|

|

At the Diet of 1825, following a statement made

by one of the members on the need to encourage the use of the Hungarian

language and culture, a young aristocrat, count István Széchenyi, asked for

the floor. To help implement this aim, he offered a year's income from his

estates to found a Hungarian

Academy of Sciences.

His example was followed by others, and by the end of the Diet, the necessary

financial basis for the establishment of the Hungarian Academy

of Sciences was secured.

Széchenyi's speech at the Diet marked the

beginning of a new era, that of the Hungarian Reform Movement. Széchenyi

became an outstanding leader of this movement in the following years, the

initiator and active participant of a whole series of changes and reforms

which were to set feudal Hungary

on the road to bourgeois development.

Széchenyi's ideas for reform were supposed to

lay the foundations for the growth of general welfare. He believed that the

transformation from feudalism to bourgeois economy could be implemented

voluntarily and peacefully. He was anxious to see these inevitable reforms

take place under the leadership of the nobility and the large landowners. He

had no desire to alter the relationship between Hungary

and the Hapsburg dynasty; on the contrary, he wanted to make use of Austrian

capital for the economic transformation of Hungary. He elaborated his

political programme in influential books, but his practical initiatives also

gave a considerable boost to development. He participated in the introduction

of steamship navigation on the Danube,

encouraged mining, set up steam mills, and aided the construction of

railways. He was responsible for works regulating the waters of the Tisza and

the Lower Danube, and induced the Diet to pass a law for the construction of

the first permanent bridge across the Danube, the Chain Bridge in Budapest. He was the

first to propose the unification of the three separate towns of Buda, Pest and Óbuda.

The other great personality of the age, Lajos

Kossuth, made his first appearance in public life at the Diet of 1832 with

the publication of a newspaper - produced in mimeographed form - that

contributed considerably to the dissemination of liberal ideas throughout the

country.

The activities of the Reform Movement mobilized

the political life of the country. Chancellor Metternich, however, who

effectively held the reins of power in place of the sickly and feeble-minded

Ferdinand I, did everything he could to roll back the tide of liberal

resistance. But the views of Kossuth were becoming increasingly popular; by

means of modern journalism, he was able to win over the public to side with

his political views. The political programme of the Opposition Party

advocated the liberation of the serfs against an indemnity paid to their

lords, ended the nobility's privilege of not paying taxes, proposed the

gradual introduction of universal franchise and equality before the law. It

also advocated the abolition of the system of entailment, one of the most

ancient laws governing Hungarian feudalism, which stood in the way of the

development of a modern credit system.

The revolutionary spirit of the spring of 1848

gave a tremendous impetus to the course of events in Hungary. Having swept Paris, Berlin and Milan, revolution irrupted in Vienna as well. On March 15, a

revolutionary demonstration took place in Pest.

The writer Mór Jókai read the "Twelve Points" containing the

national demands for change, Sándor Petőfi recited his poem, the

"National Song", and a revolutionary mass meeting was held in front

of the National

Museum in which ten

thousand people took part. The Diet which held its session in Pozsony [now Bratislava] passed the

laws containing the reforms demanded by the opposition. The king gave his

assent, and the Viennese

State council appointed

count Lajos Batthyány, the chairman of the Opposition Party, to form the new

government.

The revolutionary wave that swept over Europe had paved the way for the bloodless victory of

the March revolution. But by the summer of 1848, the wave of

counter-revolution had won decisive victories, and the court in Vienna decided that the

time had come to take action against the Hungarian revolution. Jellacic, the bán

of Croatia devoted to

imperial interests launched an attack with an army of 45,000, crossed the

river Drave, and invaded Hungary.

The National Defence Commission elected by Parliament took over the

leadership of the resistance with Lajos Kossuth at its head. Kossuth promptly

set out on a recruiting campaign, and tens of thousands of people from the

towns and villages of the plains rallied to the battle-cry. The Hungarian

army, made up for the most part of the new conscripts, defeated Jellacic and

drove his army out of the country. Influenced by the events in Hungary, the Camarilla in Vienna compelled Ferdinand V to abdictate

in favour of Francis Joseph (1848-1916). Under the command of Prince

Windischgraetz, the offensive against Hungary began and on January 4,

1849 the imperial forces captured the capital. The Government transferred its

headquarters to Debrecen, and Arthur Görgey,

the commander-in-chief of the Hungarian forces, led his army through the

mountains of northern Hungary.

