|

|

A FEW

WORDS ABOUT ADOLF HITLER’S PRIVATE LIBRARY (excerpts from the

book “Hitler’s Private Library” (2010) |

||

|

|

PREFACE: The Man Who

Burned Books HE WAS, OF COURSE, a man known better for

burning books than collecting them and yet by the time he died at age

fifty-six he owned an estimated sixteen thousand volumes. It was by any

measure an impressive collection: first editions of the works of

philosophers, historians, poets, playwrights and novelists. For him the

library represented a Pierian spring, that

metaphorical source of knowledge and inspiration. He drew deeply there,

quelling his intellectual insecurities and nourishing his fanatic ambitions.

He read voraciously, at least one book per night, sometimes more, so he

claimed. “When one gives one also has to take,” he once said, “and I take

what I need from books.” He ranked Don Quixote, along with Robinson

Crusoe, Uncle Tom's Cabin, and Gulliver's Travels, among the great

works of world literature. “Each of them is a grandiose idea unto itself,” he

said. In Robinson Crusoe he

perceived “the development of the entire history of mankind." Don Quixote captured

“ingeniously" the end of an era. He owned illustrated editions of both

books and was especially impressed by Gustave

Dore's romantic depictions of Cervantes's delusion-plagued hero. He also owned the collected works of

William Shakespeare, pub¬lished in German

translation in 1925 by Georg Muller as part of a series intended to make

great literature available to the general public. Volume six includes As You Like It, Twelfth Night, Hamlet,

and Troilus and Cressida. The

entire set is bound in hand-tooled Moroccan leather with a gold-embossed

eagle flanked by his initials on the spine. He considered Shakespeare superior to

Goethe and Schiller… He was versed in the Holy Scriptures, and

owned a particularly handsome tome with Worte Christi, or Words of

Christ, embossed in gold on a cream-colored calfskin cover that even

today remains as smooth as silk. He also owned a German translation of Henry

Ford's anti-Semitic tract, The

International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem, and a 1931 handbook on

poison gas with a chapter detailing the qualities and effects of prussic

acid, the homicidal asphyxiant marketed

commercially as Zyklon B. On his bedstand, he kept a well-thumbed copy of Wilhelm Busch's

mischievous cartoon duo Max and Moritz. WALTER BENJAMIN ONCE SAID that you could

tell a lot about a man by the books he keeps—his tastes, his interests, his habits. The books we retain and those we discard,

those we read as well as those we decide not to, all say something about who

we are. As a German-Jewish culture critic born of an era when it was possible

to be "German" and "Jewish," Benjamin believed in the

transcendent power of Kultur.

He believed that creative expression not only enriches and illuminates the

world we inhabit, but also provides the cultural adhesive that binds one

generation to the next, a Judeo-Germanic rendering of the ancient wisdom ars longa, vita brevis. Benjamin held the written word—printed and

bound—in especially high regard. He loved books. He was fascinated by their physicality,

by their durability, by their provenance. An astute collector, he argued,

could "read" a book the way a physiognomist

deciphered the essence of a person's character through his physical features.

"Dates, place names, formats, previous owners, bindings, and all the

like," Benjamin observed, "all these details must tell him

something—not as dry isolated facts, but as a harmonious whole." In

short, you could judge a book by its cover, and in

turn the collector by his collection. Quoting Hegel, Benjamin noted,

"Only when it is dark does the owl of Minerva begin its flight,"

and concluded, "Only in extinction is the collector comprehended." When Benjamin invoked a nineteenth-century

German philosopher, a Roman goddess, and an owl, he was of course alluding to

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's famous maxim: “The owl of Minerva spreads its

wings only with the falling of dusk," by which Hegel meant that

philosophizing can begin only after events have run their course. Benjamin felt the same was true about

private libraries. Only after the collector had shelved his last book and

died, when his library was allowed to speak for itself, without the

proprietor to distract or obfus¬cate, could the

individual volumes reveal the “preserved" knowledge of their owner: how

he asserted his claim over them, with a name scribbled on the inside cover or

an ex libris bookplate pasted across an entire

page; whether he left them dog-eared and stained, or the pages uncut and

unread. Benjamin proposed that a private library serves

as a permanent and credible witness to the character of its collector,

leading him to the following philosophic conceit: we collect books in the

belief that we are preserving them when in fact it is the books that preserve

their collector. “Not that they come alive in him," Benjamin posited.

