|

|

3

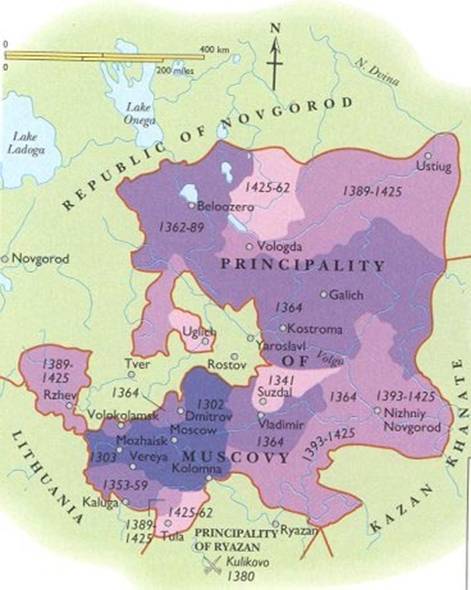

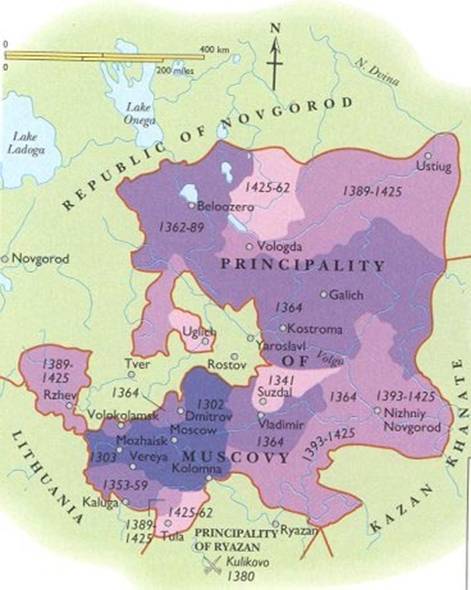

Muscovite Russia, 1240-1613

Moscow itself is great: I take the whole town

to be greater than London

with the suburbs: but it is very rude, and stands without all order. Their

houses are all of timber, very dangerous for fire. There is a fair castle,

the walls whereof are brick, and very high: they say they are eighteen feet

thick. . . . The Emperor lies in the castle, wherein are nine fair Churches,

and therein are religious men. . . . The poor are very innumerable, and live

most miserably. . . . In my opinion, there are no such people under the sun

for their hardness of living.

Captain

Richard Chancellor, English explorer and trader, 1553

POLITICS AND EXPANSION

In

comparison with the major cities of Kievan and appanage Russia, Moscow

in the twelfth century was merely a small and obscure town. Moscow

was not even mentioned in the chronicles until 1147, when Iurii Dolgorukii,

prince of Novgorod,

reputedly established the town as a commercial and strategic center. The

evolution of Moscow

from a pro- vincial town to the capital of a unified, centralized state is

the result of several factors--the impact of Mongol conquest and rule,

favorable geographic location, and in part luck.

Moscow's

rise to preeminence in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries involved

cultivating favor with the Golden Horde, the Mongol tribe that ruled Russia from Sarai, while struggling for

supremacy with the larger northern cities--most notably Tver and Novgorod. Daniel, the

youngest son of Aleksandr Nevskii, became the ruler of Moscow in 1263, and the city was granted

the status of a separate principality. Daniel enlarged Moscow

and expanded his authority along the length of the Moscow River.

After Daniel's death in 1303, his son Iurii Danilovich ( 1303- 1325) annexed

Mozhaisk in the east and contested with Prince Michael of Tver for control of

Vladimir and Novgorod.

The Golden Horde supported

Iurii in this struggle, granting him the title of Grand Prince and conferring

on him the right to extract tribute from all the northeastern towns. Iurii,

like his grandfather, Aleksandr Nevskii, owed his strong position in Novgorod to a businesslike

acceptance of Mongol suzerainty. The Mongols, in turn, supported Moscow in the struggle against its major Russian

rival--Tver--and against powerful Lithuania and the Teutonic Knights.

Novgorod's

elite also contributed to Moscow's

rise through their tendency to engage in self-destructive feuding. This

ancient city's institutions, as we saw in Chapter 2, embodied some partially

democratic ideas, most notably through the veche,

and a strong tradition of independence. Admirable as these traits might be

from a twentieth-century perspective, in the climate of intrigue and

factional struggle of the fourteenth century they combined to weaken Novgorod's chances for dominating post-Kievan Russia.

In the first century after

the Mongol invasion, Moscow

benefited greatly from its location. Shielded in the forested north, the city

avoided periodic Mongol raids that threatened southern Russian cities. Moscow's location at

the intersection of several major trade routes facilitated its development. Moscow also enjoyed

Mongol support against its powerful neighbors. After about 1350, however, Moscow had become

sufficiently powerful to challenge declining Mongol authority.

