|

|

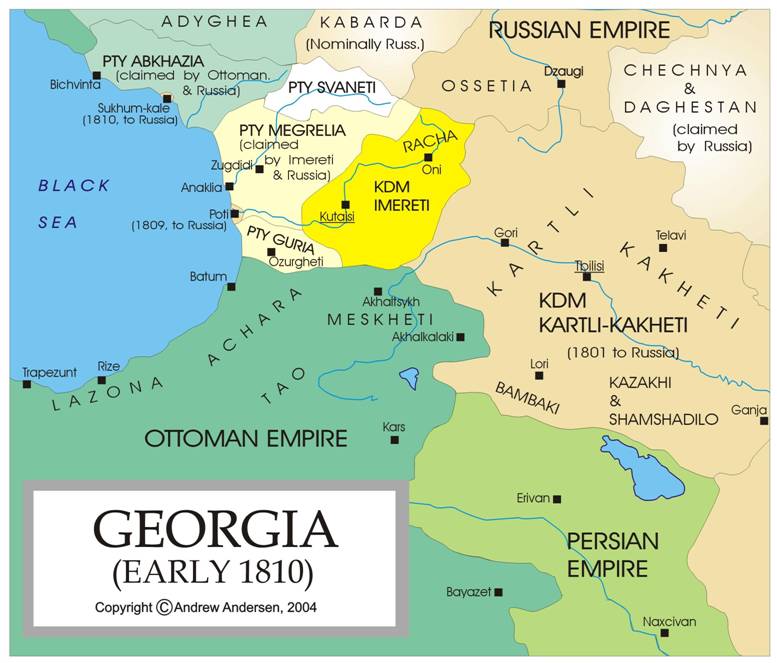

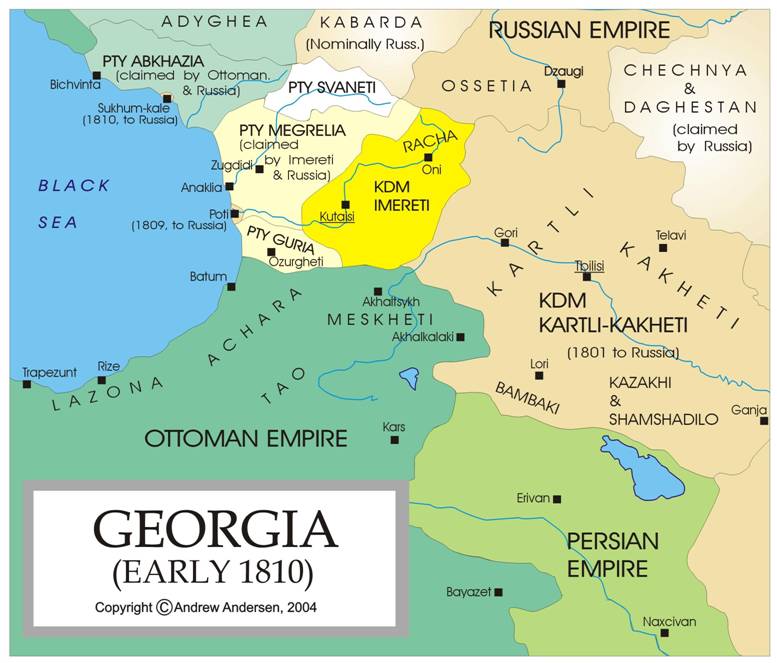

Following the abolition of the Bagratid monarchy of

Kartlo-Kakheti in Eastern Georgia, the liquidation of the branch of the

dynasty ruling in Western Georgia was only a

matter of time. King Solomon II of Imereti defended his independence as long

as he was able. Taken under Russian suzerainty in 1804, Solomon later

revolted and was deposed and captured by armed force in 1810. The smaller

independent principalities of Western Georgia

were gradually absorbed into the administrative framework of the Caucasian

Viceroyalty. Guria was taken over in 1829, Mingrelia in 1857, Svaneti in 1858

and Abkhazia in 1864.