He arrived after a brilliantly executed series of manśuvres on the Upper Tisza, where the army was reorganised and

reinforced with newly recruited troops.

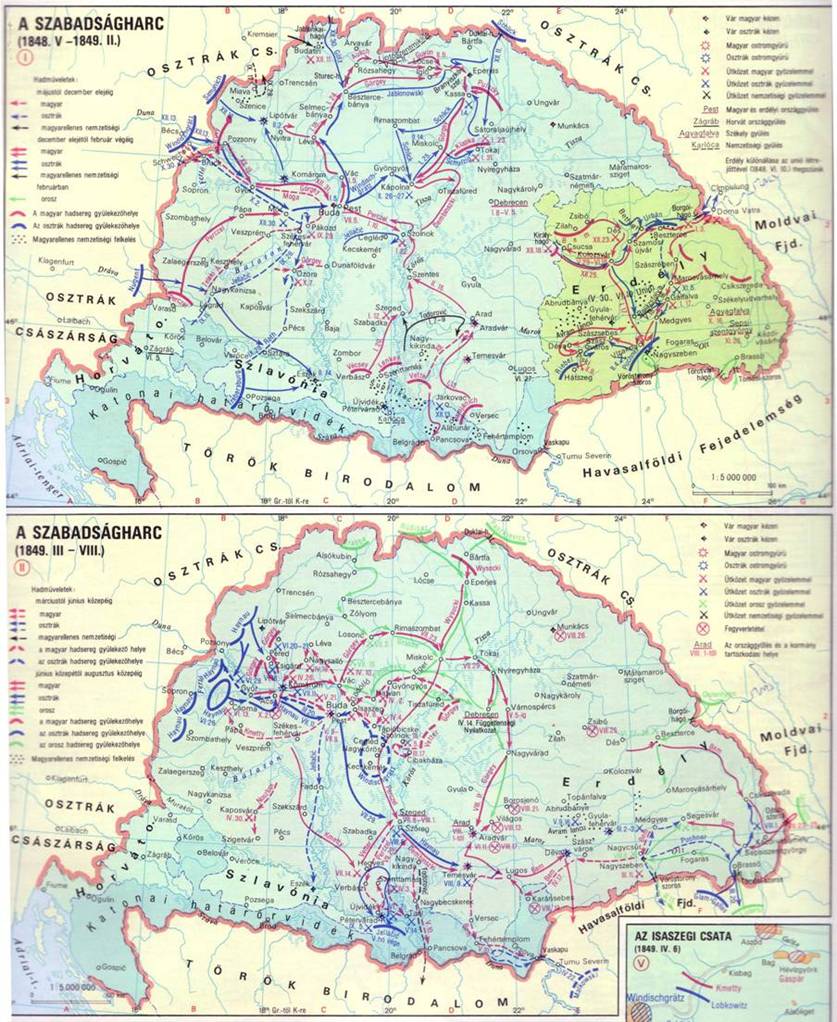

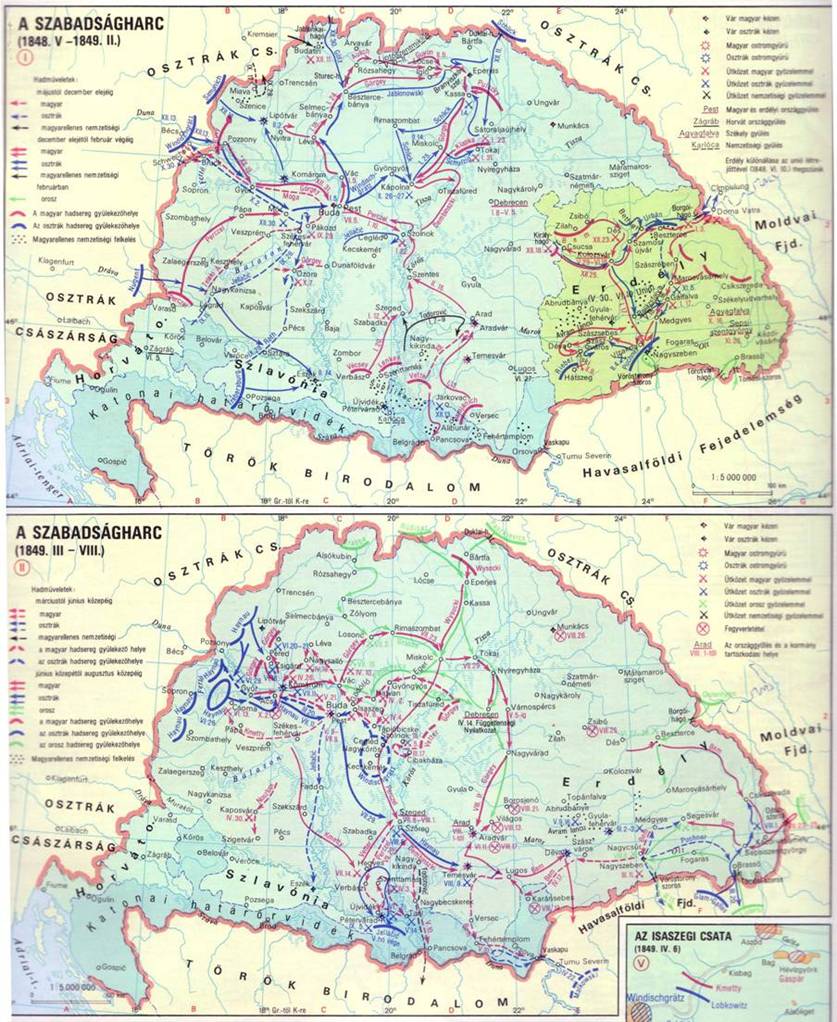

Map from Hungarian

Historical Atlas depicting

the War f Independence

/ 1948-49.

Click on the map for

higher resolution

The Hungarian forces, strengthened during the winter

months, launched an offensive in the spring of 1849. Supported by Polish,

Austrian, Italian and other volunteers, it drove the imperial forces out of

the country after a series of victorious battles. Following the marked

improvement of the military situation, Kossuth - with the support of the

radical wing in Parliament - forced through the dethronement of the Hapsburgs

and the proclamation of the independence of Hungary on April 14, 1849. He was

then elected the Governing President of the country.

Meanwhile, on the basis of their Holy Alliance,

the Hapsburg Court

presuaded the Russian czar to provide military intervention against Hungary.

The Hungarian forces were inevitably overwhelmed by the joint offensive of

the superior Russian and Austrian imperial forces. After many bottles, the

Hungarian war of independence was crushed. The poet Sándor Petőfi was among

those who fell in the battle of Segesvár [now Sigisoara]. The final battle at

Temesvár [now Timisoara]

was concluded by the Hungarian surrender to the Russian commander-in-chief,

Prince Paskievits, at Világos on August 13, 1849. Kossuth, together with many

other leaders of the war of independence, took refuge abroad. Fourteen

generals were executed at Arad [now Oradea], Count Lajos Batthyány was shot by a firing

squad in Pest, military courts sentenced

thousands to prison and to death, and tens of thousands of Hungarian soldiers

were forcibly conscripted into the emperor's army. A reign of terror engulfed

Hungary.

The Compromise

and Hungary

in the Dual Monarchy

Revolutions, including the unsuccessful ones,

nearly always force their victorious enemies to retain at least some of the

measures which were introduced by them. This is what happened in the case of

the 1848-49 Hungarian revolution and war of independence. Although the

political system introduced by the Minister of the Interior Alexander Bach

annulled the 1848 laws, it could not, however, nullify the most important

reforms, including the liberation of the serfs. So while the regime introduced

measures to Germanise the country by force, and any kind of activity was

viewed with suspicion by the secret police, Hungary nevertheless embarked

upon the road of economic development in the period following its defeat.