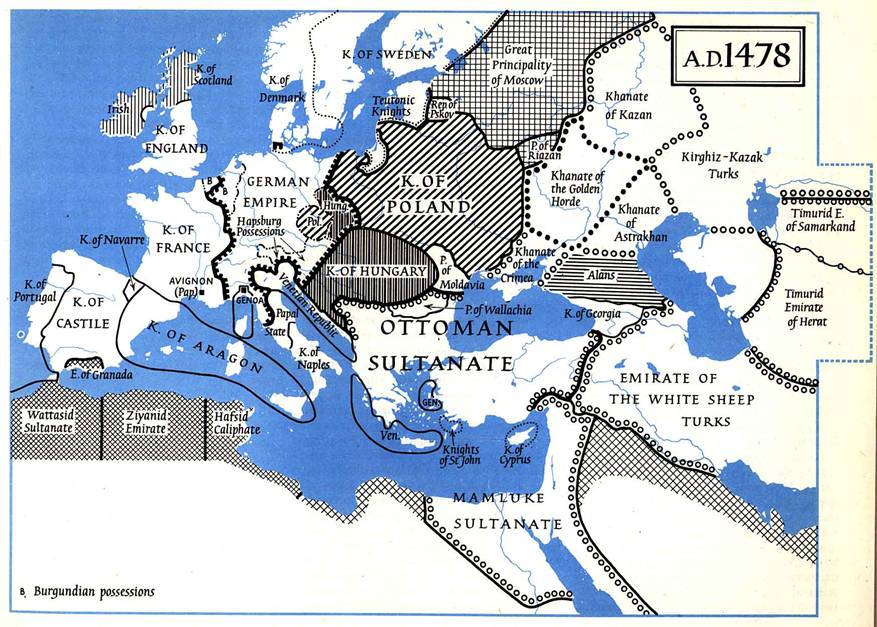

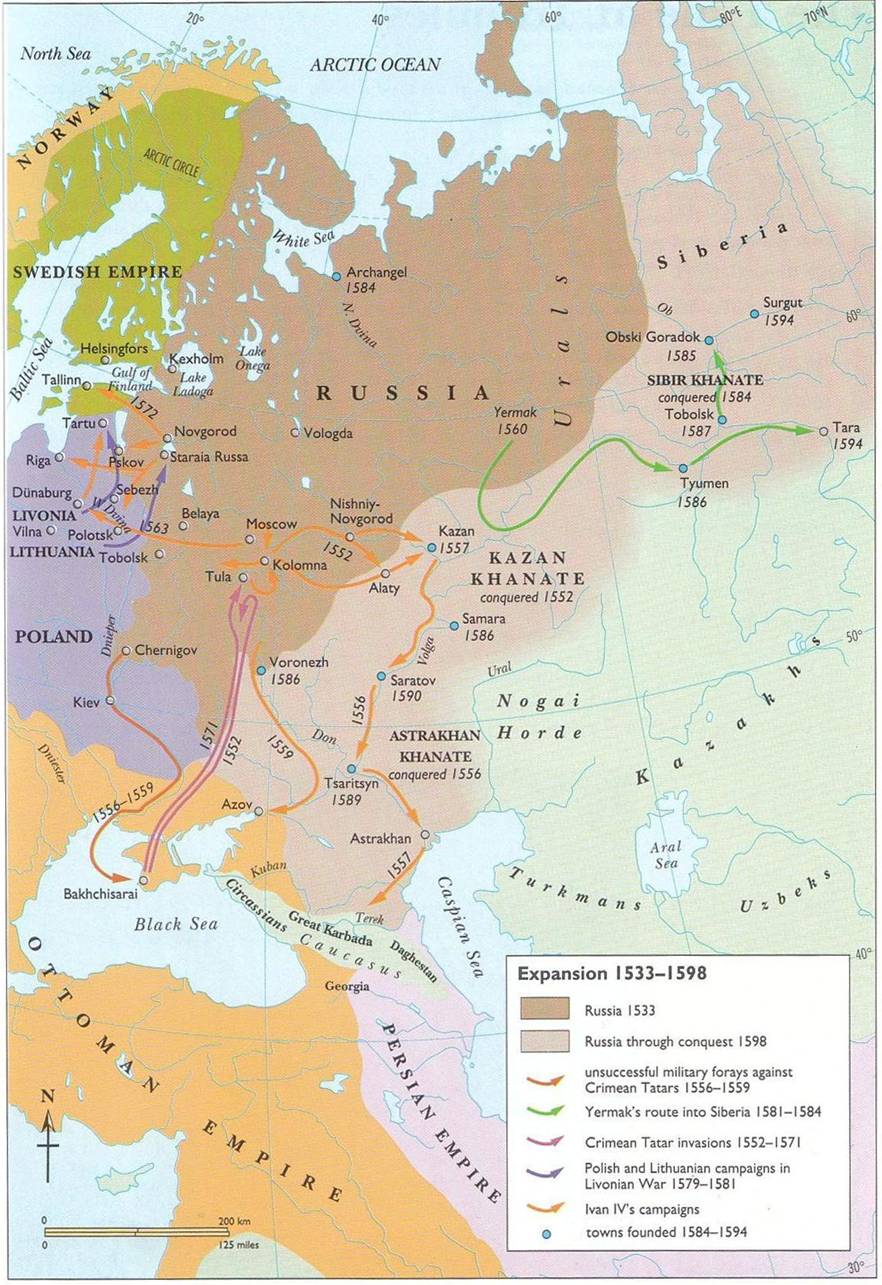

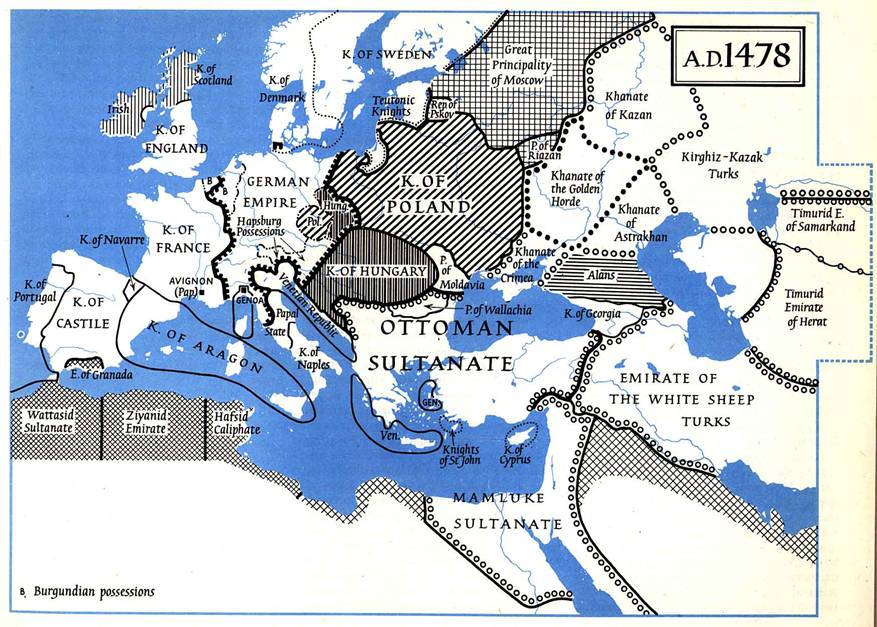

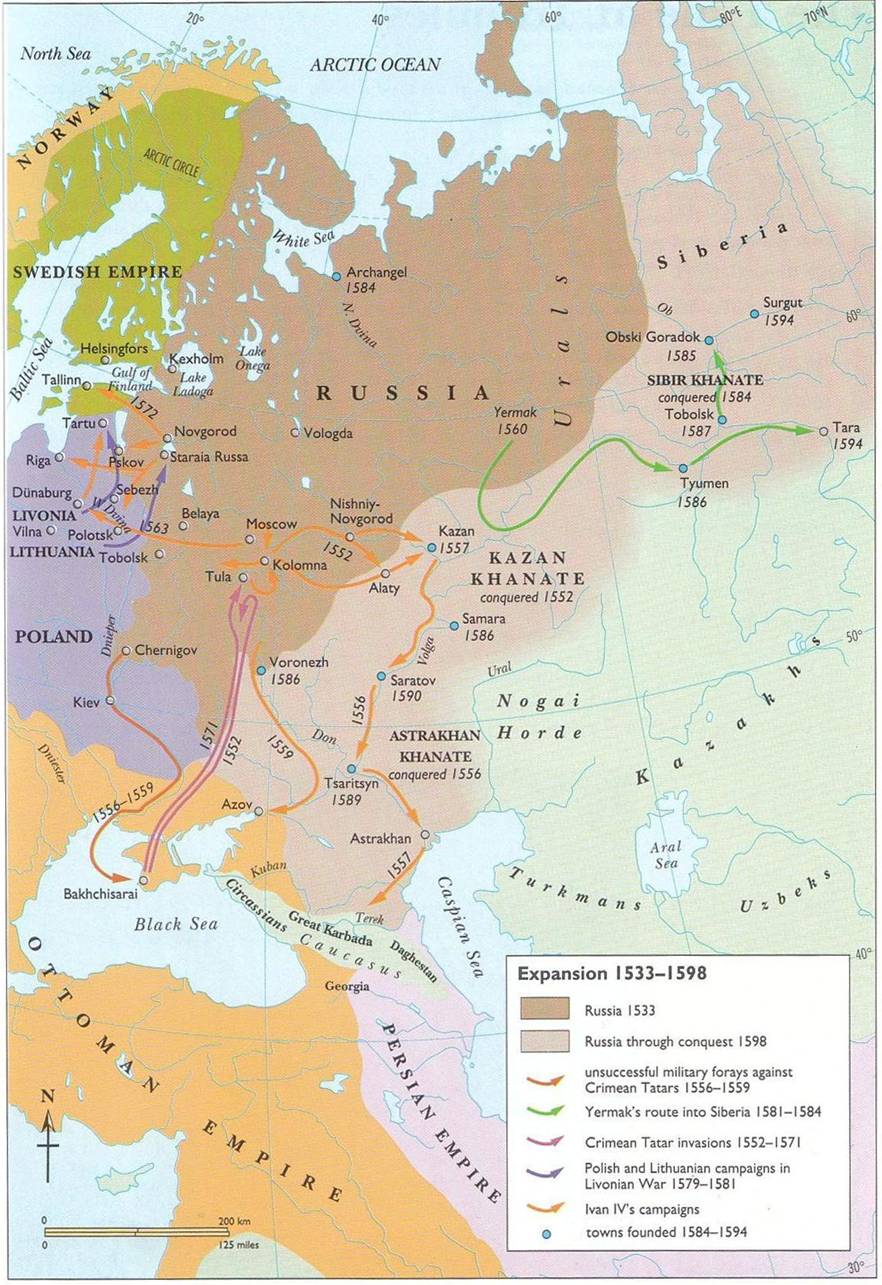

Late mediaeval Moscovy

Russia, Europe and the Near East (click on the map for better resolution)

Moscow's

power was greatly enhanced when the city assumed Kiev's former role as the center of Russian

Orthodoxy. The city of Vladimir

hosted the metropolitan, or head of the Orthodox Church, after 1300.

Metropolitan Peter ( 1308-1326) was not on the best terms with Prince Michael

of Tver, who had supported another candidate to lead the Or thodox Church.

Peter developed close ties with Prince Iurii of Moscow and, after his death in 1325, with

Prince Ivan I (Kalita, or "Moneybag"). When Peter died, he was

buried in Moscow; his successor, a Greek

bishop named Theognostus, assessed Tver's eroding position and decided to

shift his permanent residence to Moscow.

Theognostus ardently

supported Ivan's efforts to unify Russian lands under Moscow's control. Ivan deliberately

ingratiated himself with the Golden Horde by serving as an effective tax

collector. By collecting tribute from the other Russian princes he

strengthened his political position and amassed enough revenue to purchase a

number of appanages, substantially expanding the territory under Moscow's control.

By the middle of the

fourteenth century, Mongol power was declining, while that of Lithuania

to the west was growing under the Jagellonian dynasty. A crucial event marking Russia's

challenge to Mongol authority was the Battle of Kulikovo Field, in 1380.

Grand Prince Dmitrii Donskoi ( 1359-1389), aided by the farsighted

