|

|

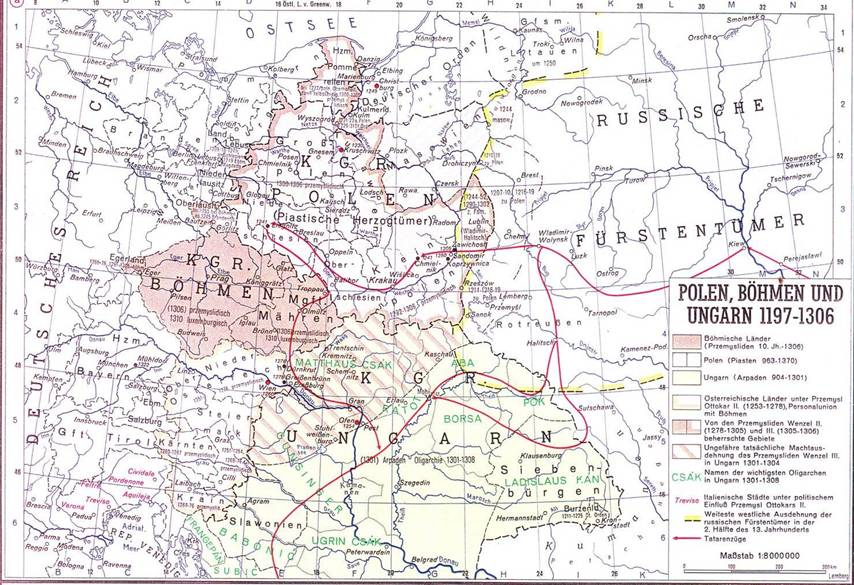

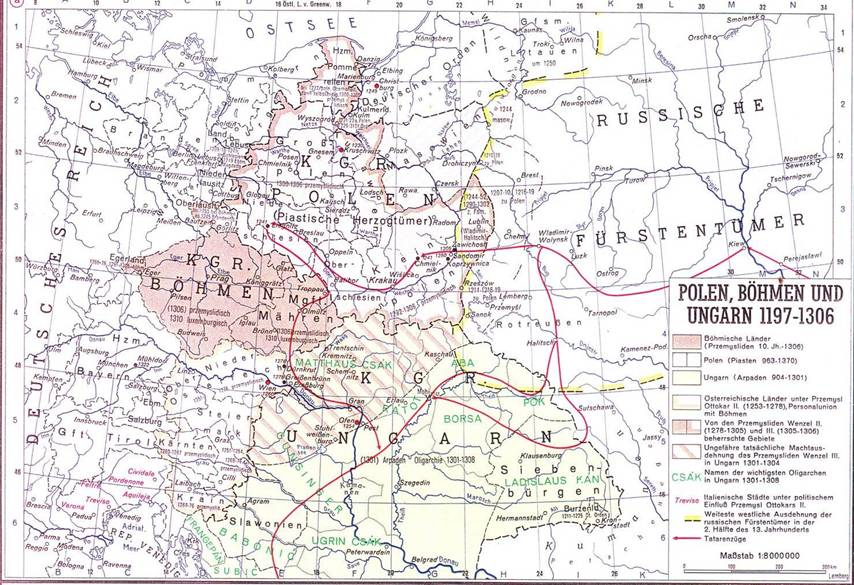

It is the spring of 1241. The first sentries of

dreaded Mongol forces appear at the north and north-eastern passes of the

Carpathians. They are riding tiny, long-haired horses, and are wearing

iron-plated armoury made of leather straps. After provoking and harassing the

defending forces with feigned attacks, Batu Khan's forces concentrate their

power and irrupt into Hungary

through the Verecke pass, the route used by the Magyars at the time of the

Conquest. The commander of the defending forces, the Palatine of Hungary,

flees wounded from the scene of the battle. He just escapes death. The

assailants first swoop down upon the northern part of the country, looting

and massacring as the proceed forward. Later they come to grips with the main

Magyar forces, led by Béla IV, in the valley of the river Sajó. During the

night, the Tartars secretly cross the river and set fire to the Magyar camp.

