|

|

No written sources on the early history of the Hungarian

people have come down to us. Consequently, the material for study must be

sought in the evidence of language, archaeology, ethnography and

anthropology. Comparative linguistics provides the main field of research for

what is known as Hungarian prehistory, for it demonstrates that the Hungarian

language, judging by its vocabulary and structural pecularies, belongs to the

Finno-Ugrian group of the Uralic languages, more precisely, to its Ugrian

branch. It has not been possible to determine whether the original home of

the Uralian prehistoric peoples was in Europe or Asia.

It is believed, however, that the common homeland of the Ob-Ugrians and the

ancient Hungarians (the Magyars) was along the central Volga.

The ancestors of the Hungarians were for the most part fishermen and hunters,

but is is probable that they were acquainted with animal husbandry, the

tanning of leather, pottery, and the carving of wood and bone.

In the middle of the first millennium B.C., the

ancestors of the Hungarians migrated from the lands they had shared in common

with the other Ugrian peoples and moved south. Here they came under the

influence of the Bulgar-Turkic pastoral tribes, with a resulting change in

their manner of life: their primary occupation as mounted nomads was

transformed into herding, and they lived in a tribal society. In the course

of their migrations, they came into contact with different nomadic empires

which formed with amazing speed on the steppes only to collapse later with

the same dramatic suddenness. In the middle of the fifth century B.C., the

ancestors of the Hungarian people joined the Onogur tribes of Bulgar-Turkic

origin and lived with them along the northern shore of the Black

Sea. For a time they were subject to the lax sovereignty of the Turkish Empire. Later a part of the Onogurs withdrew

themselves from the Khazar overlordship and migrated to the south to found

the Bulgarian homeland on the lower Danube.

Another group of the remaining Onogurs drifted towards the Volga,

while the rest formed a tribal alliance under Khazar overlordship. As time

went on, they began to use the name of the strongest tribe in the alliance -

the Megyer tribe - as a generic term for the whole group. This is the

origin of the name Magyar, and of Magyarország - the name for a

Hungarian and for Hungary

in their own language today. The world applied to them in foreign languages (Hungarus,

Hongrois, Hungarian, Ungar, etc.) derives from the term Onogur. Accounts

of the Magyar migration differ in different sources. All we know for sure is

that they were forced by the attack of the Pechegens to move west to the land

between the Don and the Dnieper. Fleeing

from this region after another sweeping offensive in or around 895-896, they

entered the Carpathian

Basin, familiar to them

from their earlier raiding expeditions. At the time of the Magyar Conquest,

the area was inhabited mostly by Slavic ethnic groups; and Great Moravia,

situated on the northern part of the Carpathian Basin,

had been in a state of disintegration since the death of Prince Svatopluk.

The military power of the Pannonian Slav principality in the west did not

represent notable strength. The rule of the Bulgars, extending over the Great

Plain and Transylvania, was not

consolidated. Under these circumstances, the Magyars were able to overrun the

whole area of the country without difficulty. The military leader of the

conquering tribes was Árpád, and after the founding of the state, his

descendants became the rulers of the country.

The land occupied by the conquering Magyars had

been inhabited since prehistoric times. According to the archaeological

evidences found at Vértesszőlős, the Carpathian Basin

had already been the dwelling place of prehistoric man half a million years

ago. In the caves of the Bükk

Mountains, for example,

the one hundred and fifty thousand-year-old tools of Paleolithic man have

been unearthed. Human settlement also existed in the Middle Paleolithic

period in the region along the middle section of the river Tisza,

and in the Neolithic period the people of the Körös culture, who used

polished stone tools, had already taken up farming. THe earliest known art

also originates from the people of the Tisza,

the Great Plain and later from the Bükk and Transdanubian cultures. During

the early Iron Age, Thracians settled east of the Tisza and Illyrians west of

the Danube. The latter erected enormous

earthwork as defence against the Scythians and later against the Celts, who

came from the west.