Metropolitan Alexis, unified Russia's

princes against the Lithuanian threat. Mongol unity had been undermined by

division into the khanates (roughly, principalities) of Kazan,

Astrakhan, and Crimea, and by the struggle

between Tokhtamysh (representing the Central Asian warlord Tamerlane) and

Mamai, Prince of the Horde, for control of Russia. Russia had

taken advantage of the opportunity this provided to challenge the Horde's

right to rule and collect tribute. In response, Mamai concluded an alliance

with Lithuania and engaged

the Russians in battle at Kulikovo, on the upper reaches of the Don River. Dmitrii, whose cause was reputedly endorsed

by the Abbot Sergius, moved before the Lithuanians could reach Mamai and

inflicted a surprising defeat on the Mongols.

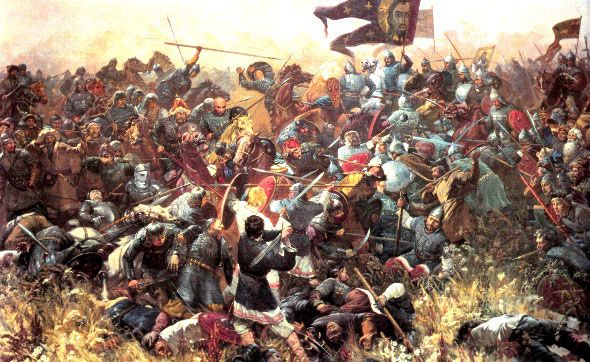

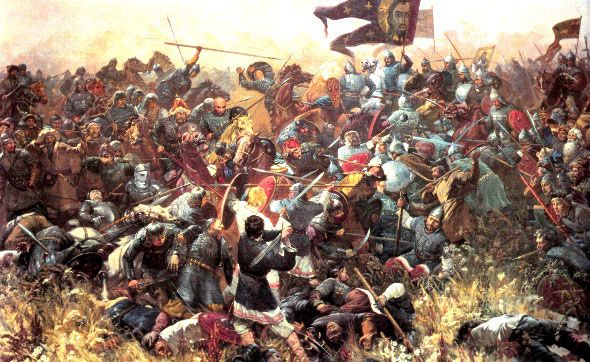

The Battle

of Kulikovo

The Battle of Kulikovo Field

destroyed the myth of Mongol invincibility and strengthened Russia's national awakening. No

matter that Mamai would return to sack Moscow

a mere two years later. As the Mongol rulers continued to war among

themselves, the Golden Horde's control over Russia waned. Tamerlane (Timur

the Lame), a ruthless warrior from Central Asia, further eroded Mongol power

by destroying many of their largest cities and repeatedly defeating

Tokhtamysh, the Mongol chieftain who had himself beaten Mamai for supremacy.

Tamerlane's destructive campaign played a significant role in weakening the

Golden Horde. By the middle of the fifteenth century the once-powerful Mongol

empire had been reduced to a scattering of small khanates along the lower

Volga, in Kazan, Astrakhan,

and the Crimea.

