|

|

Introduction

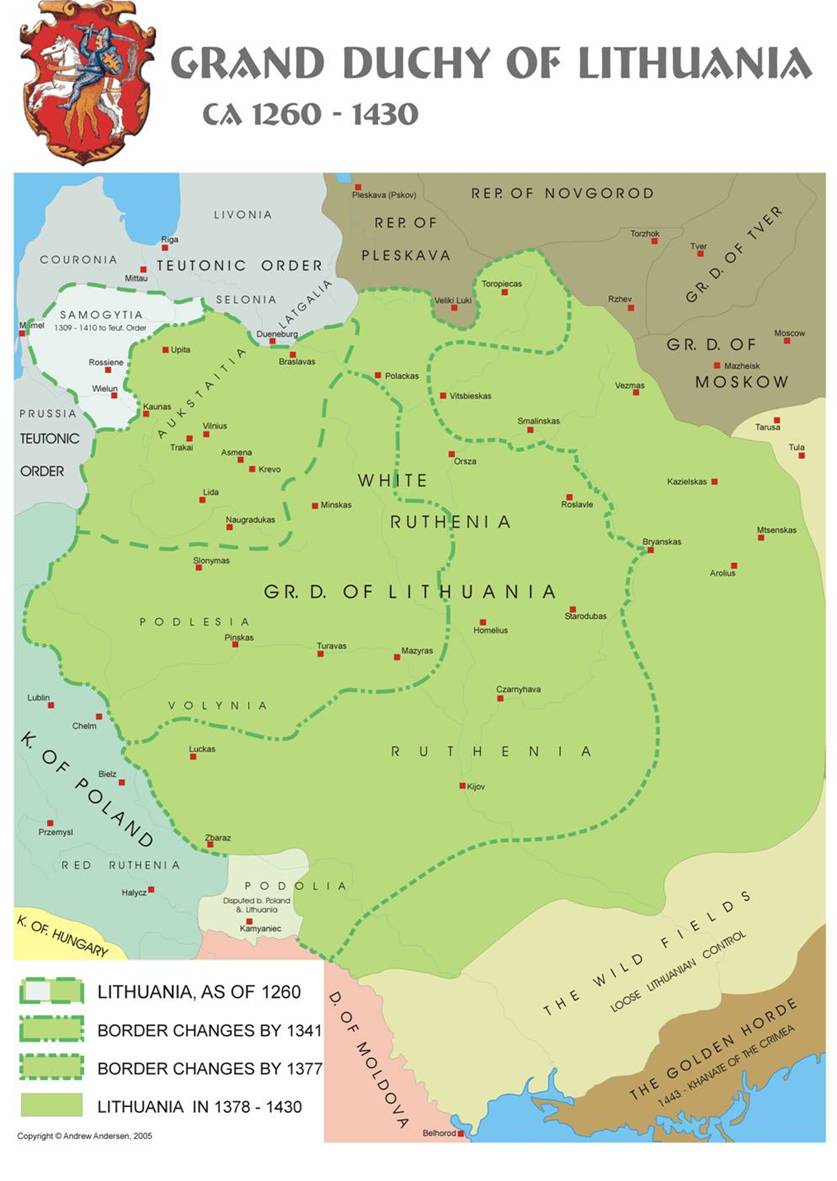

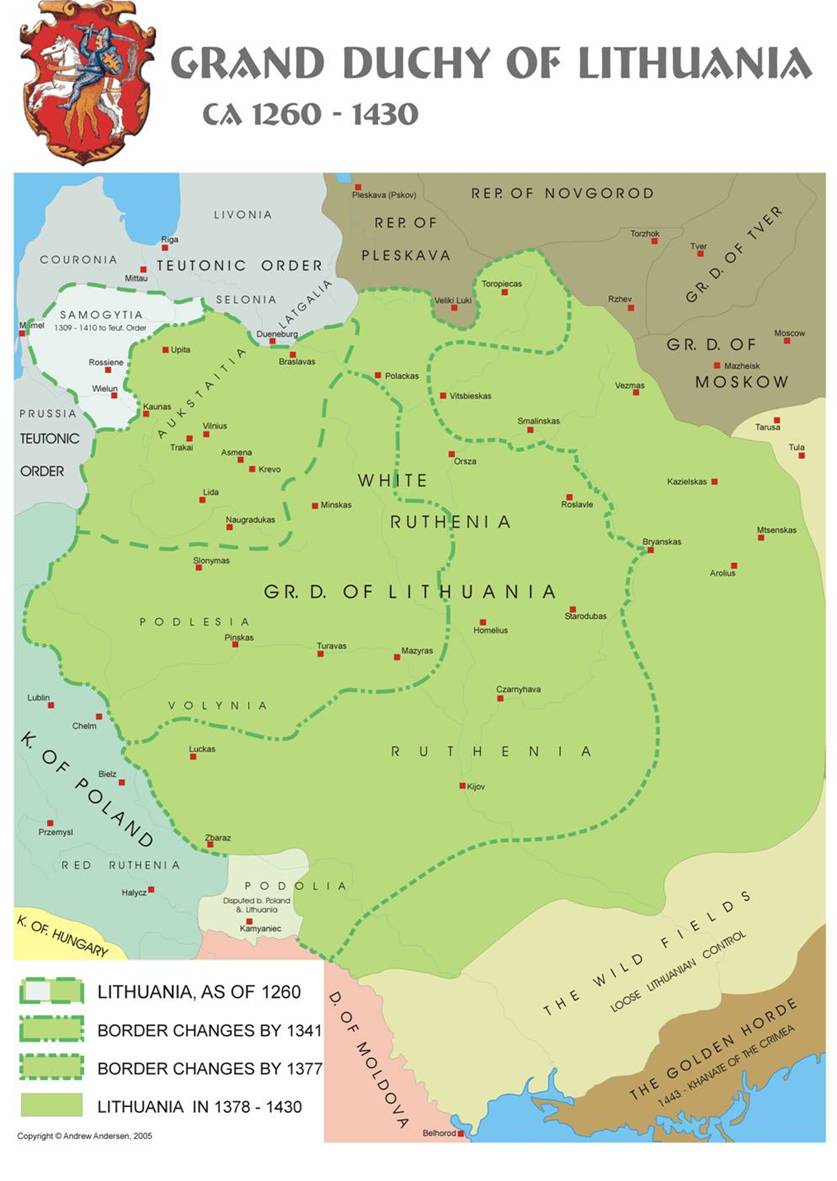

Although the independent nation of

Lithuania has only

relatively recently appeared on maps of Eastern Europe,

it is preceded by a lengthy and significant history. Modern Lithuanian

territory is but a fraction of the vast expanse which once included

present-day Ukraine, Belarus and Poland

(as part of a unified state) and stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea.

Successfully ruled by a dynastic line of dukes, the Grand Duchy of

Lithuania (GDL) managed to penetrate the lands of Rus,

develop a highly advanced system of state administration and stave off

invading Crusaders longer than any other Central European power. Its statesmen conducted effective foreign

policy and military campaigns and created a multi-ethnic state. After the Grand Duchy’s incorporation into

a union with its neighbor, Poland,

its influence began to wane as Lithuanian nobility became more and more Polonised.

Officially Christianized as part of this union, and under increasing

Polish cultural pressures, the face of the Grand Duchy’s political relations

changed, and ultimately the GDL lost its unique position in the region. Though officially ended in 1795, the

history of the GDL continues to influence modern-day nationalist thinking in

the region. Both Belarus and Ukraine

point back to the days when they were part of the thriving GDL as proof of

their cultural and political distinction from Russia. And territorial disputes over the borders

of Lithuania and Poland were

the cause of great political tension well into the 20th

century.

