|

|

On August 26, 1541, fifteen years after the

Battle of Mohács, Buda

Castle became the scene

of unusual events. Ferdinand of Habsburg had been besieging the castle since

April, but without success: the Hungarian defence forces continually repelled

his attacks. On this day, Sultan Suleiman also appeared under the walls of

the castle. Roggendorf, the Hapsburg commander, clashed with the Turks, but

shortly afterwards, made a quick retreat. At this point, the sultan invited

John Sigismund, the one-year-old prince, to his camp, together with the

Hungarian leaders. While the festivities were in progress in the camp,

janissaries pretending to be peaceful visitors infiltrated Buda Castle

and once inside, disarmed the Hungarian guard. The Sultan declared that a

Turkish garrison would be stationed in Buda, and that the region of the Great

Plain would become part of the Ottoman Empire.

The child John Sigismund and his power was limited to Transylvania and the

region beyond the Tisza.

The events leading up to the Sultan's coup

reached back fifteen years when, following their victory at Mohács the Turks

did not occupy Hungary.

Instead, looting and pillaging wherever they passed and seizing large number

of people as slaves, they withdrew from the country. This provided an

opportunity for organizing the resources of the country against another

Turkish offensive. However, this did not happen. The lesser nobility elected

the wealthiest landowner in the country, János Zápolyai, as king (1526-1564)

on the throne at their counter-Diet. The dual election was followed by

internal warfare. After the mercenary army of Ferdinand of Hapsburg drove

Zápolyai out of the country, he sought th Sultan's support in regaining his

throne. In 1529 Suleiman II personally led his forces into Hungary to help Zápolyai. On the

site of the battle of Mohács, Zápolyai formally planted the vassal's kiss on

the Sultan's hand. From this point on, Hungary became a battleground.

The Turks viewed Hungary

as the springboard for their attack on Vienna,

and the Hapsburgs, for their part, attempted to maintain at least the

northern and western parts of the country under their influence. In this way,

Hungary became the locale

for a great power struggle, in which both sides strove for decisive power in Europe.

