|

|

THE COSSACK REVOLUTION AND THE COSSACK STATE (1648-1667) Paul Robert Magocsi Excerpts from the book ”History of Ukraine”, Toronto / 1996 |

|||||

|

|

Khmel'nyts'kyi and the Revolution of 1648 Bohdan Khmel'nyts'kyi is the central figure in Ukrainian history during the seventeenth century. Some have also considered him the most important leader in modern Ukrainian history. First of all, it was during his tenure of less than a decade as hetman (1648-1657) that the Cossacks, and with them half of Ukraine's territory, changed their allegiance from Poland to Muscovy. This proved to be the beginning of a process that was to result in the further acquisition by Muscovy of Ukrainian territory from Poland until the final disappearance of the Common¬wealth from the map of Europe at the end of the eighteenth century. Even more important for Ukrainian history was the fact that Khmel'nyts'kyi succeeded in bringing most Ukrainian lands under his control and in ruling the territory as if it were an independent state. His Cossack state consequently provided an inexhaust¬ible source of inspiration for future generations of Ukrainians, many of whom strove to restore what they considered to have been an independent Ukraine under Khmel'nyts'kyi.

Hetman Bohdan

Zinovii Khmel'nyts'kyi A pivotal figure in the history of ecistern

Europe during the seventeenth cen-tury, Bohdan Khmel'nyts'kyi has been viewed

in radically different ways. Not sur¬prisingly, traditional Polish

historiography considered Khmel'nyts'kyi the leader of a destructive uprising

that seriously undermined and eventually destroyed the Polish state, while

Russian historiography has viewed him as a leader who success¬fully led the

Orthodox 'Little Russians' into the fold of a united Russian state. Ukrainian

writers see Khmel'nyts'kyi as an outstanding leader who successfully restored

the idea of national independence that had lain dormant since Kievan times.

Although some Ukrainians may criticize him for his sociopolitical and

dip¬lomatic failures, especially his decision to submit to Muscovy, all agree

that his rule was a crucial turning point in Ukrainian historical

development. Jewish histo¬rians of eastern Europe view Khmel'nyts'kyi as the

instigator of the first genocidal catastrophe in the modern history of the

Jews. They point out that not only was the vibrant Jewish community in

Ukraine largely decimated, but this early 'holo¬caust' brought about the

inner-directed and mystic emphasis which marked the subsequent development of

eastern Europe's Ashkenazi Jews. Finally, Soviet Marxist writers, both

Russian and Ukrainian, tended to stress the popular revolu tionary aspect of

the Khmel'nyts'kyi years. Beginning in the 1930s, they placed the Cossack

leader into that small but politically significant pantheon of acceptable

pre-Soviet national heroes, especially because he was so instrumental in

setting out along a course which led to the 'reunification' of the brotherly

Ukrainian and Russian peoples. Thus, for some, Bohdan Khmel'nyts'kyi has been

a hero, either qualified or of the highest order, while by others he is seen

as a villain or even the devil incarnate. Who was this man, whose career is

still the subject of historical debate and contemporary political polemic? Khmel'nyts'kyi's

Early Career Bohdan Zinovii Khmel'nyts'kyi was born

about 1595. His actual birthplace has not been determined with certainty,

although many believe it was his father's estate ai Subotiv, near Chyhyryn,

not far from the Dnieper River and about forty-three miles (seventy

kilometers) south of the frontier town and Cossack center at Cher- kasy. The

boy's father, Mykhailo, was a registered Cossack of gentry origin, proba¬bly

from Belarus, who had served in Galicia (in the town of Zhovkva) on the staff

of the renowned early seventeenth-century Polish general Hetman Stanislaw

Zolkiewski. Subsequently, Mykhailo Khmel'nyts'kyi was invited by the district

starosta at Chyhyryn to serve in that town, where he soon became

viee-starosta and settled on an estate in nearby Subotiv, where his son

Bohdan was later born.

Hetman Stanislaw

Zolkiewski In the absence of an Orthodox school in the

relatively near city of Kiev (one was not opened there until 1615), Bohdan was

sent to a Jesuit school in Galicia (at Jaroslaw). After completing his

education, he served with his father and the Cossacks who fought with Hetman

Zolkiewski in the latter's abortive campaign against

the Turks in 1620. Both Zolkiewski and Mykhailo Khmel'nyts'kyi were killed at

the Battle of Cecora/Tsetsora Fields, near Ia§i in Moldavia, while the young

Bohdan was captured and sent to Constantinople. For the next two years, until

his mother forwarded enough money to redeem him, Bohdan studied Turk¬ish and

became thoroughly acquainted with Ottoman and Crimean politics as well as

with the difficulties faced by the Greek Orthodox church in the sultan's

capital. After his return home in 1622, Khmel'nyts'kyi served with the

registered Cossacks in his native region of Chyhyryn. At this time, during the 1620s and 1630s,

