|

|

THE STRUGGLE FOR INTERNAL POLITICAL STABILITY AND TERRITORIAL

INTEGRITY, 1918-20

From Károlyi's Baurgeois-Democratic Revolution to Kun's Soviet Republic

The Kádrolyi's government's

last-minute attempt to persuade the Entente Powers to conclude a separate

peace with an independent Hungary and make generous concessions to persuade

the non-Magyar peoples to remain within Hungary failed during the first days

of November 1918. Despite the agreement of the Allies to leave a final

settlement of the new east central European frontiers until after the Paris

Peace Conference the Czechs, Slovaks, Ruthenes, Rumanians, Croats, Serbs and

Slovenes, helped by the French military, now seized those parts of Hungary to

which they laid claim. Ignoring the armistice signed by the commander of the

French Balkan army, Franchet D'Esperey, and the Károlyi government in Belgrade on 7 November 1918, the Rumanian National

Council in Arad

notified the Hungarian authorities on 10 November of the takeover of the

administration in twenty-three counties and parts of three other counties.

Rumanian troops advanced into Transylvania whose annexation was unilaterally

proclaimed by the Bucharest

government on 11 January 1919. The Serbs had already taken over the

administration of the Bácska, the Baranya and the western Banat

on 24 November 1918, presenting the Hungarians with a well-nigh irreversible fait accompli. Czech troops advanced into Slovakia,

or 'Upper Hungary' as it was formerly

called, and were poised to occupy the districts of Ung, Ugosca, Bereg and

Máramaros with their Ruthenian population, to which the Rumanians

also laid claim. On 3 and 23 December 1918, the Allied Supreme Command agreed

to the takeover of the civilian administration by the Czech authorities. On

29 October, the diet of the Kingdom

of Croatia and Slavonia had

announced an end to its ties with Hungary

and the Habsburg monarchy and joined Serbia. In view of the realities

of the situation the Hungarians were unable to take any effective measures to

prevent the break-up of their country.

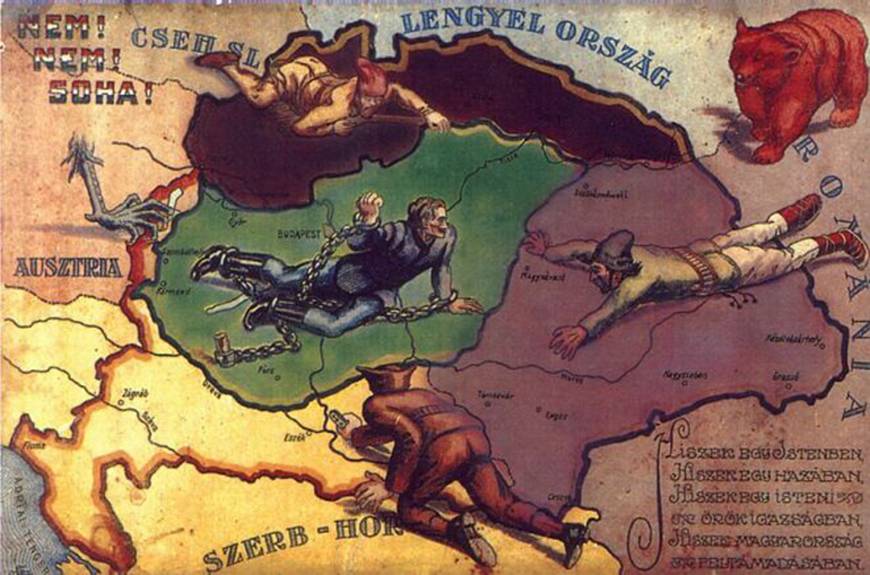

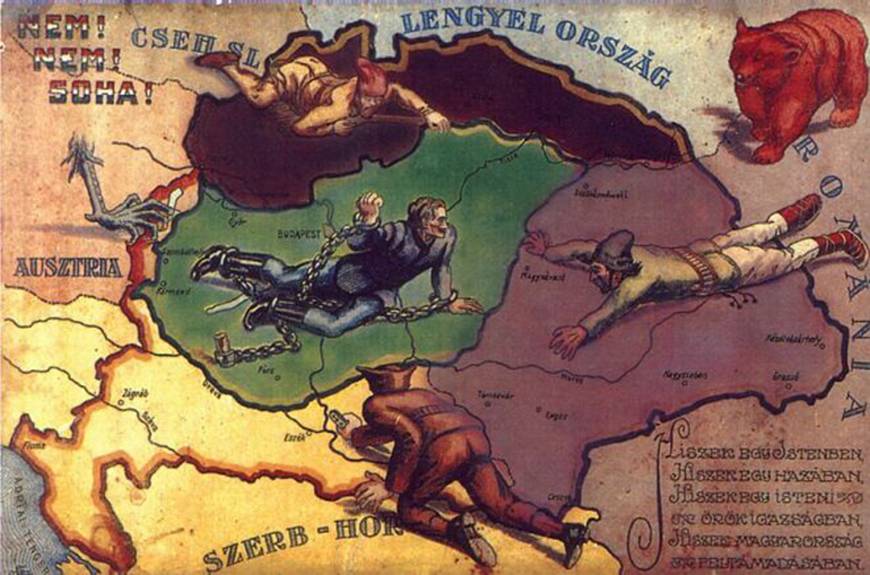

Hungarian poster reflecting

territorial claims of Hungary’s

neighbours after her voluntary disarmament

This dismemberment of the Monarchy, which the

Hungarians were powerless to resist, caused a growing sense of bitterness

among the Hungarian population and increasingly undermined the prime

minister's prestige. Károlyi was regarded as relatively pro-Entente and a

politician who enjoyed good relations with western statesmen. As early as

1914 in the USA and again

in neutral Switzerland in

the autumn of 1917 he had argued for his belief in the need for an

evolutionary change in Hungary's

socio-economic and political conditions. The tough actions taken by the

emerging nation states, tolerated, though not always approved of by the

allied governments, showed that, contrary to expectations, Hungary could not hope for more

considerate treatment. The Károlyi government was particularly disappointed

by the Entente Powers' growing readiness to depart from the principles set

out in Wilson's Fourteen Points, which those

groups willing to introduce reforms had been in the end prepared to use as a

basis for the necessary restructuring of an independent Hungary. The argument that Hungary's

premier, István Tisza, like the Hungarian population in general, had opposed

the unleashing of the First World War in the summer of 1914 failed to

persuade the Allies to grant more favourable peace terms.

With the growing willingness of the Allied

governments to allow a ring of territorially well-endowed successor states to

emerge, confining Hungary to a relatively narrow area of Magyar settlement,

the progressive idea of the new minister for nationalities, Oszkár Jászi, to

make Hungary a kind of 'eastern Switzerland', became untenable. As well as

analysing and condemning former policies towards the nationalities, Jászi

proposed working towards a new form of coexistence between the nations in the

Danube Basin on the basis of extensive political

and cultural autonomy. However, during the course of the discussions with

Slovak and Rumanian representatives it soon became clear that even the most

generous concessions could not overcome their desire to join their

conationals in the new or already existing nation states which had been

greatly enlarged by the acquisition of new territories. The I ncreasingly

obvious impossibility of breaking out of Hungary's foreign policy isolation

and preventing the country's territorial disintegration prior to the terms of

the Paris Peace Conference being made known also increasingly limited

Károlyi's room for manoeuvre in domestic politics.