Subjugation of Western

Georgia

Prince Tsitsianov, who

succeeded Knorring as

commander-in-chief,

rapidly extended Russia's

grasp on Transcaucasia. He saw the urgency

of securing as rapidly as possible the entire area between the Black Sea and the Caspian. From his headquarters in Tbilisi, he turned his

attention westwards to Imereti. Western Georgia

was at this time torn by a feud between King Solomon II of Imereti and his

nominal vassal, the semi-independent prince-regent or Dadian Grigol of

Mingrelia. One of Grigol Dadian's predecessors had sworn fealty to the Tsar

of Russia as long ago as 1638. Now, in 1803, his country was taken under

direct Russian suzerainty. In contrast to the situation in Eastern

Georgia, the local administration was left to the princely

house, which retained control under nominal Russian supervision until the

dignity of Dadian was finally abolished in 1867. With his principal vassal

and foe now under Russian protection, King Solomon of Imereti felt it wise to

feign submission. His dominions also were in 1804 placed beneath the imperial

aegis, under guarantees similar to those given to the Dadian. However,

Solomon remained at heart bitterly opposed to his foreign overlords, and his

court at Kutaisi

was a hot-bed of anti-Russian intrigue. ..

Under Tsitsianov's successors, the war against Persia and Turkey continued with varying

success and great ferocity. On the Persian front, Derbent and Baku were at last annexed in 1806, though a second

attack on Erivan in 1808 ended in another

costly failure. In Western Georgia, the Russians kept up their pressure on

the Turks, from whom they took the Black Sea port

of Poti in 1809, Sukhum-Kaleh on the

coast of Abkhazia in 1810, and the strategic town of Akhalkalaki

('New Town') in south-western Georgia

in 1811.

Click on the map for better resolution

King Solomon II and Napoleon Bonaparte

The remaining independent princes of Western

Georgia hastened to accept Russian suzerainty. In 1809, Safar

Bey Sharvashidze, the Lord of Abkhazia, was received under Russian protection

and confirmed in his principality. Prince Mamia Gurieli, ruler of Guria, was

taken under the Russian aegis in 1811, receiving insignia of investiture from

the Tsar. Only King Solomon II of Imereti held out to the bitter end.

Encircled by Russian troops, the king strenuously resisted

an demands for submission, in spite of the fact that he had earlier, under

pressure, sworn fealty to the Tsar. In 1810, the Russians despatched an

ultimatum to Solomon, demanding that he hand over the heir to his throne and

other Imeretian notables as hostages, and reside permanently under Russian

surveillance in his capital at Kutaisi.

Solomon refused, and was declared to have forfeited his throne. Hounded by

Russian troops and by Georgian princes hostile to him, he sought refuge in

the hills, but was soon captured and escorted to Tbilisi. A few weeks later, Solomon staged

a dramatic escape from Russian custody, and took refuge with the Turkish

pasha at the frontier city of Akhaltsikhe.

Inspired by this daring feat, the people of Imereti rose against the Russian

invaders. Ten fierce engagements were fought between the Russian forces and

the guerillas of Imereti. Famine and plague broke out, and some 30,000 people

perished, while hundreds of peasant families sought refuge in Eastern Georgia. Eventually the patriots were crushed

by armed force. A Russian administration was set up in Kutaisi, the country placed under martial

law.

King Solomon

of Imereti

King Solomon now applied for help to the Shah of Persia,

to the Sultan of Turkey, and to Napoleon Bonaparte himself. To the Emperor of

the French, Solomon wrote in 1811 that the Muscovite Tsar had unjustly and

illegally stripped him of his royal estate, and that it behoved Napoleon, as

supreme head of Christendom, to 'take cognizance of the act of pitiless

brigandage' which the Russians had committed against him. 'May Your Majesty

add to your glorious titles that of Emperor of Asia! But may you deign to

liberate me, together with a million Christian souls, from the yoke of the

pitiless emperor of Moscow, either by your lofty mediation, or else by the

might of your all-powerful arm, and set me beneath the protective shadow of

your guardianship!" 26 Napoleon

himself was, of course, quite a connoisseur of 'pitiless brigandage'.

However, this eloquent plea, which reached him shortly before he set out on

his ill-fated campaign to Moscow, provided him with encouraging evidence of

the unsettled condition of Russia's Transcaucasian provinces. But as things

turned out, Napoleon could not save even his own Grand Army from virtual

annihilation, let alone a princeling down in the distant Caucasus.

Without regaining power, Solomon died in exile in 1815, and was buried in the

cathedral of Saint Gregory of Nyssa in Trebizond.