Vasilii II ( 1425- 1462)

ruled Moscow

during a period of constant civil strife and repeated Tatar incursions. Lithuania threatened Moscow from the west, while in the east the

fragmentation of the Golden Horde enabled Vasilii II to consolidate his power

and eliminate virtually all the surviving Russian appanages by 1456. His

predecessor, Vasilii I ( 13891425), had taken advantage of Mongol disunity to

annex NizhniiNovgorod, several hundred miles east of Moscow. Vasilii II defeated his chief

rival, Dmitrii Shemiaka, in ancient Novgorod,

ensuring that city's subordination to Moscow's

authority. In 1452 Moscow

extended its rule over the Tatar khanate of Kasimov, and the same year ceased

paying tribute to the Golden Horde.

An event of equal

significance for Muscovite Russia was the fall of Constantinople

to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. As we have seen, Byzantium's

cultural, political, economic, and religious influence on Russia had

been enormous. However, Russia's

ties to Byzantium

had been eroded by the Mongol conquest and the growth of the northern trade

routes. Byzantine influence on Russia had peaked between the

eleventh and fourteenth centuries, and declined thereafter. Under threat from

the Muslim Turks, the Greek Orthodox Church at the 1439 Council of Florence

recognized the supremacy of the Roman pope, antagonizing Russia's

Orthodox hierarchy. This "betrayal" by the Greek church, and the

subsequent "punishment" in the form of Turkish conquest, convinced

many Russians that they were left as the sole defenders of true Christianity.

In the sixteenth century this conviction would find expression in the

doctrine of Moscow as the third and final Rome. These

developments enhanced Russia's

sense of its uniqueness and its isolation from the mainstream of European

culture, and contributed to Russian xenophobia.

Ivan III

Ivan III ( The Great, 1462- 1505)

continued the process of "gathering together" the Russian lands,

expanding and centralizing the Muscovite state and effectively ending the

appanage period. When Tver concluded an alliance with Lithuania in 1485, Ivan invaded the

principality and incorporated it into Muscovy.

Ivan attacked Tatar Kazan in the 1460s, incorporated Novgorod

under Moscow's

control in the 1470s, and invaded Tver in 1485.

Soldiers of Moscow (left) and Novgorod

(right) / Modern miniatures by Oleg Gubarev

Ivan III used the vast lands

acquired through his conquests as rewards, forming a centralized, loyal

contingent of army officers among the upper classes to whom he granted

estates. He deported Novgorod

landowners, redistributing their lands to his supporters on condition that

they serve in his military campaigns. This system, called pomest'e, assured the grand

prince of a loyal and dependent cavalry and curtailed the military resources

available to the remaining appanage princes.

Governing and defending an

enlarged Russia

required the creation of a small bureaucracy and more professional armed

forces. Ivan III appointed governors and district chiefs to administer Russia's new territories, arranging for them

to provide Moscow

with revenue, most of which went to support the army, through a system of

"feeding" (kormlenie). The feeding system both enhanced the

independent authority of regional governors and, since they were allowed to

keep a surplus of what they collected, also encouraged corruption. A national

law code enacted in 1497, the first Sudebnik,

standardized judicial authority,

restrained administrative abuses, limited peasant mobility, and helped in

tegrate an expansive Moscow.

Vasilii

III ( 1505- 1533) continued the process of consolidation, expansion, and

centralization pursued by his father. Pskov

was annexed in 1510 and its veche bell taken down; Riazan was

incorporated into the Muscovite empire in 1517. The owners of large estates

in these former appanages were deported, and their lands were redistributed

to Vasilii's servitors. Vasilii III was a strong ruler, yet he consulted

regularly with the boyars in the Duma.

Muscovite

Russia developed an imperial and national ideology, bolstered by Russian

Orthodoxy, during the reigns of Ivan III and Vasilii III. Both rulers

occasionally used the title tsar (or caesar), implying sovereign

authority and the rejection of subordination either to the Mongols or to Byzantium. With the

fall of Constantinople, the seat of Greek Orthodox Christianity, to the

Muslim Turks in 1453, Russians increasingly thought of Moscow as the last citadel of

"genuine" Christianity. A letter from Abbot Filofei to Vasilii III

in 1510 drew on biblical references to enunciate the doctrine of Moscow as the Third

Rome: "two Romes have fallen, the Third stands, and there shall be no

Fourth." This doctrine legitimized Russia's imperial expansion and

the divine right of Russian autocracy.

The concept of Russia's divine mission as the center

of Christianity and the role of the tsar as God's direct representative on

earth were further elaborated during the long reign of Ivan IV ( 1533- 1584),

who is better known in the West as Ivan the Terrible. Ivan IV, who succeeded

to the throne at age three, witnessed bitter factional fighting among the

boyar families before he formally assumed the crown in 1547. Terrified by a

massive fire that consumed much of Moscow

later that year, and convinced God was punishing him for his transgressions,

the young tsar formed a Chosen Council of nobles and church leaders to serve

as an advisory body. In order to enhance public support Ivan IV consulted openly

with Moscow's

elites, calling the first full zemskii

sobor ("assembly of

the land") in 1549. He issued a new law code ( Sudebnik) in 1550, to ensure

that the same laws were applied equally throughout the newly acquired

territories and to protect the lower gentry's interests against abuses by

regional governors. Ivan Sudebnik reflected the growing division of

Russian society according to rank and position.

Ivan

IV

Ivan IV also created a series

of central chanceries to run Moscow's

growing bureaucracy and to provide more efficient mobilization of resources

for war. Finally, in 1551 Ivan and the priest Sylvester, author of the Domostroi, a manual for governing upper-class

households, imposed a series of reforms on the Orthodox Church entitled the Stoglav (Hundred Chapters). The Stoglavsought to control the

Church's accumulation of wealth, criticized corrupt monastic practices,

proscribed a number of pastimes as indecent (including chess, playing the

trumpet, and enjoying pets), condemned shaving one's beard as a heretic

Catholic practice, and prescribed certain modifications in church rituals.

The Stoglav and Domostroi infused religious content into

virtually all aspects of sixteenthcentury Russian life by condemning secular

pursuits as frivolous or sinful.

The

central thrust of Ivan IV's rule was to consolidate and strengthen

centralized rule, which meant weakening the influence of the top boyar

families. Ivan was extremely suspicious of the boyars, in part due to his

experiences as a child and in part as a result of the unseemly political

maneuvering during his grave illness in 1553. Angered by Ivan's capricious

rule and dismayed by Russia's poor performance in the Livonian War of

1558-1582 (fought to expand Russia's territory westward and secure access to

the Baltic Sea), a number of the boyars had defected to Lithuania, Livonia,

or Poland. Among the disaffected boyars was Prince Andrei Kurbsky, a literate

man whose vitriolic correspondence with the tsar has given scholars a record

of the clash between Ivan IV and the upper classes.