In the early years of our era, the Romans, who

had conquered the Celts, extended their rule to the region of the country

lying west of the Danube, which then became a province of the Roman Empire

under the name of Pannonia.

A century later the province of Dacia was formed in the region of Transylvania.

The four centuries of Roman rule created an advanced and flourishing

civilization and the founding of the majority of the present-day towns in

western Hungary

can be traced back to Roman antecedents. For example, both Sopron and Szombathely

(Scarbantia and Savaria), located near the Austro-Hungarian border, developed

into important settlements along the Amber Route which extended from the

Baltic countries to Italy; the predecessor of Pécs in southern Hungary was

the Roman town of Sopianae, and Aquincum, the Roman predecessor of today's

Budapest, was a large town along the river Danube with a waterwork system, a

sewage system, steam baths, markets, and two amphitheatres.

Source: Black, Jeremy (Ed.), Atlas of World History, London/New

York, 2000

Click on the map for better resolution

After four centuries of existence, Roman

civilization was swept away by the great migrations. For five hundred years

the Carpathian Basin had been already the "the

people's highway", with various tribes such as the Visigoths, the

Ostrogoths and the Lombards migrating across the area after sojourning for

various lengths of time. Later, the empire of the Huns came into being, the

military power that finally forced the withdrawal of the Roman legions. After

the fall of the great Hun and Avar nomadic empires, only the Western Slavic

and Southern Slavic people succeeded in establishing themselves in the Carpathian Basin.

The advanced economic and political conditions

of the Slavs, who had been settling in the area since the 6th and 7th centuries, exerted a significant influence over the

Magyars; in fact, several words related to agriculture and handicrafts are

expressed in the Hungarian language by words borrowed from the Slavic

peoples.

An outstanding representative of the remaining

works of Hungarian Romanesque art (astonishingly great in number despite all

later losses through destruction) is a haggard male head carved from red

marble. Naturally, we do not know the identity of the artist, and since we

can only surmise that it depicts King Stephen I, the first king of Hungary,

art historians refer to the statue as "the royal head from

Kalocsa", the town where it was uncovered. It is a portrait whose hard

features suggest formidable energy and resolve, and bear witness to great

wisdom and understanding. King Stephen was probably this kind of person. Against

formidable odds, he proposed and implemented fundamental changes in Hungary.

In the course of this transformation the nomadic Magyars, who had been living

within the framework of tribal organization, settled permanently in the area,

took up the occupations of agriculture and handicraft, and exchanged their

ancient pagan belief for Christianity. Later events proved the choice a

historic one.