Establishment of a State: Mindaugas and the

consolidation of Lithuanian lands

Although Lithuania’s

first king, Mindaugas, was crowned on July 6, 1253,

some historians argue that the establishment of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy

reaches back even farther. Though

there is little documentation for this time period, it is generally accepted

that for one to two hundred years prior to Mindaugas’

rule, Lithuanian tribes had already begun the process of unifying

themselves. During this time, most

people were free farmers who worked for so-called “good people,” landowners

who would eventually become nobles. Castles, manors and systems of defense

were established during this time.[1] Historian Tomas Baranauskas

argues that the GDL was founded around 1183.

By that time, the peoples of the region had established a high level

of military strength, a tribute system and a tax collection system organized

around manors. He concludes that Mindaugas did not establish the GDL but merely oriented

it toward the West.[2]

Wherever Mindaugas

actually entered in the process of the unification of the GDL, much progress

toward establishing the Grand Duchy was made under his rule. State institutions were formed, and,

militarily, Lithuania

resisted the attacks of the Teutonic Orders on one front and began to expand

its territory into the lands of Rus on the

other. Mindaugas

attempted to unite three worlds under his rule: pagan Lithuania,

Catholic Western Europe and Orthodox Russia.[3]

Unable to do so, he eventually claimed to convert to Christianity for

presumably political purposes. A very

strong regional leader, Mindaugas’ political

tactics involved intrigue and brutality among Lithuania’s princes and his own

family members. Ultimately, a

conspiracy was formed against him and he was assassinated in1263 along with

his two sons.

The Gediminian dynasty and the strengthening of the GDL

The 1300s brought new agricultural

technology, rapid social and economic development and some urban settlement.

Within Lithuania

proper, the old order of dukes was disappearing, a new class of nobles was

forming and specialized artisans were growing in number. In the area of foreign relations, the

joining of the lands of Rus to the GDL opened up

new trade routes.[4]

Grand Duke Gediminas came to power in 1316,

ushering in a new dynasty of leaders.

Gediminas employed several forms of

statesmanship to expand and strengthen the GDL. He invited members of religious orders to

come to the Grand Duchy, announced his loyalty to the Pope and to his

neighboring Catholic countries and made political allies with dukes in Rus as well as with the Poles through marriage to women

in his family. Gediminas’ political skills are

revealed in a series of letters written to Rome and nearby cities. In 1322, in a letter to Pope John XXII, he

claimed that his predecessors, including Mindaugas,

had been open to Christianity, but had been betrayed by the Teutonic

Knights. “Holy and honorable Father!,” he wrote, “We are fighting with the Christians not so

that we could destroy the Catholic faith, but in order to resist the harm

done to us…” He further mentions the

Franciscan and Dominican monks who had come to the GDL by invitation and were

given the rights to preach, baptize and perform other religious

services. The next year, he sent a

letter to neighboring cities announcing his acceptance of the Christian faith

and his intent not to harm, but to, “solidify eternal peace, brotherhood and

true love with all of Christ’s believers”.

He also included an open invitation to artisans and farmers to come

and live in the GDL, promising support and reduced taxes to those who would

come.[5] Gediminas’

“conversion” is mostly seen as a shrewd political move as he and most of his

subjects continued in the worship of pagan Lithuanian gods.

Along with his other political

accomplishments, Gediminas established Vilnius as the capital

of the GDL as early as 1323. During Mindaugas’ rule, he managed to establish a stable state

comprised of peoples of varied ethnicity and religious confessions. When his rule ended in 1341, he left the

GDL viable and strong.[6]

The Jagiellonian dynasty – the roles of Jogaila

and Vytautas

Jogaila succeeded to the throne in 1377

and presided over a time of continuing encroachment of Christianity as well

as territorial expansion. Caught

between Catholic Poland and the Teutonic Knights, Jogaila

chose union with the Poles, solidified in the 1385 Act of Kreva. For the hand of the Polish princess,

Jadwiga, Jogaila promised to convert to Roman

Catholicism. This signified the beginning of a partnership in which the

barons of the still autonomous principalities of Lithuania

and Poland

agreed to act by mutual consent.[7]

When Jogaila became King of Poland, the Gediminian dukes engaged in a power struggle over who

would rule Lithuania. In 1401, in the

Acts of Vilnius and Radom,

Jogaila’s cousin Vytautas

became the independent ruler of the GDL.