Late

in 1564 Ivan IV took a calculated risk designed to enhance his power. Taking

a large retinue, he left Moscow

for a small settlement in the northeast, Aleksandrovskaya Sloboda, from which

he announced his intention to abdicate. Thrown into consternation, the tsar's

followers begged him to return to Moscow

and resume his office. Ivan IV agreed, but with certain conditions. Ivan

demanded complete autonomy, including freedom from the moral strictures of

the Church, to punish traitors as he saw fit.

To

carry out his revenge against the treacherous boyars, Ivan divided Russia into

two separate states. Within the oprichnina,

consisting of some two dozen cities, eighteen districts, and part of Moscow, the tsar

exercised total power. In the remainder of Russia, the zemshchina, direct rule

theoretically would be exercised by the boyar Duma. However, Ivan created a

loyal militia, the oprichniki,

to wage a form of civil war against nobles and property owners in the zemshchina. The fearsome oprichniki, some 6,000

strong, dressed in black and carried a dog's head and broom on their horses

to symbolize their mission of hunting down and sweeping away the tsar's

enemies. Ivan used the oprichniki to arrest, torture, imprison, and

execute any of the nobility, the clergy, their families, and supporters whom

he imagined posed a threat to his rule.

For seven years Ivan IV

carried on a vendetta against his own people. Early in 1570 Ivan led his oprichniki against the city of Novgorod, whose inhabitants once had the

temerity to call their town "Lord Novgorod the Great." Apparently

infuriated by the city's refusal to submit abjectly to his authority, Ivan

spent five weeks torturing, raping, and slaughtering his subjects. In all he

is estimated to have massacred between 15,000 and 60,000 people, or about

three-fourths of the population. After Novgorod,

Ivan set out to destroy the city of Pskov.

However, one of the so-called holy fools of Pskov, the monk Nicholas, threatened Ivan

the Terrible with heavenly destruction should he harm the city. Frightened,

Ivan withdrew to Moscow, and Pskov was spared. Two years later he

executed most of the leaders of the oprichniki,

bringing an end to this bloody period of Russian history.

Although Ivan IV adhered to

the rites of the Russian Orthodox Church and considered himself God's representative

on earth, by the time of the oprichnina he had rejected the Church's

traditional role as moral conscience of the tsar. Those religious authorities

who tried to remonstrate with the tsar--the Metropolitan Philip, for

example--were tortured, banished, or killed. The clergy had acted as a

restraining influence on the tsar during the early years of his reign; by the

latter part of his rule, however, he had terrified the Church hierarchy into

abjectly supporting his cruel tyranny. With the nobility and the clergy

completely broken, there were no checks on Ivan's despotic rule. All Russians

were the tsar's slaves.

From a modern Western

perspective it is difficult to imagine how a people would accept such a

cruel, debauched ruler as Ivan the Terrible. At one point he had a giant

skillet constructed in Red Square in which

his hapless enemies were roasted alive. Ivan also reveled in personally

torturing prisoners, often after attending mass or before retiring to one of

his wives or mistresses. Frequently, Ivan shared drunken orgies and torture

sessions with his older son, Ivan, in a type of medieval male bonding. The

two also enjoyed turning wild bears loose on unsuspecting Muscovite crowds

and watching the fun.

The Russian people were

terrified of their tsar, but few contemplated any sort of uprising against

him. Some, like Prince Kurbsky, condemned him from afar. The few who were

courageous enough to oppose his bloody methods and remain in Russia did

not generally survive. One must recognize that a dominant strain in Russian

Orthodoxy was the theme of achieving spiritual rewards through suffering. The

tsar, the earthly king, was no less justified in visiting calamities on his

people than was God the heavenly king. The decisions of both were likely a

just punishment for their transgressions, and in any case could not be

questioned or even understood by most Russians.

The last years of Ivan's

reign were marked by foreign policy adventures and domestic failures. In the

1550s Ivan's forces had subjugated the Tatars of the Kazan

and Astrakhan khanates, to the east and south,

ending the raids that had threatened Moscow

periodically. To celebrate his victory over the Kazan

khanate, Ivan commissioned the construction of the famous St. Basil's

Cathedral, in Moscow's Red

Square. Toward the end of Ivan's reign the Cossack Ermak

conquered the Kuchum khanate in western Siberia, the first step in an

extended process of expansion eastward to the Pacific Ocean and eventually

into North America.

Moscovy Russian

expansion under Ivan the Terrible

Ivan the Terrible's successes

in dealing with the Muslim Tatars in the east were more than offset by his

failures in the wars with his Christian neighbors to the west. In 1558 Ivan,

determined to expand Muscovy's frontiers to the Baltic Sea, and thereby

enhance Russian commerce, launched the war against Livonia

in what is now Latvia and Estonia. By

1560, the year his beloved first wife Anastasia died, Ivan's initial successes

were reversed with the entry of Lithuania,

Poland, and Sweden into the war against Russia. The

Livonian War dragged on for twenty five years, draining the Muscovite

treasury, dividing the court, and feeding Ivan's paranoia and his obsession

with traitors.

Ivan's cruelty and depravity

reached their apogee when, in a fit of rage, he struck and killed his eldest

son with the iron-tipped staff he always carried. This poignant moment,

captured in a famous painting by the nineteenth-century artist Ilya Repin,

signaled the close of Ivan's bloody regime. Following his death in 1584 his

son Feodor ascended the throne. However, Feodor was weak and incompetent, and

could not manage the legacy of war and internal

division bequeathed him by his father. Russia was soon immersed in the

chaos of dynastic struggle and civil war referred to as the "Time of

Troubles," which lasted until the establishment of the Romanov dynasty

in 1613.

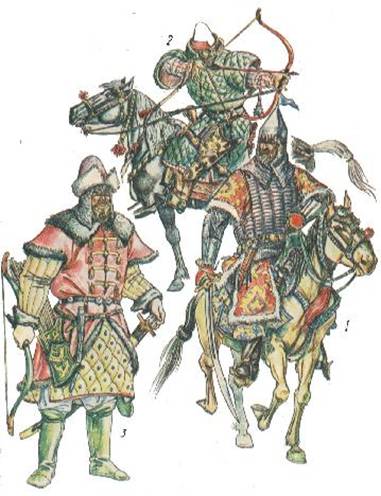

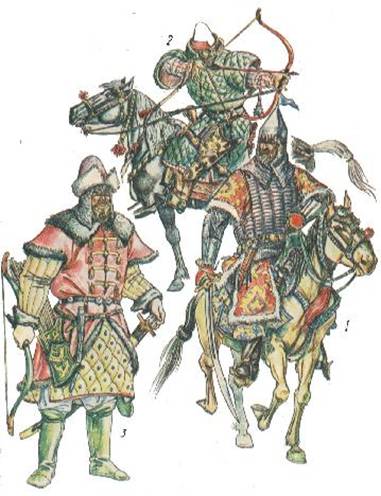

Soldiers of Ivan

the Terrible

RELIGION AND CULTURE

Religion was by far the

dominant influence in medieval Russian culture. The Orthodox Church mobilized

Russian national identity, legitimized political authority, molded social

relations, dominated literature and architecture, and controlled a

significant share of the economy. At the beginning of the sixteenth century,

for example, the Church owned between one-quarter and one-third of Russia's

arable land.