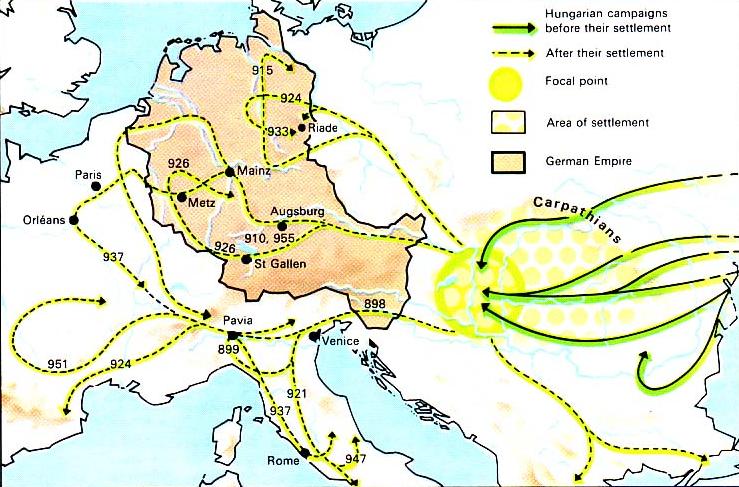

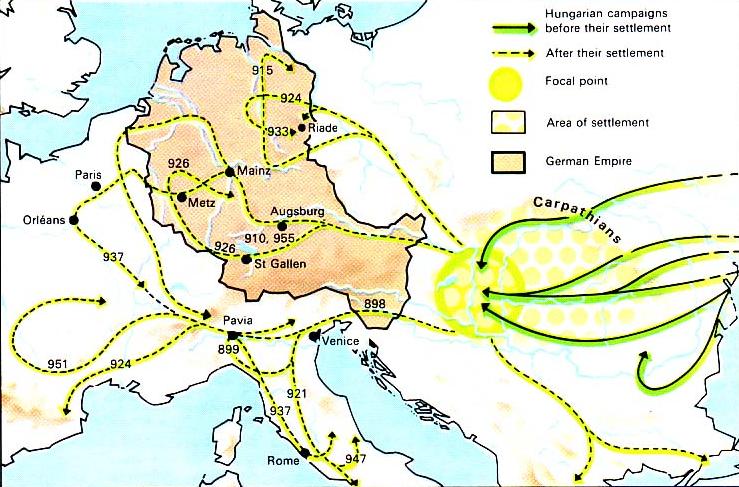

Source: The Penguin Atlas of World

History, Vol. 1, 1974. p. 168

The events that led up to it were as follows.

In the first half of the tenth century, during the decades the followed the

Conquest, raiding expeditions of Magyar mounted warriors subjected all Europe to a constant state of terror. In time, however,

they began to feel the effects of Western counter-strategy. When the Magyars

invaded Bavaria

in 955, the armoured cavalry of Otto the Great, Holy Roman Emperor, checked

their advance, and in the decisive battle at Lechfeld it annihilated the

Magyar assailants. Although the Magyars launched further attacks on Byzantium following this

devastating defeat, it became clear that they had arrived at a decisive

historic cross-road. Two alternatives confronted them: either they settle

down, form a state and adjust themselves to the people of Europe,

or else the same fate would befall them as that of the other nomadic peoples

who had been annihilated in previous centuries.

The first steps towards consolidation were

actually taken by King Stephen's father, Géza (972-997), the last Magyar

prince, who called in feudal knights and missionaries from the west to help

break the resistance of his people which was impending the spread of the new

faith and checking the transformation taking place within the country.

However, the great task of implementing the change to Christianity was

carried out by (Saint) Stephen I (997-1038) who defeated the forces of the

rebellious tribal aristocracy, was crowned with a crown received from the

Pope, and replaced the ancient tribal structure with the newly founded Hungarian State. The counties became the

organizational units of the state and were ruled by governors (comes)

appointed by the king. By rigorous measures, Stephen I forced those still

loyal to ancient pagan beliefs to convert to Christianity, organized eight

bishoprics and two archbishoprics, and decreed that every group of ten

villages should build a church. Since there were two to three thousand

villages in the country, this order resulted in a greatly increased demand

for construction work, coupled with the demand for ceremonial robes, as well

as metal and goldsmith's objects for the churches. Furthermore, thanks to the

work of craftsmen invited from abroad, Hungarian goldsmiths, metallurgists

and stonemasons, the Magyar art of the Conquest gradually blended into the

Romanesque style, which was just spreading throughout Europe

at that time. This style became so deeply rooted in Hungary, that for a long time to

come, even small village churches were built in this manner. In the course of

his long reign, the most important political objectives developed by Stephen

I were the introduction and implementation of internal reforms and the

preservation of the country's independence.

