|

|

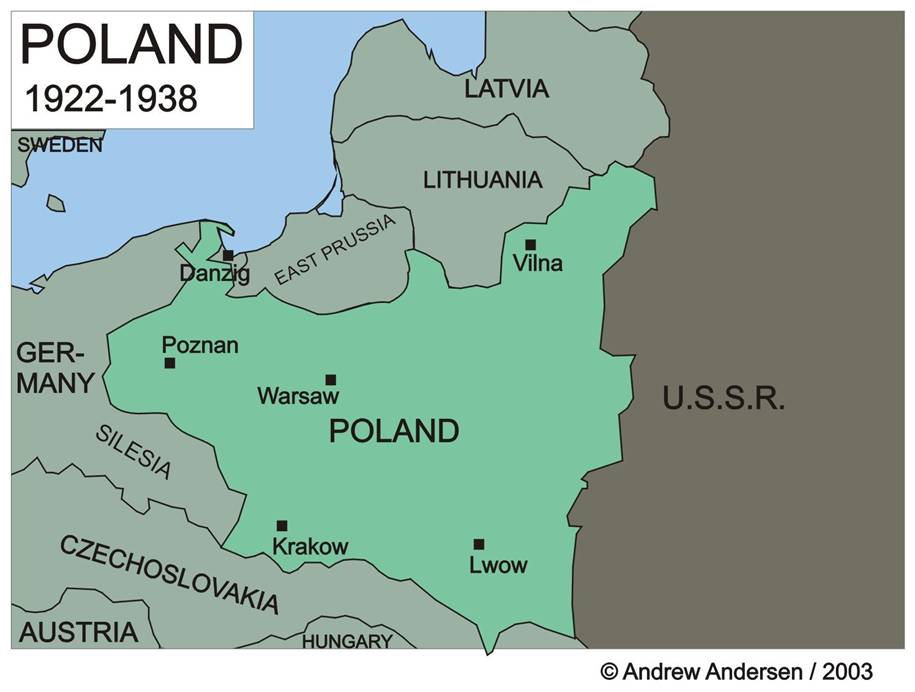

Poland: Revolution and Rebirth

By Mieczyslaw Kasprzyk

Maps: Andrew Andersen

|

Napoleonic Poland;

The Duchy of Warsaw

The Poles felt that one way of restoring independence

was to fight for Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1791 Dabrowski

organised two legions to fight the Austrians in

Lombardy and, later, for the French in the Iberian

Peninsula.

Kniaziewicz organised the Polish Danube

Legion to fight against the Germans in 1799.

Napoleon

used the Polish Legions in all his campaigns; against Russia, Austria

and Prussia, in Egypt, in the West Indies (Santo

Domingo), and in Spain

(where they fought the British and inspired the formation of the English

lancers equipped with Polish-style uniforms and weapons). Some of the Poles

became very disillusioned with Bonaparte, realising

that they were being manipulated.

Later, in

1806, the French armies defeated the Prussians at Jena

and entered Posen (Poznan)

led by the Poles under Dabrowski. A year later

Napoleon and the Tzar, Alexander, met at Tilsit and agreed to set up a Polish State made up of the

lands the Prussians had taken in the second partition. This was the Duchy of

Warsaw. Napoleon used the Duchy as a pawn in his political game and in 1812

called upon the Lithuanians to rebel as an excuse to attack Russia. The

Poles, flocking to his standard in the hope of resurrecting the Commonwealth,

formed the largest non-French contingent, 98,000 men. Polish Lancers were the

first to cross the Niemen into Russia, the first to enter Moscow, played a

crucial part in the battle of Borodino and, under Poniatowski,

covered the disastrous French retreat, being the last out of Russia; 72,000

never returned.

Despite

the cynical way that Napoleon treated the Poles they remained loyal to him and,

when he went into exile on Elba the only

guards that Napoleon was allowed were Polish Lancers.

The "Congress Kingdom"

In 1815 at the Congress of Vienna the Duchy was

partitioned and a large part went to Russia. In Austria and Prussia

there was repression of all Polish attempts to maintain the national culture,

but in Russia, fortunately,

the Tzar, Alexander I, was a liberal ruler who agreed

to the setting up of a semi-autonomous "Congress Kingdom"

with its own parliament and constitution. This became a time of peace and

economic recovery. In 1817 the University

of Warsaw was founded.

But the accession of Tzar Nicholas I to the throne in

1825 saw the establishment of a more repressive regime.