The first new government measures were

infused with a progressive spirit and met with broad approval. A new

electoral law extended the franchise to all men and the majority of women

over 21 who had been Hungarian citizens for a period of at least six years.

Future elections were to be conducted by secret ballot. In a similar liberal

and generous spirit the government guaranteed by law freedom of the press,

assembly and speech. The Ruthenian population was granted autonomy and

preparations made to introduce a land reform. The workers won the acceptance

of their demand for an eight-hour working day, first raised a decade previously,

although there was still insufficient work available and food shortages. The

effects of the Allied blockade, the disruption to Hungary's

close economic ties with Austria,

together with the military occupation of major territories in the north,

south and east of the country, all contributed to a general situation which

brought factory production to a standstill. Shortages of raw materials and

fuel, together with the disruption to freight traffic, produced maximum

economic chaos. The unemployment figures rose daily. Returning prisoners of

war and demobilised soldiers swelled the flood of refugees from the occupied

territories who were often homeless and incapable of making ends meet. The

country's finances had been completely ruined by the war and could not be

used to alleviate the widespread distress. Appeals for voluntary donations

showed people's willingness to help, but donations of clothes and money were

inadequate to provide effective long-term relief. A feeling of growing

bitterness spread among people facing basic food shortages in the urban

areas, since they suspected landowners and wealthy peasants of deliberately

holding back deliveries to the starving towns. The refusal of many landowners

to cultivate their fields in view of the impending land reform and the

growing impatience of the rural proletariat, which saw no sign of the

promised redistribution of cultivable land, heightened tensions and created

an explosive atmosphere.

Because its proposals for a democratic

reform of society were increasingly criticised and condemned by the political

Right as too radical and partisan, the Károlyi government felt obliged to

take steps to prevent developments taking a more radical direction. The

minister of defence, Bartha, who had been behind the setting up of special

armed units to defend the government and the property of the state, was

forced to resign from his post as a result of public pressure. But the

minister of the interior, Count Tivadar Batthyány, also resigned on the

grounds that the measures taken against the threats from the Left were too

lax. Government officials were very hesitant about pushing through laws which

ran counter to their own political beliefs. Members of the army officer corps

founded secret organisations committed to the defence of the fatherland which

Gyula Gömbös, a general staff captain and future prime minister, tried to

unite in the Hungarian Militia Association.

The political Left was also in the process

of organising itself. A small nucleus of political activists had been formed

from among the half a million or so Hungarian soldiers who had ended up in

Russian captivity and had in many cases been influenced by Marxist-Leninist

ideology. After their release from captivity they had spread the message of

Socialist revolution and had made their mark as organisers and speakers at

mass demonstrations both before and after the revolution of 1918. Some, like

Béla Kun, had also taken an active part in the Russian revolution and had

fought in the ranks of the Red Guard. On his return to Budapest Kun, who

derived great authority from being one of Lenin's former colleagues, had

immediately made contact with the Social Democratic Party's left wing and the

Revolutionary Socialists. The latter had played a major part in the

preparation and execution of the 'Chrysanthemum revolution', but were

dissatisfied with the official line of their parties who were content with a

bourgeois democratic revolution. The Soldiers' and Workers' Councils which

had appeared spontaneously in both the capital and the provinces, had not

grown as dynamically as had been hoped. It was felt that it would be

impossible to implement a political programme or gain a say in government

without first developing a strict party organisation. On 24 November 1918,

therefore, the Communist Party of Hungary (Kommunisták Magyarországi

Pártja) was founded and soon published its own newspaper theVörös

Újság (Red News).

The new party, which at first concentrated

its activities on the big factories in Budapest

and the soldiers garrisoned in the capital, soon tried to whip up support for

its programme in the provinces too. Its aims were varied, Its propaganda

concentrated on crushing the 'counter-revolution', exposing the betrayal

perpetrated by the 'right-wing' leaders of the Social Democratic Party and

creating a system of Soviets on the Bolshevik model. It also put forward

concrete demands for a 'complete break with the remnants of feudalism', an

end to cooperation with the bourgeoisie and its corrupt politicians and a

change in Hungarian foreign policy away from the Entente and towards an

alliance with the new Soviet Russia. Although the nucleus of the Communist

Party remained relatively small in size, Communist slogans had an effective

appeal in a situation of growing social distress and widespread

dissatisfaction. They helped weaken popular support for the Social Democrats

and thus for the government coalition. Revolutionary Soldiers', Workers' and

Peasants' Councils were now also formed in the provincial towns and pursued

policies very close to the Communist Party programme. As early as late

December demonstrators organised by the Communist Party demanded the

proclamation of a Hungarian

Soviet Republic.

The entire country was engulfed by a wave of strikes as infuriated workers

took over their factories and seized transport and communications

installations. When the government sent in the army to restore order numerous

factories were occupied between the 1 and 5 January 1919 and control of

production passed to the Communist-dominated Soviets.

The government turned out to be no match for

this deeply motivated revolt. After lengthy discussions the internal argument

within the Social Democratic Party, whether, in view of the masses' action

and the Communists' growing influence, it would not make more sense to

withdraw from participation in the government in order to retain some of

their influence with the workers, or whether the Social Democrats could

better defend their positions in the crisis by assuming an even more

prominent role in government, was decided in favour of those who supported

continuing the policy of shared governmental responsibility. The party's

National Council hoped that Count Mihály Karolyi's appointment as President

of the Republic on 11 January 1919 and the entrusting of the former minister

of justice, DU +00E9nes Berinkey, with the formation of a new government

would bring about greater stability. The Social Democrats occupied five posts

in the new government, including Vilmos Böhm as minister of defence. The

Smallholders' Party nominated the popular István Nagyatádi Szábo for the new

government as a man who could be expected to speed up the land reform for

which the peasants were becoming more impatient. The Social Democrats tried

to tame the left wing of their own party at first. After an emergency party

conference had approved tough measures on 28 January 1919 the Budapest

Workers' Council expelled the Communists from its membership and that of the

trade unions. Following the dissolution of the spontaneously elected workers'

councils, which had proved impossible to control, workers' participation was

to be guaranteed by elected shop-floor committees in all factories with more

than 25 employees. The Law for the Protection of the Republic gave the

minister of the interior the power to order the internment of persons

considered dangerous to the state. However, it was members of the right-wing

opposition who proved to be the first victims of the preventive measure. The

government undertook a thorough purge of the bureaucracy, dismissing the

lord-lieutenants of the county administrations. The dissolved county

commissions were replaced by elected People's Councils. The Militia

Association was banned and measures carried out against the conservative

elements around the president's older brother, Count józsef Kádrolyi, and

Count István Bethlen, who tried to unite their supporters in the county

administrations in a new right-wing opposition party. By announcing the law

on land reform on 16 February 1919 the government hoped to calm the

revolutionary mood in the countryside. All estates of over 300 hectares were

to be expropriated and compensation paid to their owners. These were then to

be parcelled out with the aim of creating a new economic structure based on

small peasant farms allocated to the small and dwarf-holding peasantry. The

new president, Mihály Károlyi began personally to redistribute the land on

his great estates in Kálkápolna on 23 February.

