|

|

CHAPTER TWO

Hungary

under the Dual Monarchy, 1867-1918

THE POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND INTELLECTUAL BACKGROUND

The development of the political

parties

Following the long period

of crisis, which originated in the pre- 1848 period, the Compromise of 1867

marked the beginning of almost half a century of peaceful development for the

Dual Monarchy. Many were later to look back on it in a romantic and nostalgic

light as 'the age of Francis Joseph'. Although the new political system

required a period of consolidation, Hungary suddenly experienced an

economic upturn and a sustained period of cultural progress. Though

fundamentally a backward east-central European agrarian country, by virtue of

its belonging to the Habsburg monarchy, Hungary enjoyed particularly

favourable preconditions for modernisation in all areas. This development

affected the country's economic structure much more that its social and

political order which the landowning aristocracy and gentry continued to

dominate. Although Hungary's negotiated autonomy of 1867 was not, of course,

without its limitations, the Compromise restricted Hungary's internal

administration only indirectly, to the extent that any state's domestic

policy is influenced by the international situation at any given moment and

the diplomatic and military measures which inevitably result from this. The

principle of legal and constitutional sovereignty, which had figured

prominently in Law XII of 1867, also included the autonomy of the Hungarian

government in internal affairs, something Andrássy's new government was soon

to make extensive use of. After Deák refused post in the new government Andrássy, a former

revolutionary who had been hanged in effigy in 1848, formed a cabinet

consisting of members of the propertied nobility and the haute bourgeoisie.'

The liberal minister for education and religion, Baron Jozsef Eötvös (d.

1871), a progressive writer, was the most prominent figure in the new cabinet.

the difficult post of finance minister was filled by Count Menyhért Lónyay,

that of minister of justice by Boldizsár Horvát. The new government relied on

a bare two-thirds parliamentary majority of around 250 votes out of a total

of 409 deputies. These were liberals who were held together on the strength

of Deák's personal prestige (and thus often referred to as the Deák Party -Deákpárt),

ranging from Old Conservatives to former advocates of a liberal centralism.

Their newspapers, like the Pesti

Napló, the Budapesti Közlöny and

especially the Pester Lloyd,

were held in high esteem.

These supporters of the 1867 Compromise were

initially opposed by Kálmán Tizsa's Left Centre Party (Balközép),

which numbered about 100 deputies. The landowning nobility of the

middle-sized and smaller estates and the aristocratic intelligentsia were its

chief supporters. Its deputies, most of whom were similarly drawn from the

middle ranks of the nobility, approved of the Compromise as such, but

objected to its form and what they believed were its over-generous

concessions on the question of common affairs. Politically, they aimed at

obtaining a 'more favourable' compromise and regaining their former position

of having the decisive say in government over Hungary's wealthiest landowning

families. They accused the latter of betraying the 1848 Revolution's most

important achievements for the sake of holding on to their own position of

political and economic power. On 2 April 1868, the Left Centre published its

new party programme. "'The Bihar Points'" (Bihari pontok),

which not only called for political independence and the abolition of the

common delegations, but opposed the popular movement beginning to emerge in

the Lower Danube region. The demand that

there should be no change in the existing social order and the declared aim

of pursuing a constitutional reform of the Compromise was bound to appeal

equally to the lesser gentry and middle classes, both of which were hostile

to the government. These political goals, which had popular appeal and were

pursued with nationalist slogans, enabled the Left Centre to win several

seats in the 1869 parliamentary elections from a government party weakened by

internal factions and policy disagreements. In all, a total of 110 Left Centre

deputies were returned to the new parliament which met on 20 April 1869.

Disgusted by opportunism, attempts at

personal enrichment, the strong drift to conservatism and internal party

squabbles, Deák retired from politics. After Eötvös's death, and since Andrássy

was no longer a possible candidate for prime minister after his appointment

as common minister of foreign affairs on 14 November 1871, the office of

Hungarian premier fell to the common finance minister, Count Menyhért Lónyay.

His acute business acumen and close contacts with the conservative

aristocracy meant that he failed to command much respect. He was able to

remain in power only by resorting to brutal measures against the

nationalities and arbitrary actions in internal politics. Opposition to him

grew rapidly, especially when, on the approach of the 1872 elections, he

proposed to narrow the franchise based on the curia system, which, in any

case, benefited only 7.1 per cent of the population and advocated extending

the life of parliament to five years. The elections, which were as usual

rigged and characterised by administrative corruption, resulted in the

government winning 245 seats. However, the premier, accused of corruption,

was no longer able to hold on to office and was forced to resign on 30

November 1873.

The subsequent succession of short-lived

transitional governments failed to prevent the collapse of the government

party or restore the state finances after the disastrous effects of the 1873

economic crisis. The threat of national bankruptcy was avoided only by the

government's acceptance of a loan of 150 million guilders on extremely

unfavourable terms from a foreign consortium of bankers headed by the

Rothschilds. The government and its supporters, already weakened by the

thankless task of having to defend the increasingly unpopular compromise

against exaggerated Magyar nationalist feelings, continued to lose respect as

many firms went into liquidation and the prospect of paying off the impending

financial deficit and of effecting a revival of the economy was slight. To

avoid complete disintegration and at the same time hold on to its share of

power, the government party entered into negotiations with the Left Centre

with a view to merging the two parties. After its poor showing in the 1872

elections, the latter was more willing to compromise and had no wish to let

slip the opportunity of coming to power by legal means. Kálmán Tisza, who

remained uncompromising on questions of social policy and the treatment of Hungary's

nationalities, particularly rejected the idea of organising a broadly based

mass opposition movement in order to help bring his party to power on the

grounds that this more radical course involved too many risks. Following the

enactment of a new electoral law based on existing census returns (law XXXIII

of 1874) on the 1 March 1875, Tisza thought the moment had come to drop the

'Bihar Points' and merge the majority of his Left Centre with the fragmented

and unstable government party. Relying on this new Liberal Party (Szabadelvü

Párt), supported by the landed nobility and the still relatively

insignificant middle class, he was appointed Hungarian prime minister on 20

October 1875 - an office which he held until the 13 March 1890.

This merger led to a significant strengthening

of the pro- 1867 Compromise element in Hungary and was to guarantee the

Liberal Party a monopoly of power for the next thirty years. The other rival

parties found their scope for effective action seriously curtailed. The

social classes which formed the main pillars of the state and which rejected

any moves towards greater democracy were ready to give their full support to

this single party of government, so long as it opposed radical social reform

of any kind and supported, at least in its rhetoric, an improvement in

Hungary's constitutional position within the framework of the Dual Monarchy.

The introduction of a parliamentary system along the lines of the western

European model, involving a regular change of party political direction in

the exercise of governmental responsibility, was thus effectively ruled out.

The weakness of the opposition contributed

to this development. At the outset those who were completely dissatisfied

with the Compromise were represented by only twenty deputies, including those

of the extreme Left, and were, moreover, divided into several factions. They

included Kossuth's radical supporters, who, as loyal defenders of the

achievements of the 1848 Revolution, devoted their energies to restoring the

'undiminished constitution' and establishing a greater measure of democracy

in public affairs through the National Army Associations, founded in 1861. As

a result of a violation of the press censorship law of 1868, their spokesman,

László Böszörményi, was imprisoned by the government and died soon after. The

popular movement led by the lawyer, János 'Asztalos, which demanded a fairer

distribution of land and greater rights of political participation for the

lower classes, was brutally crushed in March 1868 and Asztalos arrested.

Despite its many repressive measures, the government's bureaucratic and legal

attempts failed to prevent the rise of this '1848 party', which József

Madarász formed into a parliamentary opposition on 2 April 1868 (Közjogi

Ellenzék). It managed to win 40 seats at the 1869 elections and added a

further 36 seats in the 1872 elections. Although prepared to acknowledge in

principle a personal union under a common monarch, the '48ers advocated

complete Hungarian independence based on democratic principles, full civil rights

and a progressive franchise. They did not, however, take up the peasants'

demands for a radical land reform, but instead supported only the realisation

of the main points contained in the Liberals' agrarian programme of 1848. In

the spirit of Kossuth, they were prepared to make concessions to the

nationalities. A further reorganisation and, shortly thereafter, a change of

name to the Independence Party (Függetlenségi Párt) can be attributed

to the influence of Kossuth, who was seen as the party's spiritual mentor.