In 1830,

after the revolution in France

and unrest in Holland,

Nicholas decided to intervene and suppress the move towards democracy in the

West. He intended to use the Polish Army as an advanced force but instead

propelled the Polish patriots into action. On the night of November 29th the

cadets of the Warsaw

Military College

launched an insurrection. The Poles fought bravely against heavy odds in former

Polish territories around Wilno, Volhynia

and the borders of Austria

and Prussia.

The insurrection spread to Lithuania

where it was led by a woman, Emilia Plater. For a

while victory actually lay in their grasp but indecision on the part of the

Polish leaders led to defeat. Warsaw was taken

in September 1831, followed by terrible persecution; over 25,000 prisoners were

sent to Siberia with their families and the Constitution of the "Congress Kingdom" was suspended.

The 1830

Revolution inspired the work of two great Poles living in exile; Chopin, the

composer, and Mickiewicz, the poet.

The "Great Emigration"

The failure of the Insurrection forced thousands of

Poles to flee to the West; Paris

became the spiritual capital. Many of these exiles contributed greatly to

Polish and European culture. Joachim Lelewel became Poland's

greatest historian, Chopin her greatest composer, and Mickiewicz, Slowacki, Krasinski and Norwid among her greatest poets. Adam Czartoryski

set up court at the Hotel Lambert, in Paris,

which played an important part in keeping the Polish question alive in European

politics.

"For Your Freedom and Ours"

The insurrection in the semi-independent City of Krakow in 1846 was doomed

from the start. The insurrectionists had hoped to gain the support of the local

peasantry (recalling the victory at Raclawice) but

the peasants, having never benefited from the liberal ideals proposed by the intelligensia, used the insurrection as an excuse to rid

themselves of their landlords; it was the last "jacquerie"

(or peasants' uprising) in European history. The insurrectionist forces were

defeated by a combination of Austrian and peasant forces at the battle of Gdow and the insurrection was put down with great brutality

by the Austrians, resulting in the abolition of the Commonwealth of Krakow.

In 1848

"the Springtime of Nations" (a revolutionary movement towards greater

democracy in much of Europe) saw large-scale contributions by the Poles; in

Italy, Mickiewicz organised a small legion to fight

for Italian independence from Austria, whilst in Hungary, Generals Dembinski and Bem led 3,000 Poles

in the Hungarian Revolution against Austria. There were also unsuccessful

uprisings in Poznan (Posen), against the

Prussians, and in Eastern Galicia, against the

Austrians.

Starting

in 1863, the "January Uprising" against the Russians lasted for more

than a year and a half. A Provisional government was established and more than

1,200 skirmishes were fought, mostly in the deep forests under the command of Romuald Traugutt. Italian help

came from the "Garibaldi Legion" led by Colonel Francesco Nullo. In 1864 Traugutt and four

other members of the Provisional government were captured in Warsaw and publicly executed.

The

Uprising was finally put down in 1865, and the Kingdom of Poland

was abolished and a severe policy of persecution and "Russification"

established. The University

of Warsaw and all schools

were closed down, use of the Polish language was forbidden in most public

places and the Catholic Church was persecuted. The Kingdom

of Poland became known as the "Vistula Province".

In the

Prussian occupied zone the aim was to totally destroy the Polish language and culture;

from 1872 German became compulsory in all schools and it was a crime to be

caught speaking in Polish. There was a systematic attempt to uproot Polish

Peasants from their land. A special permit was needed to rebuild any farm

buildings damaged or destroyed by fire or flood, but none were ever granted to

Poles. One peasant, Wojciech Drzumala,

challenged this law by living in a converted wagon.

In

Austrian Poland, Galicia,

conditions were different. After 1868 the Poles had a degree of

self-government, the Polish language was kept as the official language and the

Universities of Krakow and Lwow were allowed to

function. As a result this area witnessed a splendid revival of Polish culture,

including the works of the painter Jan Matejko, and

the writers Kraszewski, Prus

and Sienkiewicz.

All three

powers kept Poland

economically weak in this period of technological progress. Despite this the

Poles managed to make some progress; the textile industry began to flourish in Lodz (the "Polish

Manchester") and coal-mining developed rapidly. In Prussian Poland,

despite ruthless oppression, the Poles concentrated on light industry and

agriculture (and before long Poznan became the

chief source of food for the whole of Germany). In Silesia, under German rule since 1742, the

development of mining and heavy industry made her a chief industrial centre and

thus the Prussian attempt to exterminate all traces of Polish language and

culture was at its most ruthless, yet they survived.