However, this land reform sparked off a new

internal political conflict. The large-scale landowners showed little

inclination to support the passage of the proposed legislation and offered

stubborn resistance. The rural proletariat reacted bitterly at the

government's completely inadequate upper limit on the size of individual

allocations. They also criticised the lengthy and cumbersome process of

redistribution which prevented the transfer of ownership in time for the

spring planting of crops and complained at the amount of compensation they

were expected to pay, sums which the poor rural population could not in fact

afford. When the government refused to halt the work of the land distribution

committees and satisfy the calls for reform, voiced with increasing

bitterness by the intended beneficiaries, the number of land seizures by the

peasants began to rise from the beginning of March 1919 onwards as attempts

were made to cultivate the land collectively. Even the newly appointed

government officials who were supposed to take over the leading positions in

the county administrations were not always able to take up office and had to

watch helplessly as makeshift committees, dominated by landless peasants and

workers, usurped the administration's functions. In some provincial towns

such as Szeged

the town council was controlled by workers' committees set up by the

left-wing Social Democrats and the Communists.

Even the arrest of the Communist Party's

leaders on 21 February 1919, which the Social Democrats also agreed to after

considerable hesitation, failed to dampen the mood of revolution. The arrests

had come about as a result of a demonstration organised by the Communists

outside the editorial building of the Social Democratic daily newspaper Népszava(The Voice of the

People), where several policemen had been killed the previous day. Since, at

Károlyi's request, the fifty or so defendants were granted the status of

political prisoners, they were also able to lead the Communists from inside

prison and create more difficulties for the government whose image was

completely tarnished, not least because of its lack of success in foreign

policy.

As early as November 1918 the Károlyi

government had tried to establish closer contacts with Italy in the hope of acquiring a

spokesman at the Paris Peace Conference. The government's willingness to

settle the problem of Hungary's

disputed territories and develop economic relations with its neighbours was

communicated to the new South Slav kingdom

of Yugoslavia. In Vienna and Berne, where

the Hungarian diplomats had been accredited without further ado, the opportunity

presented itself of establishing the first direct contacts with the western

Allies and putting the Hungarian case. An economic mission led by A.E.

Taylor, followed by a political mission headed by A.C. Coolidge on 15 January

1919, renewed Hungarian hopes of being included in America's financial aid programme

under the direction of Herbert Hoover. It was clear that the country's

national economic recovery was bound to have an affect on the government's

ability to stabilise the internal political situation. With the Allied

military intervention against Bolshevik Russia fully underway, the Hungarians

felt they could expect an acceptable settlement of the frontier problem from

the Paris Peace Conference, since this appeared to be the only way of avoiding

revolution and a takeover of power by the radical Left in Hungary. Thus, the

measures taken to curb the influence of the Communists also stemmed from

foreign policy considerations.

However, the Peace Conference decision of 26

February 1919, first intimated to the Hungarian government in Budapest on 20 March,

effectively swept the Kádrolyi government from office. It proposed creating a

neutral zone in the south-east of the country in order to separate the

opposing Hungarian and Rumanian forces, which stood ready for battle on the

demarcation line, and envisaged sending in more Allied troops. Acceptance of

these proposals would have exacerbated Hungary's internal political

crisis which had already reached a dangerous level after the Communist Party

announced its intention of liberating its imprisoned leaders by holding a

mass demonstration on 23 March. The Social Democrats, pressed by Károlyi to

take over sole responsibility for the government, intensified their ongoing

negotiations with the imprisoned Communist leaders. In view of the external

political threat faced by Hungary,

the Social Democrats announced their willingness on 21 March to unite with

the Hungarian Communist Party to form the United Workers' Party of Hungary ( Magyarországi Szocialista Párt)

and to form a new government of both parties pledged to implementing

important points in the Communist Party programme. After Károlyi had rejected

the Allies' demands as unacceptable he transferred power 'on behalf of the

proletarian class' to this new government, the Revolutionary Governing

Council ( Forradalmi

Kormányzótanćs). Although its chairman was the Social Democratic

Centralist, Sándor Garbai, it was effectively led by Béla Kun who had secured

his position as head of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs.

On the 22 March 1919, the new government

proclaimed Hungary

a republic and announced its declared aim of establishing the dictatorship of

the proletariat. Proclaiming its desire to live in peace with all peoples, to

maintain relations with the western powers and arrive at a just compromise

with the country's nationalities, it announced that the most important tasks

facing the new Soviet Republic were the construction of a Socialist

society and the forging of an alliance with the Soviet

Union. Kun, who soon claimed and received dictatorial powers,

placed his faith in the prospect of military help from the Red Army to defend

Hungarian territory, interpreted as a struggle against the imperialism of the

capitalist powers. The vast majority of the population was at first persuaded

by this view and prepared to take up arms to defend Hungary's territorial unity,

although most thought little of the Communists' utopian doctrinaire measures

in internal politics. There was no opposition, nor protests, at first, since

only a completely new political departure appeared to offer Hungary the chance to break out

of its foreign policy isolation and take the heat out of the confused

internal political situation. Although the number of organised Communists remained

few, the majority of Social Democrats, many bourgeois radicals and even

reformist liberals supported the change introduced by the new Soviet

government. There followed a rapid succession of decrees which in the course

of time revealed the dominant influence of the Communists.

On 25 March 1919, the government officially

announced a reorganisation of the armed forces and the creation of the

Hungarian Red Army. This was to be recruited from the organised workers with

political commissars attached to each unit in order to counteract the

influence of the old officer corps and ensure that the troops were

successfully re-educated ideologically. The Red Guard, in which Communist

supporters occupied all the key positions, was charged with maintaining

internal law and order instead of the police and the gendarmerie. The courts

were replaced by revolutionary tribunals on which lay-judges, loyal to the

party line, were given the final say. On 26 March, mining and transport were

nationalised along with industrial concerns with more than twenty employees.

These were to be managed in future by production commissars and controlled by

elected workers' councils. Banks, insurance companies and home ownership were

likewise placed under state control. By placing accommodation under public

ownership an attempt was made to overcome the housing shortage caused by the

flood of refugees. Social policy measures -- wage increases, sexual equality,

the prohibition of child labour, improved educational opportunities -- met

with widespread approval, as did the nationalisation of major commercial

concerns, the introduction of food and consumer goods rationing and the

supervised distribution of food by the trade unions. On 29 March 1919, it was

announced that schools and educational institutions were also now the

property of the state. Up to 80 per cent of elementary schools and 65 per

cent of middle-schools had previously been run by the Church. It was

envisaged that members of the Church's teaching orders would continue to be

employed on condition that they were prepared to enter the state service.

György Lukács, People's Commissar for Education, also proposed a progressive

reform of the universities and the entire range of cultural activities, and

began a campaign against illiteracy.