Yet, it was established that after his death his lands would be

returned to the kingdom

of Poland, and the tie

between the two nations was again reinforced.[8]

Despite Jogaila’s

conversion, and in light of his union with the Poles, the struggle with the

Teutonic Knights continued. After

several unsuccessful attempts by the Order and its allies to break the

military alliance of the GDL and Poland,

a combined Lithuanian-Polish army invaded the territory of the Order in July

of 1410 and fought what would be called the Battle of Žalgiris (Grunwald).[9] The combined forces of 39,000 swiftly

defeated the Order, killing almost half of its men, including the Grand

Master, and taking 14,000 prisoners for ransom.[10]

The victory was decisive, and the military power of the Order was effectively

destroyed.

Territorially, the two powers

continued their gradual expansion in the years after the defeat of the

Teutonic Knights, eventually stretching between the Baltic and the Black Seas by the 1420s. Socially, the Jagiellonian

period saw the rise of five estates: clergy, nobility, burghers, Jews and

peasants, with the nobles exercising power over the other four.[11]

The GDL in particular, under Vytautas, developed

trade, urban areas, a currency system and a coat-of-arms. Under his rule, a notion of statehood and

national consciousness developed which has been preserved throughout the

following centuries.[12]

The Grand Duchy

and Poland

under united rule

In the century following Vytautas’ reign, the population and diversity of the GDL

grew while the power of the Grand Duke began to decline. By the mid-16th century,

Lithuanians made up only around one-third of the total population of an

estimated 3 million people. Slavs,

Germans, Jews, Poles, Tatars and Karaites composed

the remaining two-thirds.[13]

Vytautas’ vision of a strong monarchical government

ruling alongside a centralized administrative state was realized only in

part. The Council of Lords developed

which grew in power and increasingly determined the actions of the Grand

Duke.[14]

Though the threat from the

Teutonic Knights had been neutralized in the previous century, in the 16th

century Lithuania faced

growing military pressure from Muscovy. At the same time, Poland began to experience growing danger from

Turkey

and the Crimean Tatars. For Lithuania, the prospect for a more permanent

union with Poland

primarily carried the advantage of a stronger defense. For Poles, such a union was mostly

motivated by a desire for the Duchy’s land.