Despite

its abolition by Kosciuszko in 1794 the partitioning powers restored serfdom.

It was not abolished in Prussia

until 1823, in Austria until

1848 and in Russia

until 1861 (but not in her "Polish" territories).

In 1905

the Russo-Japanese War saw a series of humiliating defeats for the Russians and

civil unrest in Russia.

In Poland

there was a wave of strikes and demonstrations demanding civil rights. Polish

pupils went on strike, walking out of Russian schools and a private organisation, the "Polska Macierz Szkolna"

("Polish Education Society"), was set up under the patronage of the

great novelist, Henryk Sienkiewicz.

Then, in

1906, Jozef Pilsudski, a founder-member of the Polish

Socialist Party (PPS), began to set up a number of paramilitary organisations which attacked Tzarist

officials and carried out raids on post offices, tax-offices and mail-trains.

In Galicia the Austrian

authorities turned a blind eye to the setting up of a number of

"sporting" clubs, followed by a Riflemen's Union.

In 1912, Pilsudski reorganised these on military

lines and by 1914 had nearly 12,000 men under arms.

PART II See also: “The Rebirth of Poland” by Anna M. Cienciala

The First World War: 1914-1918

On the outbreak of war the Poles found themselves

conscripted into the armies of Germany,

Austria and Russia,

and forced to fight each other in a war that was not theirs. Although many

Poles sympathised with France

and Britain

they found it hard to fight with them on the Russian side. They also had little

sympathy with the Germans. Pilsudski considered Russia

as the greater enemy and formed Polish Legions to fight for Austria but

independently. Other Galician Poles went to fight against the Italians when

they entered the war in 1915, thus preventing any clash of conscience.

Almost

all the fighting on the Eastern Front took place on Polish soil.

On the

collapse of the Tzarist regime in Russia in 1917, the main purpose for fighting

alongside the Central Powers, Germany

and Austria, disappeared. They had made many promises of setting up an

independent Poland

but had proved to be very slow in carrying these promises out. When Pilsudski's

Legions were required to swear allegiance to Germany they refused and Pilsudski

was imprisoned. In 1918 when, at Brest Litovsk, the

Central Powers signed a peace treaty with Russia, which was detrimental to

Poland, the Second Brigade under General Haller revolted and marched into the

Ukraine where they joined other Polish forces already formed there and fought

against the Germans, eventually being surrounded and defeated.

At the

outbreak of the revolution in Russia Polish army units had joined together to

form the First Polish Corps under General Jozef Dowbor Munsnicki and tried to

reach Poland

but were disarmed by the Germans. Escapees and volunteers reorganised

themselves into a new army at Murmansk in the

Arctic and fought alongside the British on the shores of the Whits Sea

and beside the French at Odessa, as well as in

the Far East at Siberia. Later they managed to

reach Poland.

Roman Dmowski, founder of the right-wing Nationalist League, had

foreseen that Germany was

the real enemy and gone to France

where the "Bayonne Legion" was already fighting alongside the French

Army. He and Paderewski formed a Polish Army which consisted of volunteers from

the United States, Canada and Brazil together with Poles who had

been conscripted into the German and Austrian armies and had become POWs. This

Army became known as "Haller's Army" after its commander who had

escaped from Russia to France.