The government's most radical measure was

the land reform decrees of 3 April. Middle and large-sized estates together

with their inventories were expropriated without compensation and taken into

state ownership. The Church's landed properties were also subsequently

nationalised, although some land was spared in order to support the clergy.

The division of land into individual plots was forbidden. Estates were to be

collectively managed by agricultural cooperatives, whereby the previous

owners, tenants and managers had to take charge as 'production commissars',

who would be subject to control by the People's Soviets, comprising former

rural labourers and farmhands, i.e. the so-called 'collective farm workers'.

In the belief that large-scale enterprises would effectively produce more to

cover food requirements than small peasant farms lacking capital, machinery

and seed stocks, the rural poor's spontaneous land seizures, hitherto

encouraged by the Communists, were now reversed. However, dissatisfaction

with this measure was so great in some districts that the government was soon

obliged to allow the creation of small plots or allotments.

In order to acquire political legitimacy and

popular support for their far-reaching measures, which resulted in

considerable social change and unforeseeable changes in the production and

administrative apparatus, Soviet elections were held between 7 and 10 April

on the basis of the extended suffrage granted by the provisional constitution

of 2 April 1919. Since there was only a single list of candidates, the

Revolutionary Governing Council could be sure of winning a majority for its

programme which was increasingly modelled on Soviet-Russian organisational

principles. But in both the Socialist Party and the Revolutionary Governing Council

the former Social Democrats, who harboured growing reservations regarding

Kun's new direction in foreign policy, began to raise objections to the

flagrant violation of existing legal norms and ruthless persecution of both

actual or potential opponents.

To increase pressure on the Hungarian Soviet

government to change its policies or even resign, the Peace Conference, which

perceived the Soviet

Republic as a threat,

had decided on 28 March to maintain its economic blockade of the country. Hungary could, therefore, cultivate diplomatic

and economic contracts only with Austria. Soviet Russia, itself imperilled by

civil war and Allied intervention, had immediately recognised the Hungarian

Soviet régime, but could not provide effective help. On 24 March, Kun had

asked the Peace Conference to help settle the points at issue by sending a

diplomatic mission to Hungary

and entering into direct negotiations with Soviet government. Since America's President Wilson and Britain's prime minister, Lloyd George, interpreted

the radical turn of events in Hungary

as primarily a result of protest against the violation of Hungarian national

interests and excessive French demands, they argued for the acceptance of

Kun's proposal. Afraid that the Hungarian Communist virus might also spread

to Austria and Germany,

they thought it desirable to show a readiness to make some form of

compromise. But Clemenceau's already mooted idea of establishing a cordon sanitaire in east central Europe appeared a better

guarantee for holding feared German revanchist designs in check, while at the

same time preventing the export of the Russian revolution and isolating Hungary

internationally. The decision to withdraw the French interventionist troops

from the Ukraine and the

Crimea and hand over their weapons to the Rumanian army was motivated by the

idea of using Czechoslovakia

and Rumania, as directly

affected neighbours, to exorcise the red spectre in Hungary. After long discussions

the 'Big Four' finally agreed to send General Smuts to Budapest to sound out the Hungarians'

willingness to negotiate. The talks, which began on 4 April, failed to

produce any concrete results, since the Allies insisted on the creation of a

neutral zone, albeit reduced, in south-east Hungary

and Kun failed to have his proposal accepted of holding a conference of the

powers directly involved to settle the problems of the Danube

region.

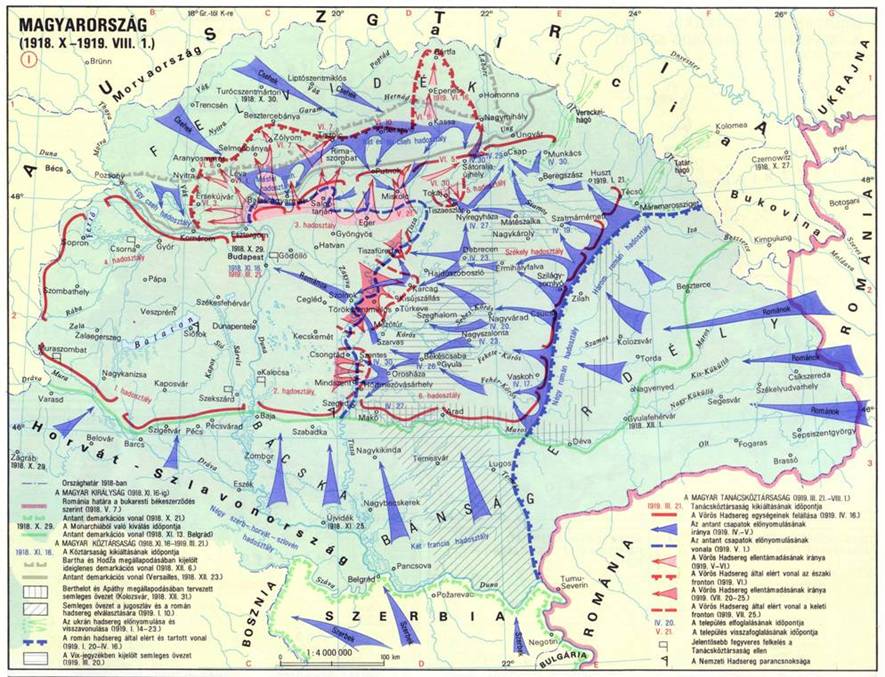

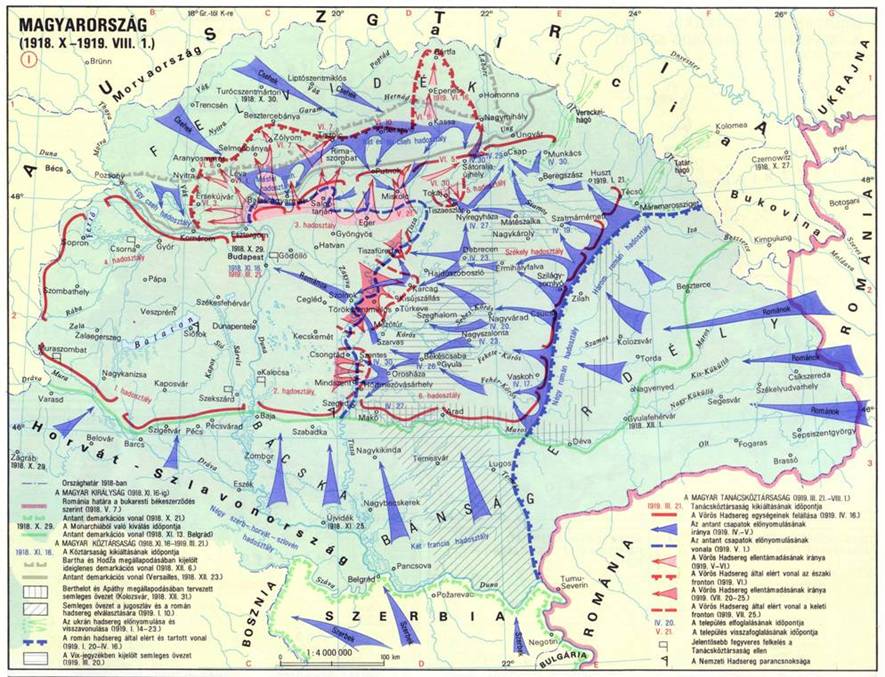

Map from Hungarian Historical Atlas

showing pre-Trianon Hungary, Entente-established demarcation lines, limits of

the territory controlled by Hungarian Soviet government as well as Rumanian

and Czechoslovakian military expansion

of 1918-19.

