|

Poland: The Struggle for Independence 1795-1864

By Anna M. Cienciala (Maps.: Andrew

Andersen)

VIDEO

|

Overview.

The year 1864 marks a

great turning point in modern Polish history. The failure of the second great

revolt against Russia

within three decades ended what is known as the "Romantic" period of

insurrections, and led to rethinking political

strategies to regain independence. However, we should note that beginning

around 1892, a new revolutionary- insurrectionary trend appeared with the

founding of the Polish Socialist Party Abroad followed in 1893 by the

establishment of the Polish Socialist Party (Polish acronym PPS) in

Warsaw. One of its founders was Jozef

Pilsudski (1867-1935, pron. Peelsootskee),

who headed the party in Lithuania. The same period saw the founding of the conservative, Catholic, National

Democratic Movement led by Roman Dmowski

(1864-1939, pron. Demofskee). Both movements

began with the goal of regaining Polish independence but in 1906-16 the

National Democrats, who saw Poland's

greatest enemy in Germany,

followed a policy of cooperation with Russia,

while Pilsudski, who saw Russia

as the greatest enemy, lined up with the Central Powers against in her 1914-17.

Key Characteristics of the period

1795-1864.

A. The Struggle for Independence

- but note that between insurrections there were also attempts by the Polish

social elite to find a "modus vivendi,"

that is to get along with the foreign rulers of Poland.

B. Modern Polish national

consciousness began to develop in the period of revival and reform, 1772-91.

It inspired the authors of the 3 May 1791 Constitution and was manifested by

armed struggle in the Kosciuszko

Uprising of 1794, when peasant volunteers armed with scythes mounted

on long pikes fought Russian troops. National consciousness developed further

in the period of the Napoleonic Wars (1797-1815), then in the short lived Kingdom of Poland

(1815-30), and was greatly strengthened by the two great revolts against Russia of

1830-31 and 1863-64.

C. Until 1830, that is, in the period of the Duchy of Warsaw (1807-12)

and the Kingdom of Poland (Congress Poland, 1815-30), the social and

political elite was made up of nobles, seconded by army officers of gentry

(minor noble) origin. After the failure of the first revolt against Russia, 1830-31, political leadership passed to poets

and writers of the "Great Emigration," most of whom settled in France.

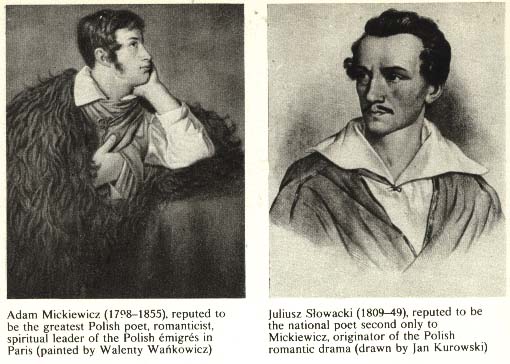

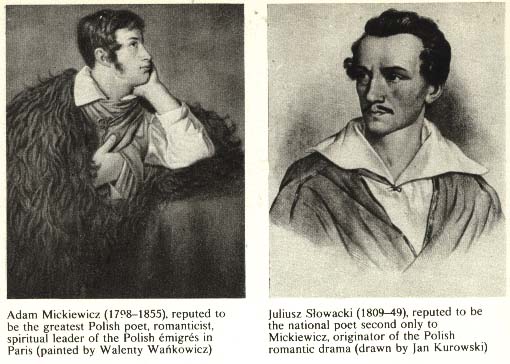

D. Poets and musicians played an especially important part in

developing national consciousness in the period 1831-63. The poet Adam

Mickiewicz (1798-1855, pron. Meestkyeveetch)

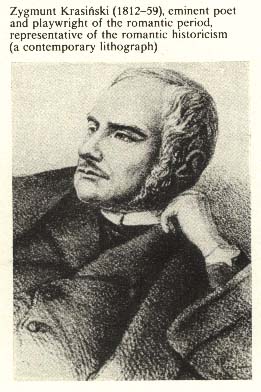

was the most important in this respect, though Zygmunt

Krasinski (1812-1858) and Juliusz

Slowacki (1809-1849) also contributed

greatly to this development. The composer and piano virtuoso Frederic Chopin(1810-1849,

pron. Shohpehn) expressed Polish yearning for

independence in his music.

E. The evolution of Democratic Ideas can be seen in the Polish

Democratic Society, which was established by Polish emigre

officers in France,

and especially in its program, published in 1839. The key ideas were the emancipation

of the Polish peasants - with compensation for the landlords - which

was combined with the belief that Poland would rise again as the result

of a coming "War of the Peoples" against the monarchies of

Europe, which would overthrow the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian monarchies

that ruled Polish lands.