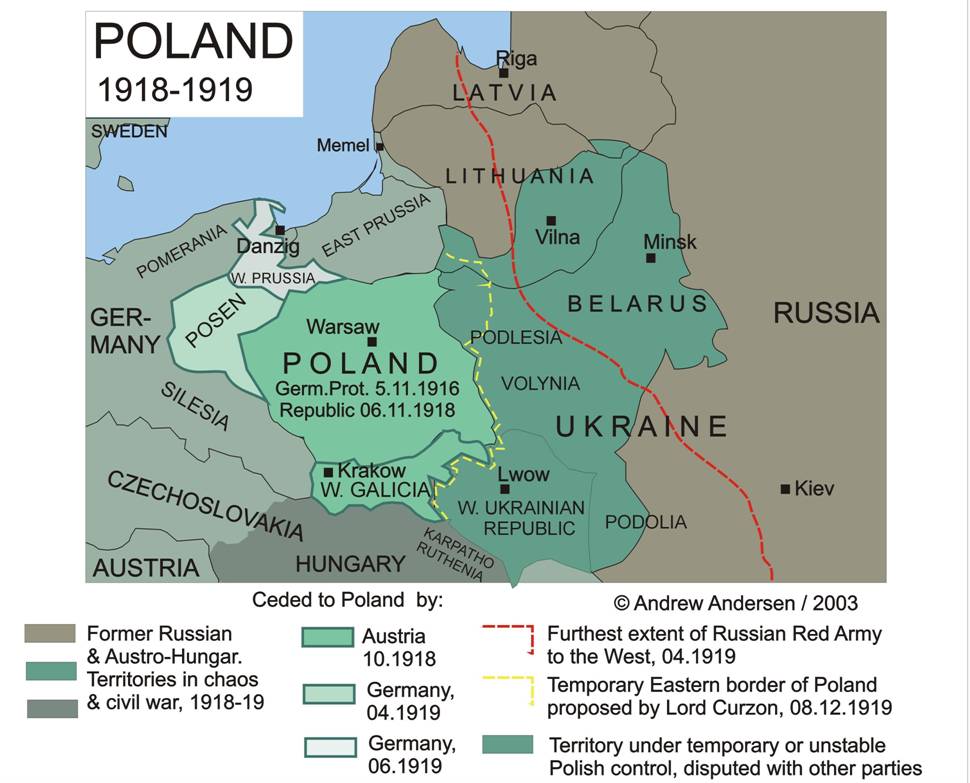

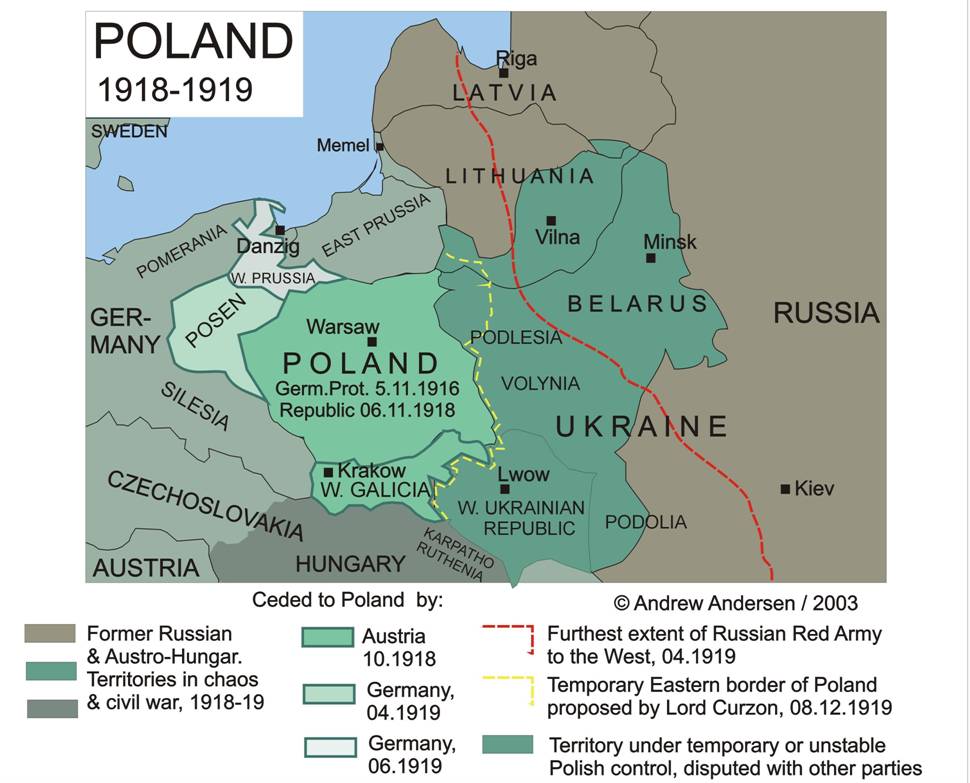

Rebirth: 1918-1922

All sides, from Tzar

Nicholas of Russia to President Wilson (in his Fourteen Points) had promised

the restoration of Poland yet in the end the Poles regained independence

through their own actions when, first Russia, and then the Central Powers

collapsed as a result of the War.

In 1918,

on the 11th November, Pilsudski, having been released by the Germans,

proclaimed Polish Independence

and Became Head of State and Commander-in-Chief, with Paderewski as Prime

Minister. An uprising liberated Poznan and,

shortly after, Pomerania (which gave access to

the Baltic).

In the

chaos that followed the collapse of the Powers new states had arisen; Lithuania, Czechoslovakia

and the Ukrainian

Republic. All these

states laid claims on territory occupied by Poles.