The greatest part of the besieged Magyar army, suffering an attack from the

rear, is annihilated. The survivors flee towards the west and south. Soon the

northern part of the country is completely under the assailants grip. When

winter sets in, the Mongol forces cross the ice of the frozen Danube with

ease and the whole of Transdanubia, the land west of Danube,

is at their mercy. Only a few fortresses protected by stone walls hold out

and, in fact, succeed in repelling the attack. The rest of the region up to

its western border is occupied by the Mongols. From the western border, the

Austrian Prince Friedrich mounts an attack, not against the Tartars, but

against the surviving Magyar towns, and occupies Sopron and, for a short time, Győr. He

imprisons Béla IV, who had fled to his court, and releases him only for a

heavy ransom. The Tartars pursue the king, who is trying to organize

resistance, and search for him everywhere. They follow his trail to Zagreb and Dalmatia. He

finally takes refuge in Trogir. To quote a German chronicler: "After

three hundred years, Hungaria was no more."

Source: Putzgers,

F.W., Historischer Schul-Atlas, Bielefeld,

1929

Click on the map

for better resolution

In fact, it did appear as though Hungary

had been annihilated by the Mongol invasion. However, internal dynastic

conflicts erupted within the Mongol Empire, resulting in the withdrawal of the

Mongol hordes from the country in the summer of 1242. Hungaria

survived the apparently fatal devastation. Its population decimated, its

towns reduced to ashes, and its villages razed to dust, the country survived.

Béla IV began the reconstruction of the country, building castles and

fortified towns to forestall the threat of another Mongol invasion. He

invited German, Walloon and Italian settlers, and by granting them special

privileges, promoted urban development. The king, who was called "the second

founder of the state", planned the construction of Buda

Castle, raised the settlements of

Buda and Pest to the rank of towns, and founded the Dominican convent on Margaret Island. On this island, which lies

between Buda and Pest, his daughter Margaret

- who was later canonized - lived as a nun. The Mongol invasion proved to be

a turning point in more ways than one. The country's survival was proof of

the strength of the people. However, the manner of reconstruction - though

necessary under the circumstances - became the source of further internal

strife and feudal anarchy. The king, fearing another Mongol invasion,

encouraged feudal lords to build strongholds. These new strongholds, however,

became a basis of a power in which the role of the king became more and more

insignificant. At the same time, a growing number of lesser nobles were

forced into positions of dependence by the greater lords as soldiers in their

private armies. The stormy and glorious reign of Béla IV (1235-1270) was

followed be renewed struggles over succession and battles between opposing

factions. Later, with the death of king Andrew III, the male line of the

House of Árpád became extinct, and thus, the right of inheritance through the

female line became a possibility.

In the early 1970s, the fragment of a

Trecento-style statue was unearthed during archaeological excavations in one

of the courtyards of Buda

Castle. Further

excavations uncovered over forty statues and fragments, a veritable graveyard

of statues. In all probability, they had adorned the Friss (New) Palace of Sigismund of Luxemburg, later Holy

Roman Emperor.

The statues of ladies, knights, court

musicians, servants and guardsmen mark not only the turn of the fourteenth

and fifteenth centuries, but also the beginning of a new age. Dressed in

full-length gowns, richly gathered cloaks, pointed shoes and daring hats,

they are an unexpected reminder of a flourishing, almost decadent Hungarian Trecento,

whose mere existence was no more than a conjecture before the miraculous

appearance of the archaeological foundings at Buda Castle.