“It is he who lives in them." FOR THE LAST HALF CENTURY the remnants of

Adolf Hitler's library have occupied shelf space in climatized

obscurity in the Rare Book Division of the Library of Congress. The twelve hundred

surviving volumes that once graced Hitler's bookcases in his three elegantly

appointed libraries—wood paneling, thick carpets, brass lamps, overstuffed

armchairs—at private residences in Munich, Berlin, and the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden, now stand in densely

packed rows on steel shelves in an unadorned, dimly lit storage area of the

Thomas Jefferson Building in downtown Washington, a stone's throw from the

Washington Mall and just across the street from the United States Supreme

Court. The sinews of emotional logic that once ran

through this collection—Hitler shuffled his books ceaselessly and insisted on

reshelving them himself—have

been severed. Hitler's personal copy of his family genealogy is sandwiched

between a bound collection of newspaper articles titled Sunday Meditations and a folio of political cartoons from the

1920s. A handsomely bound facsimile edition of letters by Frederick the

Great, specially designed for Hitler's fiftieth birthday, lies on a shelf for

oversized books beneath a similarly massive presentation volume on the city

of Hamburg and an illustrated history of the German navy in the First World

War. Hitler's copy of the writings of the legendary Prussian general Carl von

Clausewitz, who famously declared that war was politics by other means,

shares shelf space beside a French vegetarian cookbook inscribed to “Monsieur Hitler vegetarien. ” When I first surveyed Hitler's surviving

books, in the spring of 2001,1 discovered that fewer

than half the volumes had been catalogued, and only two hundred of those were

searchable in the Library of Congress's online catalogue. Most were listed on

aging index cards and still bore the idiosyncratic numbering system assigned

them in the 1950s. At Brown University, in Providence, Rhode

Island, I found another eighty Hitler books in a similar state of benign

neglect. Taken from his Berlin bunker in the spring of 1945 by Albert

Aronson, one of the first Americans to enter Berlin after the German defeat,

they were donated to Brown by Aronson's nephew in the late 1970s. Today they

are stored in a walk-in basement vault, along with Walt Whitman's personal

copy of Leaves of Grass and the

original folios to John James Audubon's Birds

of America. Among the books at Brown, I found a copy of

Mein Kampf

with Hitler's ex libris bookplate, an analysis of

Wagner's Parsifal published in

1913, a history of the swastika from 1921, and a half dozen or so spiritual

and occult volumes Hitler acquired in Munich in the early 1920s, including an

account of supernatural occurrences, The

Dead Are Alive!, and a monograph on the prophecies of Nostradamus. I

discovered additional Hitler books scattered in public and private archives

across the United States and Europe. Several dozen of these surviving Hitler

books contain marginalia. Here I encountered a man who famously seemed never

to listen to anyone, for whom conversation was a relentless tirade, a

ceaseless monologue, pausing to engage with the text, to underline words and

sentences, to mark entire paragraphs, to place an exclamation point beside

one passage, a question mark beside another, and quite frequently an emphatic

series of parallel lines in the margin alongside a particular passage. Like

footprints in the sand, these markings allow us to trace the course of the

journey but not necessarily the intent, where attention caught and lingered,

where it rushed forward and where it ultimately ended. In a 1934 reprint of Paul Lagarde's German

Letters, a series of late- nineteenth-century essays that advocated the

systematic removal of Europe's Jewish population, I found more than one

hundred pages of penciled intrusions, beginning on page 41, where Lagarde calls for the “transplanting" of German and

Austrian Jews to Palestine, and extending to more ominous passages in which

he speaks of Jews as “pestilence." “This water pestilence must be

eradicated from our streams and lakes," Lagarde

writes on page 276, with a pencil marking bold affirmation in the margin.

“The political system without which it cannot exist must be eliminated." ………………………….. Hitler s own library was rapidly

disassembled in the chaos of his collapsing empire. By the time he shot

himself, American soldiers were already picking apart his collections in

Munich. In Hitler's office at the Nazi Party headquarters in the Brown House,

a young lieutenant found the copy of Henry Ford's My Life and Work that Hanfstaengl had

inscribed back in 1924; the lieutenant eventually took the two-volume set,

which "showed evidence of thumbing," back to New York and put it up

for sale at Scribner's Bookstore. At Hitler's Prince Regent Square residence,

war correspondent Lee Miller found Hitler's books partially intact. "To

the left of the public rooms was a library full of richly bound books and

many presentation volumes of signatures from well-wishers," she noted.