The Poles

liberated Wilno from the Lithuanians in 1919,

reoccupied the area around Cieszyn (which had been

invaded by the Czechs) and annexed the Western Ukraine when the Ukrainian Republic,

which had been supported by Poland,

collapsed under attack from Soviet forces.

The Red

Army, having crushed all counter-revolutionary forces inside Russia, now turned its attention on Poland.

By August 1920 they were at the gates of Warsaw.

On August 15th the Polish Army under Pilsudski, Haller and Sikorski

fought the Battle of Warsaw (the "Miracle on the Vistula"), routed

the Red Army and saved a weakened Europe from

Soviet conquest. An Armistice was signed at Riga

in October, followed by a Peace Treaty in March 1921 which determined and

secured Poland's

eastern frontiers.

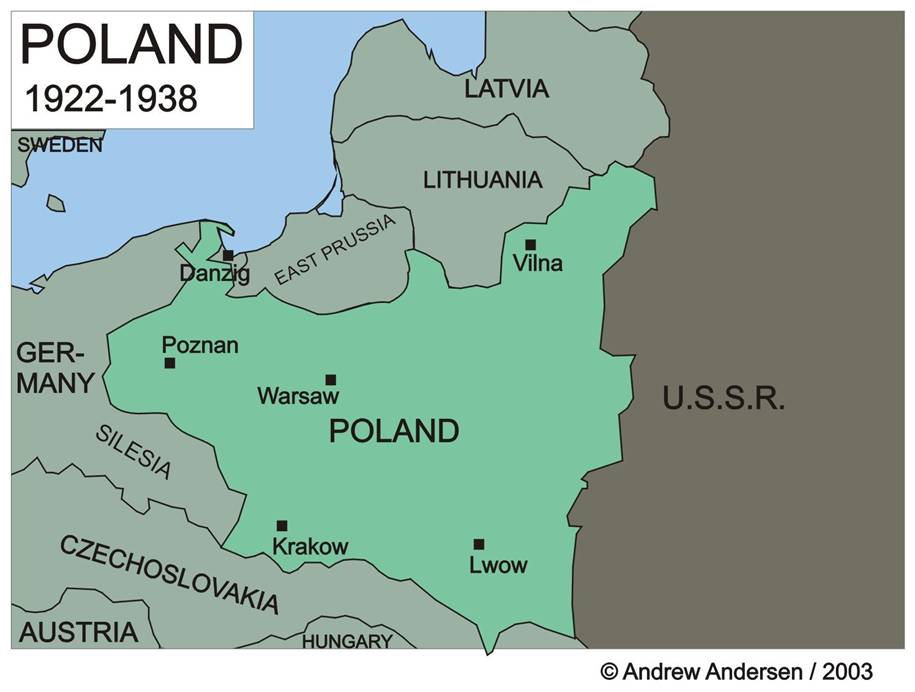

In 1922

part of Upper Silesia was awarded to Poland

by a Geneva Convention following three uprisings by the Polish population who

had been handed over to Germany

at the Peace Treaty of Versailles.

The Second

Republic: 1921-1939

On March 17th, 1921, a modern, democratic constitution

was voted in. The task that lay ahead was difficult; the country was ruined

economically and, after a hundred and twenty years of foreign rule, there was

no tradition of civil service.

Marshal

Pilsudski resigned from office in 1922, and the newly-elected President,

Gabriel Narutowicz, took office only to be

assassinated a week later.

Seeing

that the government lacked power because of party strife, Pilsudski took

control by a coup d'etat in 1926 and established the Sanacja regime intended to clean-up ("sanitise") political life. By 1930 this had become a

virtual dictatorship.

Despite

all her problems Poland

was able to rebuild her economy; by 1939 she was the

8th largest steel producer in the world and had developed her mining, textiles

and chemical industries. Poland had been awarded limited access to the sea by

the Peace of Versailles (the "Polish Corridor") but her chief port,

Gdansk (Danzig) was made a free city (put under Polish protection) and so, in

1924, a new port, Gdynia, was built which, by 1938, became the busiest port in

the Baltic.

There

were continual disputes with the Germans because access to the sea had split Germany into two and because they wanted Danzig under their control. There problems increased when

Adolf Hitler took power in Germany.

In 1939,

under constant threat from Germany,

Poland entered into a full

military alliance with Britain

and France

In August,

Germany and Russia signed a secret agreement concerning the

future of Poland.

Originally published at http://www.kasprzyk.demon.co.uk/www/HistoryPolska.html

BACK TO POLISH HISTORY

SEE ALSO RELATED BIOGRAPHIES