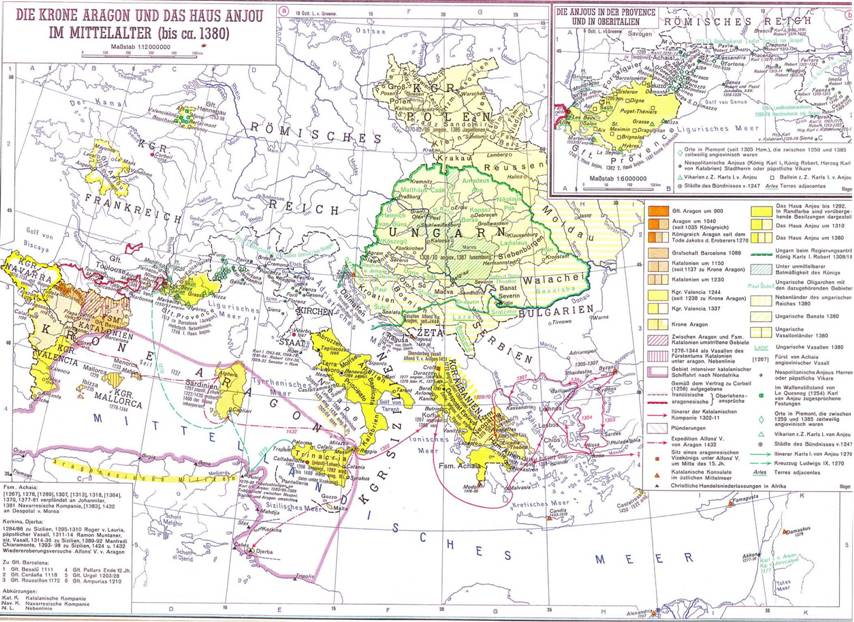

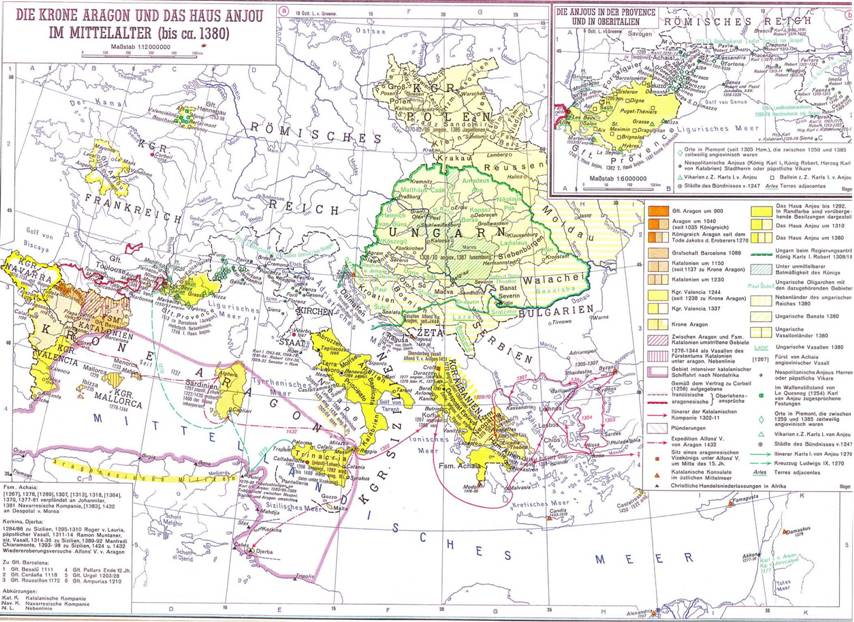

Charles Robert, the descendant of the Naples

branch of the Angevin House and through his grandmother of the House of Árpád,

became king after the death of Andrew III, the last monarch of the House of

Árpád. At the height of the feudal anarchy, the barons, whose power was far

greater than that of the king, fought battles and made alliances. However, by

gradually overcoming the power of the barons, breaking the resistance of the

renegade towns and putting an end to chaos, Charles Robert, who grew up among

the modern financial and trading life of Naples and Milan, brought prosperity

to feudal Hungary. Knights, soldiers, businessmen and artists from Naples and other Italian

towns brought a new vitality. This is why the achievements of the Trecento

appeared relatively early in Hungary as compared to other European countries,

and why they formed a new kind of unity, merging local tradition and Gothic

art in the works of succeeding generations.