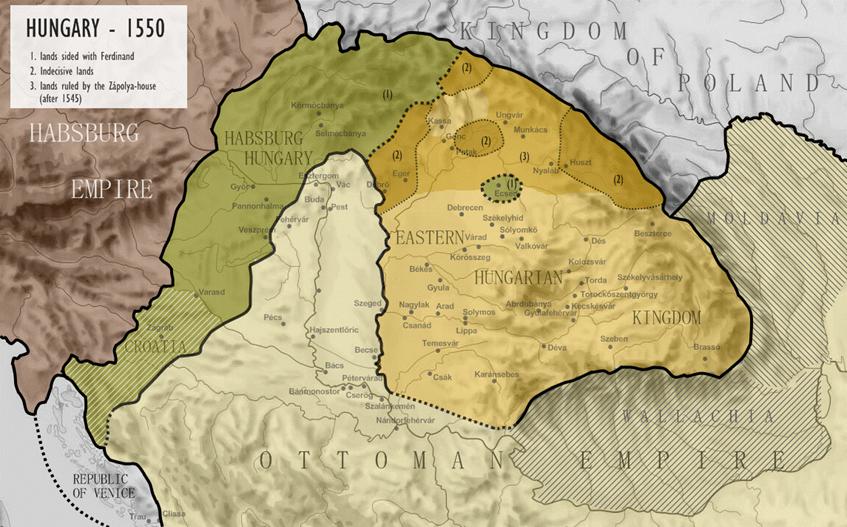

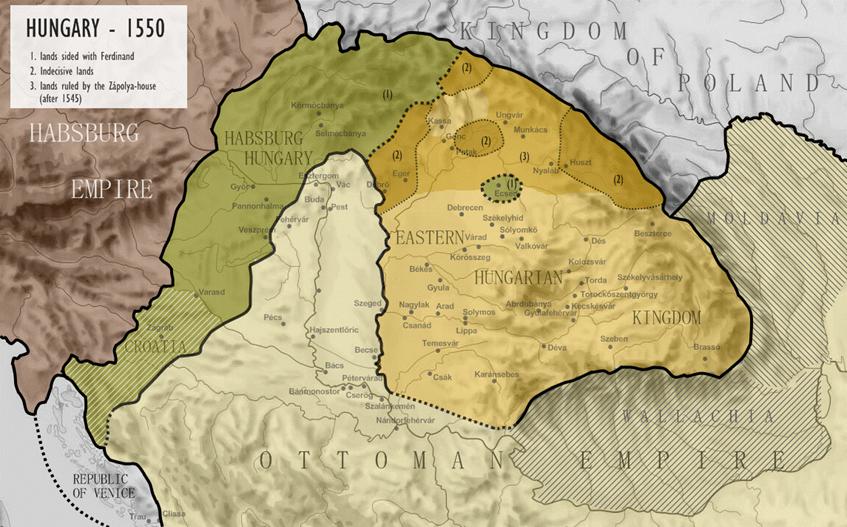

After the Turkish occupation of Buda in 1541,

the central and most fertile part of the country, the region of the Great

Plain, became part of the great Ottoman Empire

which streched over three continents. The supreme ruler of the entire

Hungarian territory was the begler bey of Buda, who, having the title

of pasha, was directly responsible to the Sultan. The Ottoman system

of taxation inflicted a heavy burden on the Hungarian serfs, and the law

restricted their freedom of movement. The "heathen" were not

allowed to build stone houses and could not repair their damaged homes

without permission. On the other hand, the Turks left the population to

practice the religion in peace. When war broke out, the Ottoman army again

spoiled, destroyed and plundered the country. At such times, Hungary became a veritable slave market; Asian

slave traders travelled as far as Buda and transported thousands of slaves to

the interior of the Ottoman Empire. The

resulting sense of uncertainty forced the population to take refuge in the

larger settlements, a movement which led to the depopulation and desolation

of hundreds of villages.

Click on the map

for better resolution

Click on the map

for better resolution

After the battle of Mohács, the western and

northern areas of Hungary

came under the rule of Ferdinand of Hapsburg as the Kingdom of Hungary.

Charles V left the government of the eastern part of his Empire to his

brother Ferdinand, who exerted all his energies in an attempt to unite Austria, Bohemia

and Hungary

under one centralized government. His Council of War strengthened the front

defences which ran through the heart of Hungary, and by the second half

of the sixteenth century, a network of frontier fortresses had been created.

For over a century this network remained the frontier between the

Ottoman-occupied part of Hungary

and part of the country under Hapsburg rule. Consequently, the area along the

line of border fortresses became the scene of continual clashes between the

defenders and the Turkish raiders.

The eastern region of the divided country, Transylvania, fell under the rule of Zápolyai's son,

John Sigismund. Following his death, prince István Báthori (1571-1586), who

had achieved a certain degree of independence from the Hapsburg and Ottoman

Empires, came into power. Báthori imposed a strong centralized rule. He also

recognized the value of heyducks, herdsmen who had banded together into

lawless fighters and marauders in the troubled times of war, and began to

organize them. He also made it possible for the lower classes of the Székelys

living as serfs to make their way upwards through military service.

Báthori planned his foreign policy on a

Central-European axis, bases upon an anti-Hapsburg,

Transylvanian-Polish-French alliance. He put himself forward as a candidate

for the empty throne of Poland,

and, with the help of the Polish lesser nobility, was crowned in 1576,

consequently becoming one of the great Polish kings.

The degree of slaughter and devastation in Hungary

at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was equalled only by

the Thirty Years' War shortly afterwards. The Fifteen Years' War began in

hope of driving the Ottoman forces out of the country. However, it only

resulted in defeat and further gains for the Turks. Moreover, the imperial

Hapsburg mercenaries plundered and devastated the northern part of the

country and Transylvania, which had been

relatively peaceful until that time. They aggravated the situation by their

aggressive methods and murderous ways, confiscating estates and persecuting

the Protestants under Belgioso and Basta, the imperial mercenary commanders.

The Hapsburgs also employed the method of show trials for treason in order to

confiscate the estates of the landowners, and used force to take away the

Protestant churches.