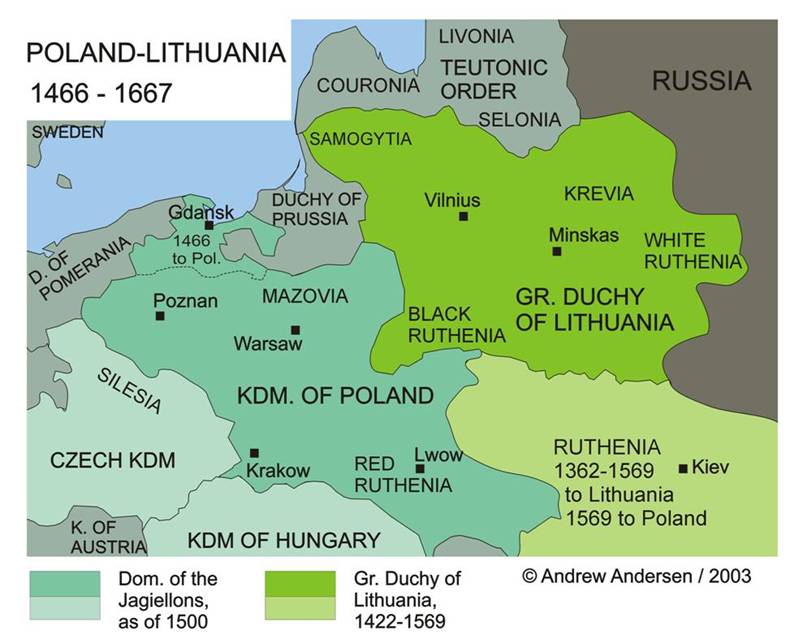

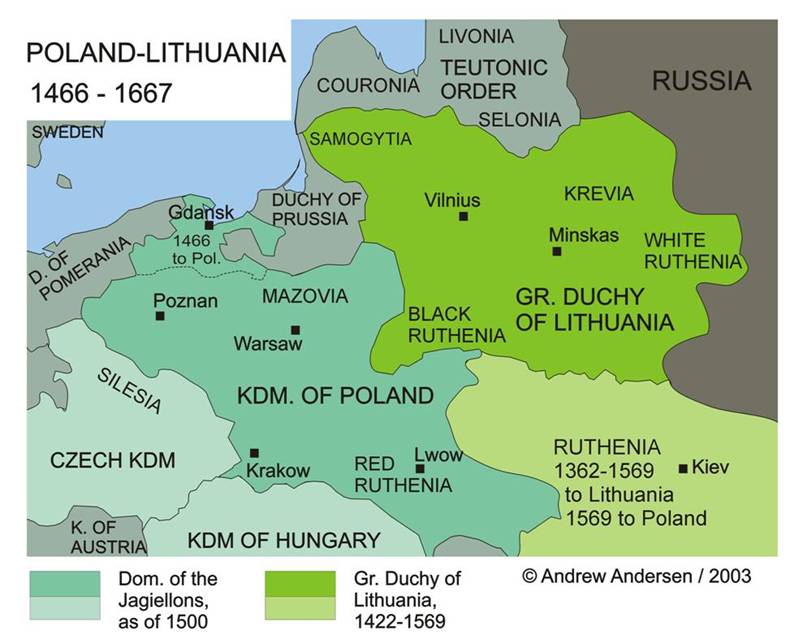

Zygimantas Augustas,

both the Grand Duke Lithuania and the king of Poland, had no heir, and his

death could have potentially severed Polish ties with the GDL. In 1569, in the Union of Lublin, the Kingdom of Poland and the GDL became a

commonwealth or Rzeczpospolita common

currency, governance and policy.

Nobles from both states had the right to own land and to sell goods

without paying taxes in either part of the commonwealth. The two states did retain their own

borders, names, armies and administrative powers.[15]

In 1572, concentration of power

into the hands of the nobles further increased with the implementation of an

election process that allowed nobles to withdraw their allegiance to the

monarch. This eventually led to a kind

of political paralysis as power gradually devolved to local governing

bodies. The diversity of peoples,

faiths and political convictions resistant to centralized administration made

the job of the leader of the commonwealth more and more difficult. Finally

the nobles rebelled against King Kazimierz, who was

forced to abdicate the throne.[16]

Beyond political changes, the

culture of the GDL changed rather significantly during this time as

well. By the end of 17th

century, the Polish language was spoken both by ordinary and high-ranking

nobles and officials of the GDL. In

1697, Polish became the official language of the commonwealth’s diet as well

as the GDL chancellery.[17]

Lithuanian language, as a result, became a language of the peasant class.[18]

Through the 1700s, Russian and

Prussian expansionism took its toll on the commonwealth. In 1772, the joint republic was partitioned

for the first time between Russia,

Prussia and Austria and

lost 30% of its land and 35% of its population.[19] In 1793, the Russians and Prussians

partitioned the Republic a second time, taking half of its remaining

territory. One year later, GDL and

Polish armies mounted separate insurrections against the occupying forces,

but it would end in defeat. In October,

1795, Russia, Prussia and Austria partitioned the remaining

lands of the Republic, thus marking the end of the commonwealth.[20]