Click on the map for higher resolution

The Rumanian Crown Council, in a decree of

10 April 1919, decided, therefore, to insist on a military solution of its

territorial claims against Hungary.

Although the newly formed Kingdom of

Serbs, Croats and Slovenes refused

to join in any common action, Czechoslovakia

also made military preparations. At first the Hungarian Red Army failed to

halt the Rumanian advance which began on 16 April, with the result that Hungary had to surrender its territories east

of the river Tisza. Earnest appeals and a

wave of patriotism did, however, result in a rush of volunteers, especially

after Czech units joined the campaign. A Committee of Public Safety,

organised by Tibor Szamuely, increased the pressure on the civilian

population and soon practised open terror against all suspected sympathisers

of the Society for the Liberation of Hungary, founded by Count István Bethlen

in Vienna on

13 April 1919. Against the background of a steadily deteriorating military

situation and the failure of Hungary's increasingly anxious appeals to the

Peace Conference and neighbouring governments, the Social Democratic People's

Commissars showed at an emergency sitting of 1 and 2 May 1919 that they were

prepared to create the conditions to end the military intervention through

the resignation of the Revolutionary Governing Council and the appointment of

a transitional government. With the help of the Budapest Soviet, however, Kun

was able to drum up a majority in favour of continuing the fighting. The Red

Army, which was quickly doubled in strength, began its offensive against the

Czech units in Slovakia

and Ruthenia in the middle of May. Hoping to

create a direct land corridor to Soviet Russia and greatly improve the Soviet Republic's military and political

situation, it managed to achieve a series of quick successes and by the

beginning of June had already succeeded in driving a wedge between the rather

ineffective Czech and Rumanian forces. A short-lived Soviet

Republic was even proclaimed in the

Slovak town of Kassa.

This unexpected recovery by the Hungarians

led to various forms of intensified activity which eventually contributed to

the fall of the Hungarian Soviet régime. In Szeged, which was under the control of

French occupation forces, an anti-Bolshevik Committee was formed in which bourgeois

politicians and members of the bureaucracy, together with some aristocrats

and ex-servicemen, prepared to set up a rival government on 3 June 1919 under

Count Gyula Károlyi's chairmanship. This counter-revolutionary government was

to include Count Pál Teleki as foreign minister and the last

commander-in-chief of the Austro-Hungarian navy and former aide-de-camp to

the Emperor Francis Joseph, Rear Admiral Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya as

minister of war. At the same time, Horthy took over the command of the

National Army which had been mainly organised by Gyula Gömbös.

Dissatisfaction with the Communists expressed itself in revolts in the

countryside and refusals to cooperate. In the towns also, tensions were again

heightened by the crisis caused by basic fuel and food shortages. The

Revolutionary Governing Council tried to blame the peasants for the lack of

food, thus exacerbating the already strained relationship between town and

country, and increasingly resorted to coercion in order to maintain discipline

and keep work going in the unpopular agricultural collectives. A Central

Economic Council was eventually put in charge of the country's entire

economic life with the task of overcoming the supply situation. However, the

discontented rural population increasingly refused to cooperate. Resistance

spread and was merely fuelled further by the government's counter-measures.

In the western counties, in particular, riots and strikes, organised by

ex-army officers and civil servants, flared up repeatedly, especially since

the brutality with which the Red Guard units, charged with the maintenance of

internal order, tried to crush the disturbances, led to a continual increase

in the numbers of those opposing the government.

At the first party congress of the Hungarian

Socialist Party, held on 12-13 June 1919, a head-on clash took place between

groups who opposed the government's handling of domestic and foreign policy.

Many Social Democrats obviously no longer agreed with the partisan direction

of the Communists' policies and sharply condemned the radical measures

against the population. As a result the party changed its name to the

Socialist-Communist Party of Hungarian Workers (Szocialista-Kommunista

Munkások Magyarországi) At the opening session of a new kind of

parliament, the National Congress of Councils (Soviets) which lasted from 14

to 23 June, the Communists succeeded in passing a draft constitution which

was entirely dominated by their ideas. They also demonstrated their

controlling influence on the elections to the Central Executive Committee,

whose task was to control the work of the Revolutionary Governing Council

between the sittings of the National Congress. The deliberations were

interrupted by the news that a major uprising involving the rival Szeged government had broken out between the Danube and

the Tisza. The unrest spilled over to Budapest on 24 June as

ex-servicemen gave their support to the government's opponents. By deploying

Red Guard units, the government once more succeeded in crushing the

disturbances, not least because the industrial workers refused to join the

ranks of insurgents. But, since the workers were also not prepared to

continue supporting the Soviet régime, the position of the Revolutionary

Governing Council became increasingly precarious.

The actions of the Entente Powers also

contributed to the crisis, True, the hastily conceived plan for an Allied

military intervention was soon dropped in favour of diplomatic and economic

pressure, but this made little impression on the Governing Council. The

demand, communicated to the Budapest

government on 7 June 1919, to stop the further advance of the Red Army to the

north-east in order to begin peace negotiations in Paris with the participation of Hungarian

delegates was ignored. On 13 June, an offer arrived from Paris

that if the Hungarian troops retreated to the former demarcation line, the

Rumanian army would be pulled back from the Tisza

to its original positions. In view of the Hungarian army's logistical

problems and growing internal resistance this proposal was accepted, though

with some reservations. The Red Army began to pull back. Many of its generals

and officers, who up until now had fought in order to fulfil their patriotic

duty and defend their country, protested at this climb-down. The

commander-in-chief, Vilmos Bőhm, and the chief of the general staff,

Aurél Stromfeld, joined others in resigning their commissions in protest. It

was also announced on 2 July that the Rumanians were refusing to withdraw

their troops from the line of the Tisza

until the Hungarian army had been completely disarmed.

When Kun wanted to force the evacuation of

the territories beyond the Tisza by

launching a surprise attack on 20 July 1919, the Red Army managed to achieve

some initial victories, but was forced to fall back in disorderly flight when

the Rumanians launched their counter-attack. In the final days of July

Rumanian troops crossed the Tisza along a

broad front. By 31 July, only 100 kilometres separated them from Budapest. Trade

unionists and former Social Democrats had already expressed their view more

openly that the occupation of the entire country by foreign troops could be

prevented only by expelling the Communists from the Governing Council and

forming a new government which the Entente Powers would recognise as a

negotiating partner. This view was reinforced by reports from Vienna where Entente

diplomats had presented the Hungarian negotiator, Vilmos Bőhm, with a

list of eight points setting out their conditions for ending the Rumanian advance

and beginning peace negotiations. The first condition demanded the voluntary

resignation of the Governing Council and the creation of a caretaker

government under the leadership of the trade unions. Although the Communists

still refused to open the way for a negotiated settlement on 31 July, they

had to accept the resignation of the Governing Council which was forced by

the Budapest Central Workers' Council on 1 August 1919. After a period of 133

days Hungary's

experiment in Soviet dictatorship had collapsed. It had ended, not only

because of its total rejection by the Allies and the military superiority of

its enemies, but because of internal opposition which had derived its

strength from the government's errors of political judgement, economic problems

and blind terror. Its leaders fled to Austria where they and their

families were granted political asylum. A transitional government, headed by

Gyula Peidl, had to try to minimise the damage caused to Hungary by Soviet rule.