"The library was uninteresting in that everything of personal value had

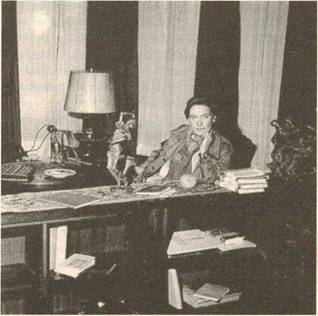

been evacuated: empty shelves were bleak spoors of flight." A photograph

shows Miller seated at Hitler's desk. A dozen or so random books litter the

adjacent shelves—paperbacks, hardcovers, a large,

scuffed picture book of Nuremberg, three early editions of Mein Kampf

in their original dust jackets.

War correspondent

Lee Miller in Hitler's Prince Regent Square residence. Most personal books

had been removed by Hitler's staff. Note copies of Mein Kampf with the original dust

jackets. Four days later, advance troops of the

101st Airborne Division arrived on the Obersalzberg

to find Hitler's Berghof a smoldering ruin. In the

second-floor study, the hand-tooled bookcases had been reduced to ash,

leaving only charred concrete walls and a soot-blackened strongbox, in which

the soldiers found several first editions of Mein Kampf The rest of Hitler's books

were discovered in a converted bunker room. "At the far end were

arranged lounge chairs and reading lamps," an intelligence officer

assigned to the 101st reported. "Most of the books were con¬cerned with art, architecture, photography and

histories of campaigns and wars. A hasty inspection of the scattered books

showed that it [sic] was notably lacking in literature and almost entirely

devoid of drama and poetry." The classified report identifies only three

works by name: Genesis of the World War,

by the American revisionist historian Harry Elmer Barnes, Niccolo

Machiavelli's The Prince, and the

critiques by the eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant. The handsomely bound tomes with their

distinctive bookplates became the totem of choice for the victorious

soldiers. Newsreel footage records American soldiers picking through Hitler's

book collection. One sequence shows a soldier opening a large volume to

reveal the Hitler ex libris as the camera zooms in

for a close-up; in another, several men emerge from the bunker with stacks of

books under their arms. In the weeks that followed, the Berghof

collection was picked apart book by book. By May 25, when a delegation of

U.S. senators arrived on the Obersalzberg, they had

to content themselves with albums from Hitler's record collection. Not a

single book remained. In those same weeks, Hitler's book

collection in Berlin was also disassembled. At nine o'clock on the morning of

May 2, thirty-six hours after Hitler's suicide, a Soviet medical team entered

the nearly abandoned Fuehrerbunker.

They reemerged an hour later waving black lace

brassieres from Eva Braun's wardrobe and carrying satchels filled with

diverse souvenirs, including several first editions of Mein Kampf Successive waves of plundering

followed. When Albert Aronson arrived in Berlin as part of the American

delegation sent to negotiate the joint occupation of the city, his Soviet

hosts took him on a tour of Hitler's private quarters and as a courtesy let

him take an unclaimed pile of eighty books. In those same weeks, the entire

Reich Chancellery library—an estimated ten thousand volumes—was secured by a

Soviet “trophy brigade" and shipped to Moscow and never seen again.[1]

The only significant portions of Hitler library's to survive intact were the

three thousand books discovered in the Berchtesgaden salt mine, twelve

hundred of which made it into the Library of Congress. The rest appear to

have been "duped out" in the process of cataloguing the collection. Thousands more lie in the attics and

bookshelves of homes of veterans across the United States. Occasionally,

random volumes find their way to the public. Several years ago, a copy of

Peter Maag's Realm

of God and the Contemporary World, published in 1915, with "A.

Hitler" scrawled on the inside cover, was discovered in the fifty-cent

bin of a local library sale in upstate New York. Following Aronson's death,

his nephew donated the eighty books from the Fuehrerbunker to Brown

University. In the early 1990s, Daniel Traister,

head of the rare book collection at the University of Pennsylvania, was given

a biography of Frederick the Great along with several Berghof

trophies. An accompanying note read "Dan, you wouldn't believe how much

money people want to offer me for these things. So far, I haven't met one

whom I want to have them. Here: destroy them or keep them as you wish." A few years ago, I received a similar note

after writing an article on Hitler's library for The Atlantic Monthly. A Minnesota book dealer had inherited a

Hitler book her mother had purchased at auction in the 1970s. Initially

fascinated by the acquisition, the mother suffered a double bite of

conscience: she was uncomfortable with profiting from a Hitler artifact and

was equally uneasy about the motivations of a potential purchaser. After the

mother's death, her daughter inherited both the book and the dilemma. Having

read my article, and sensing that my interests were purely academic, she offered

me the book at cost. A week later, Hitler's copy of Body, Spirit and Living Reason, by Carneades,

arrived in a cardboard box. The treatise was in remarkably good

condition, a hefty tome bound in textured linen with leather triangles on each

corner and a matching leather spine with title and author embossed in gold.