Russian church architecture

had recovered by the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Vassilii

II and Ivan III undertook huge construction programs, using Italian and later

German and Dutch builders. The great Moscow Kremlin ("fortress")

was reconstructed in the fifteenth century; most of the cathedrals housed

within the Kremlin were built at this time. In 1552 Ivan IV had St. Basil's

Cathedral constructed on the edge of what is now Red Square, to commemorate

his victory over the Tatar khanate in Kazan.

Based on the pattern of Russian wooden churches, St. Basil's, the

quintessential backdrop for television reporting from Moscow, is a colorful group of nine

octagonal churches topped by golden cupolas and set on a single foundation.

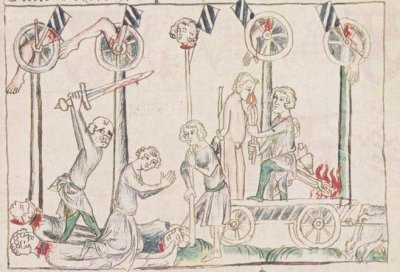

In the fifteenth century

several sects and divisions appeared in Russian religious life. There were

the Judaizers, not really Jews but rather Russian Christians who rejected

parts of the New Testament and certain teachings of the Orthodox Church. The strigolniki (shaved ones) also denied the

authority of the Church, criticizing it as corrupt, and sought individual

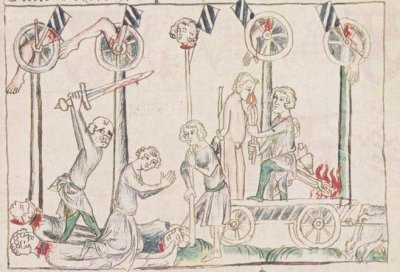

salvation through Buddhist-like contemplation. As in the Europe

of that time, such heretics were not easily tolerated by the dominant church,

and were frequently burned at the stake.

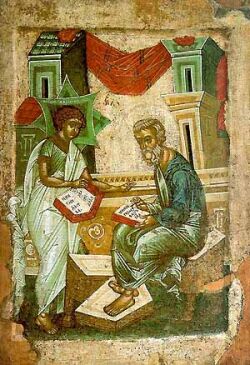

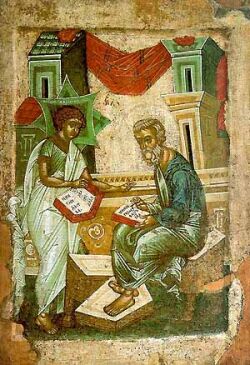

Russian icons of the 15th century

A major schism of the late

fifteenth century within the Orthodox Church was between the so-called

possessors and non-possessors. The non-possessors, led by Nil Sorskii,

insisted that the Church should renounce worldly wealth, monks should adhere

to vows of poverty, and church and state should be separate. However, a

Church council of 1503 supported the possessors, led by Joseph of Volotsk,

who advocated a rich, powerful Church glorified by the splendor of icons,

extensive land holdings, and impressive ritual. The possessors stressed the

importance of a close, harmonic relationship between Church and ruler, which

strengthened the concept of the divine right of the tsar.

Literature and art

represented religious themes almost exclusively during this period, in

contrast to the secular intellectual currents developing in Europe.

Medieval Russian literature, according to historian Victor Terras, was a

vehicle of religious devotion, ritual, and edification, written by monks, for

monks, about monks. Hagiographies, or saints' lives, were one of the most

common forms of literature. The purpose of these stories was to glorify God

and His loyal servants, and not to present accurate biographies. Similarly,

Russian chronicles, another prominent genre, mixed history with political

propaganda and morality tales. Among the more important of these were the Life of St. Sergius of Radonezh by Epiphanius , the story of the

founder of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery, and the Tale of the White Cowl of

Novgorod, which promoted the concept of Moscow as the Third Rome.

Religion was an important

influence in popular culture, although not through literature. Few Russians,

and virtually no members of the lower classes, knew how to read. Religious

icons and oral traditions substituted for the written word. Even modest

peasant huts (izby) reserved a corner for holy icons, which were

believed to protect the family from harm. However, peasants also preserved

some old Slavic pagan beliefs and customs, including offerings to the house

sprite (domovoi). They also retained certain marriage and funeral

practices dating from pre-Christian times. Popular entertainment included

Russian folk songs and folk tales, and the epic poems (byliny) that recounted

the exploits of heroes both ancient and contemporary.

ECONOMICS AND SOCIETY

The

Mongol invasion crushed the robust urban commercial life that had

characterized Kievan society. Many towns simply ceased to exist, others lost

much of their population, and Russians abandoned trade for a more insular,

self-sufficient agricultural life. Landowning became the major basis of

prosperity. Since the landlord's wealth depended on peasant labor, the

freedom of this class, some 70-80 percent of the population, to change their

place of residence was gradually curtailed. By the end of the fifteenth

century peasants were tied to the estate except for a two week period around St. George's Day,

November 26, when they could pack up and leave their masters. Ivan the

Terrible further curtailed the peasants' freedom of

movement. The institution of serfdom, tying peasants to the land permanently,

evolved gradually through the medieval period and was fully legalized by the

law code (Ulozhenie) of 1649 enacted under Tsar Alexis ( 1645- 1676).

The social classes of

medieval Russia

were not much different from those of Kievan Rus. At the top remained the

boyars, the handful of nobles who served as advisors to the grand prince.

Just below the boyars were the junior boyars (or boyars' children--boyarskie

deti) and the gentry. The higher clergy--the metropolitan, archbishops,

and influential priests and monks--were also part of the upper classes. Next

came merchants, followed by skilled urban artisans such as carpenters, boottnakers,

masons, and silversmiths.

Russian aristocratic woman

Most Westerners know about Russia's

Cossacks, who first appeared during this period, but few have an accurate

understanding of these colorful people. Cossacks were free peasants who

emerged in various frontier regions of Russia

and Ukraine, particularly Zaporozhe, Riazan, and

the Don region, during the mid-fifteenth century. At first resistant to Moscow's authority,

they gradually came to be loyal subjects of the tsar. Their lifestyle, based

on a steppe existence, was quite different from that of the forest-dwelling

Russians or Ukrainians. Cossacks lived by fishing, trapping, and plundering.

