|

|

HETMAN PETRO SAHAIDACHNYI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ROLE

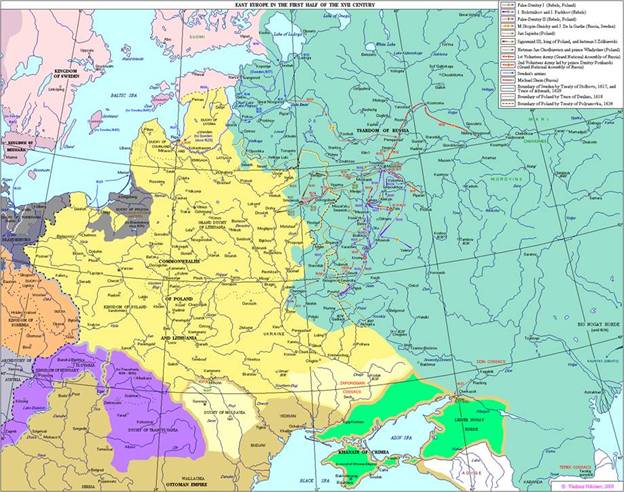

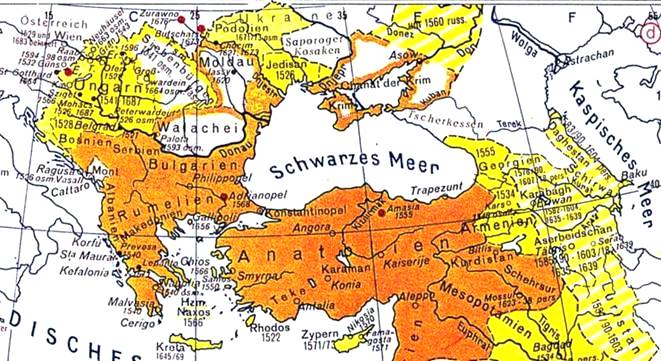

OF THE COSSACKS Paul Robert Magocsi Excerpts from the book History of Ukraine, Toronto / 1996 Map: Putzgers, F.W., Historischer Schul-Atlas, Bielefeld, 1929 |

||||||||||

|

|

The political interaction among the

king, the Polish and Rus' magnates and gentry, the gentrified registered

Cossacks, and the Cossacks of Zaporozhia began to play itself out with increasing

complexity after 1572, when the last Jagiellonian ruler died and the monarch

was henceforth elected by the Diet. Polish kings were becoming more and more

dependent on the whims of the magnates and gentry. Only those two factions of

the nobility could, through the Diet, authorize the necŽessary funds or

supply military forces to sustain Poland's foreign ventures. But most often

they were reluctant to do so, especially when it seemed to them that a

particular king, whether for dynastic or for economic reasons, was too eager

to enter into war with Muscovy, or Sweden, or Moldavia. Faced with such

internal political opposition, Poland's elected kings saw in the Cossacks a

ready-made force that could be used to further their own foreign policy and

military goals without their having to depend on the cooperation of the noble

estates. This intent is what gave rise to the policy of registration, whereby

Poland's kings would grant or restore Cossack privileges in return for

military service. For their part, the Polish and polonized Rus' magnates and

gentry opposed these direct relaŽtions between king and Cossacks, not to

mention the continuing existence of a group that remained outside their

control. The Rus' magnates in Ukraine, howŽever, favored the existence of the

registered Cossacks as long as they remained in their service and not that of

the king. The

international role of the Cossacks The vast majority of the

unregistered Cossacks, in Zaporozhia, continued their policy of providing short-term

service to Poland's kings and seeking alliances with foreign powers. During

the last decade of the sixteenth century, they accepted an invitation from

the Habsburg emperor of the Holy Roman Empire to join in a crusade against

the infidel Ottomans. They took this occasion to raid and loot at will the

Ottoman provinces of Walachia and Moldavia. Then, in the second decŽade of

the seventeenth century, they fought on the side of Poland's king Zygmunt III

during his frequent invasions of Muscovy. It was also during these decades

that they built a large naval fleet, which, under the leadership of their

daring hetman Petro Sahaidachnyi, raided Ottoman cities along the northern as

well as southern shores of the Black Sea. In the tradition of the Varangian Rus'

almost 800 years before, Sahaidachnyi's Cossacks even plundered the outskirts

of the impregnate Ottoman capital of Istanbul.

Hetman Petro

Sahaidachnyi and his seal The Ottomans held the Poles to blame

for the exploits of their unruly Cossack subjects, and not surprisingly,

Polish-Ottoman relations deteriorated as a resit In the spring of 1620, a combined

Turkish-Tatar army defeated a Polish force ac the Battle of Cecora/Tsetsora

Fields, near the Moldavian town of Iassi. The road to Poland was now open.