The party programme, which was confidently addressed to the 'Citizens of

Hungary!', held firmly to a position of fundamental opposition to the

Compromise. However, party defections and an increase in the Liberal Party's

membership, saw the political importance of the Independence Party decline

towards the end of the 1870s. Only after incorporating several breakaway

groups in 1884 could the opposition, now renamed the Independence and 48 Party (Függetlenségi

és 48-as Párt), count on the support of nationalist landowners

dissatisfied with government policy, some members of the intelligentsia and

the urban population and wealthier peasants. Closely following the programme

of 1848, the party demanded Hungarian independence, a loose personal union with

the Austrian half of the Empire and middle-class liberal reforms. But endemic

internal disagreements and personal intrigues prevented the party from

realising its political programme and damaged its public image. Nevertheless,

the Independence Party deputies could feel that their aims were endorsed by

the Linz programme of the German National

movement in Austria led by

Georg Ritter von Schönerer which on 1 September 1882 demanded a purely

personal union with Hungary

and called on the latter to annex Bosnia-Herzegovina and Dalmatia.

The right-wing conservative opposition,

holding tenaciously to the legacy of feudalism and supported by the magnates

and court aristocracy, were badly affected by premier Tisza's

policies, even though these were generally hostile to progress. Their United

Opposition Party (Egyesült Ellenzék), founded on 12 April 1878, and

renamed the Moderate Opposition three years later, lacked a programme of

clearly defined aims under Count Albert Apponyi. It favoured strengthening

the idea of a Hungarian state and constitutional power, defended the

Compromise of 1867 and employed anti-liberal slogans which advocated

conservative reforms. But it failed to win significant support in Hungary, its

parliamentary strength falling from 105 deputies originally to only 46 in

1887.

Hungary's political parties

were not at first organised on the basis of ideological positions or social

class loyalties. Their opposition to each other did not result from differing

social programmes, but differing constitutional views and aims. It was only

the unresolved social and political issues resulting from the country's

transition to a bourgeois industrial society -- and growing potentially more

explosive towards the end of the nineteenth century -- that introduced change

to the traditional structure of Hungarian political life and gave rise to

ideologically based parties pursuing social and democratic reforms. But the

new political tendencies expressed in political Catholicism, Socialist

workers' parties, agrarian Socialist associations and also much later by the

organised political representation of the urban intelligentsia, failed to

change political issues and behaviour fundamentally, or effect even modest

democratic and social reforms.

Although a General Workers' Association was

founded on 9 February 1869, there was still no successful attempts at

organising the steadily growing working class. The government acted firmly

against its organisers and, following a wave of strikes in the spring of

1871, had the ringleaders sentenced on 1 May 1872 in the first political

trial against the workers' movement. New attempts to create a single Workers'

Party for the whole of Austria-Hungary,

undertaken with the support of the Austrian labour movement, received fresh

impetus with the adoption of a programme in Neudörfl in April 1874. Sickness

benefit fund associations and the newspaper Népszava (Voice of the People) provided Leo

Frankel, an erstwhile minister in the Paris Commune who had returned to Hungary, with

the opportunity of furthering the establishment of a new party. The

Non-Voters' Party, founded on 21 and 22 April 1878, later to become the

General Workers' Party of Hungary (Magyarországi Általános Munkáspárt)

on 16-17 May 1880, based its programme on Marxist ideology. Demands for a

ten-hour working day, a ban on child labour and a guarantee of equal wages

for women were accompanied by support for basic civil rights and the need for

state control of the means of production. This resurgence of the labour

movement, viewed with mounting mistrust by Tisza's

government, suffered a serious setback with the arrest and imprisonment of

Frankel in 1881, especially since after serving his sentence he went abroad

as a result of constant police surveillance and internal party squabbles. Thus

it was not until the founding of the Hungarian Social Democratic party ( Magyarországi Szociáldemokrata

Párt) in December 1890 that the labour movement found a permanent

organisational structure and effective representation.

Hungary's electoral laws, which were

tightened up on several occasions, excluded the industrial workers, peasant

farmers, domestic servants and urban lower classes from actively

participating in the country's constitutional parliamentary system. Only 6

per cent of the population, i.e. 800,000 people, were entitled to vote. Like

the gerrymandering which was necessary to protect the government's interests,

the electoral laws had a built-in property qualification which ensured that

the discontented, though enfranchised, peasants, middle classes and

nationalities entitled to vote were practically unrepresented in parliament.

Following numerous changes in the number and size of constituencies the Lower

House eventually had 453 members of whom 40 were delegates from the Croation

diet. Up to the late 1870s, 80 per cent of Hungary's parliamentary deputies

were drawn from the landed aristocracy and gentry. In 1910, the figure still

stood at 50 per cent. The number of deputies of middle-class origin - civil

servants, lawyers and intellectuals - never exceeded a third of the total.

Parliamentary deputies of peasant origin were rare. The workers, on the other

hand, had no representation at all. The 1885 reform (Law VII of 1885), which

abolished hereditary seats in cases where the member's land tax amounted to

less than 3,000 guilders per annum, resulted in a fundamental change in the

composition of the Upper House, although the greater nobility continued to

occupy three-quarters of the seats. In addition, the monarch had the right to

appoint as life peers to the Upper House fifty persons of merit nominated by

the Hungarian cabinet. These appointees had a seat and voice in the Upper

House alongside holders of high ecclesiastical offices, a few elevated

representatives of the bureaucracy and the judiciary as well as the

wealthiest landowners, who had held on to their great wealth. The

government's rigging of elections and commissions charged with drawing up the

electoral roll, together with bribery, the falsification of votes,

intimidation of voters and the open ballot were normal practice and ensured

the government a majority in the Lower House of the new parliament. The

corruption which had also spread through the bureaucracy and judiciary helped

the ruling élites not only to defend but to further their position of social

and political predominance. Tisza's skilful use of patronage involving government posts,

commission appointments and honours, helped him to create within his party

and in the inflated but ineffective government apparatus a body of organised

supporters on whose gratitude and loyalty he was able to build.