Agricultural output increased and certain branches of industry, such as

milling, coal-mining, metallurgy and processing, showed signs of development,

and Hungary

began exporting a considerable quantity of goods.

Meanwhile, international conflicts were

increasingly undermining the status of the Hapsburg Empire, whose position

was aggravated by internal resistance. The Hapsburg armies had been defeated

by the forces of the Italian risorgimento, supported by France,

and it was soon apparent that the Empire was without the economic resources

to wage a protracted war. Francis Joseph laid the blame for the debacle on

his government, and in the autumn of 1859, he compelled Alexander Bach to

resign. The dynasty began to seek some sort of a compromise with the

Hungarian ruling class. A long political struggle which lasted for eight

years began, in the course of which it was either the Hungarian public which

was dissatisfied with the rights being offered to them by the various

"diplomas" and "patents" issued by the Hapsburgs, or it

was the dynasty which considered the Hungarian demands too excessive.

Finally, external and internal changes created the conditions suitable for

compromise. The Hapsburg Empire was further weakened by defeat at the hands

of the Prussians at the battle of Königgrätz, while the Hungarians, faced

with serious economic difficulties, hoped that a compromise would lead to

loans, economic development, and the provision of posts in the 1848

government administration. It was under these circumstances that the

Compromise of 1867 was reached, mainly through the efforts of Ferenc Deák,

who had been a minister in the 1848 government and was the representative

politician of the lesser nobility.