Impact of

history on regional nationalism

Like most nations emerging from

rule by another power, many Lithuanians return to the past to define their

national identity. In this case,

though, there are competing claims upon history. In both the inter-war years and the

post-Soviet period, Belarus,

Ukraine and Poland have

made attempts to define their national rights and identities in relation to

the GDL. As early as the 1920s,

Belarusians were attempting to define the GDL as a Belarusian state. Along with Ukrainians, they sought ethnic

and historical separation from Russians and Poles.[21]

In 1991, as a show of protest against President Lukashenka’s plan to

reintegrate Belarus into Russia after independence, the leading opposition

party adopted the red and white flag with the Pahonya

coat of arms, symbols which originated during the reign of Vytautas. In the

absence of its own national ideology, Belarus was forced to create one

in order to prove its right to exist independently. Prime Minister Kebich remarked that, “with the poor national arsenal we

have received in all areas of spiritual life, we can hardly convince our

contemporaries and descendents that we have a history of our own.”[22]

In the case of Poland,

historical territory and identity became a source of conflict, not just an

ideological proposition. Because of

the history of free movement of Poles and Lithuanians in the commonwealth,

many ethnic Polish families established themselves in Lithuania and maintained strong ties with Poland. Beyond ethnolinguistic

and minority issues, some Poles believed that the city of Vilnius

(which it annexed and occupied) and other territory rightfully belonged to Poland. Some even advocated the re-establishment of

the Rzeczpospolita. A secret Polish military organization

operated in Lithuania

from 1918-1919 and conspired to overthrow the Lithuanian government.[23]

Diplomatic relations between Lithuania and Poland were effectively broken

until the end of the 1980s when the brewing independence movement brought the

former allies back together. Today,

the two countries are staunch supporters of each other’s post-communist

transition, including their respective NATO and European Union

aspirations.

Note: In reading about the GDL, you may

occasionally find the following Polish spellings of names:

Gediminas-Giedymin

Vytautas-Witold

Jogaila- Jagiello

Annotated bibliography of materials and suggested further readings

* denotes Lithuanian

language only sources

*Avižonis,

Konstantinis, ed., Rinktiniai Raštai, Rome: The Academy of Lithuanian

Catholic Studies, 1982

The Collected Works include documents

from the ruling regimes of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania regarding politics,

administration, religion, and relations with Sweden, Muscovy and Poland. The works include a few reviews of books in

English as well as some German-language documents regarding the

Lithuanian-Polish union.

Davies, Norman,

God’s Playground, vol. 1

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1982)

Chapter 5

of Davies’ book chronicles the role of Jogaila and

the Lithuanian Union with Poland (1386-1572).

Detailed descriptions of the Union of Kreva

(Krewo), defense against the Teutonic Knights,

Christianization and the legacy of the Jagiellionian

dynasty. Includes family tree diagrams

for the Jagiellons and Vasas

(p. 136).

Institute of Lithuanian

Scientific Society, “Lithuanian Classical Literature Anthology,” [sponsored

by UNESCO’s “Publica” series] copyright 1999-2002

<www.anthology.lms.lt/texts/1/turinys.html> (Accessed

April 24, 2002).

The texts of the letters of Grand Dukes Mindaugas

and Gediminas from 1254-1338. These letters include communications

between the Grand Duchy and Pope John XXII, the orders of Franciscan and

Dominican priests as well as the governments of major cities in the

region. The letters reflect political,

religious and economic relations of the Grand Duchy with Rome and its

neighbors and Gediminas’ efforts to build the

strength of the Duchy.

Joseph Lins, “Lithuania”, [from the Catholic Encyclopedia, vol.

IX, online copyright 1999] <www.newadvent.org/cathen/09292a.htm>

(Accessed April 24, 2002

Brief history of the Catholic Church in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania until

1659.

Kiaupa, Žigmantas, Jūrate

Kiaupienė and Albinas Kuncevičius, The History of Lithuania

before 1795, Vilnius:Lithuanian Institute of

History, 2000.