1. The Poles in

the Napoleonic Wars.

Polish nobles and

gentry were divided into two groups: (a) those with a Russian orientation, who

worked for the union of all Polish lands in an autonomous Kingdom within the

Russian Empire, with the Tsar as King of Poland, and (b) those who followed the French orientation, and put their hopes for

an independent Poland

in Napoleon.

The most prominent leader of the Russian orientation was Prince

Adam Jerzy Czartoryski

(1770-1861, pron. Chartohryskee), a friend and

adviser of TsarAlexander I until 1815.

He fell in love with Alexander's wife, and their love affair had Alexander's

permission because his was an arranged, loveless marriage. However, after his

death, she was not allowed to marry him and he married late in life, when he

was in exile in Paris.

Czartoryski's political career reflected the

vicissitudes of Poland's

fate throughout his long life.

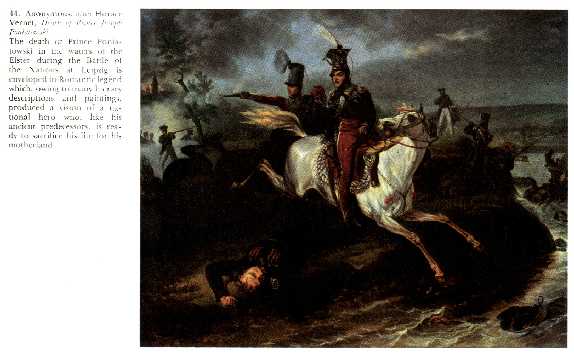

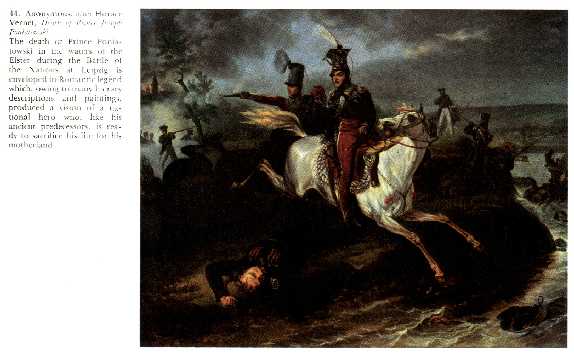

The most prominent

leaders of the French orientation were General Jan Henryk

Dabrowski (1755-1818, pron. Dohmbrofskee), and Prince Jozef

Antoni Poniatowski

(1763-1813, pron. Pohnyatofskee), nephew of King Stanislas Augustus Poniatowski. Dabrowski created the Polish Legions in Italy, 1797,

and they fought for Napoleon. His name figures in the Polish marching song

written at this time by Jozef Wybicki (1747-1822, pron. Vyhbeetskee),

and sung to the tune of a Polish mazurka, a folk dance of Mazovia.

(In the interwar period, 1919-39, it became the Polish

national anthem). Poniatowski was War Minister

and a general in the army of the Duchy of Warsaw, also a Marshal of France.

Prince Jozef Poniatowski at the Elster River,where he died.

[from Topolski, Outline

History of Poland].

The French

orientation seemed to be winning until the defeat of Napoleon in Russia, 1812.

Meanwhile, the Duchy of Warsaw, created in 1807 and expanded to include

Austrian Poland in 1809, received the Napoleonic Code and was ruled by

the Frederick Augustus, the Elector of Saxony,

under French supervision. The Duchy of Warsaw was, in fact, treated pretty much

as a French colony - though a willing one - and was exploited economically by France.

THE YEAR 1812.

About a quarter of

Napoleon's "Grande Armee" of

some 600,000, which invaded Russia

in June 1812, was made up of Poles. A poetic image of this army's march through

Lithuania,

as seen by Polish nobles, is pictured in Adam Mickiewicz's great epic poem Pan

Tadeusz (Mr.Thaddeus).

Or the Last Foray into Lithuania, which illustrates Polish gentry life in Lithuania at

this time. (The Poles were the landowning class in most of the country).

Written by Mickiewicz and published in Parisian exile in the early 1830s, this

is a perennial favorite with Polish readers and has been translated into many

languages. (The best English translation is by Kenneth

Mackenzie, published by the Polish Cultural Foundation, London, 1964, with

later reprints).

The tale of Poles

fighting in Napoleon's army in Spain

and then retreating with the "Grande Armee"

from Russia

is told in Stefan Zeromski's novel Popioly (Ashes), which was made into a

wonderful film by Polish film director, Andrzej Wajda.

2. The

decisions of the Congress of Vienna,

1814-15, concerning Polish lands.