The elimination of King Solomon did not bring civil strife

in Georgia

to an end. No sooner was Western Georgia

outwardly pacified than fresh troubles broke out in Kartli and Kakheti. Ten

years of Russian occupation had greatly changed the attitude of a people who,

a decade before, had welcomed the Russians as deliverers from the infidel

Persians and Turks. Called upon to furnish transport, fodder and supplies to

the Russian Army at artificially low rates, and regarded by their new masters

as mere serfs, the Georgian peasantry looked back wistfully to the bad old

days. Under the Georgian kings, though invaded and ravaged by Lezghis,

Persians and Turks, their country had at least been their own. Now it was

simply an insignificant province, engulfed in a vast, alien empire, whose

rulers seemed lacking in sympathy for this cultivated, Christian nation which

had voluntarily placed itself under the protection of its northern neighbour.

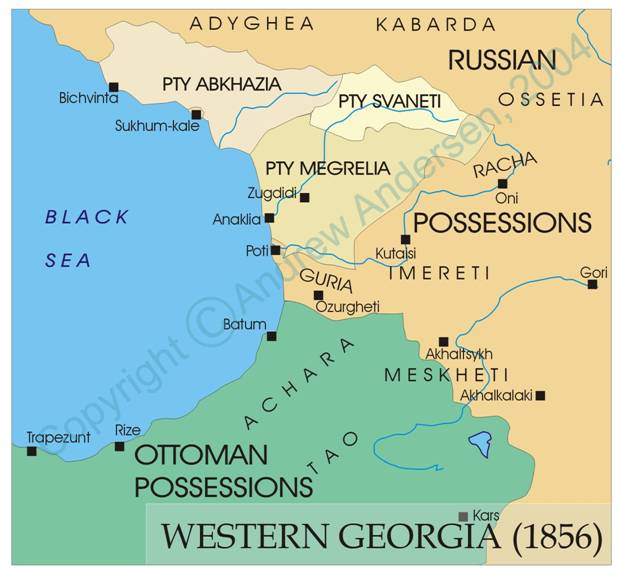

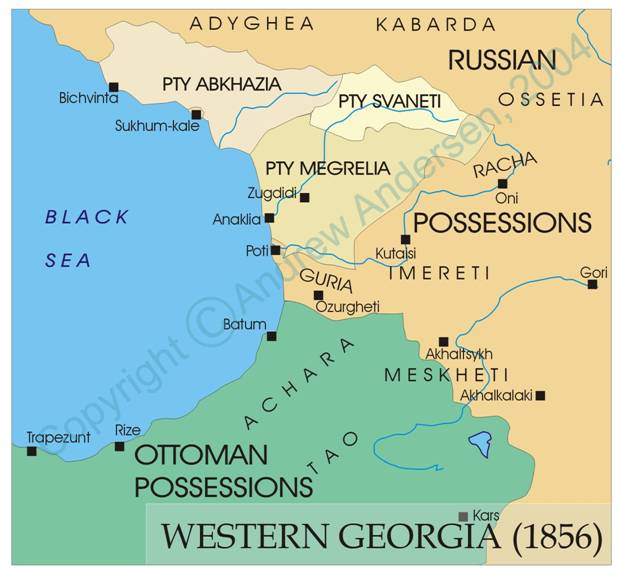

The integration of Western

Georgia

It was at this period that Mingrelia, the Colchis of the ancients, finally lost its autonomy. It

will be recalled that the Dadian or ruling prince of Mingrelia had been

placed under a Russian protectorate in 1803, but had retained a large measure

of authority as a vassal of the cause, and organized a militia to help drive

out the intruders. This invasion imposed a severe strain on the Mingrelian

economy, and particularly on the peasants. When the Turks withdrew, the

landowners attempted to reimpose their authority on their serfs, but were met

with defiance. A peasant revolt broke out, led by a blacksmith named Utu

Mikava. Most of Mingrelia was reduced to a state of turmoil. In the end, both

parties welcomed Russian intervention--the landowners to safeguard their

lives and property, the serfs in the hope of being guaranteed a status

approximating to that enjoyed by crown peasants in Russia. Fate thus played into the

hands of the Russian authorities, who sent in 1857 a commission to Mingrelia,

and removed the Regent Catherine from office. A Russian-dominated Council of

Regency was set up, nominally in the interests of the youthful heir, Nicholas

Dadiani. In 1867, when Nicholas attained his majority, he was compelled to

cede all his sovereign rights to the Tsar in exchange for 1,000,000 rubles, a

grant of estates in Russia,

and the title of Prince Dadian-Mingrelsky. The principality of Mingrelia thus

became an integral part of the Russian empire.

