catherine sought to embody the ideas of the

French philosophes in a progressive law code, the Great

Instruction, which combined enlightenment with Russian absolutism. This

document embodied Catherine's ideas of herself as a rational, enlightened

sovereign who served the Russian people. It also illustrates the didactic

character of her personality. A commission of representatives of various

social groups was assembled to codify the Great Instruction, but quarrels

among the nobility ultimately undermined Catherine's efforts to implement a

coherent program of reform.

Catherine read voraciously as a young woman,

and as empress selectively drew her political inspiration from Europe's greatest thinkers, including Voltaire,

Diderot, and Montesquieu. She used Montesquieu's writings, for example, to

justify exercising strong, centralized, and absolute authority in the

extensive Russian empire. However, his concept of the separation of

legislative, executive, and judicial powers, which was later adopted by the

American revolutionaries, was deemed inappropriate for Russia.

Catherine the Great was determined to bring

the great ideas of the Enlightenment to Russia. She was a great patron of

the arts--theatrical productions, poetry, and painting all flourished under

her. The publication of books and periodicals mushroomed in the early years

of her rule, and most of these were secular. One satirical magazine Catherine

sponsored, Odds and Ends,

mocked the Russian nobility, who constituted the bulk of the reading public.

In another, Hell's Post,

Catherine herself published an article deriding Russian doctors as ignorant

quacks who killed more patients than they cured.

Russia's adoption of

European customs was largely superficial. The nobility learned French and

German, practiced fencing and dancing, and read the latest European works.

Russian military leaders often paid more attention to the spectacle of the

parade ground than to the fighting ability of the troops. Although priding

herself on being an enlightened mon arch, Catherine could not tolerate

criticism of her rule or of the general principles of Russian autocracy. When

Alexander Radishchev published his biting critique of serfdom in A Journey from St. Petersburg to

Moscow ( 1790), Catherine

ordered copies of the book destroyed and exiled the author to Siberia. The French Revolution's terror against the

aristocracy so alarmed her that she ordered all the writings of the philosophes destroyed.

Catherine's success depended on her alliance

with the Russian gentry, and she pursued policies that clearly favored the

upper classes. A Charter of the Nobility in 1785 recognized the district and

provincial gentry as legal bodies and granted them the right to petition the

court directly. The status and treatment of Russia's peasants deteriorated as

the nobility's privileges expanded. Serfdom was strengthened, and expanded

through Ukraine and into

the Don region of southern Russia.

Serfs were completely subject to their masters; their mobility was strictly

limited, and they could receive harsh punishment even for submitting a

petition to the tsarina.

Social grievances that had accumulated among

the lower classes exploded late in 1773 when a Cossack, Emelian

Pugachev, proclaimed himself to be Peter III and led an uprising in the

Urals. Pugachev's promise of freedom from taxation, serfdom, and military

service, and his threats against landlords and officials, won him a

substantial following among Cossacks, Old Believers, serfs, metalworkers,

Tatars, and other disaffected elements. For over a year his ragtag troops

terrorized the central Urals region, but ultimately his forces were defeated

by the Russian army. Pugachev was sent to Moscow in chains, where he was brutally

dismembered and his body burned as an example to other potential rebels.

While Catherine could be, and frequently

was, cruel to the lower classes, she enhanced the privileges of the Russian

gentry. She often took a personal interest in handsome young men, promoting

their cultural and intellectual development while enjoying their company as

lovers. Possessed of a strong pedagogical streak, the empress founded the

Smolnyi Institute for young noblewomen in 1764, and the following year established

a school for young women of non-noble birth. She created a Free Economic

Society to encourage agricultural experimentation, and in 1786 set up a

system of elementary schools in provincial cities to provide basic education

to the children of free urban classes. Catherine also established a network

of confidential hospitals to treat venereal disease, and decreed the

formation of Russia's

first Medical Collegium in 1763.

Catherine

commissioned a wave of construction by noted Italian, French, and Russian

architects in St. Petersburg, Moscow,

and Kiev.