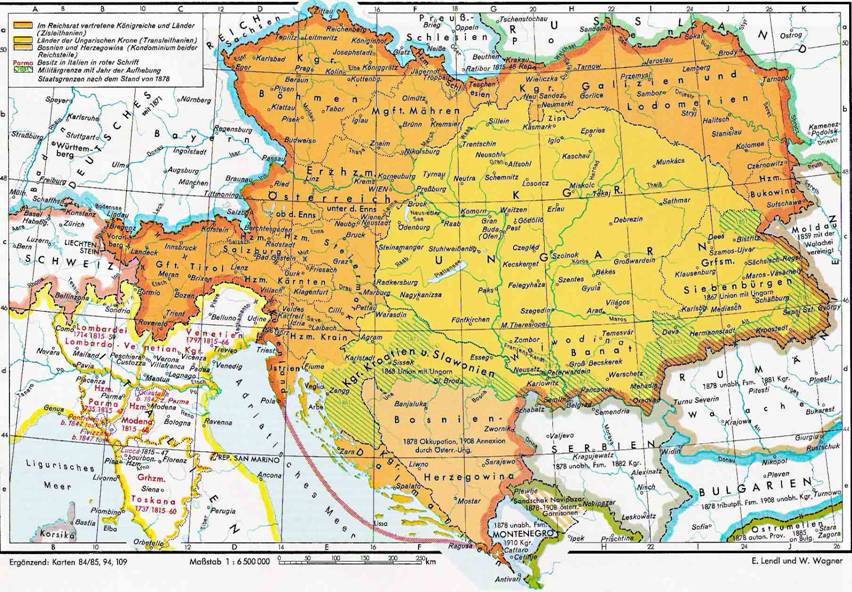

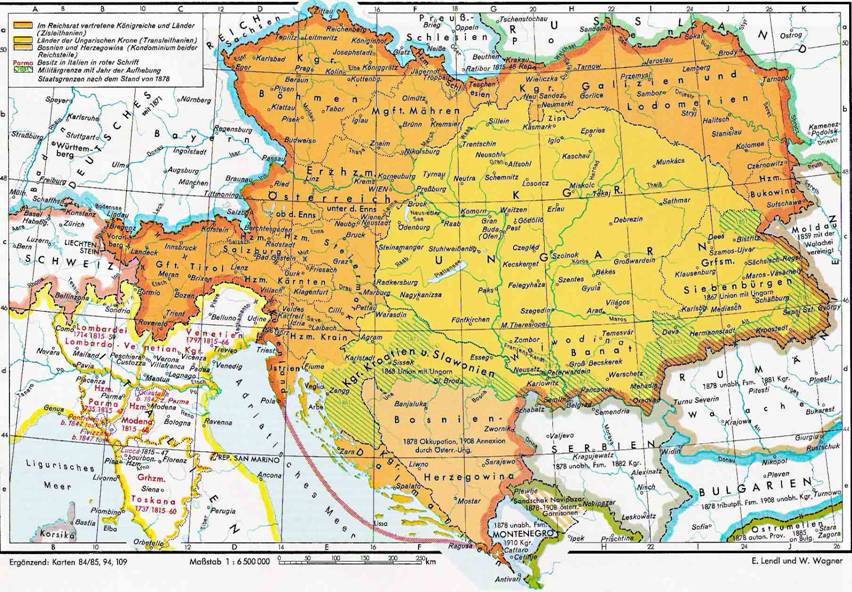

Click on the map

for better resolution

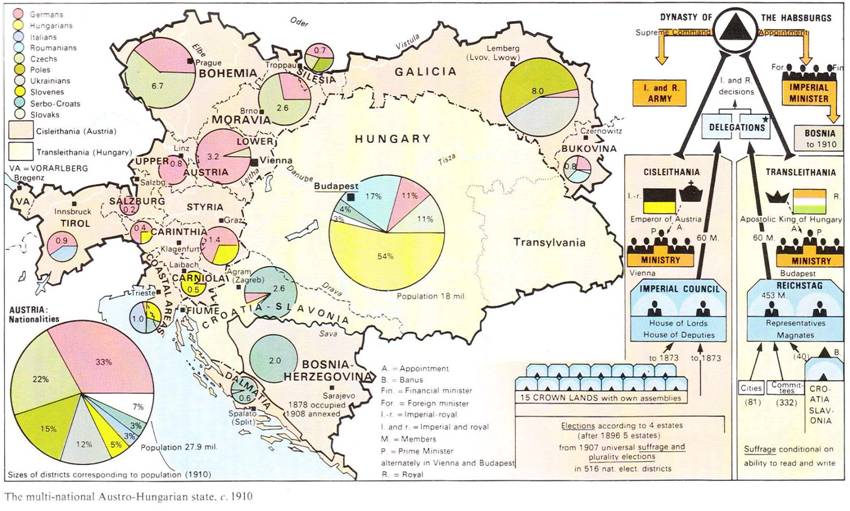

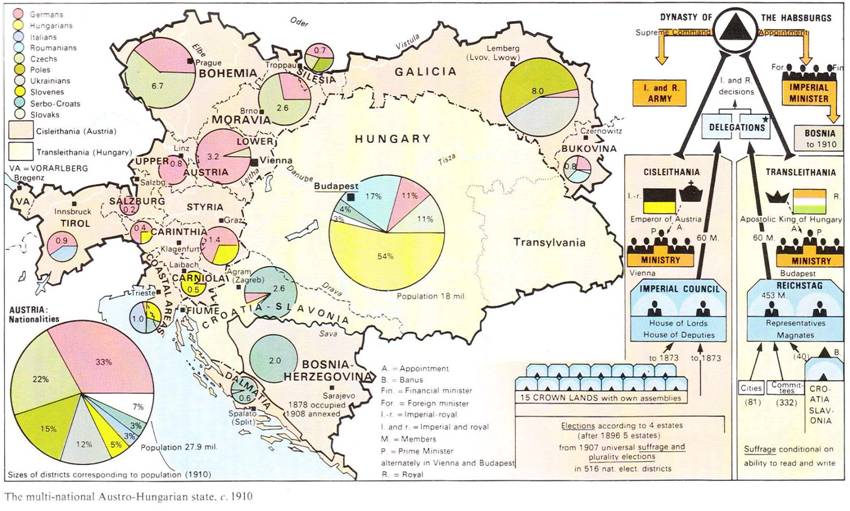

The Compromise reorganised the Hapsburg Empire

on a dualist basis. Within the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, both the Austrian