Magyar nationalism and the failure of

the nationalities policy

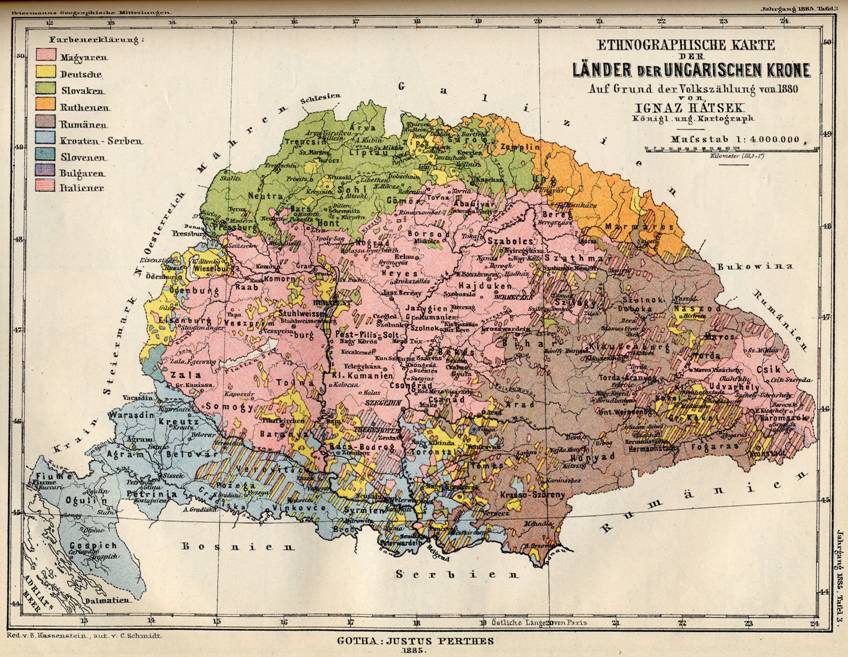

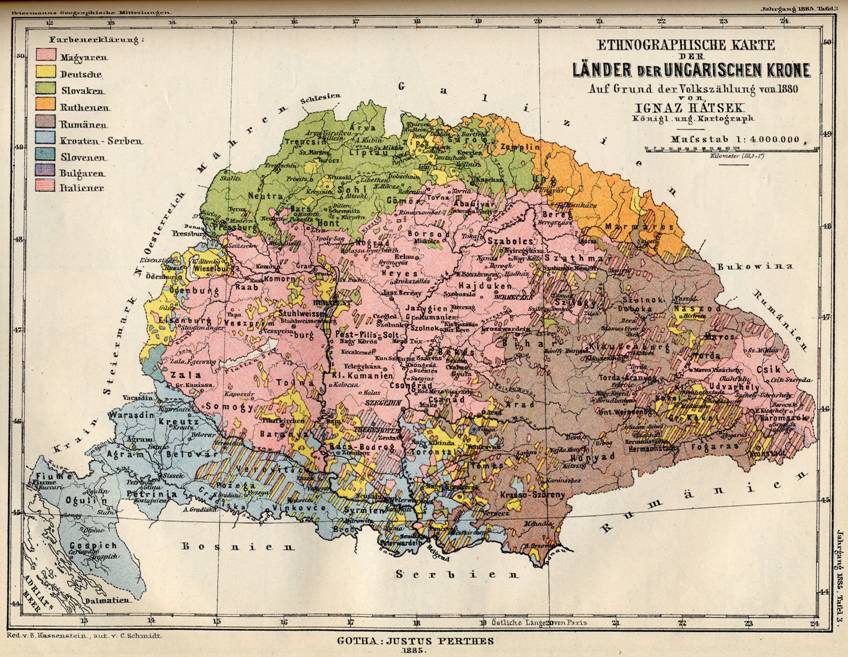

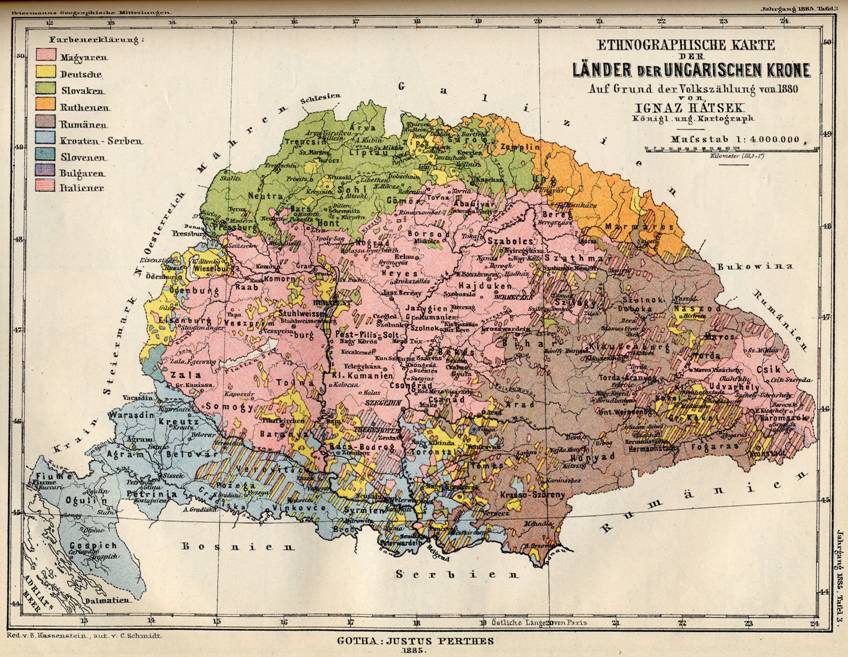

In 1867, following the renewal of the union

with Transylvania and the abolition of the

special 'military frontier' areas, the territorial integrity and political

unity of the historic 'territories of the Holy Crown of Hungary' was

restored. Some 15.5 million people inhabited a total area of 325,411 square

kilometres. Approximately 40 per cent of the total population were Hungarians,

9.8 per cent were Germans, 9.4 per cent Slovaks, 14 per cent Rumanians, 14

per cent South Slavs and 2.3 per cent Ruthenes (Carpatho-Russians and

Carpatho-Ukrainians). One of the first tasks facing the new independent

Hungarian government was to find a speedy settlement of the future

constitutional position of the nationalities, a problem which demanded an

immediate solution. The Emperor Francis Joseph had already stressed the need

for a just settlement of this problem during the negotiations which had led

to the 1867 Compromise and had received Deák's assurance of his desire to

tackle the problem. But after initial contacts were established with the

spokesmen of the non-Magyar nationalities and during the so-called

'mini-Compromise' negotiations with the Croats, the Hungarian 'view that 'in

accordance with the fundamental principles of the constitution, all Hungarian

citizens [constitute] a nation in the political sense, the one and

indivisible Hungarian nation, in which every citizen of the fatherland is a

member who enjoys equal rights, regardless of the national group to which he

belongs' (Law XLIV of 1868) proved to be an insuperable obstacle to any

agreement which would do justice to the needs and expectations of both

parties. Right up to the Habsburg monarchy's dissolution the uncompromisingly

defended fiction of a Magyar nation state on the western European model led

to a denial of the political existence of the non-Magyar nationalities. This

short-sighted attitude prevented any transfer of rights of self-government to

the nationalities which constituted the majority of the population before

1890.

Negotiations were based on the Nationalities

Law which had been passed during the state of emergency in Szeged in 1849. Despite the earlier

promises by the Hungarian Liberals during the negotiations in 1868 on the

matter of 'equality of the nationalities', only Hungarian citizens 'of a

separate mother tongue' were formally recognised and nominally accorded equal

civic rights, the unrestricted use of their native language in the lower

levels of the administration, the judicial system, and elementary and

secondary schools. Only the neighbouring territory of Croatia-Slavonia,

designated as 'a neighbouring territory of the Crown of St Stephen', received

in a 'mini-Compromise' a measure of autonomy in the bureaucracy, the judicial

system, culture and education, which was exercised by provincial governors

who were controlled by the Croation diet. All other areas of activity were

regarded as 'common affairs' and subject to control by the government in Budapest, enlarged to

include a minister without portfolio for Croatian affairs. Forty of the

deputies delegated from the Croatian diet were to ensure the defence of

Croatian interests in the Hungarian parliament. These blinkered arrangements

destroyed the attempts of Deák, Eötvös and even Kossuth to institute a more

sympathetic nationalities policy in a Hungary, whose strongly nationalist

principles could only be implemented ultimately by force on account of the

open opposition of the country's non-Magyars.

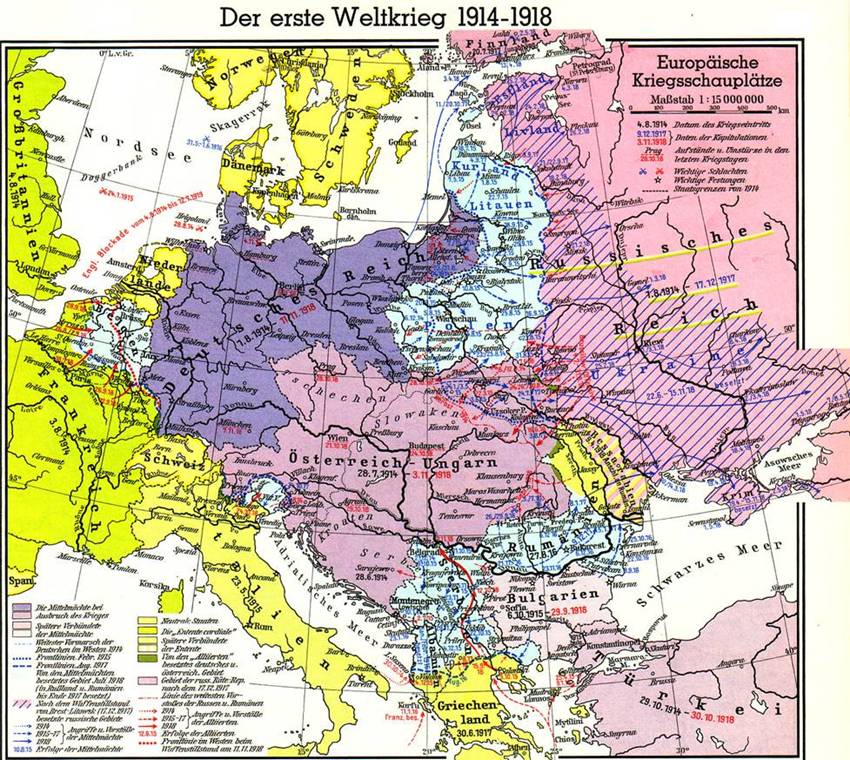

Click on the map for better

resolution

Despite Deák's warning to avoid an abuse of

state power for the sake of Magyar nationalism and Magyar domination of Hungary's

non-Magyar population, the ruling élites observed neither the letter nor the

spirit of the nationalities agreements. Over the years a nationalism which

had been originally liberal in character began to identify itself wholly with

the traditional Magyar sense of national mission, which viewed the Magyars'

historic task in the second half of the nineteenth century as pioneering the

new bourgeois economic, social and cultural progress in eastern Europe and

the Balkans and transmitting the achievements of western European

civilisation to its peoples. The aristocratic majority within the ruling

élite dreamt of a Hungarian Empire which would arise when multi-national Hungary had

become a Magyar nation state which would eventually become the dominant

factor in the Habsburg monarchy. Arguing on the basis of its historical

legitimacy a rampant nationalism developed which aspired to a nation state,

recognising only one nation, i.e. the Hungarian 'political nation', within

the frontiers of historic Hungary.