Giacomo Quarenghi designed the Smolnyi Institute in St.

Petersburg, the State Bank, the Horse

Guards Riding

School, and the Academy of Sciences.

At Catherine's request Etienne Falconet created "The Bronze

Horseman," an impressive monument to Peter the Great, mounted on a huge

granite pedestal and placed not far from St. Isaac's Cathedral, in the center

of St. Petersburg.

The construction of St. Isaac's, a beautiful circular cathedral reminiscent

of St. Paul's in London, was begun in 1768, although it was not completed for

another ninety years.

ECONOMICS AND SOCIETY

Under Peter the Great Russia's textile,

mining, and metallurgical industries expanded rapidly. As industry expanded, state

peasants were often forced to work under inhuman conditions in the new

factories. The government squeezed the peasantry for more revenue and

ratcheted up the nobility's service obligations to the state. With the census

of 1719, all male members of a household were subject to taxation. This

eliminated the distinction between slaves and serfs and marked the end of

slavery as an institution in Russia.

Slaves did not pay taxes, and the landowners frequently tried to avoid having

to assume the tax burden for their serfs by declaring them slaves. Peter's

census eliminated this tax loophole.

Peter sought to make Russia more self-sufficient through

mercantilist policies, protecting Russia's new industries from

foreign competition and using the state as an engine of economic development.

The government encouraged the development of private industry, but with

limited success. A few nobles and merchants established factories, often with

state assistance, but the entrepreneurial mind-set was very weak in Russia.

In the eighteenth century, about 90 percent

of Russia's

population consisted of peasants; 4 percent lived in towns; while the final 6

percent consisted of nobility, clergy, bureaucrats, and military personnel. Russia's

lower classes--Cossacks, peasants, village priests, and laborers-were

resentful of the heavy tax burdens, hostile toward the foreign influences

that had come with Peter's reforms, and infuriated by the tsar's insulting

behavior toward the Church.

This anger boiled over in occasional

rebellions during the first decade of the eighteenth century. These and later

rebellions by the lower classes were not directed against autocracy (they

could scarcely conceive of an alternative system), but rather against those

bureaucrats and officials whom they believed were frustrating the will of the

tsar. Another common theme in peasant revolts was the search for the

"true tsar." Convinced that the figure on the throne was an

imposter, the rebels often took up the cause of a charismatic pretender.

Conditions worsened for the peasants under

Catherine the Great. Their tax burden increased substantially, serfdom was

extended into Ukraine

and the Don region, and the gap between the upper and lower classes widened.

The nobility became increasingly privileged under Catherine; she released

them from compulsory state service in 1762, and often distributed land with

serfs to those who supported her politically. Lords were free to use serfs as

they wished, short of executing them. They could beat them, sell them or

their families, send them to the army or to work in the factories, win or

lose them at cards. A Russian serf's life was not much different from that of

an American slave in the antebellum South.

FOREIGN AFFAIRS

Russia's expansion of

empire continued under Catherine the Great. In the first Turkish War of her

rule ( 1768-1774) Russian armies defeated Turkish forces in Bessarabia and

the Balkans, and then captured the Crimea.

The Treaty of Kuchuk Kainarji granted Russia

strategic points along the Black Sea coast, although Moldavia and Wallachia in south-central Europe

were returned to Turkey.

However, Russia extracted

promises from the Muslim Turks that they would protect Christian churches in

these regions, and would allow construction of an Orthodox church in the

Turkish capital, Constantinople. In the

second Turkish War of Catherine's reign ( 1787-1792) the great Russian

general Aleksandr Suvorov captured the fortress of Ismail, threatened

Constantinople, secured Russia's control over the Crimea and Black Sea

region, and settled the Turkish threat.

Russian territory also expanded westward

with the successive partitions of Poland, in

1772, 1793, and 1795. By the eighteenth century Poland had

become weak and ripe for dismemberment. Polish kings were elected and had to

share power with a fractious parliament, or sejm.