Khmel'nyts'kyi was known to favor an increase in the number of registered

Cossacks and an extension of their privi¬leges, and he was even suspected of

having participated in the Ostrianyn rebellion of 1638. Acting on that

suspicion, the Polish authorities demoted him from colo¬nel to captain

(sotnyk) and allowed him to serve in that position as head of the Chyhyryn

Cossacks. During the relatively peaceful years after 1638, Khmel'nyts'kyi

turned his attention to his estate near Chyhyryn, where he seemed destined to

spend the rest of his life as a typical registered Cossack whose primary

object was to enhance the status of his group so that it might eventually be

accepted as on a par with the nobility (gentry) in the rest of

Polish-Lithuanian society. But the steppe zone in which Khmel'nyts'kyi, like

his father before him, lived was under¬going rapid colonization and change,

and without the appropriate documents the Khmel'nyts'kyi family's claims to noble

status meant little to aggressive magnates who had a tradition of

appropriating lands from the gentry, whether or not they were of proven noble

status. Accordingly, Khmel'nyts'kyi's social status remained uncertain, and

he was forced to seek a modicum of security by rendering military service to

the king or by engaging in economic activity in an effort to increase at

least his material wealth. The uncertainty of his own position was

responsible for Khmel'nyts'kyi's favor¬ing changes on behalf of the registered

Cossacks, whose status had declined after the abortive revolts of 1637—1638.

He was particularly encouraged by King Wladyslaw IV's plans in 1646 to

organize a new crusade against the Ottomans. Courted for their military

potential, the Cossacks saw the king's plans as offering a way of improving

their own situation. In fact, Khmel'nyts'kyi was one of a four- member

Cossack delegation summoned to Warsaw in 1646 to negotiate with the king. So

much the greater, then, was his disappointment when the Polish nobility

succeeded in thwarting Wladyslaw's effort. Nonetheless, the Cossack

delegation supposedly received a secret charter from the king, which promised

to restore those privileges the Cossacks had enjoyed before 1638.

Khmel'nyts'kyi was anx-ious to obtain a copy of this charter for himself. The first few months of 1647 witnessed a

series of events that was to mark a turning point in Khmel'nyts'kyi's life.

Because of his importance as a historical figure, it is not surprising that

many legends have grown up around him, in partic¬ular about this crucial

period in his life. The more colorful of these legends, drawn from several

later sources, make up what the historian Mykhailo Hrushevs'kyi has dubbed

the 'Khmel'nyts'kyi affair.' The so-called affair refers to a 'struggle over

a woman' named Matrona/Helena, in whom Khmel'nyts'kyi - himself married with

a family — supposedly had an amorous interest. Eventually, Helena married

Khmel'nyts'kyi's local rival, the Polish vice-starosta of Chyhyryn, Daniel Czaplinski.

Just before Czaplinski won the hand of Helena, he raided Khmel'nyts'kyi's

estate at Subotiv, appropriated its movable property, and at some point

flogged the Cossack leader's son, who as a result of his injuries died soon

after. The violence and terror undoubtedly contributed to the untimely death

of Khmel'nyts'kyi's wife sometime in 1647. Khmel'nyts'kyi was a business rival of

Czaplinski's superior, the Chyhyryn star- osta, Aleksander Koniecpolski, who

for his part felt that the Cossack leader was encroaching on his liquor

monopoly. In response to the raid on his estate, Khmel'nyts'kyi sought

justice in the local court but was unsuccessful. He then journeyed to Warsaw

and put his case before the Polish Senate. There, too, he received no

satisfaction. While in the capital, he even turned to King Wladyslaw, who,

though he sympathized with Khmel'nyts'kyi, admitted that he was powerless to

intervene in Poland's szlachta-controlled legal and administrative system.

Wladislaw IV Vasa

(1595-1648). King of Poland,

Grand Duke of Lithuania Khmel'nyts'kyi's appeals to the royal court

and Senate in Warsaw served to alienate his enemies further, and after

returning home in late 1647 he was promptly arrested on Koniecpolski's

orders. Helped by friends, Khmel'nyts'kyi managed to escape and, with nowhere

else to turn, decided to follow in the foot¬steps of hundreds of discontented

registered Cossacks and lower gentry before him. In January 1648, he fled to

the Zaporozhian Sich and its Cossack host, who lived in relative safety

beyond the reach of the Polish authorities. These basic facts were later embellished by

several authors in such a way that the long-standing political, social, and

economic friction between Poles and Cos¬sacks was made to seem less important

as motivating Khmel'nyts'kyi's actions than his supposed rivalry with a minor

local Polish official over the love of a woman. In the end, however, it was

not a personal quarrel over 'Helena of the steppes,' but the ever-present

social, religious, and national tensions in seventeenth-century Ukraine that

set the stage for a series of events which would result in profound changes

in both Ukrainian and Polish society. The

Revolution of 1648 While the Zaporozhians may have been

subdued after the failure of the revolts in 1637 and 1638, they were not

eliminated. Now it seemed that the right leader - one who they heard was even

trusted by the king - had arrived in Zaporozhia in the person of Bohdan

Khmel'nyts'kyi. Khmel'nyts'kyi immediately set out to allay the traditional

attitude of suspicion on the part of the Zaporozhians toward the 'gentrified'