The linen was partially frayed and the leather was scuffed in places, but

otherwise the volume was flawless. Opposite the Hitler ex libris,

a typewritten note had been tipped into the binding recording the volume's

provenance: This volume was taken from Adolph [sic]

Hitler's personal library located in the underground air-raid shelter in his

home at Berchtesgaden. It was picked up by Major A. J. Choos

as a souvenir for Mr. E. B. Horwath on May 5,1945. For several years, Body, Spirit and Living Reason haunted the bookshelves of my

Salzburg apartment until I, too, grew uncomfortable with its presence. Like

the Pennsylvania veteran and the Minnesota book dealer, I had no interest in

profiting from the volume and had serious concerns about its further

disposition. I ultimately resolved the dilemma by donating the volume to the

Archive of the Contemporary History of the Obersalzberg

in Berchtesgaden, a private repository established by a resident archivist to

preserve the history of the town, including this dark chapter.

The Hitler Library

in the rare book and manuscript division at the Library of Congress, as photographed

in the 1970s. After spending nearly a decade behind a

glass case in Hitler's second- floor Berghof

study—a silent witness to his daytime meetings and late-night reading—the Carneades volume had found its way back to Berchtesgaden,

where its journey had begun nearly seven decades earlier. Indeed, habent suafata libelli. APPENDIX A From This Is the Enemy, by Frederick Oechsner, 1942 I FOUND THAT [HITLER'S] PERSONAL LIBRARY,

which is divided between his residence in the Chancellery in Berlin and his

country home on the Obersalzberg at Berchtesgaden,

contains roughly 16,300 books. They may be divided generally into three

groups: First, the military section containing some

7,000 volumes, including the campaigns of Napoleon, the Prussian kings; the

lives of all German and Prussian potentates who ever played a military role;

and books on virtually all of the well-known military campaigns in recorded history. There is Theodore Roosevelt's work on the

Spanish American War, also a book by General von Steuben, who drilled our

troops during the American Revolution. [Werner von] Blomberg,

when he was war minister, presented Hitler with 400 books, pamphlets and

monographs on the United States armed forces and he has read many of these. The military books are divided according to

countries. Those which were not available in German Hitler has had

translated. Many of them, especially on Napoleon's campaigns, are extensively

marginated in his own handwriting. There is a book

on the Gran Chaco dispute [the 1932-35 war between Paraguay and Bolivia] by

the German General [Hans] Kundt, who at one time

(like Captain Ernst Rohm) was an instructor of troops in Bolivia. There are

exhaustive works on uniforms, weapons, supply, mobilization,

the building-up of armies in peacetime, morale and ballistics. In fact, there

is probably not a single phase of military knowledge, ancient or modern,

which is not dealt with in these 7,000 volumes, and quite obviously Hitler

has read many of them from cover to cover. The second section of some 1,500 books

covers artistic subjects [such] as architecture, the theater, painting and

sculpture, which, after military subjects, are Hitlers chief interest. The books include works on surreal¬ism and Dada-ism, although Hitler has no use for

this type of art. One of his ironical marginal notes could be

roughly translated: "Modern art will revolutionize the world? Rot!"

In writing these notes Hitler never uses a fountain pen but an old-fashioned

pen or an indelible pencil. In drawers beneath the bookshelves he has a

collection of photographs, drawings [of] famous actors, dancers, singers,

both male and female. One book on the Spanish theater has pornographic

drawings and photographs, but there is no section on pornography, as such, in

Hitler's library. The third section includes works on

astrology and spiritualism pro-cured from all parts of the world and

translated where necessary. There are also spiritualistic photographs, and,

securely locked away, the 200 photographs of the stellar constellations on

important days in his life. These he has annotated in his own handwriting and

each has its own separate envelope. In this third section there is a

considerable part devoted to nutrition and diet. In fact, there are probably

a thousand books on this subject, many of them heavily marginated,

those marginal comments including the vegetarian observation: "Cows were

meant to give milk; oxen to draw loads." There are dozens of books on

animal breeding with the photographs of stallions and mares of famous name.