This book traces Lithuanian

history from the Mesolithic Period to the end of the Grand Duchy and the Lithuanian-Polish

commonwealth. Detailed treatment of

political with some social history.

Kirby, David, Northern

Europe in the Early Modern Period, The Baltic World 1492-1772, (London:Longman, 1990)

An excellent and

comprehensive source of political and social history of the region. Kirby does not focus very much on the GDL

or the Lithuanian-Polish commonwealth.

However, this source puts the role of the GDL into its greater

historical context.

*Makauskas, Bronius, Lietuvos Istorija, Kaunas:

Šviesa,

2000.

The History of Lithuania provides a general

introduction to the country’s history from the Baltic tribes to the

present.

Rowell, S.C., Lithuania Ascending. A

pagan empire within east-central Europe, 1295-1345, (Cambridge University

Press, 1994) 289.

In Chapter 8 Rowell recounts the conditions under which the GDL was

consolidated under Mindaugas and the Gediminian dynasty.

He pays particular attention to the presence of Christian movements

prior to the GDL’s official acceptance of Catholicism. The chapter includes an appendix of primary

sources in Russian and English related to the fall of Kiev to the

Lithuanians.

Sahm, Astrid,

“Political Culture and National Symbols: Their Impact in the Belarusian

Nation-Building Process” Nationalities Papers [Great Britian],

1999, 27 (4)

The article includes a good

description of post-1989 political efforts in Belarusia

to counter current pro-Russian politics with symbols of Belarusian distictiveness.

*Sliesoriūnas, Gintautas, Lietuvos Didžioji

Kunigaikštystė Vidaus Karo Išvakarėse: didikų

grupuočių kova 1690-1697 m Vilnius: Lithuanian

Institute of History, 2000.

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania

on the Eve of the Domestic War analyzes the causes and results of the war between

the nobles from 1690-1697. Within this

framework, the author also treats the oligarchy of the nobles as a whole

along with the development of the government of the Grand Duchy.

Tomas Baranauskas, “Medieval Lithuania,” <www.geocities.com/imantas2/etno/index-en.htm> (Last updated

January 26, 2002. Accessed

April 24, 2002).

Baranauskas, of the Lithuanian Institute of History,

includes a variety of articles on Lithuanian history from pre-history through

the Grand Duchy era (including maps and a currently incomplete chronology) as

well as articles related to Lithuanian society.

Valionis, Antanas, Evaldas Ignatavičius and Izolda Bričkovskienė, “From Solidarity to Partnership:

Lithuanian-Polish Relations 1988-1998,” Lithuanian Foreign Policy Review, 1998,

vol.2. Available at: <http://www.lfpr.lt/9802/phtml>

(accessed 06/03/02)

Description of

mutual support in the independence movement and subsequent development of

Lithuanian-Polish relations. Also

includes brief historical background.

*Varnienė, Janina, ed., Lietuvos istorijos

straipsnių ir dokumentų rinkinys. Vilnius: Arlila, 1999.

The collection of documents

and articles from Lithuanian history includes a very wide range

of materials from Lithuanian pre-history to the time of publishing. Topics

include: pre-state history, the era of the Gediminas

dynasty and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Polish-Lithuanian republic,

Lithuanian relations with Sweden and the Russian Empire, both World Wars and

the inter-war period, Soviet Lithuania and the recreation of the independent

Lithuanian state.

Zejmis, Jakub, “Belarusian National Historiography and the Grand Duchy of

Lithuania as a Belarusian State,” Zeitschrift fur Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung , 1999, 48, p.

383-396.

Describes the extent to which some Belarusian historiographers contend

that the GDL was a product of Belarusian influence.

*Žirgulys, A., ed. Lietuvos

Metraštis: Bychovco kronika. Vilnius: Vaizdas Printing, 1971.

The Lithuanian Chronicles (or The

Chronicles of Bychovcas) is a collection of historical,

political and literary documents from the age of the Grand Duchy.

Originally

published at http://depts.washington.edu/baltic/papers/

|

|