registered Cossacks, and before the end of January 1648 he was elected

hetman. The new hetman anticipated conflict with the Poles and, drawing on

his experience with the Ottoman world, concluded an alliance with the Crimean

Tatars. Although Poland's governing circles were divided on how to han¬dle

this new Cossack threat, the view of the supreme military commander, Crown

Hetman Mikolaj Potocki, prevailed. Joined by his son Stefan (stationed at the

Kodak fortress) and the army of another Polish commander, and confident in

their military superiority, Potocki undertook a preemptive attack against the

Zaporozhian Sich. But to their surprise the Polish forces were intercepted en

route and defeated by a joint Zaporozhian-Tatar army under Khmel'nyts'kyi at

the Battle of Zhovti Vody on 5-6 May. In the course of the battle, Stefan

Potocki was captured by the Tatars (he later died of his wounds), and the

registered Cos¬sacks on the Polish side deserted to Khmel'nyts'kyi. With this

expanded Cossack- Tatar force, Khmel'nyts'kyi was able to pursue the Poles

and defeat them in a second battle, at Korsun', on 15-16 May, in which both

Polish commanders were captured. To make matters worse for the Poles, King

Wladyslaw died on 16 May, the day of their defeat at Korsun'.

The Zaporozhian

Cossacks Upon hearing the news of the Cossack

victories, discontented elements throughout the Kiev palatinate were inspired

to revolt. Peasants drove out or killed their Polish landlords and Jewish

estate managers; Orthodox clergy called for vengeance against Roman Catholic

and Uniate priests; and townspeople plot¬ted against the wealthy urban

elements. Thus, by the summer of 1648, two of Poland's leading commanders had

been captured, its large eastern army had been defeated, its Ukrainian

peasant population was in revolt, and its king was dead. Moreover, Poland's

traditional enemies - the Zaporozhian Cossacks and the Tatars - were flushed

with victory and there seemed no defense against them. Undoubtedly, the

Ukrainian peasant masses and the vast majority of the unregis tered

Zaporozhian Cossacks were ready to rid themselves of Polish rule once and for

all. But was Bohdan Khmel'nyts'kyi ready? Khmel'nyts'kyi's way of life, like that of other

relatively comfortable registered Cossacks, was the way of life of an

aspiring country gentryman. While he had been personally wronged by local

rivals, his initial goal was simply to obtain justice. If justice could not

be obtained through legal channels, then a military victory against the

Polish army might force the authorities to act favorably on his behalf. Even

after Khmel'nys'kyi had defeated Poland's eastern army twice, it is likely

that he would have welcomed the possibility of remaining a subject of the

king of Poland if he had been assured of personal legal redress and the

restoration to his fellow registered Cossacks of the privileges they had

enjoyed before the abortive revolt of 1637-1638. It was too late to go back,

however, whether he wanted to do so or not. Khmel'nyts'kyi's actions,

motivated by personal resentment, set in motion a sequence of events over

which he did not have complete control. He had to ride the waves or be

submerged. At first, Khmel'nyts'kyi tried to resist

the Cossack-peasant uprising, which after doing away with the local Polish

nobility would, he surmised, probably turn on the Ruthenian gentry and

registered Cossacks as well. He hoped to find support among Poles for his

desire to control what he considered the excesses of the revolution. In June

1648, pretending not to know of the king's death, Khmel'nyts'kyi stopped his

army at Bila Tserkva, just southwest of Kiev, and sent an emissary to Warsaw

demanding that the traditional Cossack privileges be restored; that the

number of registered Cossacks be increased to 12,000; that the Cossacks be

paid for their services of the last five years; and that the Orthodox church

be treated justly, in particular by having the churches and monasteries still

held by the Uniates restored to it. In return, the hetman pledged his loyalty

to the king. The Polish Diet was overjoyed with

Khmel'nyts'kyi's modest demands and agreed to have them considered by the new

king, whom they were still in the proc¬ess of choosing. Khmel'nyts'kyi then returned

to his estate near Chyhyryn and in early 1649 even managed to marry

Matrona/Helena, after her short-lived mar¬riage to Czaplinski was annulled.