Source: Putzgers, F.W., Historischer Schul-Atlas, Bielefeld, 1929

Click on the map for better resolution

Charles Robert was a realist in economic

matters. He had no plans for conquest and held that his two greatest

achievements were the introduction of a new Hungarian currency, the gold forint

modelled on the Florentine design, and the meeting he arranged between

himself and the Polish and Bohemian kings at his castle in Visegrád, which

gave birth to important decisions concerning the development of foreign trade

between their countries. His son, Louis I (1342-1382), came to be known as

Louis the Great because of his dynastic and expansionist policies. His forces

advanced as far as Naples, Treviso, and the Bulgarian Viddin, and he

later acquired the Polish throne. Since he died without male issue, the

throne was assumed by Sigismund of Luxemburg, Louis the Great's son-in-law.

This fullblooded and gluttonous king, who lived for the pursuit of love and

adventure and wasted enormous amounts of money, had one great aim - winning

the crown of the Holy Roman Empire, which he

acquired in 1433. Sigismund made extensive use of the resources of Hungary

to further his aims abroad, and loans linked to mortgages on the royal

estates played a growing part in financing his ventures. This policy reached

such proportions that by the middle of the fifteenth century, the estates of

the great barons made up more than half the territory of Hungary.

Central power was finally weakened to such an extent that only Sigismund's

alliance with the powerful Czillei-Garai League could ensure his position on

the throne. Meanwhile, the expansionist Ottoman Empire was posing a direct

threat to the country, and after the resounding defeat at Nicopolis in 1396,

all Sigismund could manage was feeble resistance against repeated Turkish attacks

upon fortresses in the southern region of Hungary.

Sigismund's turbulent and stormy reign,

however, also had its positive aspects; towns grew and flourished, and the

multilingual and educated royal court exerted a favourable influence on the

development of the arts and culture in general. Large-scale building schemes

provided ample and long term work for the artists, for example, the building

of the Friss (New) Castle in Buda, the castles of Visegrád, Tata and

Várpalota. In Sigismund's court there were patrons such as Pipo Spano, a

descendant of the Scolari family of Florence,

who invited Manetto Ammanatini and Masolino da Pannicale to Hungary. Artistic frescoes were

painted, beautifully illuminated codices were produced by the royal workshop,

panel painting flourished, and so did sculpture.

When the noon-day bells chime from the church

steeples of Europe, they serve as a reminder of a historic event that took

place in 1456 under the medieval walls of Belgrade

[Nándorfehérvár], the capital of present-day Yugoslavia. The protagonists were

Murad, the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and

János Hunyadi, the outstanding military leader of the age. Belgrade was besieged from all sides by 300

thousand Turkish soldiers. The sultan had planned to capture the great

southern stronghold and from there push into Hungary, and the west. Belgrade's defence was

led by Mihály Szilágyi, Hunyadi's brother-in-law. The fate of the fortress

was critically important for the future of Europe.

Pope Calixtus III called for a crusade and sent Giovanni Capistrano, a

Franciscan friar, later canonized, and an outstanding orator, to Hungary.

He was to help Hunyadi recruit soldiers to relieve the forces at the castle.

Before the siege of the fortress began, Pope

Calixtus III issued a bull calling for prayers for the defenders of the

fortress and ordering the ringing of the bells at noon. The peoples of the

southern region flocked to Hunyadi's army, and troops arrived from Poland, Germany,

Vienna and Bohemia, composed primarily of artisans,

students and peasants. There was a shortage of food and ammunition at the

fortress, so their position appeared hopeless. However, at the last moment,

Hunyadi arrived with his relief forces. His boats broke through the blockade

set up on the Danube by the Turkish ships

and succeeded in establishing communication with the beleaguered garrison.

Hunyadi organized the defence of the stronghold and the counterattacked,

destroying the Turkish forces. The Turkish army left Belgrade defeated and having suffered

severe losses, including the loss of its fleet. Hunyadi's victory at Belgrade was the most severe defeat the conquering

sultans had ever suffered, and for another half century, it saved Hungary

from similar attacks by the Ottoman power.