The Polish nobility were extremely jealous of their prerogatives, including

the liberum veto, the

ability of any one deputy to stymie parliamentary business. In the three

partitions Russia, Prussia, and Austria

incorporated the eastern, western, and southern parts of Poland, respectively, wiping the country off

the map of Europe. Through the partitions Russia gained White

Russia ( Belarus), western

areas of present-day Ukraine,

and Lithuania.

Poland's

great patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who had aided the Americans in their fight

for independence, led a futile uprising against the Russians in March 1794.

Suvorov and the Russian army crushed the Poles, leaving a legacy of

bitterness between the two peoples that would endure for over two hundred

years.

PRELUDE TO REFORM: ALEKSANDR I

When Catherine died in 1796 she was

succeeded by her son, Paul I ( 1796-1801). Paul, who suffered from mental

problems, deeply resented being excluded from state affairs by his mother for

a decade and a half. Paul had coped with his frustration by conducting

military exercises at Gatchina, his estate outside St. Petersburg, attending to every detail

of the parade ground. Paul's obsession with rituals, his abuse of power, and

his chaotic domestic and foreign policies left Russia weakened. Attacks on the

nobility's privileges together with mismanagement earned him many enemies. In

March 1801 a group of conspirators murdered him in his bedroom. Paul's eldest

son, Aleksandr, was aware of the plan to depose his father, and reluctantly

supported the plot, but was dismayed and wracked with guilt over his father's

death.

Emperor Aleksandr I

This inauspicious beginning troubled

Aleksandr I, who would rule from 1801 to 1825. The new emperor surrounded

himself with a circle of young, reform-minded friends, the "Unofficial

Committee," dedicated to promoting Russia's economic development and

Westernization. The Russian Senate, comprised of leading noblemen, proposed

measures that would have enhanced their powers and limited those of the tsar.

Aleksandr initially compromised, permitting the Senate some supervisory

powers over the government bureaucracy and the "right of

remonstrance," questioning tsarist decrees that violated law or past

practice. However, Aleksandr soon rescinded even these limited concessions to

sharing power.

Mikhail Speransky, the son of an Orthodox

priest and a brilliant academic, worked his way up the civil service ranks

and by 1807 had become Aleksandr's chief political advisor. Speransky

advocated reorganizing Russia's

political system to introduce a form of separation of powers: an executive

branch comprised of ministers; the Senate as chief judicial body; and an

indirectly elected State Duma serving as legislature. These limited reforms,

which embodied Speransky's notion of a state based on the rule of law, and

which could have set Russia

on the path to a constitutional monarchy, were rejected by the tsar.

Aleksandr could not accept the idea of legal restrictions on his authority,

and adopted only Speransky's proposal for a State Council, which was created

in 1810.

Speransky also promoted the idea of merit

and competence in state service through compulsory examinations, antagonizing

many of Russia's

inept and corrupt bureaucrats. In general, education made great progress

during Aleksandr's reign. At the beginning of his reign Russia had only one university, in Moscow. By 1825 five

additional universities had been created, at St.

Petersburg, Kazan, Vilnius, Kharkov,

and Dorpat (the German university). Many of the nobility resented the

egalitarian orientation of these developments and blamed the erosion of their

privileges on Speransky. Under pressure, the tsar dismissed him in 1812.

Aleksandr's advisors agreed that serfdom was

a backward institution and recognized the need for reform. In an attempt to

reduce the nobles' privileges Paul had reduced the serfs'barshchina,

their labor obligation to the landlords, to three days per week, from an

intolerable high of five or even six. A law passed by Aleksandr in 1803

permitted landowners to free their serfs either individually or in groups,

but only some 50,000 were freed as a result of this legislation.

International Affairs

Russia under Aleksandr I

was becoming a nationalistic, militarily powerful European country. Expansion

of Russian presence in the Caucasus during

the first decade of Aleksandr's reign led to the Russo-Persian War of

1804-1813 and the Russo-Turkish War of 1806-1812. Russia's

victory in both conflicts resulted in the incorporation of Georgia, home

to an ancient mountain people who, like the Russians, followed the Orthodox religion.