The 'White Terror' and the Trianon Peace Treaty

In the weeks following the collapse of the

Soviet dictatorship Hungary

faced complete chaos. On 3 August 1919, Rumanian troops marched unopposed

into Budapest

where a succession of helpless and impotent governments rapidly wore themselves

out.

Peidl's 'government of the trade unions',

which was supported only by the Social Democrats, immediately began to repeal

and annul the unpopular decrees and measures of Soviet rule. Private property

was restored, a functioning state apparatus was re-established and what

remained of the 'Red Terror', i.e. the revolutionary tribunals and the Red

Guard, was eliminated. On 6 August, however, Peidl's government was

overthrown in an armed coup. A new government led by the factory owner,

István Friedrich, took over the running of the country. Although the rival

Szeged government aknowledged the authority of the new government, the

former's war minister and commander of the small counter-revolutionary

'National Army', Miklós Horthy, refused to carry out its instructions. Since

the Entente Powers also refused to recognise the new government, its orders

carried no weight and could not put an end to the killing and the looting. In

the meantime, Horthy's troops had advanced into the areas between the Tisza

and the Danube which were not under Rumanian occupation and soon extended

their control over areas west of the Danube

which were now free of foreign military occupation. Real and alleged

Communists were ruthlessly persecuted along with workers and peasants who had

played an active part in implementing the Soviet government's programme. The

same fate was shared by the Jews who suffered considerable loss of life in

punitive actions reminiscent of mediaeval pogroms. The officer detachments

responsible for the 'White Terror' were actively supported by such newly

formed paramilitary organisations as the Hungarian National Defence Force

Association and the Association of Vigilant Hungarians, whose members were

drawn mainly from the ranks of the reserve officers, students, civil servants

and those Magyars who had been socially and economically uprooted following

their expulsion from the former nationality territories now lost to Hungary's

new neighbours. This 'White Terror', which raged throughout the countryside

until the autumn of 1919 and died away only slowly in the spring of 1920,

bore no semblance of legality. It claimed around 5,000 lives, put 70,000

citizens behind bars or crowded them into hastily erected internment camps

and forced many suspects to flee abroad.

A mission of the Entente Powers, which

arrived in Budapest

on 5 August 1919, did little to stop the unbridled persecution and chaos.

Whereas the various Hungarian governments tried in vain to maintain internal

order and political stability, most of the government commissars in the

counties, who were appointed from among the wealthy landowners, had

sufficient power and means at heir disposal to

restore traditional authority and property relations while at the same time

reversing the principles of democratic liberal reform. They were fully

supported by those groups in the towns and countryside who were horrified at

the extent of the Soviet government's democratisation measures and the 'Red

Terror'. These were the aristocracy, civil servants, the military and middle

and small-ranking property owners in the towns who had no sympathy for the

appeals of the intelligentsia -- itself implicated in the failure of

democratic reforms -- not to let Hungary depart from the

principles of parliamentary democracy. The visit of the British diplomat Sir

George Clerk in October 1919 was evidence of the western Allies' interest in

seeing a liberal parliamentary democracy established in Hungary. The Allies also urgently

demanded that a general election, based on the secret ballot, should be held

for a national assembly, conceived as a single chamber parliament elected

bianually. The only reason that the Hungarians reluctantly agreed to these

proposals was that they were the only means by which they could secure the

withdrawal of the Rumanian troops from Budapest.

After 16 November 1919, when Horthy entered the capital at the head of his

National Army, now swollen to 25,000 men, a government of national

concentration led by the Christian Social leader, Károlyi Huszár, was formed

on 25 November. The post of social welfare minister was filled by Károly

Peyer, the leader of the Social Democratic Party, newly reorganised in

August. But the new government was unable to satisfy expectations that it

would bring stability to the woeful political and economic situation. It

could not and would not take vigorous action against the 'White Terror' at

large throughout the country. As a result, the Social Democrats left the

government on 15 January 1920 and decided to boycott the elections due to be held

on 25 January. The other political factions displayed a lack of unity and

instability. Many influential politicians of the pre-war period like Gyula

Andrássy, Albert Apponyi and István Bethlen initially held back from joining

any of the parties, but instead created independent dissenting groups. Newly

created parties like the National Civic Party, the National Liberal Party or

the Democratic Party lacked popular support and primarily represented

business interests and high finance. In contrast, the Christian National

Unity Party (Keresztény Nemzeti Egyesülgs Pdrtja) which was the result

of a merger on 25 October 1919 between the Christian National Party, the

Christian Social Economic Party and several smaller groups, was able to rely

on the support of both the petty bourgeoisie and the wealthy L

andowners who remained loyal to the Habsburgs and supported their

restoration. In the meantime the National Smallholders' Party, led by István

Nagyatádi Szabó, had become an important political factor. After its merger

with the Party of Arable Farmers and Rural Labourers (Országos Kisgazda és

Földmüves Párt), founded by Gyula Dann, it could count on the support of

the majority of the rural population. Despite the continuation of the 'White

Terror' the freest elections in Hungary's history -- free, because they were

mainly conducted by secret ballot -- produced a majority for the

Smallholders' Party which won 40 per cent of the vote and seventy-nine seats,

while the Christian National Union won 35.1 per cent of the vote and

seventy-four seats. Three further splinter groups returned ten deputies to

the new parliament. The workers, however, still had no represention in the

new National Assembly. When, on 15 June 1920, further elections were held in

the territories which had been under foreign occupation, the Smallholders'

Party succeeded in strengthening its leading position even further.

The Smallholders' demand to introduce land

reform legislation in the interests of its supporters and the problem of the

king were the key issues which the new parliament had to address. All the

parties acknowledged that Hungary's 'indivisible and indissoluble' connection

with the Habsburg crown lands had been severed; but all agreed that the

monarchy should continue to exist beyond the 13 November 1918, although the

Crown's prerogatives had been terminated as of that date. A quarrel now broke

out between the 'Legitimists', who, drawn mainly from among the ranks of the

wealthier magnates and the Catholic episcopacy, considered King Charles IV,

who had not yet abdicated, to be the country's legitimate ruler and those who

supported an elective monarchy based on popular support, i.e. the

middle-ranking landowning nobility and leaders of the Calvinist Church who

held that the monarch's claim to the throne had been forfeited and demanded

the nation's right to choose a new king on the basis of free elections. Since

both sides were unable to reach a compromise on the questions of whether King

Charles was still Hungary's rightful ruler or how they should otherwise

determine the succession, the government fell back on an institution of the

late Middle Ages which Lajos Kossuth had revived in 1849: they proposed

appointing a regent for the duration of the interregnum (Law I of 1920). On 1

March 1920, Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya was elected Regent in a parliament

building occupied by the military at the time.