János Hunyadi's (c. 1407/9-1456) career was an

astonishing one. The youth who was descended from a family of the lesser

nobility was first a page, and later the leader a mercenary unit. In the

service of the Italian princes, including the Sforzas, he became acquainted

with the techniques of organizing a modern mercenary army and learned the

importance of the foot soldier and the artillery. His remarkable gifts as a

military commander and statesman were responsible for his meteoric rise, in

the course of which he became one of the greatest landowners in the country,

a baron, Ban of Szörény, Voivode of Transylvania and the commander of the

campaigns againts the Turks, as well as governor of the country.

The day after his victory at Belgrade, Hunyadi died a victim of the

plague which devastated the war-stricken country. It seemed for a time that

with his death the power of the Hunyadis had also come to an end. As a result

of political intrigue, his older son Ladislas was executed by the king, and

the younger son, Matthias, was taken as a hostage with him to Prague. However, in the

year of the Belgrade

victory, the neurotic king, Ladislas V, died suddenly in the Bohemian

capital. A large-scale movement launched by the lesser nobility, townsmen,

and of course, the Hunyadi faction, forced the barons participating in the

Diet held at Buda

Castle to elect

fifteen-year-old Matthias as the ruler of the country. According to the

chronicles, the resistance of the barons was broken by fifteen thousand armed

nobles, who marched over the ice of the frozen Danube

to the walls of the Castle. This action was so successfully accomplished,

that after long weeks of procrastination, the decision favouring Matthias

took only a few hours to make.

There are few figures in Hungarian history

surrounded by as many legends, anecdotes and entertaining stories, as that of

King Matthias. His image as the defender of the common people against the

arrogant barons is just as much a part of Hungarian historical folklore as

"Mátyás deák" (Student Matthias). In this characterization,

Matthias roams the country in disguise, unveils injustice, rewards virtue,

and conquers the hearts of young girls and beautiful women, who never even

suspect that the clever, goodlooking traveller they hold in their arms is the

king himself.

Obviously, tales and fables known to many

peoples have exerted influence over Hungarian folklore (e.g., attributing the

deeds of Harun-al-Rashid, memorialized in The Thousand and One Nights,

and other legendary heroes to Matthias). It is also obvious, however, that

the historical memory of a nation, as well as its nostalgia, is manifested in

the tales about Matthias; for the reign of King Matthias between 1458 and

1490 was the golden age of medieval Hungary. With astonishing strength and

political wisdom, the adolescent elected to the throne of the country broke

the resistance of the various baronial factions opposing him and, with a

series of measures, built up a centralized monarchy based on the absolute

power of the ruler. He created a highly disciplined mercenary army supplied

with modern weapons, and reformed the system of jurisdiction. This, together

with the creation of a stable centralized power and public security, provided

a solid basis for the development of industry and commerce. Matthias

encouraged the growth of towns and made Buda his royal residence, which

consequently became one of the most beautiful in Europe.

To the Gothic Friss (New) Palace in Buda Matthias added a new wing in the

Renaissance style which held his famous library, the Bibliotheca

Corviniana. The first printing press was established in Buda in 1473.

There was also an outburst of scientific activity. Hundreds of Hungarian

students made their way to the universities of Vienna,

Cracow, Padua

and Bologna, returning to Hungary to spread the influence

of the new learning. In Pozsony [now Bratislava]

the Academia Istropolitana was founded; at the court of Matthias,

Antonio Bonfini was writing his Rerum Hungaricarum Decades, and the

Italian humanist Galeotto Marzio, was also active there. Janus Pannonius, the

humanist poet famous throughout Europe,

worked in Pécs. Nor were architecture and the fine arts neglected. The royal palace of Buda,

the magnificent palace of Visegrád with its three hundred and fifty rooms and

the fortress castle

of Diósgyőr were all

embellished with works by Hungarian and Italian artists, including Benedetto

de Maiano, Verrocchio, Leonardo and others. A portrait of Matthias was

painted by Mantegna.

Matthias pursued a vigorous and active foreign

policy. In the early years of his reign he launched an offensive attack

against the Turks. Later, he conducted an expansionist foreign policy towards

Moravia and Silesia,

and finally, against Austria.

