|

|

Excerpts from the book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written

and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth , K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited

by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Germany and Austria (pp.

94-111, 202-206, 7, 9, 49, 148 and 172) In the year 962 the German King Otto the

Great was crowned emperor by the Pope, and this marked the beginning of the imperium which was later given the name of the Holy Roman

Empire of German Nation. It lasted until 1806, when Emperor Franz II

abdicated. In 1804 however he had also assumed the title of Emperor of

Austria, and during the years 1804-6 he was thus both German and Austrian

emperor. The Austrian empire continued until 1918 but it was superseded by

Prussia in political power, and in 1871 the King of Prussia was elected

German emperor as William I. These events were of great importance even

beyond the frontiers of Germany and Austria, because the Holy Roman Empire

and the Austrian empire comprised far more countries than these two. Wholly

or in part, permanently or periodically, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Savoy,

Northern Italy, large areas of the Balkans, Hungary, Bohemia and large parts

of Poland belonged to one or the other of these German- speaking empires, and

this has left its mark on the heraldry of these countries.

All three empires mentioned took the eagle

as their heraldic ensign. In ancient Rome the eagle symbolised Jupiter, and

it was no doubt on the Roman pattern that the emperors took the eagle as

their device (see Figs 11 and 12). An eagle with two heads was known from the

Byzantine Empire, and from the beginning of the fifteenth century the custom

was established that the ordinary eagle should be the device of the German

king before he was crowned emperor, while the double- headed eagle would be

the ensign of the crowned emperor (see below).

But there were many exceptions to this rule.

Free cities, also called imperial cities,

i.e. cities owing allegiance only to the emperor, emphasised this by having

the imperial eagle charged with an inescutcheon of

their own coat of arms, or by bearing the eagle by itself (Fig. 538). Other

combinations also occur - see Fig. 606.

In hundreds of Italian coats of arms there

is an 'imperial chief', or capo dell’ impero, as a

declaration of political allegiance (Fig. 718), and as a sign of favour

certain princes of the Holy Roman Empire Were given the right by the emperor

to superimpose their own arms on the imperial eagle (Figs

792 and 884). When the Austrian empire was established in

1804, the double- headed eagle was continued (Fig. 567), but when the new

German empire was founded in 1871, an eagle with only one head was chosen as

its emblem, probably to emphasise the distinction. It appeared black on a

yellow field. On its breast it bore a shield with the arms of Prussia, also

an eagle, but black on a white field (Fig. 492; the red bordure of this coat is

a difference for the crown prince).

When the Weimar republic was set up in

1918, the old German eagle was retained as an emblem, although in a modernised

form, and this was adopted by West Germany, the Bundesrepublik

Deutschland, after the Second World War (Fig. 494). The colours black, red

and yellow in the coat of arms are the same as those of the present German

flag and they originate from the German wars of liberation against Napoleon

at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In 1919 the Republic of Austria took as its

arms an eagle with only one head as the background for a red shield with a

white fess (Fig. 570). This shield stems from the arms of the family of

Babenberg which ruled in Austria up to 1246; after that time its coat of arms

gradually developed into the arms of Austria. Instead of the sceptre, sword

and orb (see Fig. 567) the republican eagle holds a sickle and a hammer and is

ensigned with a mural crown, these three things

symbolising the farmers, the industrial workers and the bourgeoisie. After

the liberation from Nazi Germany in 1945 the broken fetters around the

eagle's claws were added.

570. Arms of the

Republic of Austria. 1945. In the Holy Roman Empire, as elsewhere, the

oldest coats of arms were self-assumed, but from the close of the fourteenth

century emperors began to grant arms, as time went on mostly through

specially appointed officials called Hofpfalzgrafen

or Pfalzgrafen, (literally translated 'palace

counts') (in this connection the word has nothing to do with the principality

of Pfalz (the Palatinate) on the Rhine). Certain

very noble families, including the Tyrolean branch of the Archdukes of

Austria, were hereditary 'palace counts’, but there were also many others. In

time the king only granted arms personally to cities and the like. Family

coats were dealt with through the 'palace counts', whether for commoners (the

great majority) or for nobles. When raised to the nobility the recipient had

the arms which he may have possessed already augmented by the addition of new

charges or quarterings. The name for this was Wappenbesserung, but according to modern taste the result

was nearly always a coat of arms that was heraldically less satisfactory. In 1702 Prussia established a government