General embitterment and discontent led to the

first Hungarian uprising against the Hapsburgs in 1604. The beginning and

success of the uprising are linked with the name of István Bocskai, a

landowner in Eastern Hungary. He negotiated

a secret agreement with the Ottomans, recruited the heyducks under his flag,

and after a series of victories over the Hapsburgs, became prince of Transylvania in 1605. Bocskai refused the title of king

offered to him by the Sultan, his only objective being to bring peace to the

country caught between the two great rival powers, the Hapsburg Empire and

the Ottoman Empire. As a result of his

steadfast efforts, the Treaty of Vienna was signed in 1606. In this treaty

the Emperor undertook to bring the unsuccessful war against the Turks to an immediate

end, to return the expropriated estates to their Hungarian owners, to

guarantee the freedom of religion, and to station only Hungarian soldiers in

the country. Following the Treaty of Vienna, the Emperor signed a treaty with

the Turks as well, which concluded the Fifteen Years' War. Although the

provisions of the Treaty of Vienna were not fully enforced (in the years

immediately following the signing of the Treaty of Vienna, a

Counter-Reformation movement led by Péter Pázmány, the brilliant Archbishop

of Esztergom, emerged, reconverting the majority of the Protestant magnates,

and their serfs, to Catholicism), Transylvania nevertheless continued to be

the main bastion in the struggle for independence from the Hapsburgs. Prince

Gábor Bethlen (1613-1629), under whose reign Transylvania

enjoyed a golden age of economic and cultural development, took up arms

against the Hapsburgs several times during the Thirty Years' War to help the

Protestant forces.

Why did the Hungarian fight against the

Hapsburgs when it was the Turks who held a substantial part of their country

under occupation? The answer to this question lies in the Hapsburgs' refusal

to take as strong a stand against the Turks as their power and resources

would have permitted in their use of Hungary as a buffer-state, and in

their compromise solutions - negotiated both openly and in secret - which

seriously conflicted with fundamental Hungarian interests. A flagrant example

was the tragic fate of Miklós Zrínyi, the Hungarian writer, statesman and

military leader. Zrínyi, who was the bán (viceroy) of Croatia

and a landowner in the south, strove for the expulsion of the Turks both in

his writings and on the battlefield, and his extremely fast and victorious

campaign proved that his policy of saving the nation was realistic and

feasible. Nevertheless, the imperial general Montecuccoli, and not Zrínyi,

was appointed commander-in-chief of the army against the Ottoman forces. The

attitude of this "procrastinating general" is summed up by his often-quoted

saying, "Three things are required for war: money, money, and

money." Following the victory which Montecuccoli finally managed to

secure, the imperial court signed a treaty which was tantamount to defeat in

return for certain Ottoman trade concessions to Austrian trading capital.

Zrínyi died amidst mysterious circumstances while hunting, and even today the

suspicion remains that he was murdered. In any case, it is a historical fact

that the nobles who led the anti-Hapsburg movement were captured and executed

after Zrínyi's death, and their estates were confiscated. The Hapsburgs

utilized this event to abolish Hungarian self-government and to undertake a

campaign of repression against the Hungarian Protestants. The country was

overrun by mercenaries who plundered at will.

In the second half of the seventeenth century,

armed clashes became increasingly frequent between Hapsburg mercenaries and

the ever growing number of outlaws. These men, known as Kuruc, were forced to

leave their homes as a result of the tyranny of the imperial authorities. At

the same time, the embittered serfs deeply sympathized with them. The early

Kuruc attacks on the Imperial troops ended in failure. Resistance

strengthened when a young landowner, Count Imre Thököly, took over the

leadership of their uprising in 1678, and having organized a strong army,

successfully occupied the northeastern parts of the country. Thököly was

consequently made prince of Upper Hungary,

and a short-lived Upper Hungarian principality was established. Hungary

thus became divided into four parts.

Because of its ware with France, the Hapsburg government

had few forces available to deal with the Kuruc threat and was forced to make

concessions to the Hungarian barons. The Diet convened in 1681,

re-established baronial government, took measures to end the outrages of the

German soldiers, announced an amnesty, and made concessions with regard to

freedom and religion. As the result of these concessions, the majority of the

Hungarian ruling class abandoned Thököly and decided to reach an agreement

with the Hapsburgs. Thököly and a faction of the Kuruc fighters nonetheless

were determined to continue their resistance.

Thököly's position was greatly weakened in the

eyes of the public, because his strategy was based on Ottoman support despite

tha changing balance of power in Europe. In

light of the events at the end of the century, it became increasingly clear

that the time for the expulsion of the Turks from Hungary had come. After the grand

vizier Kara Mustapha's unsuccessful siege of Vienna in 1683 by an army of two hundred

thousand, Emperor Leopold I, realizing the seriousness of the situation,

finally ceased his passsive strategy towards the Turks. Under continued

encouragement from Pope Innocent XI, the "Holy League" of Austria, Poland

and Venice

was established for the struggle against the Turks. A peace treaty, valid for

twenty years, was signed by Austria

and France,

and the allied forces - in which a great number of Hungarian soldiers also

fought - began their campaign. In the summer of 1686, after fierce fighting,

they captured Buda, and the following year they reoccupied Transylvania.