After Napoleon's

final defeat by British and Prussian armies at Waterloo,

Belgium, on June 18, 1815,

the victorious allies proceeded to implement the peace settlements they had

worked out at the Congress of Vienna,

Sept. 1814- June 8, 1815.

Tsar Alexander I of Russia

wanted to unite all Polish lands under the Russian crown - which was also the

goal of his adviser, Prince Adam Czartoryski.

However, Prussia and Austria refused

to give up their Polish acquisitions for compensation elsewhere. They were

supported in this by Gt.Britain and the newly

restored French monarchy - both of whom feared a too powerful Russia in Europe.

However, Austria and Prussia did agree to give up their shares from

the Third Partition to a Kingdom

of Poland united with Russia but

without its former eastern lands, which greatly disappointed Czartoryski and all those who had supported Russis against Napoleon. All three powers guaranteed the

rights of their Polish subjects to cultural development and economic unity.

Finally, Austria

agreed to set up The Republic of Cracow, which became a symbol of

Polish independence.

3. The Kingdom

of Poland (Congress Poland),

1815-1830/31.

Tsar Alexander I granted his new Kingdom a liberal constitution, which included a two

chamber legislature (Seym and Senate). The kingdom

also had its own administration and army. Alexander viewed the liberal

constitution as an experiment; if it worked, it might be extended to Russia.

Unfortunately for the Poles he appointed his brother, the Grand Duke

Constantine, as commander in chief of the Polish Army and the large Russian

force stationed in the Kingdom. He was married to a Polish lady, who sometimes

succeeded in tempering his brutal character. The pardoned, former Napoleonic

General Jozef Zajaczek was

appointed Viceroy, but without real power , which was

in the hands of Nikolai Novosiltsev, whom

Alexander II appointed to oversee Polish affairs.

There was some

important economic development at this time, especially in the textile

industry which had its center in Lodz

(pron: Woots). There

was also some significant educational development in the Kingdom. Furthermore,

Prince Adam Czartoryski, who was

curator of the educational region of Vilna

(P. Wilno, Lith. Vilnius) extended the Polish

educational reforms of the 1772-93 period to former eastern Poland, now Russia, where the noble class was

Polish. He was replaced by Novosiltsev in 1823, who

introduced a repressive policy, in line with Tsar Alexander's change of mind.

Alexander turned

conservative after the 1820-21 revolts in Europe, when he lent his moral and

diplomatic support to Austria.

In the Kingdom of

Poland, the imposition of

censorship led to the development of secret

societies among students and army officers. The students were attracted to

western liberal ideas, and Adam Mickiewicz became famous for his

"Ode to Youth," which was really an ode to freedom. Mickiewicz, a

member of the Philotmat society at the University of Wilno, was exiled to Russia, where

he made the acquaintance of Pushkin and other Russian literary figures. (He left for Western Europe in 1830). The officers resented

the brutal methods of their commander-in-chief and Viceroy of Poland, the Grand

Duke Constantine. They also resented their dim perspectives of

advancement in the army.

Alexander I died on December 1, 1825, at Taganrog,

on the Sea of Azov. There is some mystery

about his death, allegedly of the plague. His body was not buried with the

other Tsars and their families in St.Petersburg, and

rumors persisted that he had not died but became a hermit. Whatever the case

may be, he was succeeded by his brother Nicholas, who became Nicholas I (1796-1855,

ruled 1825-55). He put down a revolt against his coronation, led by

liberal-minded Russian nobles and known as the Decembrist Revolt. He

meted out ruthless punishment to the rebels.

Some Polish nobles

sympathized with the Decembrists and the Polish Senate refused to condemn as

traitors the nobles who had contacts with the Decembrists. Nicholas I,

who had expected condemnation, was furious.

3. Factors leading to the Polish Revolt against Russia,

1830-31.

a. Revolutions broke out all over Europe in 1830, beginning with the July

revolution in Paris

against King Charles X Bourbon, who was succeeded by King Louis

Philippe of the House of Orleans, known for his liberal views. In August,

the Belgians revolted against Dutch rule, and Belgian independence was won with

British diplomatic support. Revolts broke out in some of the German states,

toppling rulers. In Feb.1831, there were revolts in Modena

and Parma, with the goal of uniting Italy. There

were also revolts in the Papal States.

However, all were put down.

b. In Warsaw,

the cadet officers' conspiracy against the Grand Duke Constantine

was in danger of being discovered; by November, the secret police were on their

trail.

c. In November 1830, Tsar Nicholas I declared

he would march to help the Dutch King William against the Belgians, and

would include the Polish army in this expedition. This was the last straw for

the Polish cadets.