It seemed that Khmel'nyts'kyi was on the verge of obtaining all he had

wanted. Events were not to leave him in peace,

however. Other Cossack leaders, like the popular Maksym Kryvonis and Danylo

Nechai, led the peasant masses and unregistered Cossacks in new revolts which

heaped further destruction on Roman Catholic Poles, Uniate Ukrainians, and

Jews throughout the Kiev palati¬nate. These revolts had a particularly

devastating impact, in both the short and the long term, on the Jews (see

chapter 27). The number of Jewish victims during the period from 1648 to 1652

has been estimated at from the tens to the hun¬dreds of thousands, and no

exact number is ever likely to be known. Whatever the exact number, or

whoever was responsible - the peasants, the Zaporozhian Cossacks and their

independent-minded leaders like Kryvonis and Nechai, or the Crimean Tatars,

who sold captured Jews in the Ottoman slave markets - it is Khmel'nyts'kyi

who is held to blame in Jewish sources to the present day. The widely used

Encyclopedia Judaica describes him with borrowings from Jewish chroniclers:

'"Chmiel the Wicked", one of the most sinister oppressors of the

Jews of all generations, ... and the figure

principally responsible for the holocaust of the Polish Jewry in the period.'

His reputation among Jews

remains unchanged, 'even though in reality,' the same source admits, 'his

control of events was rather limited.'1 Whatever the validity of Jewish

opinion about Khmel'nyts'kyi, the fact remains that in the socioeconomic

system of the Polish-Lithuanian Common¬wealth the Jews, alongside the Poles,

had come to represent the oppressor. In the great social upheaval which began

in 1648, the Jews found themselves caught between the proverbial hammer and

anvil, and the result was the destruction of many of their communities. Click

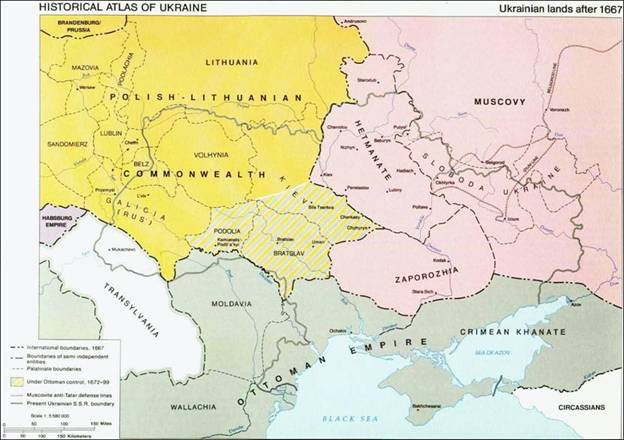

on the map for better resolution By the summer of 1648, the

Cossack-peasant revolts had spread farther west, into Podolia. At this point,

an influential polonized Ukrainian magnate from the Left Bank, Jeremi

Wisniowiecki, took matters into his own hands. Impatient with discussions of

the Cossack question on the part of the Polish government in Warsaw,

Wisniowiecki decided to attack the rebels. He was repulsed, however, by

Kryvonis. This development also prompted Khmel'nyts'kyi to come out of his

short-lived seclusion. He marched westward toward Volhynia, where in

September 1648, together with Kryvonis, he routed a

large Polish army of 80,000 soldiers near the village of Pyliavtsi. The

Cossack army then moved on to L'viv, where after suc-cessfully cutting off

the city from outside aid, they accepted a ransom from the urban authorities.

Now the way to Warsaw was open, and Khmel'nyts'kyi was urged by his Cos¬sacks

to strike there, at the heart of Poland. He set out in the direction of

Warsaw but in November stopped at Zamosc, about a third of the way between

L'viv and Warsaw. Once again, in the hope of gaining greater concessions from

the Polish government, Khmel'nyts'kyi preferred negotiation. The hetman's

conditions were the following: (l) that traditional privileges be restored to

the Cossacks; (2) that free access to the Black Sea, without Polish forts

like Kodak to block their way, be granted them; (3) that the right to depend

on the king alone, not on local Polish officials, be given the hetman; (4)

that amnesty be extended to all partici¬pants in the rebellion; and (5) that

the Union of Brest and thus the Uniate church be abolished. The new king, Jan

Kazimierz (reigned 1648-1668), prom¬ised to do his best to fulfill these

conditions. He asked Khmel'nyts'kyi to cease hostilities and to return home

in the meantime.

Prince

Jeremi Wisniowiecki Considering the broken Polish

promises in the past - whether because of an absence of good will on the part

of the king or, more likely, the interference of the Polish nobility - one

might well wonder how it was possible for Khmel'nyts'kyi to believe things

would be different this time. But whether or not he believed the Poles,

Khmel'nyts'kyi still hoped to function within the Polish-Lithuanian

Com¬monwealth. As a result, he agreed to put a stop to unruly Cossack and

peasant rebellions and to return home. Khmel'nyts'kyi as a national leader The hetman's attitude began to