empire and the Hungarian kingdom became independent states with separate

legislative bodies and governments responsible to their legislatures. The

link between them was further assured by the common affairs of the

Austro-Hungarian Monarchy: defence, foreign affairs and the finances related

to these. Francis Joseph, who had been uncrowned up till then, was crowned

King of Hungary in the summer of 1867. According to the accounts from

contemporary records, it must have been a splendid occasion. The ceremony

took place in the rapidly developing community of Buda-Pest which already had

a population numbering around half a million. (Six years later, the towns of

Pest, Óbuda and Buda merged, giving birth to Budapest.) From each county in Hungary, a

sack of earth was brought to "Coronation Hill", onto the top of

which Francis Joseph galloped on horseback, wearing the Holy Crown and a

coronation robe, and carrying a sword to make the traditional slashes to the

four winds, signifying his intention to defend his country from any kind of

attack, from wherever it might originate. It is a scene that yearns for the

painter's brush, and in fact, it was soon rendered immortal by

chromolitography and appeared on the walls of schoolrooms, bank offices, and

middle class homes.

Source: The Penguin Atlas of World

History, Vol. 2, 1974. p. 78

The policy of appeasing the dynasty had a great

many supporters, but an even greater number of people hung the portrait of

"our father Kossuth" in their homes, and brooded in front of it

with nostalgia; for Kossuth, even in exile, had continued to support the

platform of independence and had condemned the Compromise. This dichotomy was

the essential feature of the internal political life of Hungary during the last decades

of the nineteenth century. In manifested itself in the struggle between the

ruling party, which supported the Compromise, and the opposition parties,

which adhered to the principles of 1848. It was a struggle interspersed with

many spectacular events, such as the sudden conversion of Kálmán Tisza, who,

discarding his programme of independence, formed a new government and

remained in power for three decades.

All these events occurred during a period of

economic growth, and with the promotion of industrial development, there was

a massive migration to the towns. A railway network was constructed in this

period, the main lines of which met at Budapest,

directing the interregional traffic of distant parts of the country to the

capital. This contributed to the development of Budapest as a centre of transport, and also

enhanced its commerce and industry. Budapest

developed at an astonishing speed, and in the course of a few decades, became

one of the great capitals of Europe.

Important new industrial firms, such as engineering works, textile and

leather factories were founded, and signs of development began to appear in

mining and in the metallurgical industries. The regulation of rivers and the

resulting cessation of the flood peril expanded the amount of arable land.

The modernisation of farming became feasible, and the output increased. The high point of the era

following the Compromise was marked by the celebrations of the onethousandth

anniversary of the Magyar Conquest of Hungary. However, behind the glossy

exterior and a basically unfounded optimism, a number of serious problems had

been tormenting the country for some time. Lacking capital, the owners of

small and medium-sized estates could not keep up with modern development, and

consequently went bankrupt. The number of farm labourers reached four

million, and thousands of landless peasants were forced to emigrate. The

discontent felt by the working masses and the national minorities contributed

to the further deepening of internal contradictions. The growth and expansion

of the working-class movement was marked by a series of strikes and

demonstrations which the government attempted to crush on several bloody

occasions. While the Monarchy drifted towards war, resistance to the imminent

conflict strengthened among the masses.

Hungary in the First World War. The Years 1918-19

Following the assassination of Archduke Francis

Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, at Sarajevo

on June 28, 1914, most politicians and military commanders of the Monarchy

favoured war against Serbia.

Count István Tisza, the Hungarian Prime Minister, was at first opposed to the

idea of declaring war. He considered the timing inopportunate and the

proposed annexation of Serbia

undesirable, as it would have increased Slav population of the Monarchy and

weakened the Hungarian ruling classes. He was, however, persuaded by Austrian

pressure to dispatch the unacceptable ultimatum to Serbia, it was worded thus

provoking a war. Posters bearing the signature of Francis Joseph appeared on

the streets of Budapest

declaring the war: "I have considered everything, I have thought over

everything...;" The Hungarian soldiers joined their regiments singing

and carrying bouquets. The troops were sent off at the stations by elegantly

dressed ladies to the sound of band music. It seemed as though the glittering

image of the millennial celebrations was turning into a new, even falser

illusion.