4. Revolt and Failure.

On Nov. 29, 1830, the cadets revolted in Warsaw and tried

to kill Constantine,

but he escaped. They people of Warsaw

rose up in support of the cadets. A new government was formed, with Prince

Adam J. Czartoryski at its head. He only

accepted leadership in hope of reaching a negotiated peace with Nicholas

I, but the Tsar demanded surrender so he was dethroned as King of Poland.

Though the Polish

army scored some victories, the Poles could not win because: (a). They were outnumbered 10-1 by the Russians, and (b). They

received no foreign support - as did the Greeks in their War of Independence

against the Turks. (c) Austria

and Prussia

gave support to the Russians.

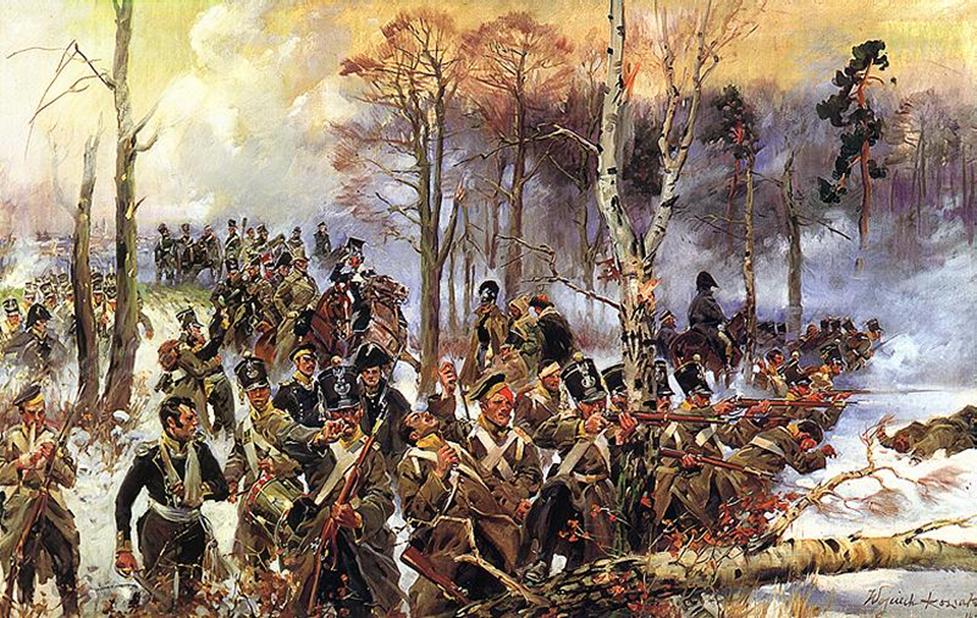

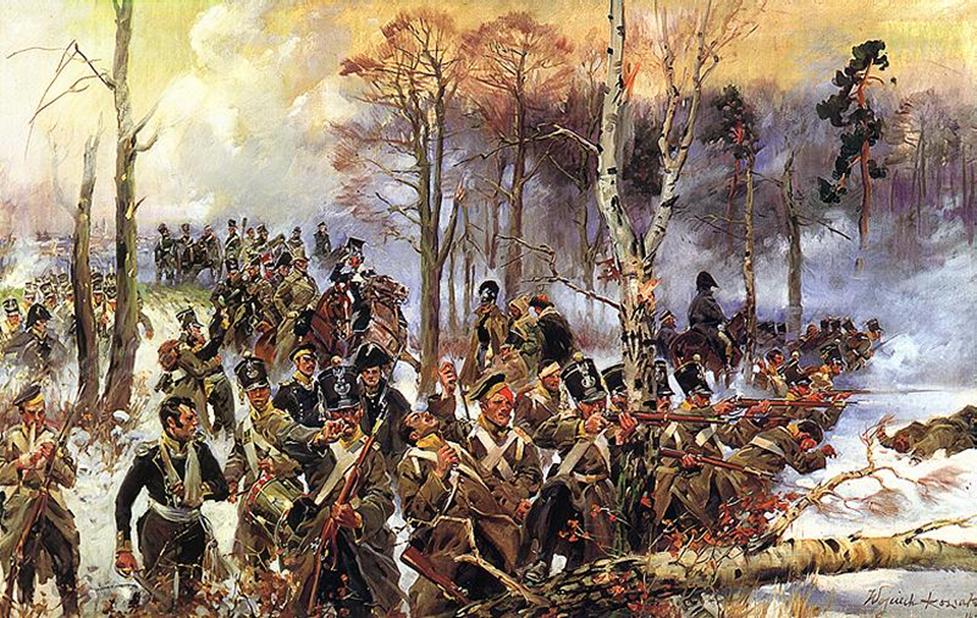

One of the key battles of the 1830-31 revolution against Russia.

[from Topolski, History of

Poland].