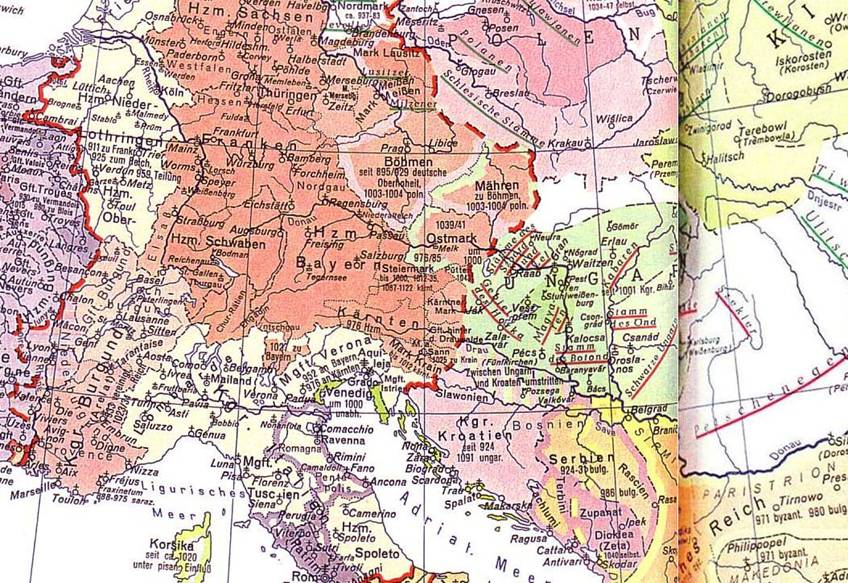

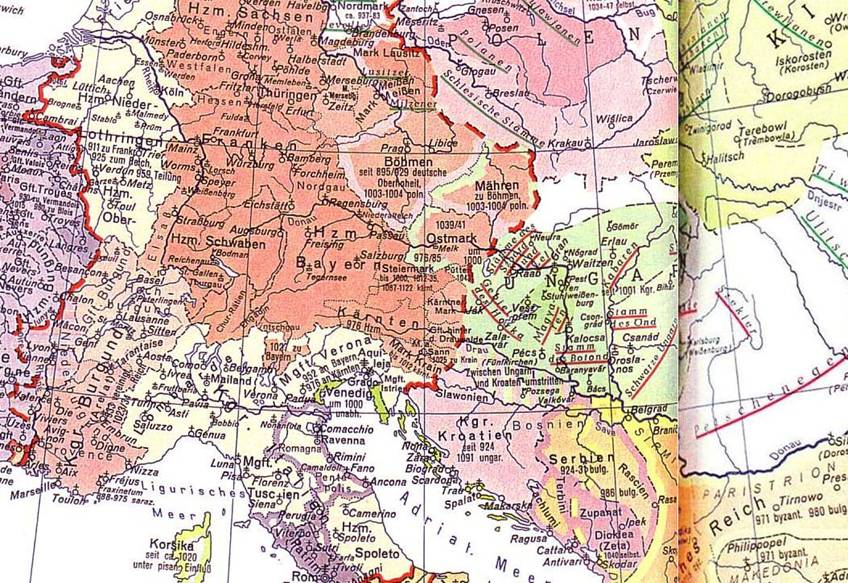

Source: Putzgers, F.W., Historischer Schul-Atlas, Bielefeld, 1929

Click on the map for better resolution

These same political objectives were passed on

to his successors. He himself fought successfully against Holy Roman Emperor

King Conrad II, frustrating his plans of conquest. Among his successors was

King (Saint) Ladislas I (1077-1095), who increased the territory of the

country, and supported the Pope in the investiture wars against the Holy

Roman Emperor. At the end of the twelfth century, King Béla III - educated

during his stay as a hostage at the court of Emperor Manuel and almost

succeeding him on the Byzantine throne - put an end to the interference of

Byzantium with some clever and form political maneuvering.

© Zoltán Halász

English translation by Zsuzsa Béres

Translation revised by J.E. Sollosy

Bibliographic data:

Title: Hungary

(4th edition)

Authors: Zoltán Halász / András Balla (photo) / Zsuzsa Béres

(translation)

Published by Corvina, in 1998

159 pages

ISBN: 963-13-4129-1, 963-13-4727-3

|

|