change, however, after his arrival in Kiev. At the head of a victorious

Cossack army, which had within the space of less than a year defeated

Poland's leading military forces, Khmel'nyts'kyi entered Kiev on Christ¬mas

Day (according to the Julian calendar) in January 1649. There he was greeted

by the Orthodox metropolitan of Kiev, Syl'vestr Kosiv, and by the patriarch

of Jerusalem, Paisios, who was in Kiev at the time. As they had done with

Hetman Sahaidachnyi in 1620, the Orthodox hierarchy provided a religious and

national ideological context for Khmel'nyts'kyi's actions. The hetman was

called a mod¬ern-day Moses who had succeeded in leading his Ruthenian people

out of Polish bondage. In the opinion of the Orthodox leadership, the events

of the past year had a bearing on the religious and cultural survival of the

whole Ruthenian people (Ukraini¬ans and Belarusans), and not just the

particular interests of a single group, whether Khmel'nyts'kyi himself, or

the registered Cossacks, or the Zaporozhian Host as a whole. Patriarch

Paisios was particularly concerned with the interna¬tional implications of

the events in Ukraine. With the long-term goal of mobilizing the whole

Orthodox world to free the church from the Ottoman yoke, the patriarch urged

Khmel'nyts'kyi to work in close harmony with the neighboring Danubian

principalities of Moldavia and Walachia and to recognize the authority of the

tsar of Muscovy. Khmel'nyts'kyi was undoubtedly

affected by the new role conferred upon him. He is reported to have said to

commissioners of the Polish king: 'I have hitherto undertaken tasks which I

had not thought through; henceforth, I shall pursue aims which I have

considered with care. I shall free the entire people of Ruthenian from the

Poles. At first I fought because of the wrongs done to me personally; now I

shall fight for our Orthodox faith.... I am a small and insignificant man, but

by the will of God I have become the independent ruler of Ruthenia.' Whether or not Khmel'nyts'kyi

fully grasped the leadership role in which fate had cast him, in practical

terms it was impossible for him to control the peasant uprisings or to expect

that the masses, having had a taste of freedom, would calmly return home to

their duties within the Polish socioeconomic system. Moreover, the hetman

must have been impressed by the Orthodox hierarchy's expecta¬tions of him,

expressed by no less than a patriarch from the Holy Land itself.

Khmel'nyts'kyi proceeded to undertake diplomatic negotiations with Moldavia.

Walachia, Muscovy, and its allies the Don Cossacks, as well as with

Protestant Transylvania and the Lithuanian Prince Radziwill, who because of their

own anti- Catholic interests might help him in his anti-Polish efforts. By

the spring of 1649. when the king's negotiator Adam

Kysil' - himself an Orthodox Ruthenian nobleman loyal to Poland - met with

Khmel'nyts'kyi again, the change in the Cossack hetman was evident.

Khmel'nyts'kyi now called himself 'Autocrat of

Ruthenia by the Grace of God' and talked of liberation for all the Ruthenian

people living in the Polish- Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Adam