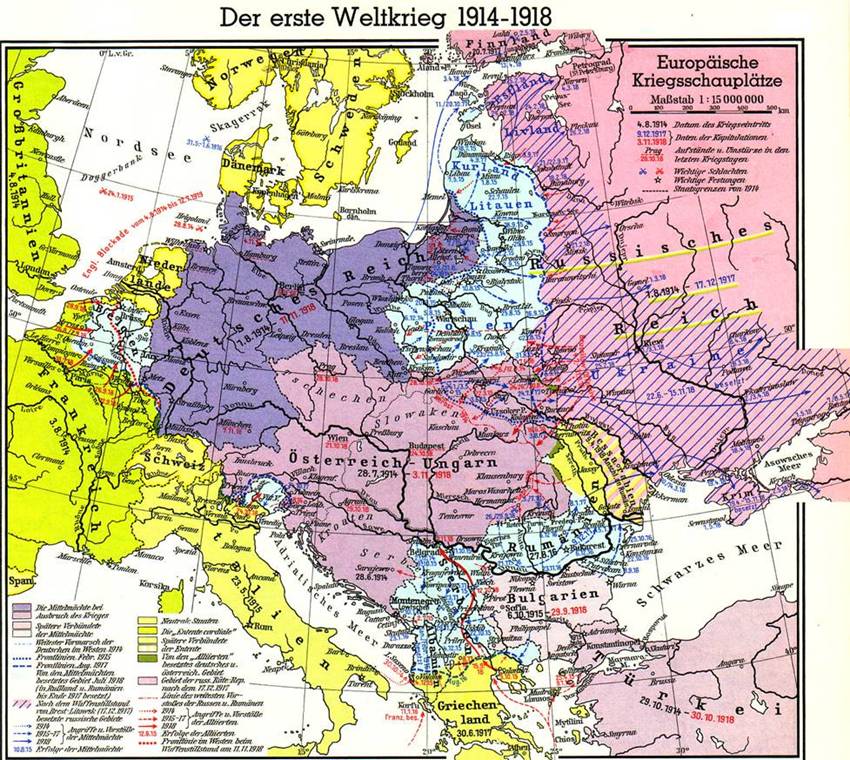

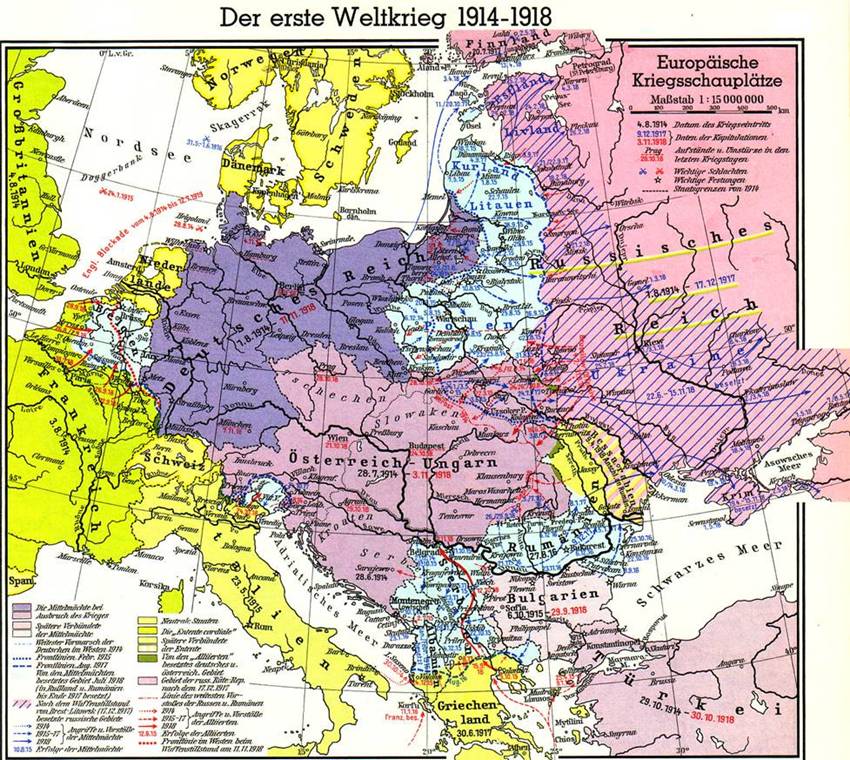

However, the enthusiasm was short-lived. Hungary was aligned with the Central Powers,

but events soon disproved the vainglorious prophecy of Kaiser William II that

the Germans would be in Paris

by the time "the leaves fall from the trees". The fighting

gradually developed into trench warfare with heavy loss of life on both

sides. In the first three years, Austro-Hungary lost three million men, and a

million of these were Hungarian.

The country was short of food, inflation was on

the rise, and wages lagged far behind the rapidly changing prices, while those

dealing in paper-soled boots and inedible rations reaped handsome profits.

Dissatisfaction was everywhere. Since 1915, Count Mihály Károlyi, the leader

of the political opposition, had been demanding a break with the Germans and

a separate peace. Following the death of Francis Joseph, the new king,

Charles IV (1916-1918), attempted to conclude that separate peace. He

proposed a series of liberal reforms and concessions to the national

minorities, but his attempts failed in 1917.

Source: Westemanns Atlas zur Weltgeschichte, Berlin,

1953

Click on the map

for better resolution

The 1917 February revolution in Russia had a great impact in Hungary; a wave of antiwar

strikes swept over the country. New left-wing trends made themselves felt

within the working-class movement, including the left-wing opposition within

the Social Democratic Party, which strongly attacked the opportunism of party

leadership. The revolutionary socialist group of university students, the Galilei Circle,

started organizing anti-militarist resistance in alliance with the trade

union workers. The effect of the revolution in Russia and the peace edict was

even more striking. Tension mounted rapidly in the country, which the

government was unable to do anything about. Strikes and demonstrations