Under the leadership of Charles of Lotharingia and later of Eugene of Savoy,

they drove the Turks from Hungary.

The final victory of the war, the battle of Zenta in 1697, was followed by

the Treaty of Karlovitz [Karlóca] in 1699, which, with the exception of a

small region, freed all of Hungary

from Turkish occupation.

The question now poses itself, how was it

possible that barely four years after the long-awaited liberation from a

century and a half of Turkish repression, there followed an all-out war of

independence against the Hapsburgs? Why did the people of this impoverished

country rise in arms and fight for eight long years against the superior

forces of the powerful Hapsburg Empire? The answer is not simple, for the

problems are manifold. But one reason for the revolt was that the Hapsburgs

violated the interests of the Hungarian landowners when they did not return

their estates in the areas formerly under Turkish control. Instead, they were

distributed among the Austrian aristocracy, officers of the Imperial Army,

and high-ranking court officials. The peasants and serfs were severely

affected by the state tax and the so-called portio imposed on them. In

addition they were forced to provide quarters and food for the imperial

troops. Townspeople also suffered under the burden of ruthless taxation. The

Hungarian troops who formerly manned the frontier fortresses were returned to

serfdom. The ruined peasants and the thousands of soldiers condemned to new

serfdom fled the villages and took refuge as outlaws and bandits in the

forests and mountains. The world of the wandering and fleeing poor was once

more revived.

In the northern section of the discontented

country, a few serfs and a handful of the former officers of the Thököly

movement began to organize another anti-Hapsburg movement. Accepting their call

to assume command, one of the greatest leaders of the independence movements

in Europe, Prince Ferenc Rákóczi II, enters

the stage of Hungarian history. Rákóczi's father had been Prince of

Transylvania, and his stepfather was Imre Thököly, the leader of the Kuruc

uprising. His mother, Ilona Zrínyi, was herself a descendant of military

leaders who fought and defended their country against the Turks; she made a

heroic defence of the fortress of Munkács against the siege of the Hapsburg

army during the final days of the Thököly uprising. Afterwards, she followed

her husband into exile.

The young Ferenc Rákóczi, the wealthiest

landowner in the country, had learnt the oppressive methods of the Viennese

court through personal experience. The Hapsburgs separated him from his

family in his youth and deprived him of his freedom, but Rákóczi escaped from

the prison at Wiener Neustadt and managed to reach Poland before his threatened

trial for treason. In 1703, accepting the offer of leadership from his

supporters, Rákóczi returned to Hungary, where great masses of

peasants assembled under his banner. In a short time, he had an army of

seventy thousand which soon swelled to one hundred thousand. With this army

at his disposal, he quickly occupied the greater part of the country. By this

time the war of independence - which began as a popular uprising - was joined

by large numbers of the nobility. In 1705 the Diet elected Rákóczi as the

ruling prince of the confederation of insurgent Hungarian nobles, announced

the dethronement of the Hapsburgs, and in 1707 proclaimed the independence of

Hungary.

On Ádám Mányoki's contemporary portrait,

Rákóczi looks at the world with a natural and spontaneous expression. His

heavy dark hair falls to his shoulders from the plumed fur cap that he is

wearing. His finely cut and slightly sensuous lips show a man who is fond of

life, but the pondering and searching look of his brownish grey eyes reveal a

thinker of profound insight. Rákóczi was a highly educated and open-minded

man. He conducted his correspondence with his unreliable ally, Louis XIV, in

French. During the bitter years of exile, he wrote his Confessions -

philosophical and anguished pieces of writing - in fine classical Latin. The

manifestoes and decrees which he issued in Hungarian, dictating and revising

them himself, were the shining examples of faultless and concise Hungarian

prose. He was an excellent organizer whose concerns ranged from providing for

the needs of the army to solving increasingly serious economic problems. His

foreign policy was broad-minded, yet realistic. He established relations with

France and Poland,

and sought Russian support.