After occupying Vienna in 1489, he transferred

his royal residence there from Buda, and it was in Vienna that he died in 1490. At the time of

his sudden death, he left behind him a flourishing country which stood at the

forefront of European development.

A contradictory and ominous political figure at

the turn of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Tamás Bakócz had been, in

the course of his career, royal secretary and Bishop of Győr under King

Matthias's reign. Under the reign of Matthias's successor, Wladislas II, he

was royal chancellor, Archbishop of Esztergom, and later a cardinal. A master

of Machiavellian intrigue and a remarkable political strategist, trusted by Venice and mediator

between Milanese and Florentine bankers and Buda, he rose in the course of a

few decades from the son of a wheelmaking serf to the rank of the richest and

most powerful men in the country. In 1510, Bakócz set himself the greatest

objective of his life, the attainment of the vacant papal throne. He arrived

in Rome at the head of a magnificent

delegation, and for months he attempted to dazzle the Eternal City

with sumptuous festivities on which he spent enormous sums of money. As far

as the papal throne was concerned, his efforts remained fruitless, for the

conclave elected young Giovanni Medici as the head of the Church. However,

the new pope, Leo X, "consoled" Bakócz with a Bull which enabled

him to declare a crusade against the Turks. The status of the serfs had

deteriorated in the course of the preceding years due to increased

oppression, including restriction of their freedom of movement. Bakócz and a

section of the landowners were convinced that the serfs would march to the

faraway battlefields, and consequently, the tense internal situation would

become less dangerous. The majority of the barons and nobility, however,

opposed putting arms in the hands of the peasants. When men from all parts of

the country began to gather together for the holy crusade against the Turks,

many of the landowners used force to keep their serfs at home. They oppressed

the families of those who had gone, forcing them to accept the labour and

duties of those absent from home. The crusading force, formed as it was of

the dissatisfied masses, rapidly turned into an anti-feudal army. When Bakócz,

urged by the alarmed feudal lords and nobles, suspended the crusade, the

infuriated masses refused to obey his orders. György Dózsa, a Székely cavalry

officer who had already proven himself in battle against the Turks, led his

army to the Hungarian Great Plain where larger and larger groups of peasants

joined him, and the towns on the plains also sided with them. Realizing the

threat to their power, the barons and the lesser nobility temporarily set

aside their differences at this point, and the cavalry of the nobility

swooped down on the peasant army, which had laid siege to Temesvár [now Timisoara]. The peasant

forces suffered decisive defeat at the hands of the experienced and

well-armed nobility, and after the uprising had been finally crushed, ruthless

revenge was taken on the peasants. Dózsa was captured, seated on a red-hot

throne, crowned with a red-hot iron crown, and burned alive. Thousands of

peasants were executed. The Diet was convened in the autumn of 1514 proceeded

to pass a law depriving the serfs of all freedom of movement.

It was under these circumstances that the

decisive attack of the Turks took place. After occupying two of Hungary's

southern bastions, the Turkish Sultan Suleiman II (1496-1566) launched a

large-scale offensive with a well-equipped army of eighty thousand in the

summer of 1526. The Hungarian forces, led by Louis II, barely consisted of

twenty thousand men who were poorly armed in comparison to the Turkish army.

The decisive battle was fought at Mohács by the Danube

river and ended with the annihilation of the Hungarian army. Fifteen thousand

were killed in the battle, and the king himself died on the battlefield. This

event was one of the tragic turning points in Hungarian history, and its

efforts were felt for centuries to come. The territorial unity of medieval Hungary,

together with its independence, were lost.

© Zoltán Halász

English translation by Zsuzsa Béres

Translation revised by J.E. Sollosy

Bibliographic data:

Title: Hungary

(4th edition)

Authors: Zoltán Halász / András Balla (photo) / Zsuzsa Béres

(translation)

Published by Corvina, in 1998

159 pages

ISBN: 963-13-4129-1, 963-13-4727-3

|

|