office on French lines which also had to deal with the heraldry of the

country, especially civic arms, and in 1855 this office became the Koniglich Preussisches Her olds

amt, which also dealt with ennoblement etc. After the First World War this

office was done away with and its archives transferred to the Prussian

Ministry of Justice; this is now in Merseburg in

East Germany. Bavaria in 1818 created the office of Reichsherold. In 1902 Saxony instituted the Kommissariat fur Adelsangelegenheiten,

and from 1912 until 1918 patents of arms were also

granted to the middle classes. Such documents of this commissariat that have

survived the Second World War are to be found among the State archives in

Dresden. In Wuerttemberg the Ministry for Foreign Affairs assumed

responsibility for questions concerning nobility and heraldry. In Austria this was done by the Ministry of

the Interior. Its documents, the so-called Gratialregistratur,

are kept today among the Austrian State archives in Vienna. After the First World War the aristocracy

in both Germany and Austria was abolished. Nevertheless it is permissible in

Germany to use noble titles and styles such as von, as these were generally

made part of the family name by the Republic of Weimar, though in Austria it

is a punishable offence to use any form of noble title. Nowadays it is characteristic of both

Germany and Austria that simple coats of arms are preferred to more complicated

ones. Many families of ancient lineage have gone back to using their original

plain arms, often designed in mediaeval style (Figs 525-7), instead of the

composite arms with their many quarterings and

helmets, supporters etc. which their ancestral arms had gradually

accumulated. But whether it is a good thing to have a coat of arms made up in

a style previous to that of the patent of nobility is quite another question,

particularly if it contains a charge, such as a

cannon, which belongs to a subsequent period.

The standard form of a German coat of arms proper

to the nobility is nowadays as is shown on p. 102: shield and barred helmet

with or without coronet, possibly with a medallion around the neck, and with

a crest and mantling.

521. Arms of the family

of Zeppelin, of which the pioneer of airships. Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin

(1838-1917), was a member.

530. Arms of the countly family of von Spee, of

which Admiral Maximilian von Spee (1961 -1914) was

a member. It was during the

late Gothic period that the custom began of marshalling several escutcheons

on one shield and using more than one helmet.

531. Arms of the

baronial family of von Richthofen. of which the famous flying ace of the first World War. Manfred

von Richthofen (1892-1918). was

a member. Some titled noble families in Germany have supporters, others do

not and there exist no definite regulations regarding this.

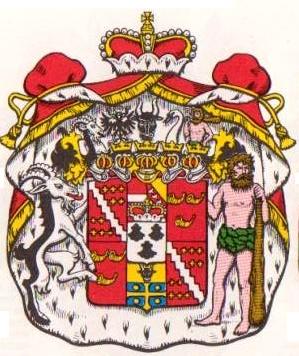

580. Arms of Baron

Rothschild. 1822. The inescutcheon (9 a pun on his name. 'Rothschild' meaning

'red shield'. (The red shield was originally the sign of the house where the

family lived.) The Austrian eagle appears in the first quarter. The hand

holding the arrows in the second and third quarters is no doubt meant to

symbolise strength through solidarity and unity. Motto: 'Unity. Integrity,

Industry’. Many of the aristocratic arms depicted in

this book have a coronet set above the shield with a helmet or helmets above

it (Figs 521, 530, 531 and 580). This was how coats were designed in earlier

times, e.g. in letters patent for armorial bearings, but nowadays there is an

in-clination to get away from such combinations and

either a coronet on its own or a helmet with its appurtenances only is

preferred. Supporters and mottoes are borne mostly by the higher nobility,

but not all of them use them. The custom of having two or more helmets goes

back to the fifteenth century. Noble families, with their armorial bearings

composed of many quarterings,

wanted to have, if possible, an equivalent number of helmets (see Figs 55 and

575).

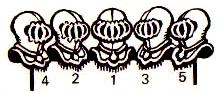

55. The order of

precedence with five helmets

575. Arms of an

Austrian prince, the statesman Klemens von

Metternich (1773-1859). The earliest arms of non-aristocratic

families are known in Germany from the thirteenth century. Throughout the

centuries new families have assumed coats of arms, and still do, without

interference from any authority. Added to these are the thousands of armorial

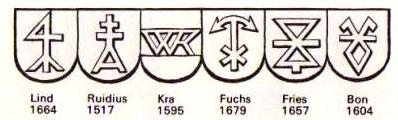

bearings of commoners which since about 1400 have been granted by the Pfalz-grafen. Many of these escutcheons contain ciphers

(see p. 104), but these are rarely included in noble arms. Mottoes are not

customary. The standard form of a German coat of arms for a commoner is

nowadays shield and tournament helmet, with or without wreath, with crest and

mantling (see Figs 550, 552, 557 and 562); the barred helmet with crest

coronet is also found.