The Ottomans made further military preparations, and the following spring, in

1621, they advanced with an army of over 100,000. In desperaŽtion, the Poles

called on the services of Hetman Sahaidachnyi, and it was his forcr of 40,000

Cossacks (drawn from Zaporozhia as well as from the ranks of the reenŽtered)

that made possible a Polish victory over the Turks at the Battle of Khotyn m

northern Moldavia, near the border with Podolia. Click on the maps

for better resolution Thus, during the first half of the

seventeenth century, a seemingly unbreakable cycle arose within the

Crimean-Ottoman-Polish triangle that surrounded Cossack Ukraine. The

Zaporozhian Cossacks would raid the Crimea and the Ottoman Empire. In

response, the Ottoman Empire would threaten and sometimes cam out military

invasions against Poland. The Polish government would demand thai the

Zaporozhians cease their anti-Ottoman and anti-Crimean raids, and to back up

its demands would periodically send punitive expeditions to intervene in

ZapoŽrozhian affairs. The Zaporozhians would rebel against this interference,

and wan against Poland would result, with sometimes one side, sometimes the

other winŽning. In the end, nothing decisive ever occurred, and the cycle was

repeated. The Polish-Cossack conflicts before

1648, however limited in scope to the borŽder regions near Zaporozhia,

witnessed much of the brutality that accompanies any civil conflict. Polish

frontier aristocrats like the hetmans Stanislaw Zolkiewski Stanislaw

Koniecpolski, and Stanislaw and Mikolaj Potocki seemed to take special

delight in trying to put down what they considered the Cossack rabble, and

their victories at the battles of Lubni (1596), Pereiaslav (1630), and

Kumeiky (1637) left a heritage of bitter hatred. For their part, the

Zaporozhian Cossacks had no illuŽsions about the Polish szlachta, and they

felt betrayed by their own registered CosŽsacks, who often sided with the

Poles. They felt especially betrayed by the king, who seemed ever ready to

call upon their services for campaigns in Moldavia, or Muscovy, or Sweden, or

against the Ottomans, but careless of living up to his promises of greater

privileges or payments. Because of the Polish system of government, however,

even if the kings were desirous of fulfilling their promises, they could

almost never effectively do so over the heads of the szlachta opposition.

Thus, the pre-1648 period left the Zaporozhian Cossacks with a deep-seated

hatred and distrust of the Poles, combined with an ingrained historical memorv

of their own courageous hetmans such as Dmytro Vyshnevets'kyi and Petro

SahaiŽdachnyi, their successful campaigns against the Crimean Tatars and

Ottoman Turks, and their ability to circumvent Polish aristocratic control

over their lives. It was on this era (the 1630s) that Nikolai Gogol', a

nineteenth-century Ukrainian author who wrote in Russian, based his famous

novel of Cossack revolt against Polish rule, TarasBul'ba (1835).

The role of the Cossacks in

Ukrainian life was not limited, however, to military raids and protection of

the frontier. Before long, they combined their love of freedom and autonomy

with a deep commitment to defend the Orthodox faith. The ideological link

between the Cossack struggle for autonomy and its defense of Orthodoxy was in

large part forged during the first two decades of the seventeenth century by

Iosyf Kurtsevych-Koriiatovych, the archimandrite of the Terekhtemyriv

Monastery (halfway between Kiev and Cherkasy) and Hetman Petro Sahaidachnyi.

A native of Galicia and probably of noble descent, Sahai- dachnyi was

educated at the Ostrih Academy, where he was imbued with an Orthodox spirit.

He then went to the sich, where the Zaporozhians elected him hetman. He not

only increased the commitment of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to the Orthodox

faith, but also led them in numerous victories against the Tatars and the

Turks, and - in the service of Poland - against the Muscovites. In return for

his loyalty to Poland, so crucial to the king on the eve of the 1621 Battle

of Khotyn against the Ottoman Turks, Sahaidachnyi included in his demands the

full restoration of the Orthodox hierarchy, most of whose eparchial sees had

been left vacant after the Union of Brest in 1596. Meanwhile, during the first two

decades of the seventeenth century Kiev itself was undergoing a revival which

was to make it once again the center of Rus'- Ukrainian culture. The

Monastery of the Caves (Pechers'ka Lavra), founded under Iaroslav the Wise

during the mid-eleventh century, was headed from 1599 to 1625 by another

native of Galicia, Ielysei Pletenets'kyi. While Sahaidachnyi was raising the

military and political prestige of the Cossacks, Pletenets'kyi was busily

engaged in creating a new basis for Orthodox cultural activity in Kiev. In

1615, he brought to the monastery a printing press from Striatyn, in Galicia,

and during its first fifteen years of operation (1616-1630) it produced forty

titles, more than any other press in the rest of Ukraine or Belarus. Among

the titles were works of literŽature, history, and religious polemic,

liturgical books, and texts for the growing number of schools. The last

category included Pamva Berynda's Leksykon slaveno- rosskii (Slaveno-Rusyn Lexicon,

1627), the first dictionary in the East Slavic world, which, together with

another contemporary work, published elsewhere, Meletii Smotryts'kyi's

Grammatika slavenskaia (Slavonic Grammar, 1619), established a standard for

the Church Slavonic language that was to be used in Ukraine for the next two

centuries |

|

|||||||||