Even so, the fighting lasted for over a year. Russian

retribution was ruthless. Many insurrectionists were sentenced to hard

labor or service in the ranks of the Russian army. Hundreds of

Polish gentry families were deported to Siberia from former

eastern Poland,

being replaced by Russian landowners. The former Kingdom of Poland

was placed under military rule, headed by General Ivan F.Paskevich (1782-1856) who had defeated the Poles

and was made "Prince of Warsaw." At the same time, the Austrian and

Prussian governments repressed their Polish subjects too.

5. Importance of the 1830-31 Revolution.

(a) It increased Polish national consciousness because

Poles from Austrian and Prussian Poland had joined the revolt against Russia.

(b) Many in the

Polish elite saw the defeat as due more to mistakes in

military and political leadership than to Russian might. They came to

believe that if the Polish leaders had offered emancipation to the peasants,

this would have provided a mass army to defeat the Russians. Thus, Emancipation

came to be the program of a large group of Polish emigres.

(They overlooked the fact that emancipation in 1830-31 would

have ruined the gentry, who were the backbone of the revolution, and that even

a large Polish army could not have won without foreign support against the

vastly superior Russians, who also had the backing of Austria and Prussia).

6. The Great Emigration; the revolts of 1846 and

1848; the Crimean War, 1854-45.

An estimated 10,000 Poles, mostly nobles and gentry, preferred exile

Siberia or living under Russian rule in Poland. Most settled in France

and divided into two main political groups:

(a) Conservatives

led by Prince Adam J. Czartoryski, who

resided in the Hotel Lambert, Isle

St.Louis,

Paris (now the Bibliotheque Polonaise and museum). He

worked to secure French and British support to regain Polish independence,

hoping they would get involved in a war with Russia,

defeat the latter, and thus bring about an independent Poland. Czartoryski and his group also advocated conservative

agrarian reform, that is, commuting peasant labor dues

for money rents.

(b) The Polish

Democratic Society (PDS), mainly former officers, advocated the

abolition of serfdom, though with compensation for the landlords. They called

for the overthrow of monarchies in a "War of the Peoples," which

would bring Polish indepedence. One of the PDS

leaders was the historian Joachim Lelewel (1786-1861).

The PDS published their program in 1839; it is known as "The Poitiers Manifesto,"

because it was published in the city to which most former Polish officers were

relegated by the French government. (see Biskupski & Pula, Polish Democratic Thought, pp.

199-209).

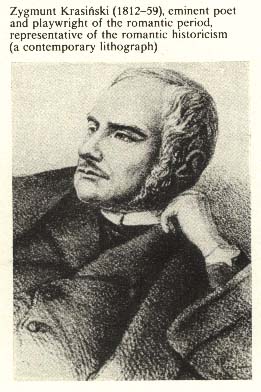

The great emigration

produced a great age of Polish literature. There were three great

Polish poets, who were also playwrights: Adam Mickiewicz (1798-1855); Zygmunt Krasinski

(1812-1859, pron. Krahseenskee) and Juliusz Slowacki

(1809-1849, pron. Swohvatskee). Mickiewicz's great

patriotic work was the play "Forefathers' Eve;" another was: "Konrad Wallenrod." But he is

best known for his epic poem: Pan Tadeusz,

(All these works are available in English). Poles love the other two poets as

well, but Mickiewicz became the national poet of Poland. His romantic view of Poland and the

struggle for Polish independence, deeply influenced several generations of

Poles, and with the spread of reading among workers and peasants the late 19th

century, it reached them as well. This was so even though his works were banned

in Russian and Prussian Poland, and allowed in Austrian Poland only after 1868.

(See: Charles Jelavich, The Habsburg Monarchy,

Polish Nationalism: Mickiewicz, pp.1-13)

The music of Frederic

Chopin (1810-1849) has also inspired generations of Poles and still does so

today. His father was French; came from Lorraine

to Poland

as a music teacher and married a Polish lady. Frederic was a child prodigy as a

pianist; he also collected folk tunes which he later used as themes in his

compositions, especially the Mazurkas. He lived in France from 1830 onward and had a

famous love affair with the French woman writer, Amandine Dudevant,

known by her pen name as Georges Sand (1804-1876). He died

of TB in Paris

at age 39. (There was a beautiful celebration in Paris on the

centenary of his death, summer 1949).

The great emigration was the artistic and political

heart of Poland until the

failure of the second revolt against Russia,

1863-64 and the Austrian grant of self-rule to Galicia,

Austrian Poland,

in 1868.

7. The Revolts of 1846 and 1848.

(A) 1846: In that

year, there was unrest all over Europe. A

series of bad harvests, and especially the potato blight, led to widespread

hunger, and to famine in European countries, not only in Ireland. At the

same time, people in many countries believed it was to time to rise up against

the monarchies and set up democratic republics.