Further to the north, war with Sweden

(1808-1809) won control of Finland

for the Russian empire.

The conflict with France, however, dominated

Russian foreign policy in the early nineteenth century. Leo Tolstoy's

monumental novel War and

Peace commemorates the

decade of struggle against the French and presents a fascinating portrait of

Russian life during this period. In the first conflict, from 1805 to 1807, Russia and its allies, Austria, Britain,

Sweden, and Prussia,

could not defeat the French and were forced to sign the Treaty of Tilsit in

July 1807. Aleksandr I and Napoleon met on raft in the Niemen

River, in Poland, to sign the treaty.

Europe was effectively divided between France

and Russia, and the latter

agreed to enforce a "continental blockade" against Britain, a

major trading partner, in an attempt to weaken its export-oriented economy.

Tensions between Russia

and France

mounted over the next five years. French attempts to establish influence in

southeastern Europe and the eastern Mediterranean antagonized the Russians,

while the blockade against Britain

harmed the interests of Russia's

landlord class. In June 1812 Napoleon led a force of over 400,000 troops in

an invasion of Russia;

eventually, this number increased to about 600,000. Roughly half of

Napoleon's forces were French, the other half conscripts or volunteers from

countries he had conquered. These included Poles determined to free their

country from Russian rule, Germans, Spaniards, and other mercenaries. Russia could

field only half as many troops. As Napoleon marched through Vilno, Vitebsk, and Smolensk

toward Moscow,

the Russian forces under the aged and obese Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov

gradually fell back rather than engage the numerically superior enemy

directly.

Russian forces did challenge the French at

the village of Borodino,

just west of Moscow,

on September 7. Although the Battle of Borodino lasted only one day, the two

sides suffered a total of 100,000 casualties. Kutuzov withdrew to the

southeast, and Napoleon entered Moscow

a week later. Whether deliberately or by accident, scores of fires broke out

in the ancient city, depriving the French of food and shelter. On October 19

Napoleon decided to withdraw his forces. Kutuzov's army denied the French a

more southerly retreat, forcing them to retrace their steps along the

devastated invasion route. Hunger, disease, cold, and constant harassment by

Cossacks and peasant detachments reduced Napoleon's Grande Armée to a mere 40,000 troops by the end

of the year.

Kutuzov's forces pursued the French dictator

into Europe and, with the aid of Austria,

Prussia, and Britain, defeated France

and occupied Paris

in March 1814. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815 Aleksandr I and the allies

presided over the redrawing of Europe's

boundaries. Russia now

posed as the defender of stability in Europe; through the remainder of

Aleksandr's reign and that of his brother Nicholas I ( 1825-1855) Russia stood as a bulwark of monarchical order

against the liberal and revolutionary movements of nineteenth-century Europe.

The Napoleonic wars strengthened Russia's sense of national identity and

popular patriotism while enhancing Russia's position as a world

power. The invasion sparked widespread sacrifice for Mother Russia among all

social classes. As British historian Geoffrey Hosking has noted, the Russian

peasants were motivated by fear of the invaders destroying their homeland and

by expectations that loyal service to the tsar would be rewarded with land

and freedom. However, the nobility opposed all serious reform efforts, and

Aleksandr's increasingly mystical religious leanings stifled the reformist

impulse. A member of Aleksandr's original Unofficial Committee, Nicholas

Novosiltsev, in 1820 proposed dividing Russia into twelve large,

relatively autonomous provinces, but this reform too was never enacted.

In place of reform, reaction and

obscurantism characterized the later years of Aleksandr's reign. One of his

closest advisors, Count Alexis Arakcheev, convinced the tsar to sanction the

creation of Prussian-style military colonies, which combined agricultural

production with military training. Arakcheev, a cruel landowner, commanded

all the women of his estates to produce one child every year. Designed to

reduce the expenses of maintaining a large standing army, the colonies became

repressive, mismanaged experiments that provoked popular resistance among the

lower classes.