Kysil' It seemed inevitable that

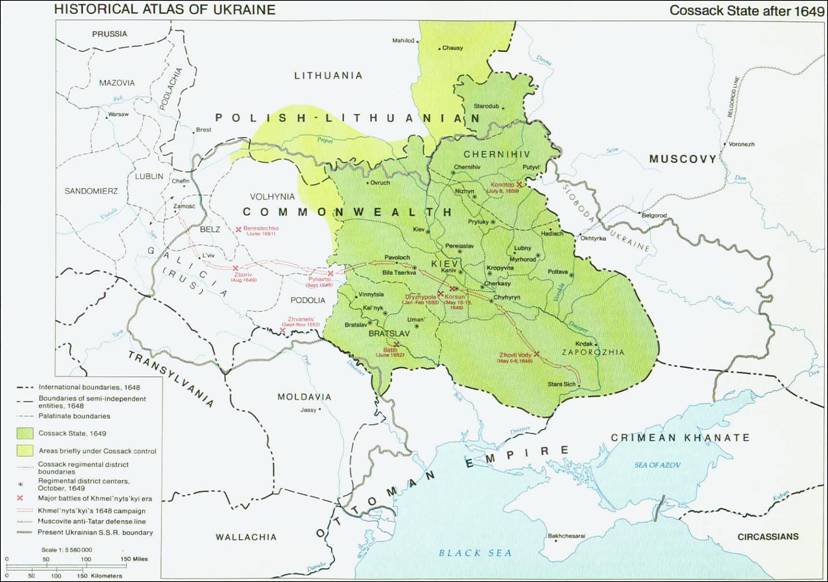

hostilities would break out again. By the summer of 1649, Khmel'nyts'kyi,

together with his CrimeanTatar allies, had surrounded the Polish army led by

King Jan Kazimierz at Zboriv. A peace, or, more precisely, a truce, was

signed in August whereby (1) the number of registered Cossacks was raised to

40,000; (2) the Kiev, Chernihiv, and Bratslav palatinates (collectively known

as Ukraine) were declared Cossack territory, to be rid of the Polish mili¬tary,

Jews, and Jesuits; (3) the Orthodox metropolitan was to be given a seat in

the Polish Senate; and (4) an amnesty was declared for nobles who had

participated in the uprising. Apart from the 40,000 on the register, those

others who called themselves Cossacks as well as the rebellious peasants were

expected to return as serfs to their landlords. While the clergy and Cossack

officers were satisfied with the Zboriv agreement, the peasants and

peasants-turned-Cossack clearly were not. Khmel'nyts'kyi once again

seemed to be wavering in his role as leader of the whole Ruthenian (Ukrainian

and Belarusan) society. After all, he was imbued with gen¬try values and

concerned with social stability; he was not a revolutionary who favored the

overthrow of the social order. In any case, the Zboriv peace gave him a

convenient respite in which to begin organizing a structure for the rapidly

expanding Cossack state. He made Chyhyryn the hetman's capital and from there

conducted extensive diplomatic negotiations in an effort to find allies who

would share his vision of eastern Europe. Khmel'nyts'kyi's vision

departed from the traditional approach of the Chris¬tian powers, whether that

of Catholic Poland and the Habsburgs or that of Ortho-dox Muscovy backed by

the Eastern patriarchs. The traditional alliances had instinctively been

directed against the Ottoman 'infidels.' Khmel'nyts'kyi, how-ever, hoped to

form a great coalition of Orthodox, Islamic, and Protestant powers -

Moldavia, the Ottoman Empire, the Crimean Tatars, Transylvania, and

Lithua¬nia's powerful Protestant figure Prince Radziwill - to force Poland's

rulers to make structural changes in their society. The Cossack hetman also

hoped to entice Poland's rival in the west, Brandenburg, and even Cromwell's

Protestant England into helping him force the restructuring of the

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a federation of three equal states -

Poland, Lithuania, and Ukraine - to be headed by a new king, Gyorgy Rakoczi

of Transylvania. The key to this grandiose scheme

was initially the Danubian principality of Moldavia, where Khmel'nyts'kyi and

the Tatars led a campaign in 1650 to force the Moldavian ruler (Vasile Lupu)

to give his daughter in marriage to the het- man's son, Tymish. The marriage

finally took place in 1652, but only after further Cossack military

intervention, which alarmed neighboring Walachia and Tran¬sylvania and led to

war with those two states and the death of Tymish in 1653.

Prince

Jeremi Wisniowiecki at Berestechko Khmel'nyts'kyi's war with the

Poles continued while he was being drawn into Danubian politics. The

attempted alliance with Lithuania's Prince Radziwill failed (the prince instead

sided with the Poles and captured Kiev during the Polish- Cossack conflict of

1651); the Cossacks were defeated in June 1651 at the Battle of Berestechko,

in Volhynia; and Khmel'nyts'kyi agreed to abide by conditions set in the

peace treaty signed at Bila Tserkva (September 1651). The Bila Tserkva

agree¬ment reduced the number of registered Cossacks to 20,000 and restricted

their residence to the royal lands of the Kiev palatinate. The Bratslav and

Chernihiv palatinates were returned to Polish governmental administrators,

and nobles were allowed to return to their estates. Although the Bila Tserkva

treaty was never rati¬fied by the Polish Diet (it was blocked by the

application of one member using the privilege of the liberum veto),

Khmel'nyts'kyi upheld its provisions, even sending Cossack detachments to put

down peasant uprisings against returning Polish noblemen in the Kiev

palatinate. Not surprisingly, the hetman's actions caused great discontent

among the peasants and unregistered Cossacks, who in despera¬tion moved

farther east to lands along the upper Donets' and Don Rivers that were under

Muscovite control. There they were allowed to form tax-exempt settle¬ments,

known as slobody, from which the whole region got its name - the Sloboda

lands, or Sloboda Ukraine. Khmel'nyts'kyi was able to defeat Polish armies in

1652 (at Batih, in Bratslav) and in 1653 (at Zhvanets', in Podolia), and in

the treaty signed at Zhvanets' (December 1653) the favorable conditions

established by the 1649 Zboriv treaty were restored. It was becoming increasingly

clear to Khmel'nyts'kyi, however, that his efforts against the Poles could at

best end in a stalemate, with no real improvement for the Cossack lands

within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Also, with the death of his son,

Tymish, in August 1653, it was equally evident that the hetman's diplomatic

effort to create a grand coalition against Poland had become entan¬gled in

the uncertainties of Danubian politics and in the end had produced noth¬ing

positive. Even his military alliances with the Crimean Tatars had proved

uncertain at best - the khans having chosen to negotiate independently with

the Poles during the battles at Zboriv (1649) and Zhvanets' (1653) and having

retreated at a critical moment during the battle at Berestechko (1651).

Finally, Khmel'nyts'kyi's intention to submit as a vassal to the Ottomans

(his submission was proposed in 1650 and confirmed by Istanbul in 1652)

resulted in little more than the sultan's urging the Crimean khans to help

the Cossacks. With failure evident in all corners, there seemed only one

course of action left whereby Khmel'nyts'kyi might break the military and

political stalemate with Poland. That alternative was the tsardom of Muscovy,

and it is there that Khmel'nyts'kyi turned next. Muscovy and the Agreement of

Pereiaslav Khmel'nyts'kyi's efforts to

create an international coalition of the Cossacks, the Ottoman Empire, and

its vassal states directed against Poland had failed. The ongo¬ing military

conflict with Poland moreover, had reached a stalemate. Accordingly, by 1653

the Cossack hetman had been forced to conclude that forming an alliance with

Muscovy might be the sole means of helping the Ruthenian-Ukrainian cause. In

fact, at the instigation of the visiting Orthodox patriarch of Jerusalem, the

Zaporozhian Cossacks had been negotiating with Muscovy since the very outset

of the 1648 rev¬olution, and the discussions became more frequent beginning

in early 1652. But what was Muscovy's view of the Cossack problem and, in

particular, of the Ukrain¬ian territories? And what did the tsar and his

advisers think of Khmel'nyts'kyi's con¬tinual requests to form an alliance?