In Poznan province (German: Posen) there was a

conspiracy, led by members of the PDS, to organize a national uprising to free Poland from

foreign rule. However, they were betrayed, arrested, and imprisoned in Berlin.

In the Republic of

Cracow (Polish: Krakow), a few democratic nobles tried to rouse the

peasants to rise up against Austria.

They began the insurrection in February 1846, gathering support from the more

enlightened peasants of the Cracow

region. However, most of the peasants of Austrian Poland (Galicia) were

undernourished because of bad harvests and hated their lords. Therefore, they

believed Austrian declarations that the good Emperor wanted to free them, while

their Polish lords opposed this. Furthermore, the Austrians offered money for

the heads of Polish nobles. This led to the "Galician Slaughter," in

which many nobles and their families were murdered by peasants. The revolt got

out of hand and the Austrians had to put it down. The Republic

of Cracow was abolished and

incorporated into Galicia.

(B) In 1848,

revolts broke out all over Europe. Again,

they started in Paris,

this time with the overthrow of King Louis Philippe in February of that year.

In March, a revolution broke out in Berlin and

the Italians revolted against Austrian rule, Also, there was a revolt in Vienna and a quiet revolution for home rule in Bohemia, while the

Hungarians also demanded home rule. When attacked, they fought for

independence, but lost. (For the Czechs, Slovaks and Hungarians, see lectures

6.7; for the Croats and Slovenes, and other Balkan peoples, see lectures 8, 9).

After the March

revolt in Berlin,

the Prussian Liberals feared Russian intervention, so they allowed the Poles

of Poznan to raise troops. However, Tsar Nicholas I did not move, so

the Prussian and other German Liberals, who met in the Frankfurt Parliament

to discuss what kind of united German state should be established, refused to

grant home rule to the Prussian Poles. A Prussian general and troops were sent

against them and defeated them.

Note that Mickiewicz

led a Polish Legion in defense of the short-lived Roman

Republic in Italy, but it was crushed.

Thus, the "War

of the Peoples" of 1848 failed to liberate the Poles and other peoples

of the Austrian Empire. However, in 1848 the word "Poland" became the shorthand for freedom

all over Europe.

The Crimean War, 1854-56.

This war broke out

when the Russian armies of Nicholas I invaded and occupied the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Walachia

of the Ottoman Empire. [They would soon

form the core of the new Romanian state].The British and French, who did not

want Russia to dominate or

destroy the Ottoman Empire, sent their fleets

to support it. When bilateral negotiations failed, war broke out between the

Russians and the Turks in October 1853. In January 1854, after the Russians

sunk some Turkish ships, British and French warships entered the Black Sea and

their troops - plus some from the Kingdom of Piedmont- Savoy - landed in the Crimea.

The Poles had great

hopes that France and Britain would crush Russia,

so Poland

would regain independence. Mickiewicz rushed to Turkey and tried to raise a

Polish-Jewish legion to serve in the Turkish army, but he died in Instanbul, probably of the plague, in 1855. Even without

his efforts, there were Polish units in the Turkish army, paid by Queen Victoria of England. (Their Turbans, adorned

with Polish eagles, can be see

today in the Polish Institute and Sikorski Musem, London).

Unfortunately for the

Poles, the Crimean War led to a stalemate, and the French Emperor Napoleon III

gave up plans for an armed landing on the coast of Lithuania. At the same time, France and Britain

supported Austria against Russia and had good relations with Prussia, so they were not willing to support an

independent Poland.

Nevertheless, the

fact that Russia

suffered defeat gave some hope to the Poles. They were also encouraged by the

death of Nicholas I in 1855, and by the fact that his successor Tsar

Alexander II began a policy of liberalization not only in Russia proper,

but also in Russian Poland. In 1861, he proclaimed the emancipation of the

peasants in Russia

- but not yet in Russian Poland.

8. Background to the Revolution of 1863-64 against Russia.

(A) Alexander II released many Polish exiles from Siberia.

Most returned to Poland,

many of them to Warsaw,

where they inspired young people with the desire for independence.

(B) In 1856,

Alexander allowed the establishment of the Warsaw Medical Academy and of

the School

of Fine Arts. In

1862, they were followed by the "Main School," which consisted

of the Medical Dept. (the reformed Medical

Academy), and departments

of physics-mathematics, law, and philology-history. This led many Polish

students to come from Russian universities, and they started conspiring for a

revolution.

(C) Count Andrzej Zamoyski (1800-1874,

pron. Zamoyskee), a great landowner, began annual

meetings of landowners to view and discuss agricultural innovations. These

meetings of the "Agricultural Association" turned into political

discussions on how to regain Polish independence and the former eastern

territories of Poland.