During the

Renaissance the chanceries of the various countries mostly used the barred

helmet (see p. 18) for the arms of the nobility, in contrast to the

tournament helmet for the non-aristocratic (as above). But many of the latter

for that very reason bore the barred helmet. And many noblemen developed a

preference for the tournament helmet because of the fact that it was an

earlier type.

551. It gradually

became the custom to set the cipher on a shield. Only a few of these 'arms'

were coloured.

People in Germany are more concerned about

'family arms', Familienwappen, than are people in

Western and Southern Europe and the British Isles, and the principle of individual

members of a family varying their arms is usually foreign to German heraldic

ideas. But differencing does occur in a form unlike that in Great Britain and

France. Branches of the same family of high rank can difference their arms by

various combinations of quarterings, and among the

families of commoners we find differences made by a change in crests or

tinctures (Fig. 552). The German Grown Prince differenced his arms from those

of the Emperor with a red bordure.

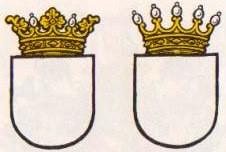

There is at the present day a great

interest in civic heraldry. New civic arms are constantly being designed and

in this connection various forms of mural crown have come into use (Figs 516,

and 522). In earlier times an attempt was made to establish a social scale of

mural crowns, including a special one for the seat of a reigning monarch, but

this did not catch on. Since the mural crown is a comparatively new

phenomenon in heraldry, it should not be used in conjunction with arms which

have been designed in an earlier style. Civic heraldry also makes use of more

traditional coronets (see Figs 270,518,519 and

560).

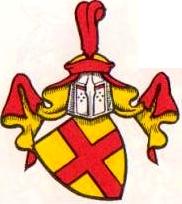

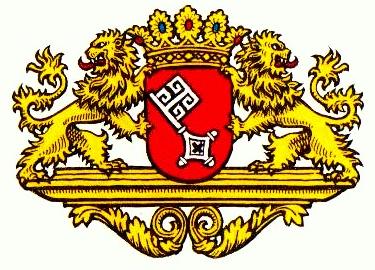

270. Arms of the

Hanseatic town of Bremen.

In West Germany it is usual today for the

authority responsible for internal affairs in each federal state to grant and

confirm civic arms. Family arms are a completely private matter, although

they enjoy a certain amount of legal protection under Paragraph 12 of the

Federal Law. There are various heraldic societies in

West Germany, the most important being as follows: Der Herold, 1 Berlin 33 (Dahlem),

Archivstrasse 12-14, West Berlin; Zum Kleeblatt, Hannover-Kirchrode, Forbacherstrasse 8 and Wappen-Herold, 1 Berlin 31, Tharandter Strasse 2, West

Berlin. In Austria there is the Adler Society, Haarhof 4 a, Vienna 1. MORE ILLUSTRATIONS

(GERMANY)

496. Arms of the

statesman Otto von Bismarck (1815-98) as Prussian prince.

.

MORE ILLUSTRATIONS

(AUSTRIA) .

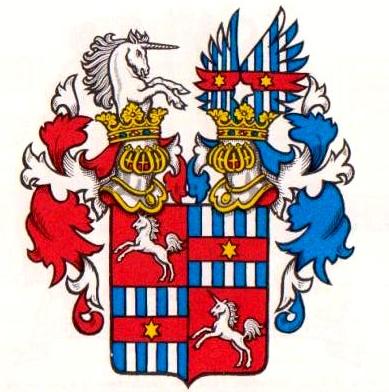

584. Arms of a

hereditary knight Ritter von Liszt of Hungarian descent, the family of the

composer Franz Liszt (1811-86). From the time of

the reign of Charles VI (1711-40) to the collapse of the Empire in 1918

hundreds of hereditary knights were created, nearly all of whom bore two

helmets above the coat of arms.

590. Arms of the

Austrian Oberstfeldarzt (Surgeon General) Matthaeus von Mederer und Wuthwehr, raised to the nobility by

Emperor Joseph II in 1789. . |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||