Establishing Hungary's

territorial integrity, political unity, the Magyar character of the state and

Magyar supremacy, or at least that of the Magyar ruling class, remained a

categorical imperative for all political parties and groupings up to 1918.

All other aspects of modernisation and democratisation, even the extent to

which national selfdetermination should be achieved, came second. The

Hungarian ruling élite thus ignored the national, political individuality of

the country's non-Magyar peoples and believed that neither collective rights

for the nationalities nor the slightest degree of compromise on the question

of administrative territorial independence were compatible with the 'idea of

a Hungarian nation state'. They believed that recognition of individual

equality for non-Magyar citizens, modest concessions regarding the use of

their native languages and the guarantee of autonomy for the minority

churches had already reached the limit of what the Hungarian nation state

could reasonably concede.

In the Liberal Party, which emerged after

the merger of Deák's party with the left Centre Party, the tone was set by

the county aristocracy who in calling for the inevitable development of the

Hungarian nation state, demanded complete Magyar supremacy in national life

and the curtailment of the politically and culturally privileged position of

the non-Magyar peoples. The protests of the national minorities against

Magyar unwillingness to acknowledge their distinct national identity and the

refusal to grant them selfgovernment gave the government the welcome

opportunity to intensify its magyarisation policy and expel from political

life any non-Magyar citizens unwilling to accept assimilation. The Elementary

School Law of 1868 -- still the product of liberal spirit of 1848 -- introduced

compulsory schooling for all children from the age of six to twelve and

provided for subjects to be taught in the language of the local population.

However, the Education Laws of 1879, 1883 and 1891 made the teaching of

Hungarian compulsory in nursery and the elementary and lower secondary

school, since the view prevailed that complete linguistic assimilation would

also lead to total political integration, i.e. allegiance to the Hungarian

nation. The aims behind the legislation were persistently and successfully

implemented by the administration dominated by the Magyar gentry. The result

was that an important linguistic and demographic shift took place on a major

scale in Hungary

between 1867 and 1918.

The Rumanians, Ruthenes and Slovaks, in

particular, suffered from this intolerant policy towards the country's

minorities. As early as 1875-76, several Slovak high schools were closed down

and the Adult Education Association (Matica Slovenská) was banned. All

teachers in minority schools had to provide proof of their ability to teach

the Hungarian language and other sub in Hungarian. The influence of Hungarian

was energetically promoted in all areas of public life, while the public use

of non-Magyar languages rapidly declined. Whereas approximately 10 per cent

of all civil servants belonged to the population's non-Magyar groups in 1910,

Hungarian was spoken as a first language by 96 per cent of civil servants and

91.2 per cent of all state employees. Although about a fifth of citizens

registered as a 'native Hungarian speaker', many may well have been in fact

bilingual, having been only recently assimilated and still in the process of

being integrated. Whereas, in 1880, only 14 per cent of Hungary's

population could speak Magyar and at least one other of the country's

languages, by 1910 the figure had risen to as high as 23.4 per cent.

Since the peoples of the Carpathian Basin

occupied areas of settlement which considerably overlapped, it was not only

the magyarisation measures ordered and encouraged by the state which resulted

in a spontaneous process of assimilation, but Hungary's economic growth and

the accompanying changes in the social structure wrought by urbanisation and

greater mobility. Between 1880 and 1910 some 2 million people were drawn into

the Hungarian orbit. Since positions of importance in Hungary's political,

economic, cultural and social life were still dominated by the Magyar ruling

élites, considerable advantages were to be gained if one acknowledged one's

Hungarianness. After 1880, Hungary's 700,000 Jews, who had been granted full

and equal civic rights as late as 1849 and 1867, thought of themselves as

Hungarians. The same was true of 600,000 Germans, 200,000 Slovaks and 100,000

Croatians, whose common religion and similar cultural and historical

traditions facilitated the process of assimilation. However, the social

cohesion of the Rumanian and Ruthenian peasant communities, which still lived

a very traditional life, formed an effective protection against magyarisation

measures. The higher a citizen climbed on the social ladder, the more likely

he was to change his national identity. A significant number of the middle

class, especially the intelligentsia and the majority of businessmen in trade

and industry, were assimilated citizens who played a crucial role in the

development of Hungarian bourgeois society and made an essential contribution

to the country's economic development, the adoption of western civilisation's

achievements and the development of urban life. In literature and the arts,

science, politics, the economy and the church, the newly assimilated

citizens, accepted without reservation by the government and a nationalist-

minded society, found great scope for participation and, by their efforts,

contributed to the strengthening of a sense of Magyar national pride.

Hungary's Jews, in

particular, were especially rapidly assimilated. At the time of the 1787

census during the reign of Joseph II, they had numbered 83,000, i.e. just 1

per cent of the total population. But, as a result of rapid immigration from Galicia and Moravia their number increased to 253,000

by 1850 (1.9 per cent) and 552,000 by 1869 (3.6 per cent). By the

emancipation laws of 1849 and 1867 the Jews had recently been freed from

political and economic discrimination. They were no longer excluded from

owning property, holding public office or forming guilds. They were also now

accorded full civic rights. From humble beginnings as moneylenders, grocers

and retailers of livestock and agricultural produce, they used the generously

offered opportunities for earning money which the gentry had ignored,

demonstrated their willingness to be integrated and consequently underwent

linguistic assimilation from Yiddish to Magyar via German. Zionist ideas were

relatively uncommon. The desire to advance socially by joining the emergent

middle class, their gratitude for the law's protection and the wide scope for

activity available to them turned them into convinced supporters of the idea

of a Hungarian nation state. Since most of the impoverished gentry and those

of the nobility, who were now forced to earn a living, viewed the civil

service as the only respectable form of employment, the Jews, who were

concentrated in the rapidly growing cities, did not represent competition for

their positions and livelihood. In the absence of a Hungarian middle class,

they provided a kind of surrogate middle class of small and large-scale

businessmen, lawyers, doctors and intellectuals. The Jews also made their

mark on the country's economic development as directors of banks and large

enterprises. In 1910, they numbered 932,000, i.e. 4.5 per cent of the

population, of whom over 75 per cent spoke Hungarian as their first language.

The percentage of Jews in the urban population amounted to as much as 12.4

per cent; in the bigger cities they comprised over 20 per cent of the

population. Budapest

with 23 per cent had the largest Jewish community.

Whereas a vociferous antisemitism dominated

Austrian public opinion at the turn of the century, the Hungarian government

tried to suppress any anti-Jewish movement from the outset. Early in the

1880s, the growth of nationalism was accompanied by the appearance of an

antisemitism which spread rapidly among sections of the gentry and the petty

bourgeoisie. It found its release in 1883 in the Tiszaeszlár ritual murder

trial. The court rejected the entirely unfounded allegation that the Jewish

community was responsible for the disappearance of a Christian girl.

Outbreaks of anti-Jewish violence, vigorously opposed by the government,

occurred in several counties, fuelled by superstition and other sinister

motives. A National Antisemitic Party ( Országos Antiszemita Párt) founded by

Gyözö Istóczy on 6 October 1883, succeeded in winning seventeen seats at the

parliamentary elections of 1884. But by 1890 this party had again disappeared

from the political scene. Although there continued to be a groundswell of

antisemitism, particularly among the peasantry, which, encouraged by the

poorer Catholic clergy, made its appearance on several occasions, it found no

response in the majority of the population. The spread of a pro-Magyar

nationalism among Jews in recognition of the government's attitude and in

gratitude for their protection in no way arose from a sense of opportunism --

as was the case with other assimilated groups. Instead, it was fostered by a

doubtless genuine sense of allegiance to their adopted country which was

often enthusiastically expressed.

