|

|

Excerpts from the book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written

and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth ,

K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited

by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Russia (pp.

152-157, 231-234, 24-25, 51, 93, 114 and 148) Heraldry developed late in Russia. In the

western part of the country the nobility, being influenced by Poland, began

to assume armorial bearings during the course of the fifteenth century, but

further to the east, not until the following centuries. Devices were used on

seals and as ornaments but were never used in Russia as heraldic military

symbols or even for tournaments. The result has been that the divisions of

the shield and other simple heraldic charges, which in Western Europe are so

typical of the earliest heraldry, are literally non-existent in Russian arms.

Other charges, such as animals, were as a rule neither stylised nor por¬trayed in heraldic form, as is normal in Western

Europe, but were shown in true form, sometimes even in natural surroundings,

so that they look more like illustrations in a book on zoology than coats of

arms. In 1472 Ivan III (1462-1505) married

Sophia, niece of the last ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire, which had fallen

when the Turks conquered Constantinople (Byzantium) in 1453. Ivan III

regarded himself as the heir to the Byzantine Empire and emphasised this by

assuming the title of Czar (a derivative of the

name and style Caesar), and taking the Byzantine double-headed eagle as his

device. Yet an official description of the double-headed eagle as the arms of

the Russian Czars is not found until the close of

the seventeenth century, when it was given new form and was proclaimed with

the arms of thirty-three other realms and principalities which included the

complete title of the Czars. This was done with the

collaboration of an Imperial German herald who had been summoned by the Czar. At about the same time a register of Russian noble

armorial bearings was compiled.

806. The crown of

Ivan the Terrible, sixteenth century. Peter the Great (1689-1725), who worked

hard to introduce Western European ideas and institutions into his kingdom,

took an active interest in heraldry. In 1722 he established a government

department for heraldry directed by a 'master of heraldry', among whose

duties was the creation of armorial bearings for all noble families that had

none, and for all the officers of the army and navy. The 'vice-master of

heraldry' was an Italian (Francesco Santi / Ed.) whose special task it was to design arms

for Russian provinces and towns. He produced in all 137 such coats of arms,

and the influence of French heraldry was very noticeable here. Heraldic

matters became so important during this period that the Imperial Academy of

Arts and Science invited a German professor in 1726 to give a lecture on

heraldry.

There had from early times been many

princely families in Russia, those who were the descendents of Rurik, who was

the ruler of Novgorod 862-79 and was regarded as the founder of the Russian

realm, and those whose ancestors were princes of Lithuania and Georgia or of

Tartar origin. In 1707 Peter the Great made a complete innovation by raising

his favourite Alexander Menschikov to the rank of

titular prince. And this move, promotion to the aristocracy by grant of

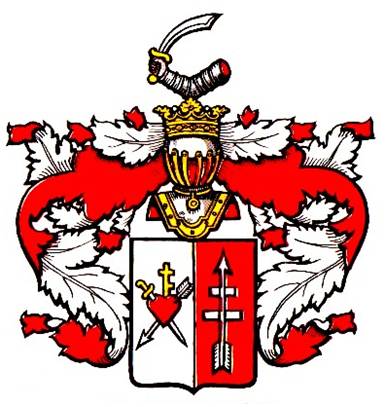

letters patent, was continued to an even greater extent by later rulers. Under Peter the Great's

daughter Elizabeth (1741-61) the Office of Heraldry issued 200 patents of

nobility, some of them to the soldiers who had helped her to power (see Fig.

830), and up to 1797 patents of nobility giving a right to armorial bearings

were granted to 355 persons with no previous title, as well as to

thirty-seven barons and counts.

Coats of arms were as a rule depicted on a

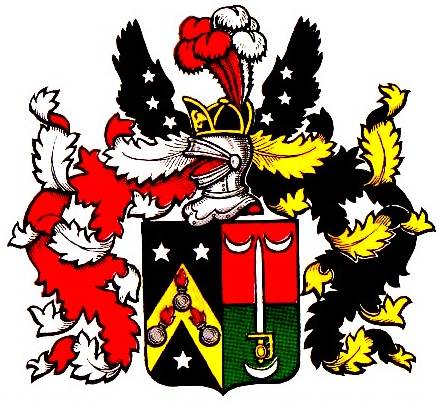

shield known as 'French' (Figs 814 and 815). People newly raised to the

aristocracy bore a helmet with raised visor in profile (Fig. 812), the old

nobility a barred helmet affronty, sometimes with a

coronet (Figs 274 and 815). There were other coronets for barons (Fig. 813)