Largely Slavic, they also accepted Germans, Swedes, Tatars, Greeks, and other

adventurous types, as long as they were tough fighters and nominally

Christian. Although renowned for their horsemanship, the Cossacks were also

great sailors and fearsome pirates who periodically threatened trade on the Volga River

and the Black Sea.

Cossacks played a pivotal

role in medieval Russia,

as explorers and rebels. It was a Cossack, Ermak Timofeevich, who under

contract to the wealthy Stroganov family ventured across the Ural Mountains and attacked Khan Kuchum at his capital

of Sibir. By defeating the Siberian Tatars and their allies, various Siberian

tribes, Ermak opened the huge Siberian territory to Russian eastward

expansion. Although Ermak was eventually killed by the Tatars, other Cossacks

followed the massive Siberian rivers, reaching the Pacific

Ocean by the middle of the seventeenth century, in their search

for sable furs and walrus tusks. These intrepid explorers apparently crossed

the Bering Strait into Alaska

sometime before the eighteenth century.

Peasants, as noted above,

constituted the great majority of the population in medieval Russia. As a

whole, the peasants were illiterate, superstitious, and poor. They were

forced to work on the landlords' estates and were required to give their

master a large proportion of their produce or, in certain cases, payments in

cash. By the time of Ivan IV taxes on the peasantry, levied to pay for

frequent military campaigns, had become increasingly burdensome, leading many

to desert the estates and seek more favorable conditions in the south or

east.

At the lowest rung of the

social ladder were slaves, about 10 percent of the population. However,

Russian slavery, which continued into the eighteenth century, was quite

different from that in the United

States. First, there was no ethnic or

racial difference between slave and master. Second, slaves did not work in

agriculture, but were employed primarily as household servants. Third,

slavery was, as Richard Hellie has suggested, a form of social welfare for

medieval Russia.

Those free individuals who could not pay their debts or otherwise support

themselves might become slaves. The slave owners then assumed legal

obligations to clothe and feed their slaves and treat them humanely, and were

prohibited from freeing them during famines to avoid their obligations.

Finally, the male slaves who served as stewards for a rich household acquired

considerable authority and responsibility. These "elite" slaves

ranked above their ordinary counterparts in Muscovite society's hierarchy.

It is interesting to note

that while medieval Muscovy was far from a

tolerant society, the lines of division were based on class, gender, and

religion, not race or ethnicity. For example, the grand princes would often

recruit defeated Mongol princes for their court following a battle, provided

they converted to Orthodox Christianity. Ivan the Terrible took a Circassian

princess as his second wife, although she had to be baptized into the

Orthodox faith prior to the wedding. Church law, however, strictly prohibited

marrying across class lines; a free man who married a slave woman would

himself lose his freedom.

Medieval Russian society,

with its rigid hierarchy enforced by religious strictures, relegated women to

subordinate positions politically, economically, and socially. The Russian

Orthodox Church, like other Christian denominations, viewed women as

inherently sinful and a temptation to men, based on biblical teachings.

Accordingly, "good" women were quiet, submissive, and humble. Just

as men were supposed to be obedient to the tsar, women had to obey their

husbands in all matters. The Domostroi,

a set of rules for keeping a

well-ordered upper-class household published about 1556, instructs wives to

consult their husbands on every matter and to fulfill all their commands

diligently. If they dis obeyed, the wise husband would beat them

judiciously. However, the Domostroi also elaborates on the many

responsibilities of running a large household that rested with upper-class

women, including supervising the servants and raising the children.

To protect their status

within the patriarchal order, upper-class women in medieval Russia were

secluded in specific living quarters and prohibited from socializing with

men. They were also granted generous protections against any slights to their

honor. Women from the artisan, slave, or peasant classes had far fewer

restrictions on their social interactions. The economic demands on

lower-class families forced women to work alongside men in a variety of

occupations. Women were useful because they served important functions--they

worked, produced and raised children, and managed the household--not because

they were considered important in their own right. Nonetheless, even women of

lower social status were protected against rape, abuse, or insult by Russian

law of the time.