However, for the time being, the Agr.Assoc.

followed a policy of "organic work" modeled on

the activities of Poles in post- 1831 Prussian Poland, that is, working for

Polish education and prosperity within the legal limits set by foreign rulers.

However, the War

of Italian Liberation (Risorgimento) and the Austrian defeat there by

French armies (Solferino, 1859), was an

inspiration to Poles. A Polish military academy was set up in Cuneo, Italy.

There was also

ferment in Russian Poland. In late Feb. 1861, there were patriotic

demonstrations in Warsaw and in Wilno (Vilnius), Lithuania.

Russian troops fired on the demonstrators in Warsaw and killed five. The Poles were

outraged, and so was western opinion.

A great Polish

magnate, Alexander Wielopolski (1803-1877,

pron. Wyehlohpohlskee), now came forward with a

moderate program of extending Polish rights in cooperation with the Russian

government. This was accepted by Tsar Alexander II, but Wielopolski

alienated Polish opinion by dissolving Zamoyski's Agr.Assoc. Then, on 8 April 1862, Russian troops fired on a

peaceful demonstration in Warsaw,

killing a hundred people. These two steps turned Polish opinion against Wielopolski and his moderate program.

In summer 1862, the

Tsar's brother, the Grand Duke Constantine, arrived in Warsaw

as the Russian Viceroy for Poland.

It looked as if Tsar Alexander II was trying to repeat the experiment with the Kingdom of Poland. 1815-30. However, three young

Poles tried assassinate the Viceroy. The attempt failed and Wielopolski

had them hanged, which made them martyrs for the Polish cause.

In the meanwhile,

students and others were conspiring to organize a revolt against Russia. They

were called Reds because their program was radical for the time and red

was the color of revolution. The key points of the Red program were:

(a) Revolution in Poland linked to an expected revolution in Russia - where

emancipation had disappointed the peasants, leading to numerous peasant risings

which were expected to lead to revolution.

(b) Abolition of

serfdom in Russian Poland, without compensation for the landlords - who were compensated

in Russia.

(c) Poland would offer the non-Polish peoples of the

former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, that is, Ukrainians, Belorussians,

and Lithuanians, a choice of either union or federation with Poland.

[See: K.Olszer, For Your Freedom and Ours, From the

Manifesto of the National Government of 1863, pp. 73-75.

Note that the Polish

Reds agreed on this program with the exiled Russian revolutionary writer Alexander

Herzen (1812-1870, pron. Hehrtsen),

publisher of the paper Kolokol (The Bell) in London.

The paper was smuggled into Russia,

where it was very widely read by the Russian intelligentsia (educated people).

However, Herzen's support of the Polish revolution

was seen as unpatriotic and alienated his Russian readers.

9. REVOLUTION, 1863-64.

Although the Reds did not plan to revolt until there

was a large scale peasant revolt in Russia - where revolts were

spreading because of peasant dissatisfaction with the terms of their

emancipation - they were forced to act when Wielopolski

ordered selective conscription into the Russian Army in Jan. 1863. He did this

to remove the key conspirators and thus avert a revolt. Therefore, the Reds

published their Manifesto and began the revolt on Jan.22, 1863. (See the

Manifesto in K.Olszer, For Your Freedom and Ours).