Before trying to answer these questions, it is necessary to glance, however

briefly, at developments in Muscovy itself. Muscovy was only one, and

initially not the most important, of the several northern Ruthenian lands

which followed a separate historical development after the transformation of

Kievan Rus' in the thirteenth century. At that time, Muscovy was a

principality within the Grand Duchy of Vladimir-Suzdal', which, alongside

Novgorod, was the most powerful center in northern Rus'. From their capital

city, Vladimir-na-Kliazma, the rulers of Vladimir-Suzdal' claimed they were

the successors of the grand princes of Kievan Rus'. It was also to

Vladimir-na-Kliazma that the head of the Orthodox Ruthenian church, the

metropolitan of Kiev, went after the Mongol invasion, and eventually, in

1299, he transferred his residence there. But any possibility of the northern

Ruthenian lands' being united under the leadership of Vladimir-na-Kliazma or

any other city was thwarted by the Mongols of the Golden Horde. The Mongols'

military strength enabled them to enforce a policy whereby the northern Rus'

principalities, whose rulers were their vassals, remained inde¬pendent of one

another and dependent solely on the khans in their capital at Sarai, on the

lower Volga. The rise of Muscovy It was precisely during the

period of greatest Mongol political influence in the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries that the

various principalities within the Grand Duchy of Vladimir-Suzdal' (Rostov,

Suzdal', Tver', and others) increas¬ingly asserted their independence. Among

them was Muscovy, which also proved the most deferential to Mongol rule. As a

result, Muscovy was granted certain favors by the Golden Horde. In the

fifteenth century, by which time the Golden Horde had itself broken up into

three khanates (the Crimean, the Astrakhan', and the Kazan'), the Grand Duchy

of Muscovy, led by a series of talented and able rulers, took the opportunity

to begin uniting the northern Rus' lands. This proc¬ess was largely completed

during the reign of Grand Duke Ivan III (reigned 1462- 1505) at the beginning

of the sixteenth century. It is important to note that Ivan III considered as

part of his goal to gather together not only the northern, or Rus¬sian,

territories of former Kievan Rus', but the Belarusan and Ukrainian

territo¬ries as well. Muscovy, however, was not yet completely independent of

the Kazan' and Astrakhan' Tatar khanates along its eastern and southeastern

borders, which claimed the annual tribute formerly paid to the Golden Horde.

Nor was Muscovy a match for the powerful Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which

firmly controlled the Ruthenian (Belarusan and Ukrainian) lands in the west

and south. The Grand Duchy of Muscovy consequently had for the

moment to be content with control only over the northern Rus' lands. But

ideologists around Ivan III seemed to be preparing for the future. They

emphasized Muscovy's supposed right to the so-called Kievan inheritance,

implicit in Muscovy's considering itself a 'Second Kiev' - the political and

cultural successor to Kievan Rus'. Also of sym¬bolic importance was the

marriage of Ivan III, a descendant of the Riuryk dynasty, to a Byzantine

princess, which linked Muscovy (as similar marriages had linked Kievan Rus'

centuries before) with the imperial heritage of Byzantium. Moreover, the head

of the Orthodox Rus' church, who retained the title Metropolitan of Kiev and

All Rus', under pressure from Muscovite rulers had transferred his resi¬dence

from Vladimir-na-Kliazma to Moscow in 1328. Then, in the mid-fifteenth

century, on the eve of Ivan Ill's accession to power, the Muscovite church

began its evolution toward autocephaly. Beginning in 1448, the metropolitans

in Mos¬cow were elected without the approval of the ecumenical patriarch in

Constantinople. Ecclesiastical circles also made possible the revival of

chronicle writing in Muscovy and other northern Rus' lands, in which scribes

composed new texts and 'improved' on the old with the object of having all

such accounts support the dynastic claims of the Muscovite princes that they

were descended from Riuryk and his Kievan successors Volodymyr the Great and

Iaroslav the Wise. Finally, under Ivan Ill's successor, Vasilii III (reigned

1505-1533), the idea of Moscow as the Second Kiev was enhanced by the use of

an even more prestigious epithet whereby Moscow became the 'Third Rome.' Thus, by the beginning of the sixteenth century,