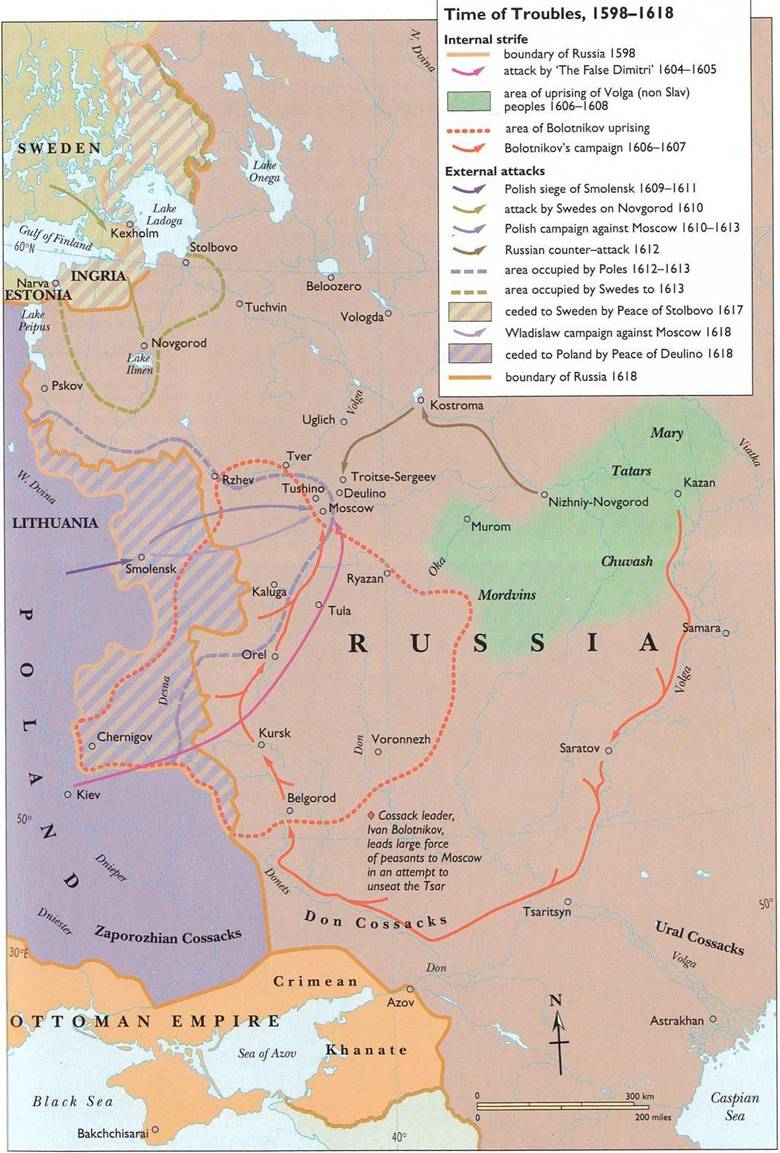

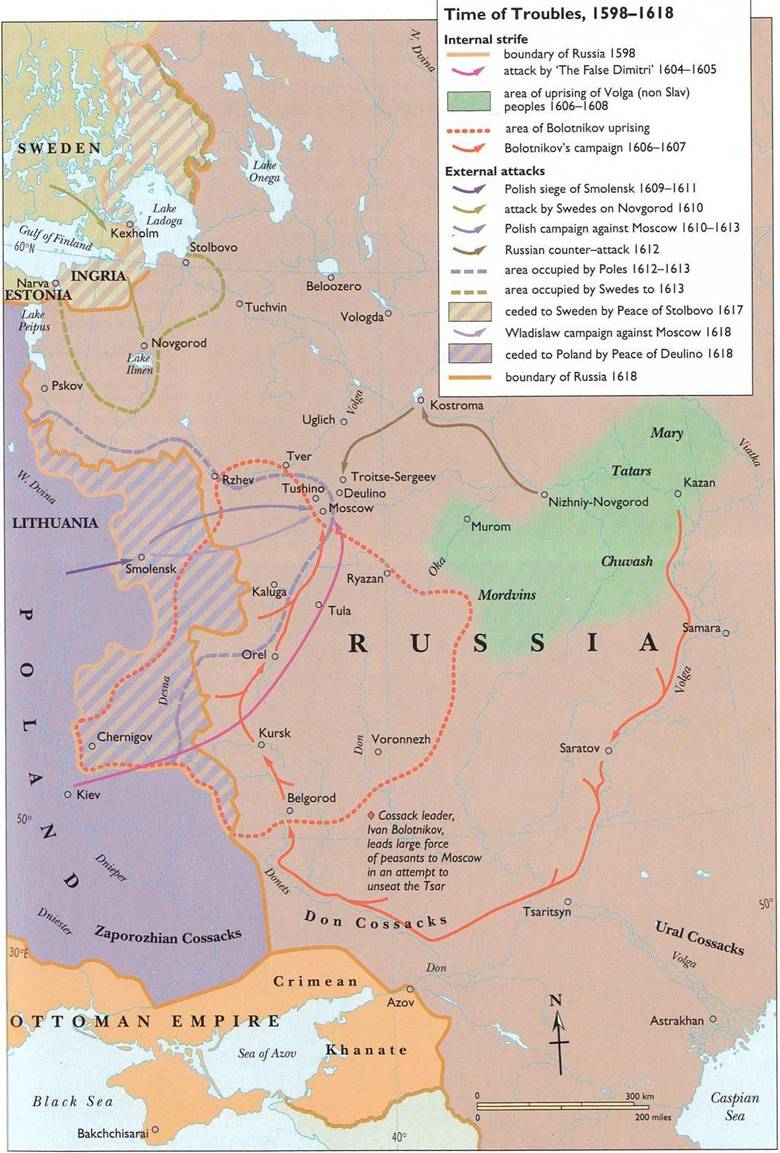

RUSSIA'S TIME OF TROUBLES (1584-1613)

When Ivan the Terrible died

in 1584 he left Muscovy with a mixed legacy.

Russia

was far larger and more powerful than at any time in the past; the Mongol

yoke had been broken, the state centralized, and all restraints on the tsar's

authority abolished. With the Turkish occupation of Constantinople, Moscow proclaimed

itself the center of Orthodox Christianity, the Third Rome. Western

influences in the form of traders and delegations from Germany, France,

and Britain, though not

always welcome, raised the level of technology in Russia, particularly in the

military sphere.

However, the protracted Livonian War, excessive

taxation, natural disasters, and Ivan's cruel exploitation of his own people

strained Russia

to the breaking point. The upper classes had suffered the loss of their

estates, exile, or worse during the oprichnina;

peasants had fled the central

provinces to avoid heavy taxes and further

restrictions on their freedom. After Ivan the Terrible died Russia was

once again consumed by dynastic struggles. The late tsar had killed his more

able son and heir Ivan Ivanovich in a fit of rage in 1581; hence it was the

weak and incompetent Feodor who ascended the throne in 1584. Within three

years, however, Boris Godunov, an astute and capable boyar, emerged as the

real power behind the throne. A younger son of Ivan IV, Dmitrii, died in 1591

under mysterious circumstances; unsubstantiated rumors suggested that Boris

Godunov was responsible. Feodor died in 1598 without an heir, and the

Riurikid dynasty finally came to an end.

In the chaos that followed, a zemskii sobor (assembly of the land) chose Boris

Godunov to succeed Feodor as tsar of Russia. Using a combination of

public works programs and state repression, Boris unsuccessfully sought to

stem Church and boyar opposition, peasant flight from the estates, and

Cossack rebellion. In the last years of Boris' reign a pretender to the

throne, a "false Dmitrii" claiming to be Ivan IV's son, organized

an opposition force of Poles, Ukrainians, and Cossacks. When Boris Godunov

died in 1605 the rebels took Moscow

and installed the pretender as Dmitrii I.

False Dmitrii and king Sigismund

III Vasa by Nikolai Nevrev (1874)

(Click here for more details)

Dmitrii's

Polish connections, particularly his marriage to the Catholic Marina Mniszech

and the presence of hundreds of Poles in Moscow, enraged Russians, and Dmitrii I was

murdered within a year. Prince Vasilii Shuiskii was installed as Vasilii IV (

1606- 1610), but he could not put an end to the civil strife and foreign

intervention that plagued Moscow.

Ivan Bolotnikov, a Don

Cossack, led a bloody uprising against the upper classes. Once this

revolt had been crushed a second False Dmitrii arose to challenge Vasilii IV,

and for two years Russia

endured another civil war. After years of turmoil, a large zemskii sobor convened in Moscow in 1613 to choose a new tsar. The

assembly selected Mikhail Romanov, a mere youth of sixteen but a member of

one of Moscow's

most distinguished families, as their sovereign. With the selection of Tsar

Mikhail, Russia's

Time of Troubles drew to a close. The Romanov dynasty would rule Russia

for the next three centuries, until its overthrow in the Revolution of 1917.

Mikhail Romanov (left)

and zemskii sobor of 1613 (right)

CHARLES E. ZIEGLER is Professor and Chair of the Political

Science Department at the University

of Louisville. He is

the author of Foreign Policy

and East Asia ( 1993), Environmental Policy in the USSR ( 1987), and dozens of scholarly

articles and book chapters.

|

|