Another prominent official, Minister of

Education Prince Aleksandr Golitsyn, believed that all useful knowledge was

contained in the Bible and distrusted secular learning. Golitsyn imposed an

intolerant religious doctrine on Russia's schools and

universities, dismissed teachers who advocated liberal or

"free-thinking" perspectives, and placed religious fundamentalists

in charge of education. University students resented the military-style

discipline, censorship, and compulsory attendance at religious services. Over

time, the most disaffected elements of the intellectual class and the

aristocracy began plotting against the government.

REVOLT AND REPRESSION: NICHOLAS I

Frustrated by Russia's inability to change, a

number of young nobles formed secret political societies that advocated a

variety of reform measures. From their experience in the Napoleonic wars,

these former officers had become painfully aware of Russia's backwardness compared to Europe. When Aleksandr died in November 1825, the

conspirators quickly decided to launch a revolt on December 14, the day

Aleksandr's brother Nicholas I was to ascend the throne. Poorly planned and

executed, the Decembrist Revolt was easily crushed when Nicholas ordered

troops loyal to him to fire on the demonstrators, who had gathered in St. Petersburg's Senate Square.

Five leaders of the revolt were sentenced to death, and over one hundred were

exiled. Among the pantheon of Rus sia's revolutionary heroes, the pampered

aristocrats' wives who gave up a comfortable life to accompany their husbands

to Siberia provided an example of loyalty and sacrifice that inspired later

generations.

Emperor Nicholas I

Nicholas' thirty-year reign (1825-1855) is

generally described as conservative, militaristic, and repressive. His

minister of education, Count Sergei Uvarov, expressed the ideology of the

period in a policy of "Official Nationality," consisting of three

principles--Russian Orthodoxy, autocracy, and nationalism. Orthodoxy provided

the religious values to unify society and the concept of divine right to

legitimize the sovereign's absolute power. Defending autocracy meant

rejecting any constraints on the tsar's authority, whether in the form of

power sharing with other institutions or a greater role for popular

participation in governance. Nationality privileged the Russian people as the

dominant culture within the multinational empire; further, it implied that

Russian civilization was superior to that of the much-emulated Western

nations.

In his effort to exercise absolute control

over Russia,

Nicholas curtailed the authority of the Committee of Ministers, Senate, and

State Council, preferring instead to operate outside the formal state

machinery. Early in his reign Nicholas established His Majesty's Own

Chancery, consisting of several departments dealing with law and public

order, education, charity, state peasants, and the Transcaucasus region.

Mikhail Speransky, Aleksandr's reformist minister, was given responsibility

within the Second Department to reform Russia's antiquated laws. By the

early 1830s a Complete Collection of the Laws of the Russian Empire was

published, in fifty-five volumes, in an effort to reduce the arbitrary and

tyrannical influence of Russia's

administrators.

In the interests of preserving domestic

political order, however, Nicholas readily adopted draconian measures.

Officials of his Third Department, a predecessor of the Soviet KGB secret

police, became notorious for their harsh and intrusive methods. Unrestrained

by legal niceties, these secret police investigated every possible

revolutionary plot or subversive act, monitored literature (including that of

the great Russian poet Aleksandr Pushkin), and encouraged a network of

informers.

One of the "subversive" groups

monitored by the Third Department was the Petrashevsky Circle, a political

discussion group of gentry. Members of the group, including a promising young

writer named Fyodor Dostoyevsky, were arrested in 1849, sentenced to death

and, at the moment of their execution, had their sentences commuted and were

exiled to Siberia. This traumatic experience helps explain the dark

psychological nature of Dostoyevsky's novels, including his masterpieces Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov.