As commander-in-chief of the Szeged National

Army, which had grown to almost 50,000 men in Transdanubia after joining up

with Baron Antal Lehár's units at the beginning of 1920, Horthy, who was not

a particularly talented military commander or politician, exhibited an

exceptional desire to legitimise his authority. Thanks to his sincere manner

in dealing with others, his ability in several languages and the troops under

his command, he was able to win the support of the Entente representatives

stationed in Budapest.

His active tolerance of the 'White Terror' had made him acceptable to the

enemies of reform as well as those opposed to revolution. They hoped they

could install this reputedly malleable and arrogant professional soldier as a

figurehead to help them achieve their own aims. Horthy knew how to give both

the legitimists and those who supported an elective monarchy the impression

that he supported their respective positions. He also cultivated the image of

a leader who, on account of his good personal contacts with leading Entente

politicians, could obtain improved peace terms for Hungary. But as soon as he was

made Regent, Horthy increasingly pursued his own policy, primarily in the

interests of his own family. The result was that the suspicion soon grew that

he had his eyes on the crown for himself or his eldest son.

On 10 March 1920, the Huszár government made

way for a new cabinet led by Sándor Simonyi-Semadam, whose priority was to

seek an improvement in the harsh peace terms. On 25 November 1919, the

Hungarian government had been invited to send a delegation to Paris to receive the

terms. This delegation, headed by Apponyi, Bethlen and Pál Teleki tried to

have the draft of the peace treaty, which was handed to them on 20 January

1920, changed to more favourable terms on the basis of historical, economic

and legal arguments. They not only pointed to the geographical unity of the

Danube basin up to the natural frontier of the Carpathians in the north and

east and to the fact that the territories recently seized by Czechoslovakia

and Rumania had for a thousand years, since the beginning of the 11th

century, constantly formed part of the crown lands of St Stephen. They also

argued that, despite the intermingling of populations of different

nationalities it would be difficult, though not impossible, to draw a more

equitable frontier. They failed, however, to gain any concessions with their

arguments. The Hungarian government also tried in vain to prevent the

inclusion of a war-guilt clause by pointing out that the Hungarian population

and the prime minister, Tisza, had been opposed to war in the summer of 1914

and suggested changing the proposed terms stipulating a reduction in the size

of armed forces to allow a system of conscription for a standing army of

100,000 men in place of the permitted strength of 35,000. When this also was

rejected, broad sections of the Hungarian population were already bitterly

opposed to the proposed peace treaty even before it was signed in the Trianon

on 4 June 1920, believing that a major revision of its terms was inevitable.

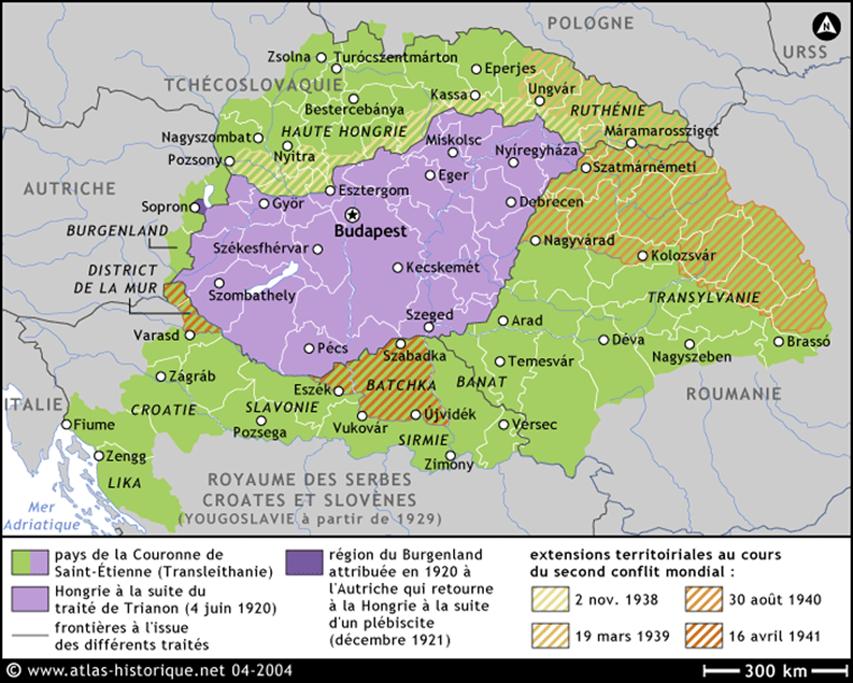

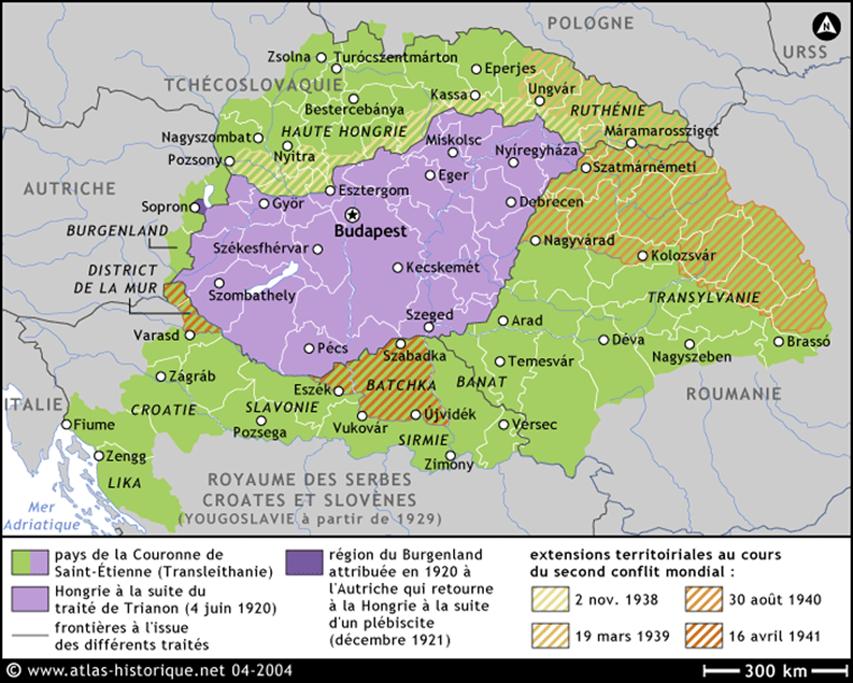

The independent 'Kingdom

of Hungary', which emerged as a

result of the Trianon peace treaty comprised only 92,963 square kilometres

compared with the original 325,411 square kilometres of the old pre-war Kingdom of Hungary. According to the 1920 census,

its population now numbered 7.62 million inhabitants compared with the

earlier figure of 20.9 million. Under the terms of the Treaty the new Kingdom

of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later named Yugloslavia, received the Bácska,

the Baranya and the western Banat, amounting to 20,956 square kilometres,

i.e. 6.44 per cent of pre-war Hungary,

involving the loss of 1.5 million inhabitants. Hungary was obliged to cede

102,787 square kilometres, i.e. 31.59 per cent of its entire territory and

5,265,000 inhabitants to Rumania, the latter obtaining the whole of

Transylvania including the Szekler region, the eastern Banat, most of the

counties of Körös and Tisza and the southern part of Máramaros. Of the 62,937

square kilometres or 19.34 per cent of pre-war Hungary

ceded to the new Czechoslovakian Republic, Slovakia

received 48,994 square kilometres, Ruthenia

12,639. Of the 3,250,000 inhabitants affected by these changes, 2,950,000

were settled in Slovakia

and 571,000 in Ruthenia. More than three

million Magyars now lived under foreign rule: 1,063,000 in Czechoslovakia, 1,700,000 in Rumania and 558,000 in Yugoslavia.