engulfed the nation, and the revolutionary movement spread to the fronts. At

the same time, movements among the national minorities for self-determination

and independence took on increased vigour. By the summer of 1918, the fate of

the Monarchy was sealed. Even before its capitulation on November 3, 1918, a

National Council had already come into existence. Headed by Count Mihály Károlyi,

it demanded a separate peace, Hungarian independence, the recognition of the

right of self-determination for the national minorities, land reform, and

universal suffrage. On October 31, 1918, the masses, wearing asters on their

caps, marched through the streets of Budapest

and occupied the strategic points in the capital. Archduke Joseph, named homo

regius by the king, appointed Károlyi Prime Minister. On November 16,

1918, Hungary

was proclaimed a republic.

Károlyi, a liberal politician, whom the so

called "Michaelmas Revolution" brought to power as head of

republic, was opposed to the war and sympathetic to the Entente Powers. He

tried to alleviate the plight of the peasants and divided up his huge estates

among them. Despite this, he was soon overwhelmed by the territorial demands

and armed invasion of the Entente. On March 21, a communist regime took over

under Béla Kun. The hastily conceived measures of the communists -

nationalization of all the lands and taking most of the economy into state control

- met with resistance. Meanwhile the Red Army collapsed and the Romanian

forces marched into Budapest.

On August 1, 1919, the short-lived first communist regime of Hungary

was overthrown.

© Zoltán Halász

English translation by Zsuzsa Béres

Translation revised by J.E. Sollosy

Bibliographic data:

Title: Hungary

(4th edition)

Authors: Zoltán Halász / András Balla (photo) / Zsuzsa Béres

(translation)

Published by Corvina, in 1998

159 pages

ISBN: 963-13-4129-1, 963-13-4727-3

|

|