Aleksandr Pushkin, the leading Romantic poet

of the early nineteenth century, was treated much more leniently by the

authorities. Pushkin, a Russian nobleman whose grandfather was an African

courtier of Peter the Great, led a tempestuous life drinking, seducing women,

and dueling. Exiled to the Caucasus by

Aleksandr I for his unrestrained verse, Pushkin wrote several poems

influenced by this exotic locale, including The

Captive of the Caucasus and

The Fountain of

Bakhchissarai. He returned to St.

Petersburg in 1826 with Nicholas' approval and was

allowed to reside in the capital and continue his writing, but with the tsar

himself as the great poet's censor. Killed in a duel over his wife's honor at

age thirty-eight, Pushkin left a legacy of poetry, fiction, and literary

criticism. Ruslan and

Lyudmila, Boris Godunov, Eugene Onegin, and The Bronze Horseman, a

rumination on St. Petersburg

and its founder, are among his most famous works. Russians of all ages revere

him as their country's greatest national poet.

Russian thought in the first half of the

nineteenth century was strongly influenced by French and German Romanticism.

Some Russian Romantics, particularly the Slavophiles, echoed the German

philosopher Hegel's idea of the historical evolution of the human spirit. The

infusion of these ideas, together with Russia's

expanding imperial presence, stimulated a modern spirit of nationalism and

the conviction that Russia

possessed a unique mission. As Nikolai Gogol proudly remarks in the

conclusion of his novel Dead

Souls, "[A]rt thou not, my Russia, soaring along even like a

spirited, never-to-be-outdistanced troika? The road actually smokes under

thee, the bridges thunder . . . all things on earth fly past, and eyeing it

askance, all the other peoples and nations stand aside and give it the right

of way."

Russia's intellectuals,

however, were divided on what that destiny should be. From this mix of

intellectual fermentation and political repression, two broad currents of

thought emerged--those of the Slavophiles and the Westernizers. One of the

most prominent Westernizers was Peter Chaadaev ( 1793-1856), who was linked

to the Decembrists and who, in a series of letters published in the journal Telescope, criticized Russian

history for contributing nothing to modern civilization. The government

accused Chaadaev of insanity, the same tactic the Soviet regime would later

use against dissidents. However, other Westernizers, including T. N.

Granovskii and Vissarion Belinskii, continued to criticize Russian Orthodoxy,

advocated improving education and enacting a constitutional form of

government, and stressed the importance of individual freedom, science, and

rationalism.

The Slavophiles, led by K. Aksakov and A.

Khomiakov, rejected much of the Western influence that Peter the Great had

introduced to Russia.

For the Slavophiles, the common Russian people, the narod, possessed a pure and

simple spirituality far superior to the West's cold, scientific,

materialistic worldview. For Russia,

absolute monarchy, guided by the moral strictures of Russian Orthodox

Christianity, was the proper form of government. Constitutional democracy and

individual freedom were concepts alien to the Russian experience and could

only harm the nation. Russia

would surmount its troubles when the tsar managed to break down the barriers

between government and people that had been erected with the slavish adoption

of Western practices over the last century.

Nicholas I, unwilling to tolerate criticism

or independent thinking of any sort, harassed and repressed both the

Slavophiles and the Westernizers. In the later years of his reign Nicholas

became increasingly reactionary. Education was restricted in order to

discourage hopes of rising above one's position in the social order. Nicholas

was determined to defend the old order of monarchy and hierarchy and to

resist the gathering pressures for reform and republicanism within his own

country and throughout Europe.