The greatest opposition to the policy of magyarisation

came from the Rumanian inhabitants of Transylvania.

Initially led by the Orthodox archbishop, Andreiu Saguna, they wanted a

guarantee that the rights of the Rumanian

Church would be

protected. They also desired recognition of their equal status with the

principality's Magyar and German settlers, especially since the latter were

always represented in the Budapest

parliament by twelve or thirteen deputies. Disagreement became more acute

after 1881 when the Rumanian National Party (Román Nemzeti Párt) in

Transylvania demanded that the principality be once more restored as an

autonomous Crown territory, thus abolishing the union with Hungary. This

led Magyar political leaders to accuse the Rumanians of irredentism. Magyar

desires for greater centralisation, which subsequently became more noticeable

in Transylvania, caused the Rumanians to put

forward even more radical demands. Two possible schemes for separation from Hungary were discussed by the Rumanian

Cultural League, founded in Bucharest

in 1891. The preferred solution of the union of Transylvania

with the Rumanian kingdom, did not, however, appear feasible in terms of

foreign policy. The alternative proposal was that submitted by the

Transylvania Rumanian deputy, Dr Aurel Popovici. He wished to see Transylvania incorporated into a ' United Federation of

Greater Austria', envisaged as a separate federal state. Further

federalization of the Dual Monarchy appeared to offer the only prospect of

success against growing Magyar pressure. It also seemed to be the only way to

defuse the national conflicts which were swelling up in the Habsburg Empire

and thus guarantee the continued existence of Austria-Hungary. But, after the

plans of the Austrian government under Hohenwart and Schäffle to reorganise

the Dual Monarchy on a trialist basis by granting the Kingdom of Bohemia

'fundamental laws' had failed in the face of Hungarian intransigence,

Budapest could not be expected to support plans for a federation as a

precondition for realising equality of rights among the nationalities.

By the internal Hungarian-Croatian

Compromise of 1868 the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, which had initially wanted to

regulate its position in the monarchy on the basis of a personal union, was

granted far-reaching constitutional autonomy and special status within Hungary. As a

result the Hungarian government's magyarisation measures were not implemented

here to the same degree as in other areas inhabited by national minorities.

It was thanks to the patient labours of Bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer, for

many years leader of the Croats and imprisoned on account of his 'Illyrian' patriotism on religious, political

and cultural matters, that, with the founding of the university and a science

academy in Zagreb,

centres had been established to defend national and spiritual independence.

When, in 1883, the growing pressures of the government's magyarisation policy

sparked off demonstrations, the new Croatian governor, Count Károly

Khuen-Héderváry, successfully pacified Croatia in line with the

Hungarian government's ideas. By supporting the Serbian nationalist movement

and the Serbian parties he skilfully exploited the rivalries between the

different South Slav groups in order to play them off against each other. By

these means he succeeded in wrecking the plans of Ante Starčević's

Croatian State Party and its successor, Josip Frank's Pure Right Party, to

transform the Dual Monarchy into a triple monarchy by creating a Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

enlarged by the acquisition of Dalmatia and Fiume.

When the conflict between the Habsburg

monarchy and the Hungarian right-wing parties escalated in 1903, the Croatian

political leaders showed that they were prepared to cooperate more closely

with Vienna.

But when the Emperor rejected their offers, the Croatian opposition, led by

Ante Trumbić and Frano Supilo, completely swung round, largely accepting

as its own the demands of the Hungarian Independence Party contained in the

Fiume Resolution of 4 October 1905. The Monarchy's Serbs now rushed to

support the new policy of the Croatian opposition in the Resolution of Zara.

In contrast, against a background of growing conflict between Hungary's

nationalities, the Croatian People's and Peasant's Party (Hrvatska

Pučka Selječka Stranka), founded in 1904 and led by Stepan

Radić -- without doubt the most important Croatian politician of the

period -- came out further in favour of a federal system for the Monarchy,

without, however, being able to effect any change in the long-entrenched positions

or in Hungary's policy towards the Croats, which was conducted with growing

intransigence amid an atmosphere poisoned by the Austrian annexation of

Bosnia in 1908, the high treason trial in Zagreb (Agram) and the Friedjung

trial in Vienna. the anti-Austrian movement, encouraged by Serbia, which

aimed at destroying the Dual Monarchy by creating a pan-Slav empire in the

Balkans could, however, appeal only to a section of the relatively small

intelligentsia, in particular the student youth. The loyalty of the vast

majority of Croatia's

predominantly agrarian population towards the Empire and its ruling dynasty

remained undiminished until the end of the war.

Around 1880, Hungary experienced a wave of

emigration. This was not simply motivated by economic conditions, but by the

desire to escape the government's repressive measures against the country's

minorities. By 1913, over 2 million people had gone overseas. The number of

Magyars who emigrated was far fewer than the average for the whole country, especially

since many returned to their homeland at a later date. On the other hand,

many Slovaks, Ruthenians and South Slavs, who were proportionately

overrepresented among emigrants -- mainly small peasant farmers and craftsmen

-- hoped to escape for good the material distress and limited scope for

social mobility in Hungary. Since many of the immigrants who came to settle

in Hungary, mainly from Moravia, Bohemia, Galicia and Italy, belonged to the second or

third generation to be fully magyarised, these major population movements

eventually resulted in an increase in the number of Magyars and their number

relative to the size of the total population.

Despite all its shortcomings, it is still

possible to describe the treatment of national minorities in Hungary before the First World War as

relatively liberal and tolerable compared with contemporary conditions in

eastern and south-east Europe. Despite the

pecking order imposed by Magyar national sepremacy and the repression of the

national minorities. Hungary offered reasonably good opportunities for development and

a degree of security before the law to all the ethnic communities settled on

its soil -- provided they were prepared to respect the principle of the unity

and indivisibility of the 'Hungarian political nation'. But the quarrel

between the nationalities -- above all the conflict between the ruling Magyar

nation and Hungary's

non-Magyar population -- grew more acute around the turn of the century to

the extent that the Habsburg Expire collapsed, not least because of its

failure to solve the nationalities problem.

Social stratification and economic

development

Until the middle of the nineteenth century Hungary's social order was, like Poland's,

dominated politically, socially and economically by a large nobility and

distinguished by the presence of an exceptionally large rural proletariat

within the peasant class. The undeveloped urban bourgeoisie was relatively

unimportant in terms of its size and role in society. Although the 1848

Revolution had witnessed a change from a feudal society based on estates to a

constitutional monarchy and had brought about the abolition of traditional

obligations and the establishment of full civic equality, the dissolution of

the feudal social structure proved to be a long and slow process. The

legislature and the executive remained in the hands of the aristocracy and

landowning gentry which saw itself as the only social class capable of

governing.

According to careful estimates, 6 per cent

of the population were members of the nobility; among the Magyars the figure

was 12-13 per cent. Some 200 aristocratic and wealthy landowning families,

together with approximately 3,000 wealthy families of the middle-ranking

landowners, who as 'thousand hold men' owned estates of over 575 hectares

(the so-called bene

possessionati), dominated public life by virtue of their education and

income. Their mentality and system of values, their liberal-nationalist

politics and their aim to bring about what they saw as necessary democratic

reforms in Hungary in a manner that would preserve their own social and

political position of predominance, dominated attitudes, thinking and

Hungary's way of life well into the twentieth century. The section of the

landowning élite which was able to retain and modernise its property of 100

to 500 hectares saw itself as the true representative of the Hungarian nation

and custodian of the Hungarian national identity. Comprising around 5,000

families, this gentry class had a firm social basis and exerted a crucial influence

in the government, parliament and the county councils. Its chief

preoccupation was managing its estates which comprised in all more than a

third of the country's cultivable land. Those of their number who were more

skilled in business, invested their capital profitably in banks and industry.

Most members of the old landed nobility,

however, failed to adapt to the new economic conditions which followed

peasant emancipation. They ran up debts, became impoverished and lost their

estates entirely or in part. The economic decline of the former

middle-ranking and petty nobility, referred to as the 'gentry' from the early

1870s onwards, forced many of its 500,000 or so members to earn a living in

the country's expanding bureaucracy, from the legal system, municipal

councils and county administrations to government posts, the army officer

corps, gendarmerie and police force. Here they were able to preserve their

aristocratic lifestyle and position of social predominance. Members of the

gentry, many of whom were related by marriage, controlled about half the

posts available in the government ministries and three-quarters of those in

the county administrations. In order to maintain their positions they

supported the system of the Dual Monarchy and the policies of the government

party. In the absence of a broad, economically independent and self-confident

middle class, the gentry formed the nucleus of an emergent urban bourgeoisie

comprising assimilated groups and Magyar social climbers of petty-bourgeois

or peasant origin.