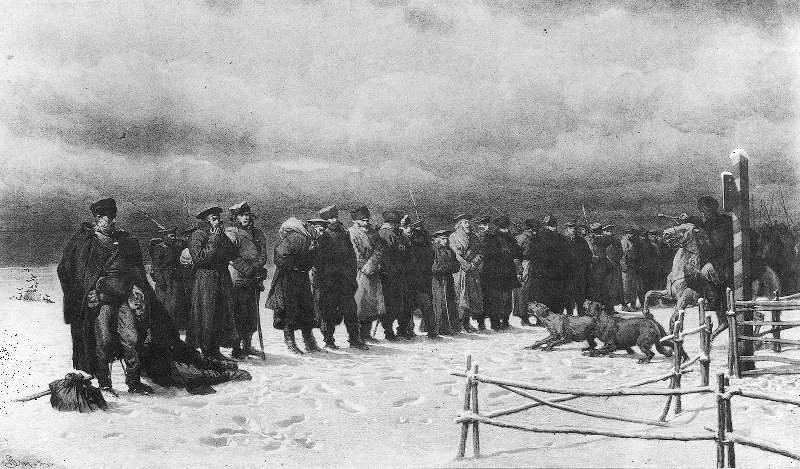

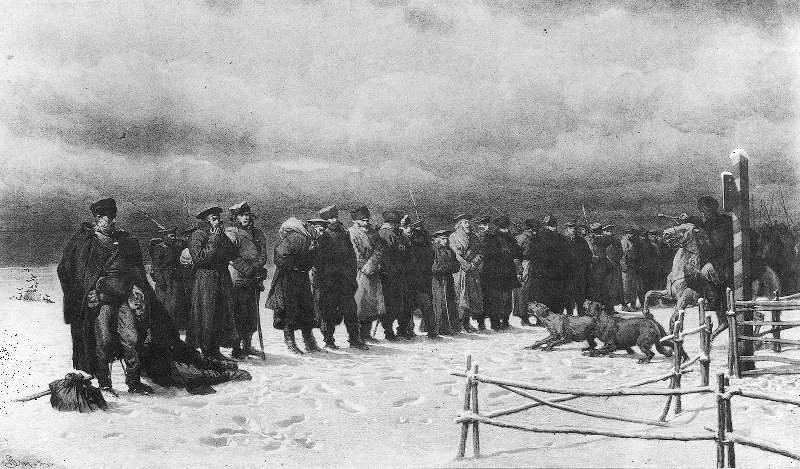

Byelorussian rebels fighting in support of Poland

under K. Kalinowski and Z. Sierakowski

Why the Revolution failed:

(A) There was no widespread peasant revolt in Russia;

(B) There was no help from abroad. The conservative

rebels had counted on help from Napoleon III of France, but he dared not move

because of Prussia and Britain

were opposed.

(C) Prussia - Bismarck - concluded an agreement with Russia to intern any Polish soldiers who crossed

into Prussia.

Historians often denigrate the typical weapon of the Polish peasantry in

1830-31 and 1863-64 - the pike-mounted scythe. However, in the days before

rapidly reloading rifles and artillery guns, a mass of peasants armed with

their pike-scythes could overwhelm a line of infantry or an artillery post. However,

even tens of thousands of peasants armed with this weapon could not prevail

against well trained Russian armies which outnumbered the Poles 10-1 in

1830-31, and even more in 1863-64, when there was no regular Polish army as in

1830-31.

Despite defeat,

Polish national consciousness was strengthened by two factors; (i) Poles came to fight from other parts of Poland; (ii)

the Polish peasants heard of the Reds' Manifesto; therefore, they did not feel

loyalty to Tsar Alexander II when he emancipated them.

The Aftermath.

There was severe

Russian repression, with executions and confiscation of landed estates owned by

participants in the revolt. [One of them was the author's great grandfather on

her mother's side, who escaped to Austrian Poland]. Furthermore, some 50,000

Polish gentry families were deported from former

eastern Poland to Siberia, to be replaced by Russians. There was also russification of the administration, law courts, and

education in both former eastern Poland and former Congress or

Russian Poland. The former Main School in Warsaw

became a Russian university in 1869.

Polish Reaction.

After the failure of

two revolts against Russia

within 34 years, the Polish intelligentsia turned away from armed struggle as

the means of regianing independence. In Russian

Poland, they adopted Positivism, which was really a form of "OrganicWork," that is, work for education and

prosperity. In particular, they worked to educate the peasants. Many young

students and teachers did this secretly, for it was illegal. Indeed, only

Russian schools were allowed and private education was forbidden.

Positivism prevailed

until about 1891, the centenary of the May 3 Constitution, which led to student

demonstrations in Warsaw,

brutally put down by Cossack troops. Nevertheless, with the establishment of

the Polish Socialist Party Abroad in 1892 and

then the Polish Socialist Party (PPS)in Warsaw in 1893, young people began to

conspire again to regain Polish independence.

----------------------------------

Brief Bibliography

Piotr S. Wandycz, The Lands of Partitioned Poland, 1795-1918, Seattle, WA., 1974

and reprints. (Pt. I covers

the period 1795-1830; Pt. II, 1830-1864; Pt. III, 1864-1890; Pt. IV.

1890-1918).

Norman Davies, God's Playground. A History of Poland, New York, 1982.

For works on special topics, see Bibliography: Select

English Language Works on the History of Eastern Europe,

Part I.

Originally

published at http://www.ku.edu/~eceurope/hist557/lect5b.htm

|

|

Anna M. Cienciala

Professor Emerita / The University of Kansas

hanka@ku.edu

B.A. Liverpool, 1952, M.A. McGill, 1955;

Ph.D. Indiana, 1962

20th century Polish, European, Soviet, and

American diplomacy 1919-1945.

Born in the Free City of Danzig (Gdańsk, in Poland after WWII); she attended middle

and high school in England; university studies in England, Canada, and U.S. (B.A.

Liverpool, 1952, M.A. McGill, 1955; Ph.D. Indiana, 1962). She taught at the

University of Ottawa and the University of Toronto before coming to the

University of Kansas in 1965. More info

|

BACK

TO POLISH HISTORY