One interesting psychological angle here is that where stallions and mares

are shown on opposite pages, many of the mares have been crossed out in red

pencil as merely inferior females and unimportant compared with the stallion

males. There are some 400 books on the

Church—almost entirely on the Catholic Church. There is also a good deal of

pornography here, portraying alleged license in the priesthood: offenses such

as made up the charges in the immorality trials which the Nazis conducted

against priests at the height of the attack upon the Catholic Church. Many of

Hitler's marginal notes on this pornographic section are gross and uncouth.

Some pictures show Popes and Cardinals reviewing troops at moments in

history. The marginations here are: "Never

again" and "This is impossible now," showing that Hitler

proposes that the princes of the Church shall never again be allowed to gain

political positions in which they can command armies and otherwise exercise

temporal pow¬ers. Hitler is himself a Catholic,

though not a practicing one. Some 800 to 1,000 books are simple, popular

fiction, many of them pure trash in anybody's language. There are a large

number of detective stories. He has all of Edgar Wallace; adventure books of

the G. A. Henty class; love romances by the score,

including those by the leading roman¬tic sob sister

of Germany, Hedwig Courts-Mahler, in which wealth and poverty, and strength

and weakness are sharply contrasted and in which honor and chastity triumph

and the sweet secretary marries her millionaire boss. All of these flaming

volumes are in neutral covers so as not to reveal their titles. Hitler may

read them, but he doesn't want people to know that he does. Among Hitler's favorites is a complete set

of American Indian stories written by the German, Karl May, who had never

been to America. These books are known to every German youngster, and

Hitler's fondness for them as bedside reading suggests that he, like many a

German thirteen-year-old, has gone to sleep with the exploits of "Old Shatterhand" reeling through his brain. Hitler's

set, which was presented to him by Marshal Goering, is expensively bound in

vellum and kept in a special case. They are much thumbed and read and usually

one or two may be found in the small bedside bookcase with its green curtain

in Hitler's bedroom. Sociological works are strongly represented

in the library, including a unique book by Robert Ley,

written in 1935, on world sociological problems and solutions. This book

never was circulated. Six thousand copies were printed, 5,999 were destroyed;

the single remaining copy is Hitler's. The reason: all books and pamphlets on

National Socialism have to be submitted to a special Party commission before

being released for publication, and books by prominent Nazi individuals have

to be shown to Hitler himself The book, by Ley, a

notorious idolater, so idealized Hitler that even he couldn't stomach its

being published. Another suppressed book in Hitler's library

is Alfred Rosenberg's work on the proposed Nazi Reich-Church, of which today

there are only twelve copies in proof, although typewritten carbon copies of

some sections are known to exist and in mysterious ways to have circulated as

far as the United States. In earlier days, when he had time, Hitler

used to bind his own dam¬aged books. Hitler's own

best-seller, Mein Kampf

has yielded him a fancy fortune, estimated by German Banking circles to be

about 50,000,000 Reich mark ($20,000,000 at official

rates). With part of this sum, Hitler has amassed a collection of precious

stones valued at some 20,000,000 Reich marks, which he keeps in a special

safe built into the wall of his house at Berchtesgaden. The stones were bought for him in various

parts of the world by his friend Max Amann, head of

the Nazi publishing firm the Eher Verlag, in which Hitler has an interest. It was Hitler who put Max Amann in

charge of the Eher Verlag,

and it has turned out to be a lucrative job; Amann's

own fortune today is estimated by bankers at around 40,000,000 Reich marks.

With absolute autocratic control over all publishing enterprises in Germany,

it is no wonder that the Nazi Eher Verlag snowballed into a phenomenally profitable

enterprise for everybody connected with it, including Adolf Hitler. The Reich

Chancellor has never found it necessary to use his official salary, a large

part of which he turns over to charity. Among the books in Hitler's library is one

volume covering a field in which he has always shown particular interest:

namely, the study of hands, including those of as many famous people

throughout the ages as could be procured. Hitler, in fact, bases a good deal

of his judgment of people on their hands. In his first conversation with some

personality, whether political or military, German or foreign, he usually

most carefully observes his hands—their form, whether they are well cared

for, whether they are long and narrow or stumpy and broad, the shape of the

nails, the knuckle and joint formation and so on. Various generals and

diplomats have wondered why Hitler sometimes, after starting a conversation

in a cordial and friendly way, became cool as he went along, and often closed

the discourse curtly or abruptly without much progress having been made. They

learned only later that Hitler had not been pleased by the shape of their

hands. |

|

|