After 1848 the peasants of noble status

merged with the free peasantry and emancipated serfs to form a single social

class of peasants.

In the early modern period the population of

Hungary's

towns was mainly made up of non-Magyar immigrants, of whom the Germans formed

the largest single community. In the course of the nineteenth century they

were increasingly joined by the Czechs and the Jews, who were undergoing

rapid assimilation. This petty bourgeoisie, which earned its living from the

craft industries and small trades took decided advantage of the opportunities

for social advancement opened up by economic progress after 1850 and modelled

itself socially on the gentry. But only in exceptional cases did its members

succeed in acquiring great wealth. Hungary's Jews soon distinguished

themselves as entrepreneurs by their enterprise and willingness to take

risks. They were involved not only in marketing and exporting agrarian

produce, but invested their capital in industry, railway construction and the

banking system. By the turn of the century a financial oligarchy of about

fifty families had developed. These families controlled all the key positions

in Hungary's

rapidly developing economy, but did not challenge the social predominance of

the aristocracy. Indeed, they tried to ape their lifestyle in external

appearances which went as far as the enoblement of 346 Jewish families of the

haute bourgeoisie. Twenty-eight were made barons and many acquired large

estates, with the result that before the First World War Jews owned a fifth

of Hungary's

major estates. But although some Jews were represented in the Upper House,

the financial bourgeoisie from which they emerged was content to share power

only indirectly. The strong Jewish element in the middle class and

university-educated intellectual élite contributed to the fact that the

increasingly confident city dwellers began to turn away from modelling

themselves on the gentry in the twentieth century and developed their own

bourgeois lifestyle, value system and codes of behaviour. The town dwellers'

political views tended to be liberal-nationalist. The greatest possible

measure of Hungarian independence within the framework of a monarchy

transformed into a purely personal union, economic freedom, the guarantee of

universal, equal suffrage and the secret ballot headed their list of demands.

The lower classes in the towns, poor

craftsmen, downwardly mobile petty nobility and rapidly growing industrial

proletariat were nationalistic in outlook and therefore anti-Austrian in

their attitudes. They supported the movement for Hungarian independence. For

a long time the state bureaucracy's repressive and coercive measures

succeeded in preventing the spread of radical ideas which sprang from the

social misery and denial of civic rights, but it did not feel obliged to take

effective measures to remedy the miserable conditions. The social class of

industrial workers living in the urban areas which attracted migrants rose

from 182,000 in 1857 to 955,000 in 1910, but the specific character of Hungary's

industrialisation meant that the nucleus of this class was provided by

skilled workers from abroad. The ruthlessly exploited unskilled workers and

day-labourers were often only seasonal workers, of whom more than half worked

in large factories and a third in Budapest.

Women and children supplied two-fifths of the workforce. Workers from the

districts inhabited by the national minorities, mainly Slovaks and Germans,

were also quickly caught up in the process of magyarisation, so that the

proportion of Hungarian employees in industry rose to 60 per cent (in Budapest to 80 per

cent) within the space of a few years. Since real wages failed to grow

adequately, the workers in the twentieth century were increasingly prepared

to form trade unions and organise themselves politically. This development

and their readiness to back their demands by strike action could not be

halted despite minor concessions in labour law, the introduction of a social

insurance system and sickness benefits and a shortening of the working day by

one to two hours.

Urbanisation on a major scale began in Hungary in

the second half of the nineteenth century. Growth benefited the capital, Budapest, which came into being in 1873 as a result of

the original German settlement of Buda merging with Pest and the old

mediaeval town of Óbuda.

Of its 880,000 inhabitants in 1910, 86 per cent spoke Hungarian as their

first language. The city's elevated position as Hungary's economic and cultural

capital was underlined by the fact that Greater Budapest with its ribbon

development of suburbs contained only 5.1 per cent of the country's total

population but 28 per cent of its workforce and two-thirds of its major

industry. Hungary's

provincial centres suffered as a result of the capital's dynamic growth. Only

Szeged had a

population exceeding 100,000. A third of Hungary's towns, including half

of its major cities with over 50,000 inhabitants remained typical market

towns with a pronounced village character, especially in the outlying areas.

The majority of the country's inhabitants continued to earn their living from

agriculture. By 1910, however, a good third of the population already lived

in 145 urban settlements of over 10,000 inhabitants. As a result of the rapid

process of assimilation 78.6 per cent of them spoke Hungarian as their first

language.

Over 50 per cent of the population, however,

lived in small villages, a further 15 per cent in isolated farmsteads and in

farms on the open Puszta grasslands belonging to the large estates. As a

result of rapid economic growth, the number of persons employed in

agriculture showed a sharp and steady decline from 75 to 60 per cent between

1869 and 1910. At the same time, however, the proportion of the workforce

employed in mining, crafts and industry rose from 10 to 18.3 per cent, that

of white-collar workers in commerce and transport from 4 to 6 per cent and in

the services sector from 13 per cent to 15.6 per cent. Hungary

contributed almost half the Dual Monarchy's total agricultural production,

i.e. 47.8 per cent. Although the redistribution of common land and forest

after 1849 was often accompanied by peasant unrest, the majority of small

tenants acquired a farming strip of a few furrows (1hold = 0.5754 hectares). By 1910 the size

of the rural proletariat, the most populous class of poor peasants with small

holdings, grew to almost 4 million as a result of the division and parcelling

out of land. During the decades of major railway construction, which

witnessed impressive improvements in flood and drainage control in the Tisza

and Danube valleys (available land for

cultivation increased from 8.7 to 12.8 million hectares) and rising grain

prices, they were able to earn a modest living as seasonal workers and

day-labourers. But after 1890 they became gradually impoverished and many

were forced to emigrate. After 1910, the introduction of imported threshing

and reaping machinery, together with a more efficient iron plough, meant that

the lowest category of peasantry who owned less than 5 hectares and depended

on secondary earnings, could at best find secure employment for only 88 days

of the year. The result was that this group, which constituted two-thirds of

the peasantry and owned about a quarter of the land and two-fifths of the

country's livestock, also experienced increasing hardship. Only the quarter

of a million or so middle-sized farms of up to 10 hectares were able to

survive to some extent through stubborn and persevering efforts to cultivate

the land, switching from extensive animal husbandry to intensive wheat or

maize growing or specialised areas of production like market gardening,

viticulture, poultry-keeping and tobacco growing. Between 1851 and 1895 the

number of farms of less than 50 hectares, which were managed not only by major

producers but by the impoverished and declining middle-ranking aristocracy,

trebled from 65,800 to 188,300. Despite the immense changes in farming

methods and rural society, the traditional structure of village life

continued into the twentieth century. Traditional ways of earning a living by

farming, together with a traditional mentality and way of life continued in

the prescribed manner of feudal society.

Although 99 per cent of Hungary's

landowners were peasants, they owned only 56 per cent of cultivable land,

barely half of the available farming machinery and 80 per cent of the

country's livestock. The state owned between 6 and 7 per cent of the land,

but 33 to 35 per cent of cultivable land remained in private or church

ownership, estates sometimes equalling whole English counties in their

extent. Great landed estates were often organised as indisposable entailed

estates which passed to a male member of the landowning family according to

fixed rules of inheritance. This had enabled the Esterh;izys, the Counts of

Schönborn, the Prince of Coburg-Gotha and Austrian

archdukes to avoid the break-up of their estates. Among the episcopacy, the

Bishop of Nagyvárad, and Archbishops of Esztergom and Kalocsa controlled the

largest estates on which thousands of day-labourers and servants lived. They

worked as agricultural wage-labourers in a hierarchically organised system of

managed estates, often completely cut off from the outside world. This

inequitable distribution of landed property remained essentially unchanged

before 1918, although some changes did occur by 1945.