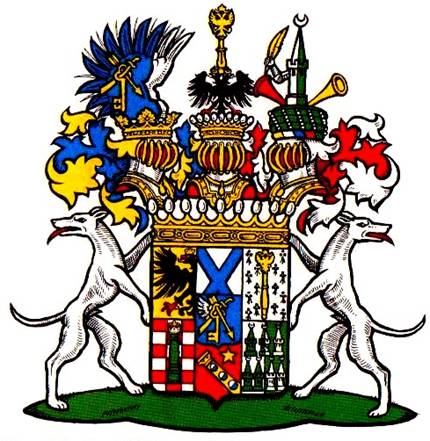

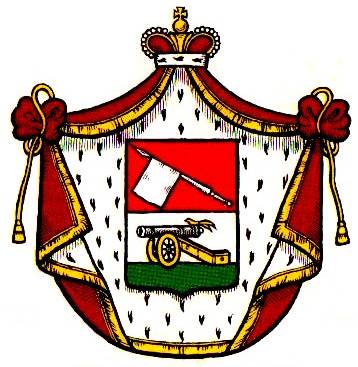

and counts (Fig. 816). Princes had a right to a robe of estate and a prince's

crown (Fig. 814). The arms of the ancient princely families were often shared

by several branches with different names. The Princes Bariatinsky,

who descended from Rurik and the old princes of Kiev, bore the arms of Kiev

(see Fig. 824) together with those of Tchernigov (Fig. 814, also Figs 819 and 820).

The crest was often the main charge

repeated. Occasionally three plumes or vambraced

arm with sword might be used instead. At the close of the eighteenth century the

Emperor Paul (1796—1801) ordered the registration and proclamation of all

Russian coats of arms borne by the aristocracy of the following six

categories: 1. Nobility without title granted a patent

of nobility by the Czar. 2. Noblesse d'epee,

i.e. officers in the army and navy who had reached the rank of colonel and

above. 3. Noblesse du cap, i.e. government

officials who had reached a rank equivalent to colonel. 4. Foreign nobility who had become

naturalised Russians. 5. Nobility already titled. 6. The old aristocracy, i.e. who were noble

before 1685. The first volume of this work appeared in

1798, but ten others that were planned were never printed, and in any case

the work was incomplete. Before publication all armorial bearings were to. be ratified by the Office of Heraldry and by the Czar himself, and since many of the families did not wish

to submit to such an investigation they did nothing about it. Similar works were planned for Russian

Poland and the Ukraine. Here too the heraldic authorities demanded that a

coat of arms should be ratified before it could be used or proclaimed, but

this was never put into effect. (Annexed

by Russia at the end of the eighteenth century only, Poland and Ukraine had

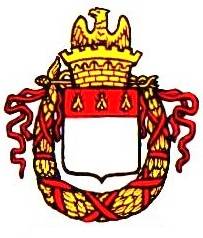

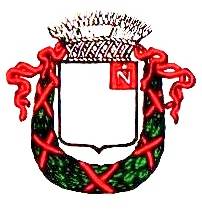

had their own heraldic system long before the events described / Ed.) In 1780 all towns of a certain size which

had no armorial bearings were ordered to assume one, and this again had to be

confirmed by the Czar. Regional capitals as a rule

used the same coat of arms as the region. The other towns used it as a chief

(Fig. 67) in their own bearings. In 1857 this was changed to a canton (Fig.

71), and it was at this time, perhaps in imitation of Napoleonic heraldry

(see Figs 487 and 489), that a system was introduced of mural crowns, gold,

silver and red, with varying numbers of crenellations

depending on the size of the population of the town and its administrative

position, historical importance and so on. Moscow and St Petersburg were

allowed to use the imperial crown (Figs 823 and 825) as well as the sceptre,

the ribbon of the Order of St Andrew and other items.

During the same period it became customary

to frame a civic coat of arms with a wreath of foliage or two green branches

or ears of corn. It seems probable that the wreath of corn bound with ribbon

in the arms of the Soviet Union - since copied by nearly all the communist

states - is a continuation of this practice from Czarist

times. The Russian Revolution of 1917 meant of course an end to all family

arms.

National arms on the other hand continued

to an even greater extent, although in a different form. The Czarist double-headed eagle disappeared and the hammer and

sickle, symbol of the industrial and agricultural classes, took its place. In

the arms of the Soviet Union the hammer and sickle are placed with the globe

as background, and for the people of the world the red star of the Soviet

heralded a new dawn, a fact made comprehensible to all by its composition (click here

for the Soviet and communist symbols). The position of civic heraldry today is not

yet clear, but it certainly arouses interest. In recent years numerous publications

with illustrations and information about the old civic arms from before 1917

have appeared in the Soviet Union, and it is quite possible that those which

do not contain Czarist or religious devices, but

are politically neutral, such as Figs 831 and 832, may be adopted once again. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||