Thanks to Italy's

support, Hungary was at

least able to push part of its claim through against the weak Austrian

government on the question of the Burgenland when a somewhat dubious

plebiscite held on 14 December 1921 resulted in the return to Hungary of the area around Sopron.

Although no exact figure was set, Hungary

had to agree to pay reparations. The armed forces permitted under the treaty,

comprising a professional army of 35,000 men on a long period of service, but

minus heavy artillery, armoured corps and an air force, was intended

exclusively to maintain internal order and the defence of Hungary's frontiers. An

Inter-Allied Control Commission was given the task of seeing that these

armament limitations were observed.

Every section of the Hungarian population

felt disappointment at the scale of losses demanded by the peace treaty,

which came to be regarded as a dictated settlement. The historic Kingdom of Hungary

had possessed a geographical unity without parallel in the rest of Europe. In the second half of the nineteenth century

the national economy had been a coordinated whole in which the different

parts of the country had been mutually dependent on each other and the

capital, Budapest.

This economic unit had been destroyed by the territorial terms of the peace.

The effects of the world economic crisis in 1931-32 made the problems

resulting from the destruction of the Habsburg Empire's unified economy very

apparent and these proved impossible to overcome satisfactorily in the period

before 1938. As a semi-industrialised country with an inadequately developed

manufacturing industry Trianon Hungary began to fall behind

other countries economically. Since its bauxite and oil resources were yet to

be exploited, the government had to give priority to agricultural production.

The war and the period of Soviet rule had done little to reduce the social

tensions which resulted from the partisan redistribution of landed property,

and these played a crucial part in determining the direction taken by Hungary's

domestic and foreign policies during the inter-war period. The influx of

350,000 immigrants from the territories of the successor states, comprising

mainly civil servants, teachers and soldiers, also added to the problem of

achieving social cohesion, since they represented a politically aware group

which could not be so quickly and easily accommodated in a country that had

been reduced so much in size. The only problem solved by the imposition of

the Trianon peace treaty terms was that of the national minorities. According

to the 1920 census, only 833,475 people, i.e. 10.4 per cent of the

population, including 552,000 Germans (6.9 per cent) and 142,000 Slovaks (1.8

per cent), did not speak Hungarian as their mother tongue. According to the

same census, the number of Jews living in Hungary was 473,000.

Despite the sacrifices imposed by the

treaty, Hungary's

government and people continued to identify their dismembered state firmly

with pre-war Hungary.

Deliberately shunning any compromise with the new circumstances, they

remained absolutely inflexible, rejecting even the possibility of any

constructive developments within the new frontiers. They carefully nurtured

the Magyars' sense of an historically based national identity, looking back

to the founding of the state, the Hungarian

Kingdom's thousand

years of history and their belief in the Magyar cultural mission of spreading

their superior civilisation. They kept alive the sense of humiliation at Hungary's

defeat, the experience of economic privation and despair at the injustices of

the peace settlement. In an eruption of national patriotism which permeated

all social classes they argued for a revision of the peace treaty, invoking

the symbol of the crown of St Stephen to argue for the restoration of the territories

lost to their despised neighbours. Although differences of opinion soon

emerged regarding the extent of the desired revision, the treaty's failings

were pilloried. Its unrealistically high reparations demands, war-guilt

clause, territorial and military terms and unjust treatment of the Magyar

minorities in Hungary's

neighbour states all became a focus of resentment. The slogan, 'Nem, nem,

soha!' (no, no, never!) summed up the attitude of every Magyar to the

peace treaty. Diplomatic, artistic and economic contracts with other

countries were cultivated with renewed intensity with a view to revising the

treaty's terms eventually. 'The world's conscience' was not to be allowed to

rest 'in view of the injustices done to Hungary at the Trianon and the

consequent danger to peace'. Whereas at first demands were made to restore to

Hungary its pre-war territories, implying a total revision of the treaty,

which could not be achieved peacefully but only by a victorious war, from

1930 onwards more enlightened circles worked for a revision of the treaty's

territorial terms within the framework of national self-determination: '

Hungary will recover those citizens seized from her whose first language is

Magyar, although plebiscites will be held in territories whose inhabitants'

native language is not Hungarian'.

Hungary's revisionist policy was,

however, primarily intended to divert attention away from the country's

internal social and economic problems. The traditional upper classes, the

aristocratic representatives of the governments and parties of the period

before the Soviet republic, which quickly regained their prominence, were

interested only in preserving what remained of feudal rule, in resisting any

genuine land reform and in obtaining compensation for their extensive

holdings which now lay in the territories seized from Hungary. It

was thanks to their influence that a subtle combination of democratic

elements was incorporated into the new constitution of 28 February 1920 which

did much to perpetuate social injustices. The traditional middle class,

recruited mainly from members of declining middle nobility, who had been

gentrified and earned their living as civil servants or professional

soldiers, tried increasingly to curb the influence of the upper nobility and

secure their politicial and economic position. They were able – especially I n their unbridled campaign

against the Jews -- to count on the complete support of a petty bourgeoisie

which was also imbued with the conviction that it was ordained to rule politically

and economically. Despite a large influx of Jewish immigration before the

First World War, Hungary's

Jews, in fact, formed only 6 per cent of the country's population, but

controlled major areas of industry, banking and commerce as well as dominating

several liberal professions like medicine, the law and journalism. Although

the Jews had not posed a threat to any social class and had created many

positions for the first time in their role as a substitute bourgeoisie, they

were used as a scapegoat in order to release the pent-up dissatisfaction of

the middle classes. Even in the officer corps, which was initially the only

stabilising factor in the state and which exerted considerable influence on

Horthy during his period as Regent, a groundswell of antisemitism combined

with anti-liberal ideals. Above all, it was Hungary's professional soldiers

who rejected democratic institutions and a liberal state based on the rule of

law. Their growing chauvinism and demands for a complete revision of the

peace treaty were accompanied by the call to establish naked authoritarian

rule in the form of an overt military dictatorship. Hungary's governments and

political parties had to resist these tendencies before they could even begin

the long overdue process of consolidation.

|

|