After the upward economic trend in

agriculture in the 1860s, when Hungarian grain and cereal sales to western

Europe and Austria

produced substantial profits, the economic crisis of 1873 caused an initial

price fall. Competition from cheap imports of foreign grain and protectionist

policies meant that this lasted until the 1880s and reduced profits by

two-thirds. High production costs caused by backward farming methods, natural

disasters and the almost wholesale destruction of viticulture caused by the

spread of phylloxera ruined many a landowner. The number of holdings which

owners were forced to sell and parcel out showed a worrying increase as did

the collapse of some 10,000 farms. With the help of state subsidies and

protective tariffs, support was given to the introduction of modern farming

methods which benefited the large estate owners in particular through the use

of machinery and increased productivity. The introduction of intensive crop rotation,

improved seedlings and the increased use of artificial fertiliser resulted in

the doubling of the yield per hectare, although this lagged far behind that

of western Europe. A gradual return to cereal production, switching to hoed

crops and plants for industrial uses and the spread of dairy farming and

livestock fattening led to an increase in the profits of the larger farms

while the smallholders and smallest peasants could barely survive and were

often reduced to the status of landless labourers. The new economic

conditions in agriculture in the twentieth century, especially after the

imposition of high agricultural tariffs in 1906, also benefited

middle-ranking and large-scale farmers, but at the same time consolidated the

dominant position of the vast estates and ruled out any redistribution of

land which might satisfy the peasants' land hunger and the claims of the

destitute rural population.

What particularly characterised the period

between 1867 and 1914 was, however, the rapid growth of industry, commerce

and transport in relation to agriculture, resulting in a profound

transformation of Hungary's

socio-economic structure. Thanks to an annual average growth rate of 2.8 per

cent, Hungary was

gradually able to close the gap with Austria and by 1914 already

accounted for 28.2 per cent of the Habsburg Empire's total industrial output.

But Hungary also had to

accept an increase in its share of the Dual Monarchy's common expenditure

which rose by 6.4 per cent to 36.4 per cent, while Austria's contribution fell from

70 to 63.6 per cent. Although agriculture still accounted for two-thirds of Hungary's

national income in 1913, the share contributed by industry and trade had more

than doubled since 1870. This was due not least to the foreign investment

capital which had flowed into Hungarian railway construction, mining,

large-scale estates and the creation of banks. This, together with the

increasing availability of Hungarian capital, benefited large-scale industry.

About half the foreign capital of 800,000 crowns invested in the Hungarian

economy was Austrian. Access to the Dual Monarchy's. wider domestic market

greatly later benefited Hungary's

economic development because only this common market could absorb the

increased production, given the Hungarian market's low level of demand. In

addition, about 80 per cent of Hungary's trade was transacted

with the Austrian half of the Empire.

Railway construction was an important factor

in the modernisation of the Hungarian economy. The railway network grew from

2,200 kilometres in 1867 to 22,000 kilometres in 1913. Freight and passenger

traffic developed extremely rapidly with the growth of Budapest as a major railway junction. The

building of railways also benefited the domestic iron industry and

manufacture of machinery, while guaranteeing employment for countless railway

navvies. The food industry, in particular the flour industry, attained a

leading position in Europe. In the timber,

paper and leather industries the trend towards large-scale production was

also pronounced. Coal and iron-ore production showed a dramatic growth-spurt

and encouraged the expansion of the machine industry, which continued to do

well with its traditional products, the manufacture of agricultural and

milling machinery. Thanks to considerable state subvention the textile

industry also experienced a marked boom, although, faced with superior

Austrian competition, it could only cover a third of the needs of the

domestic market.

The economic trend towards larger-scale

enterprises continued unchecked. Industrial concentration was encouraged by

foreign capital which in 1880 owned two-thirds of Hungarian industry, in 1900

a half and in 1913 about 35 per cent. The biggest firms, which accounted for

only 0.5 per cent of all enterprises, employed 44 per cent of the workforce

and produced two-thirds of the country's total manufacturing output. Business

consortia and cartels, formed in various

branches of industry, strengthened the influence of the new banks and

industrial monopolies. The craft manufacture of consumer goods, in contrast,

showed a marked decline. Craftsmen and small tradesmen found themselves

living through a period of crisis. Hungary

failed to attract the manufacture of more modern and future-orientated

products, because Austria-Cisleithania's more advanced industry, shielded by

high tariffs and well attuned to its own level of demand and price structure

within the monarchy as a whole, managed to forestall Hungary's innovations, thus preventing any

major structural changes within Hungary's established industrial

structure. This conduct resulted in a less balanced and less favourable

industrial development in Hungary,

but did not justify the supposition of Magyar historians that Hungary had been completely exploited because

of its imbalance of trade with Austria. During the initial phase

of investment-intensive modernisation, Hungary was able to rely on the

Monarchy's large market and the import of Austrian capital. It could sell its

agricultural exports to Austria

during the agricultural crisis, and, thus secured, hasten the dynamic growth

in the leading sectors of the Hungarian economy, namely agriculture and

foodstuffs. Hungary was by

no means an economically exploited country held in economic subservience to Austria, but

as it was modernised had to adapt to prevailing conditions in the Monarchy

and accept a delay in its socio-economic transformation and the prolongation

of its traditional economic structure. Although the gap with the western

industrial nations was, therefore, only slightly reduced, Hungary in

1914 stood on the threshold of the changeover from a purely agrarian-based

economy to an industrial nation.

Religion, education and culture

From the time of its

successful Counter Reformation under the cardinal-primate, Pétér Pázmány (

1570-1637) Hungary, which was often referred to as 'Mary's Kingdom' ( Regnum Marianum), was regarded as a typical Catholic country. In fact, only

56.14 per cent of its population in 1880 were practising Catholics. In 1910

the figure was 58.95 per cent. But, since the Catholic bishops had also

exercised temporal power, Roman Catholicism had long been the established

state religion and the monarch had been accorded the right of patronage, the

appointment of archbishops and bishops, the creation of new dioceses and the

general promotion of the Catholic faith well into the twentieth

century. Subject only to papal approval, the Catholic Church exercised a

disproportionate influence. It was only after the Emperor Joseph II's

tolerance edict of 1781, which first permitted freedom of worship and allowed

non-Catholics to hold public office, that the last remnants of the state's

attempts at recatholicisation came to an end. Catholicism was also able to

salvage its position of predominance beyond the 1848 Revolution. Since many

of the 'insurgents' had been non-Catholics, the Church enjoyed the special

protection of the central government in Vienna

until 1867. Although the position of the state vis ŕ vis the Church was

somewhat weakened by a Concordat concluded in 1855, no attempt was made to

bring about the complete separation of church and state. In 1868 this

Concordat was ruled to be invalid for the territories of the Hungarian crown

and the Placet regium was reintroduced. All administrative

and religious affairs which affected future relations between church and

state became the responsibility of the minister for education and religion.

These measures resulted in attempts to

establish lay-control of the Church in Hungary, a development which

gradually eroded the Catholic Church's privileges and brought about genuine

equality of status for the country's other denominations. It especially

benefited the Calvinists and Lutherans, who in 1880 made up 30.75 and 4.04

per cent of the population respectively. Although only three-tenths of the

country's Magyars were Calvinists. Calvinism was regarded as the 'Magyar

religion' since the significant part played by its adherents in political and

cultural life, and thus their scope for shaping the structures and behaviour

patterns of Hungarian life, far outweighed their numbers as a percentage of

the population. Adherence to the Lutheran faith (based on the Augsburg

Confession), which was especially widespread in Transylvania, Slovakia

and the German community caused it to be referred to as the 'German religion'

in everyday speech. Already in possession of the equal rights accorded to

legally recognised denominations, as decreed in 1848 (Law XXI of 1848), the

protestant churches tried to build on the increased autonomy granted, them after

1867. They created a modern church organisation and began to take an active

part in public life which was increasingly dominated by liberal values. From

1885 onwards, their dignitaries had seats and a voice in the Upper House. As

a result of substantial Jewish immigration, the proportion of Jews in the

population also increased from 5.69 per cent to 7.2 per cent between 1880 and

1910. The Jews consequently exerted a growing influence on Hungary's

economic and spiritual life. A clear majority of Rumanians, Serbs and

Ruthenes adhered to the Greek Orthodox Church and a smaller number to the

Greek Catholic or Uniate Church.

After 1867 the Catholic bishops were

unwilling to concede their powerful position without a struggle. The liberal

Education Law of 1868 expressly allowed denominational schools, although at

the same time it increased state control of education. The church authorities

continued to be responsible for marriage ceremonies, the recording of births,

marriages and deaths and adjudication in all questions concerning marriage.