A like fate soon overtook the free mountaineers of Upper

Svaneti, high up in the Caucasus range

looking down over Imereti and Mingrelia. The Russians had long been irked by

the rebellious attitude of the Svanian princes, who spent their ample leisure

in prosecuting blood feuds against one another, and in intrigues with Omar

Pasha's invading Turks. In 1857, Prince Baryatinsky ordered Svaneti to be

subdued by armed force, despite the existence of the treaties of 1833 and

1840, which established a protectorate over the principality of Western Upper

Svaneti and the self-governing tribal area of Free (Eastern Upper) Svaneti.

The ruling prince of Western Upper Svaneti was exiled to Erivan in Armenia.

On his way to banishment, this Svanian prince, Constantine Dadeshkeliani by

name, came to Kutaisi for a farewell audience

with the Governor-General of Western Georgia, Prince Alexander Gagarin, a

jovial man and a good administrator, who had built a boulevard and two

bridges over the Rioni at Kutaisi

and embellished the town with a public garden. At this interview, Constantine

Dadeshkeliani suddenly drew his dagger and stabbed to death the Russian

general and three of his staff.

When captured, he was summarily tried by court martial and

shot. In 1858, the whole of Upper Svaneti was annexed to the Russian

viceroyalty of the Caucasus. Thus ended the

independent existence of this renowned nation of fighters and hunters, mentioned

with respect by Strabo and the ancients, but sunk in more recent times into

squalor and ignorance from which contact with European ways has only lately

begun to redeem them.

The Russians were now able to subjugate Abkhazia, the

autonomous principality situated immediately north-west of Mingrelia along

the Black Sea coastline. It will be recalled

that the Lord of Abkhazia, Safar Bey or Giorgi Sharvashidze, had been

received under Russian protection as long ago as 1809, and confirmed in

perpetual possession of his domains. In the intervening period, Abkhazia had

been frequently involved in the Russian campaigns against the Circassians,

with whom the Abkhaz, many of them Muslims, had cultural, ethnic and

linguistic connexions. During the Crimean War, the Turks stirred up the

Abkhaz against Russia

at the time of null Omar Pasha's invasion of Mingrelia. Turkish envoys who

arrived at the Abkhazian capital, Sukhumi,

found the ruling dynasty of the Sharvashidzes divided: the Christian princes

adhered to the Russian interest, but Iskander (Alexander), a Muslim, was

prepared to help the Turks in return for permission to annex the neighbouring

Mingrelian district of Samurzaqano. Omar Pasha had subsequently landed at Sukhumi, from which he

advanced south-eastwards into Mingrelia. After the Crimean War was over, the

Russians looked for a chance of extending their direct rule to Abkhazia. In

1864, they deposed the ruling prince, Michael Sharvashidze, and annexed his

country by force of arms. Two years later, the Abkhaz staged a general revolt

against their new masters, and recaptured their capital, Sukhumi. The Russians had to send 8,000

troops to quell this rising, which was suppressed with heavy loss of life.

The subjugation of Abkhazia coincided with Russia's

annihilation of the national existence of the Circassians, that valiant North

Caucasian people who had for a century been a thorn in the side of Tsarist

colonialism. Cut off since the Crimean War from contact with Turkey and the Western European powers, the

Circassians were no match for Russia's

military might, especially after the surrender of Shamil and the Murids of

Daghestan. In Chechnya

and Daghestan, the Russians were satisfied with the submission of the local

population to Russian law. But on the Black Sea

coast, their plans involved the seizure of the wide and fertile Cherkess

lands to provide for a part of the wave of Russian peasant migration which

resulted from the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. The Russian government

conceived the drastic project of enforcing the mass migration of the

Circassians to other regions of the empire or, if they preferred, to Ottoman

Turkey. The last shots in the long series of Russo-Circassian conflicts were

fired in 1864. Rather than remain under infidel rule, some 600,000 Circassian

Muslims emigrated to various regions of the Ottoman

Empire, where their descendants may be found to this day. Many

of the Russian, German, Greek and Bulgarian colonists who were endowed with

the tribal lands of the Circassians near the Black Sea

coast proved unable to endure the sub-tropical climate, and the wilderness

invaded the orchards and gardens once cultivated by prosperous and highly

civilized Circassian communities.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

26. French

diplomatic archives, Quai d'Orsay, Paris,

as quoted in M. Lang, The Last Years of the Georgian Monarchy, pp.

263-65.

|

|