Yet in the end, the Kuruc war of independence

was defeated. After the victory of the Hapsburg forces at Höchstadt, the opportunity

was lost for a joint French-Hungarian offensive, and Hapsburg military

pressure mounted. The internal contradictions in Hungary continued, and discontent

grew among the peasants because they had been waiting in vain for the measure

that would free the serfs. The nobility abandoned the struggle that had

entailed heavy material sacrifices and deserted to the Hapsburg camp in

growing numbers. There was a shortage of money and the soldiers began to

leave their units. And while Rákóczi was in Russia at the court of Peter the

Great to seek aid, Sándor Károlyi, the commander-in-chief of the Kuruc

forces, capitulated (1711). Rákóczi spent the rest of his life in exile,

first in France, then in Turkey.

Following the end of the Kuruc war of

independence, the first decades of the eighteenth century marked a period of

accommodation and compromise between the Hapsburg administrators and the

Hungarian barons. The repopulation of areas devastated under Ottoman rule was

rapidly taking place. Masses of serfs flowed from Northern

Hungary - which had not been occupied - to the depopulated

southern areas, and they in turn were replaced by Slovak, Southern Slav and

German settlers. Due to large-scale immigration, the population doubled in

seventy years, reaching over eight million. At the same time, however, the

number of the non-Hungarian population was greater that the Hungarian.

The idyllic state of affairs between the

dynasty and the Hungarian nobility began to deteriorate around the middle of

the century. At first the Hungarian part of the compromise involved the

maintenance of the county system, and nobles who pledged allegiance to the

Hapsburgs were allowed to retain their estates. The authority of the baron-controlled

Hungarian Diet was also maintained. In return, the Hungarian ruling class

again recognized the Hapsburg dynasty as the monarchs of Hungary. In 1723 Charles III

(1711-1740) induced the Hungarian barons to accept the Pragmatic Sanction,

which recognized the rights of inheritance of the female offspring of the

Hapsburg dynasty and the indivisibility of the Hapsburg Empire.

The Hungarian estates enthusiastically

supported Maria Theresa (1740-1780). Perhaps the most blatant example of

their enthusiasm is the well-known engraving of the young queen holding her

baby son (later King Joseph II) as the members of the nobility zealously

declare that they will sacrifice their "life and blood" to save the

throne from the Prussian rival. Naturally, they shouted in Latin and,

according to contemporary gossip, they added very quietly: "sed

avenam non", that is, they would be willing to sacrifice their

blood, but unwilling to supply oats to feed the army horses. Naturally,

reluctance was not confined to the oats, and in the course of time, the

conflict deepened between the Hungarian nobility, who insisted on the

retention of their feudal prerogatives - i.e., the outdated serf system and

exemption from taxation - and the Hapsburg administration. When Joseph II

(1780-1790), the most interesting and impressive personality of all the

Hapsburgs, tried to implement reforms based on the ideals of enlightened

absolutism, the resistance of the nobility grew stronger. The decrees easing

the oppression of the serfs were only successfully enforced after the

repression of a peasant uprising in Transylvania

which frightened landowners sufficiently for them to tolerate the

implementation of these measures. In the end, Joseph II was enforced to

cancel nearly all of his reforms on his death-bed.

A positive feature of the resistance against

the policies of Joseph II was the political programme designed to safeguard

the Hungarian language against Germanisation. Consequently, Hungarian

literature was given a new impetus. In the final decade of the century, under

the reign of Francis I (1792-1835) who considered that his principal task was

"to put the brakes on the demon of revolution," there emerged a

section of the lesser nobility and the intelligentsia which followed the events

in France

with active interest. It was from their ranks that a small group of very high

intellectual calibre was formed whose main political objective, besides the

independence of the country, was its transformation to a bourgeois society.

Their leader was the lawyer József Hajnóczy, and the group included the poet

János Batsányi, the writer Ferenc Kazinczy, and the economist Gergely

Berzeviczky. When Ignác Martinovics took over leadership in 1794, the group

was transformed into a revolutionary Jacobin organization. The organization

was shortlived, and the membership must have still been only a few hundred

when the imperial police arrested the leaders, who were executed in Buda in

1795.

© Zoltán Halász

English translation by Zsuzsa Béres

Translation revised by J.E. Sollosy

Bibliographic data:

Title: Hungary

(4th edition)

Authors: Zoltán Halász / András Balla (photo) / Zsuzsa Béres

(translation)

Published by Corvina, in 1998

159 pages

ISBN: 963-13-4129-1, 963-13-4727-3

|

|