The Catholic clergy consistently ignored the government's directive that the

sons of mixed marriages should be allowed to follow the father's religion and

the daughter the mother's religion. Growing frictions and annoyance regarding

the splendid lifestyle of the bishops, drawn mainly from the petty-bourgeois

peasantry, caused the Szápáry government to take measures against alleged

'irregularities' in church politics in the summer of 1892. In this, the

government could rely on the support of broad sections of the middle class

and intelligentsia among whom religious indifference had become widespread

and who, in keeping with the liberal values of the period, favoured

reorganising church politics which had come down the centuries unchanged from

mediaeval times. Although the petty-bourgeoisie and the peasantry still

unhesitatingly obeyed their priests, a growing number of people sought to

satisfy their religious needs outside the framework of official religion.

Since the clerical camp even opposed the introduction of the citizen's right

to choose a civil marriage and the liberals wanted to see marriage ceremonies

and the recording of births, marriages and deaths become the exclusive

preserve of the state authorities and, alongside religious toleration, to

accord equal rights to orthodox Judaism and other denominations, church

affairs became the subject of open conflict between 1892 and 1894.

Mobilised by the clergy and conservative

aristocrats, the masses resisted any move towards reform and 'persecution of

religion'. In this, they were supported by the papal encyclicaConstanti

Hungarorum, specifically issued by Pope Leo XIII. However, the new

government, led by Wekerle and supported mainly by the protestant community,

the Jewish bourgeoisie, supporters of a secular nation state and the majority

of the Liberal Party, was able after lengthy parliamentary debate to push

through the new legislation which sanctioned compulsory civil marriages, the

state's right to keep public records and civic equality for the Jews. The

devoutly pious Emperor Francis Joseph made no secret of his rejection of the

new laws whose finalisation he postponed until 10 December 1894. Wekerle's

government, which he viewed as much too liberal, was dismissed on 14 January

1895. Two weeks later Count Nándor Zichy and Count Miklós Móric Esterházy

founded the Catholic People's Party ( Katolikus

Néppárt) to defend the Catholic Church's position and rights in Hungary while

at the same time creating a political mouthpiece for Catholicism.

Of even greater significance was the

movement for spiritual renewal within Catholicism initiated by the Professor

of Theology and later Bishop of Székesfehérvár, Ottokar Prohászka. By

adapting pastoral work to modern conditions and addressing urgent social

problems, this movement took account of the changes wrought by

industrialisation. The Church's return to its pastoral and socio-political

tasks was also accompanied by a readiness on the part of some sections of the

urban middle classes and the intelligentsia to embrace Catholicism actively

once more. The protestants also experienced a similar movement of renewal at

this time.

Even if, as a result of state legislation

and contemporary liberal attitudes, the earlier social and political influence

of the Hungarian churches was in relative decline in the years before 1914,

their say on important matters and opportunities for influencing political

and cultural life remained largely unaffected.

It was thanks to the personal involvement of

Hungary's first minister

for education and culture, the respected writer, Baron József Eötvös, that Hungary was

given an Education Law imbued with liberal values as early as 1868. This law

not only made education compulsory for all six to twelve-year-olds, but

provided for state-controlled elementary schools alongside existing

denominational schools. By 1914, the number of elementary schools increased

from approximately 10,000 to almost 17,500, of which 5,000 were state-run or

local government schools, each with one teacher or, in the case of 7,000

schools, several teaching staff. The number of children attending school rose

from 729,000 to 2,621 million. As a result of the government's use of

schooling in its forced policy of magyarisation the number of elementary

schools in which Hungarian was the language of instruction almost doubled

from 7,300 to 14,200. The number of grammar schools also rose by 87 to 213.

Lessons were taught in Hungary's

five non-Magyar languages in only forty-one of the grammar schools. Instruction

in the country's ninety-two teacher training colleges was exclusively in

Hungarian. Thanks to the improvement in basic education which benefited

around 90 per cent of all schoolchildren, illiteracy among the population

over six years of age fell from 55 per cent in 1867 to 31 per cent in 1914

and to 41.8 per cent for the total population in the same period. But the

national minorities had to pay dearly for this dramatic improvement in the

education system with the loss of their own languages as the language of

instruction. All subsequent laws, such as the 1883 reform of middle school

instruction based on proposals drafted by Agoston Trefort, disadvantaged the

nonHungarian languages. Little wonder, therefore, that 84.5 per cent of

candidates with university entrance qualifications and 89 per cent of those

attending university lectures were Magyars or spoke Hungarian as their first

language.

Hungary's system of

university and technical education was also systematically expanded. In 1851 Hungary had only 810 students, most of whom

studied at the university in Pest. By 1914,

the number had risen to 16,300. Students could now also study at Budapest's Technical

University (founded in 1872), in

Kolozsvár (Cluj) (founded 1872), Debrecen or

Pressburg ( Bratislava)

(founded 1912). Legal (33 per cent), medical (19 per cent), humanities (10

per cent) and divinity (10 per cent) studies enjoyed particular popularity.

Only 22 per cent of undergraduates chose to study the natural sciences,

technical studies or economics. Since the proportion of students from

working-class and peasant families was below 3 per cent, the majority of

students were sons of the wealthy nobility (around 50 per cent) and the urban

bourgeoisie (over 40 per cent). Jewish students were overproportionately

repre- sented amongst graduates.

The period of 'national revival' had already

created the preconditions for the growth of Magyar national culture before

1848. The National Museum in Budapest,

whose benefactors were the father and son, Széchenyi, the National Library

(1802) and the forerunner of the Hungarian

Academy of Sciences (

1825), which concentrated on the study of languages in the interest of

creating a sense of national identity, had been followed by the establishment

of a National Theatre in 1837. After the Compromise of 1867 the so-called

'national' disciplines, now freed from romantic dilettantism, were able to

build on these foundations. Collections of historical source materials, the

first compilations of Hungarian history and a history of the Hungarian

language and its literature began to appear -- although still mainly

conceived in a conservative nationalist spirit. With the opening of research

institutes and cience laboratories, involving considerable financial outlay,

the natural sciences and technical disciplines underwent rapid growth

stimulated by international developments. The study of physics and the Budapest school of

mathematics achieved particular distinction.

The period of the 'national classicism' of

the patriotic school between 1840 and 1860 saw Hungary's national literature

reach its first apogée which was linked with names like Sándor Petőfi,

József Eötvös and János Arany. Following a period of relative academic

stagnation and an output of derivative works a general revival took place

from the beginning of the twentieth century onwards, which, parallel to

general European cultural developments, embraced all areas of culture. Endre

Ady and Zsigmond Móricz set new standards in literature which were reflected

in the paintings of the Nagybánya school and in the later post-impressionist,

avant-garde work of the so-called 'Eight', Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály, who

returned to traditional folk melodies for their inspiration, brought new life

to Hungarian music and made a significant contribution to the development of

modern music. Theatre, opera and operetta found an enthusiastic and

knowledgeable public. Around 900 daily newspapers, numerous public libraries

and many publishing houses catered for an interested readership.

If art and culture in Hungary had

been dominated by Austrian and German influences before the turn of the

century, the new liberated currents of Hungarian intellectual life in the

years before 1914 turned increasingly to British and French models. As well

as the national element, there was a strong sense of social and political

commitment which sought to influence the intellectual creative process in a

radical and democratic spirit.

THE BEGINNINGS OF NATIONAL SELF-GOVERNMENT UNDER ANDRÁSSY AND TISZA

The consolidation of internal politics

The vociferous and resolute objections which

many Magyars and most national minority leaders raised against the Compromise

of 1867 forced Andrássy's government to exercise extreme caution in dealing

with Hungary's

outstanding political problems and show all parties a desire to compromise.

The introduction of a unitary centralist administration was given priority,

but not surprisingly met with resistance from the county administrations

which held on firmly to their feudal legacy and mostly opposed the

government. Since every attempt to pass parliamentary legislation was also

subject to the monarch's prior consent, the government and parliament's scope

for innovation remained relatively limited, although new legislation was required

in almost every sphere and draft proposals had to be submitted in advance to

the Emperor. The organisational principles and legal norms to be applied had

to observe the principle of the monarch's absolute rights. Since, moreover,

Ferenc Deák and his immediate colleagues pursued more liberal views than the

majority of the Compromise party, and the Hungarian nobility stubbornly

defended its traditional prerogatives, the expansion of the Hungarian state

apparatus and codification of the legal system came about only very

gradually.

At the lowest level, particularly in the