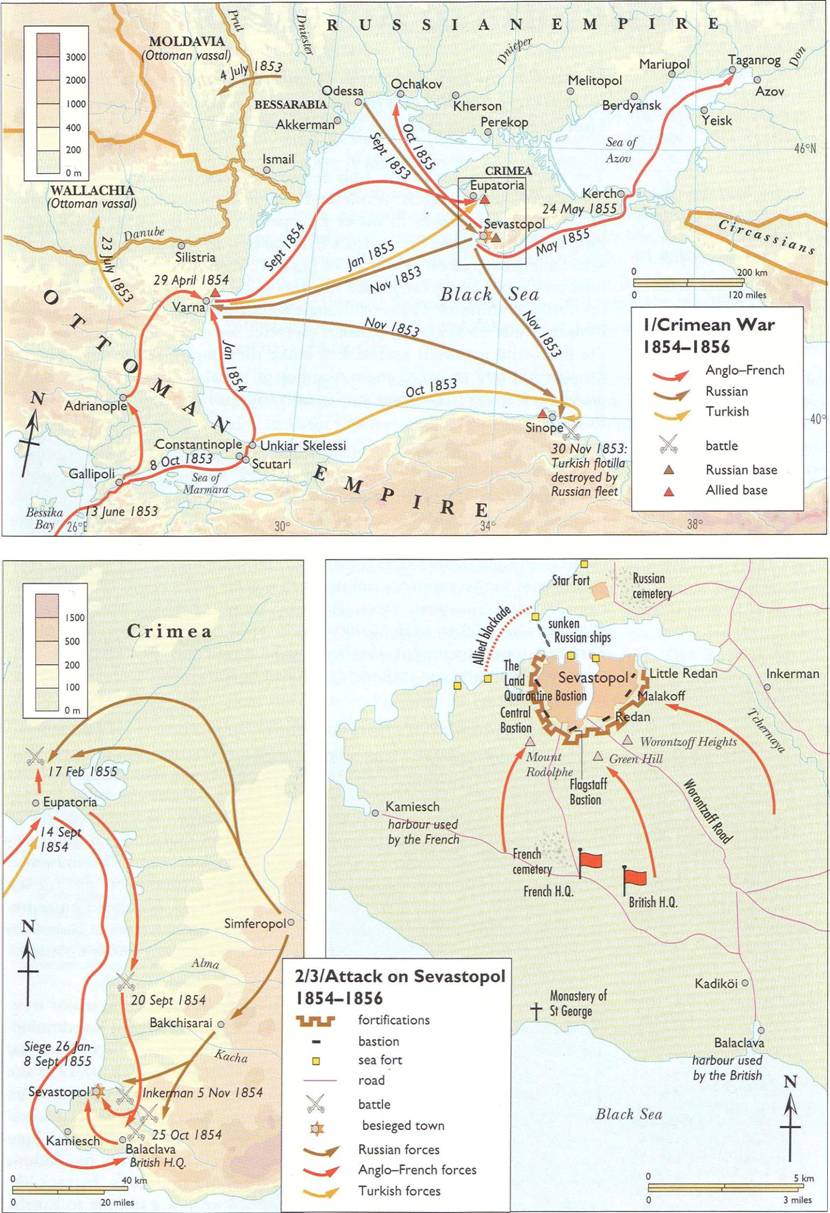

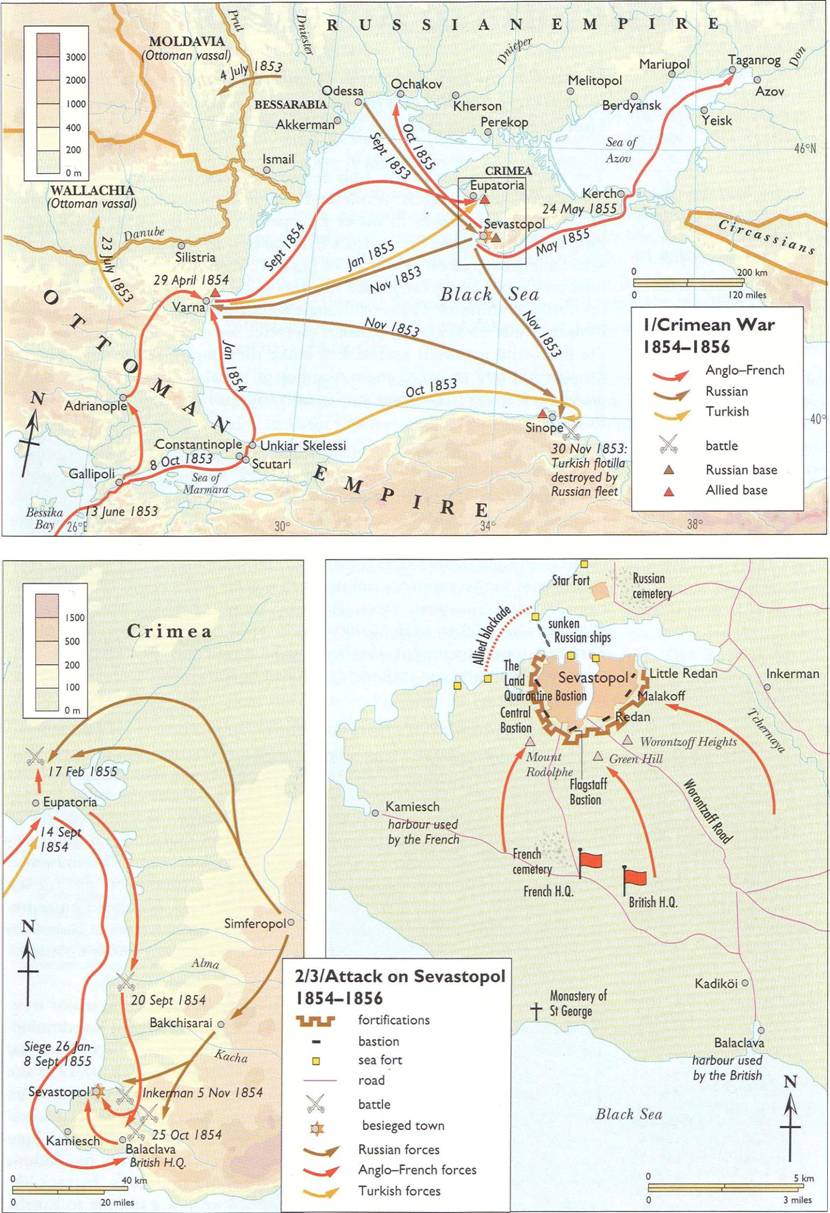

THE CRIMEAN WAR

The Crimean War, fought in the final years

of Nicholas I, shattered Russia's

confidence in its military and diplomatic capabilities and underscored the need

for social reform after three decades of reactionary government. The causes

of the war are complex. A dispute between Orthodox Christians and Catholics

over access to sites in the Holy Land led Nicholas to demand that Turkey, which

controlled the region, guarantee the rights of Orthodox believers.

Negotiations collapsed, and war between the two powers began in October 1853.

Great Britain, France, and Sardinia joined Turkey in the conflict on the peninsula, while

Austria, formerly Russia's ally, threatened in Moldavia and Wallachia.

Much of the fighting centered around the

Russian naval base of Sevastopol, on the west coast of the peninsula, which

was besieged by allied forces. The British poet Alfred Lord Tennyson conveyed

much of the senselessness of the fighting in his poem "Charge of the Light

Brigade."Nicholas died in March 1855 and was succeeded by his son,

Alek sandr II. After nearly a year of

bombardment Russian forces abandoned Sevastopol

in September. In March of the following year the Treaty of Paris was signed.

The terms were not especially onerous. Russia

ceded part of Bessarabia and the mouth of the Danube to Turkey, agreed that the Black Sea would be a

neutral body of water, and gave up claims to serve as protector of the

Orthodox in the Ottoman empire. Russia's role as the defender of monarchy and

reaction in Europe, so resolutely cultivated

by Nicholas I, had suffered a major setback. Fundamental reform, which

Nicholas had resolutely opposed for three decades, was now judged to be

critical for Russia's

future.

CHARLES E. ZIEGLER is Professor and Chair of

the Political Science Department at the University of Louisville.

He is the author of Foreign

Policy and East Asia (

1993), Environmental Policy

in the USSR ( 1987), and

dozens of scholarly articles and book chapters.

|

|