Muscovy had all the ideological symbols necessary for implementing its claim

to be the political successor of Kievan Rus', the inheritor of the Orthodox

mantle from Byzantium (which had fallen in 1453), and therefore the rightful

ruler of all the East Slavs who inhabited the Rus' patrimony - Russians,

Belarusans, and Ukrainians. But much still had to be accomplished in the realm of

politics. In large measure, it was accomplished during the second half of the

sixteenth century under the Muscovite ruler Ivan IV (reigned 1547-1584),

known in history by the epithet 'the Terrible,' or, more precisely, 'the

Dread.' Ivan IV was the first Muscovite ruler to be crowned as tsar, or

absolute ruler in the tradition of Rome's caesars. His realm was thereby

transformed into the tsardom of Muscovy, with a nominal claim to universal

rule. Under Ivan IV, the domination of the Tatars was finally broken as both

the Kazan' and the Astrakhan' khanates were destroyed. With his eastern flank

secured, the aggressive tsar was able to turn his attention to the west.

There the results were mixed. Although in 1558 the Muscovites were finally

able to break the power of the Livonian Knights (the last of the Teutonic

military orders to survive along the Baltic Sea in what is present-day Latvia

and Estonia), their doing so created a power vacuum into which Sweden and

Lithuania entered. The consequence was almost a quarter century of cosdy wars

between these two powers as well as against Muscovy for control of Livonia.

It was also during these struggles that the borderland between Muscovy and

Lithuania - the regions around Smolensk, Starodub, and Chernihiv - changed

hands several times. And it was this Muscovite threat to Lithuania's eastern

borders that encouraged the grand duchy to draw closer to Poland and to agree

to the Union of Lublin in 1569. Such foreign military campaigns were extremely costly

to Muscovy, and at the time of Ivan IV's death in 1584 the tsardom was in a

shambles. The limited success of Ivan's foreign ventures was matched by the

disastrous results of his domestic policies. These policies were directed at

weakening the power of the boyars, the wealthy magnates who had ruled Muscovy

during his youth. Despite Ivan's brutal methods, the boyars were not entirely

eliminated as a political force. When the tsar died in 1584, he left no

suitable successor. This was because he had murdered his eldest son with his

own hands in a characteristic fit of rage in 1581; his succes¬sor Dmitrii

died under mysterious circumstances in 1591; and his only other legitimate

heir, Fedor, was mentally retarded. Consequently, the tsardom of Muscovy

entered a period of boyar rule that was to last almost three decades. Marked

by widespread civil war, famine, and foreign invasion, this period came to be

known as the Smutnoe Vremia, or Time of Troubles. The very existence of the

Muscovite state seemed to hang in the balance. Muscovy,

Poland, and Ukraine It was during Muscovy's Time of Troubles that Poland, strengthened

after its unification with Lithuania in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in

1569, came to play a dominant role in Muscovite politics. Polish-Lithuanian

armies invaded Muscovy several times at the beginning of the seventeenth

century. The Poles supported a pretender to the Muscovite throne (the

so-called False Dmitrii), and after 1608 Poland's King Zygmunt III put forth

his own son, the future Wladyslaw IV, as a candidate for tsar. With the help

of the Zaporozhian Cossacks under Het- man Sahaidachnyi, the Poles occupied

Moscow on several occasions. Although Polish forces were finally driven out

in 1612, Wladyslaw IV, who was elected king of Poland in 1632, continued for

the next few years to claim the Muscovite throne. In 1613, Muscovy's Time of Troubles came to an end with

the election of a new tsar, Mikhail Romanov (reigned 1613-1645). He became

the founder of a new dynasty, the Romanovs, who were to rule Muscovy and

later the Russian Empire until 1917. Tsar Mikhail and his successor, Aleksei

(reigned 1645-1676), succeeded in restoring order within the Muscovite

tsardom. It was also during their long reigns that the basis of the modern

Russian state evolved. That state was marked by one overriding characteristic

- centralized authority. By the last years of Mikhail's reign in the 1640s,

the power of the aristocratic boyars (as expressed in their council, the

Zemskii sobor) had diminished, and a bureaucratic structure had been set up

throughout Muscovite territory to act as a conduit for all authority, which

rested in the person of the tsar. Special chancelleries were established in

Moscow to admin¬ister towns and rural areas. It was through these

chancelleries that the central government issued decrees (gramoty)

instructing the residents of each town and rural district how to run their

administrations. Soon nothing could be done in the tsardom without

instructions from the chancelleries in Moscow. Complementing this

administrative structure was a social structure that became highly stratified

as well. Each individual from the tsar down to the peasant had a given place

in society, and the primary function of each was service to the state. Such

stratification allowed for a stable tax base from which the central authority

could draw funds. Accordingly, by the mid-seventeenth century the two

states which had come to control most of eastern Europe - Poland and Muscovy

- had completely different political structures. Whereas in Poland the

authority of the elected king was circumscribed by the Polish nobility

(magnates and gentry) through the central Diet (Seym) and local dietines

(sejmiki), and whereas in the countryside the resident magnates and gentry

ran their properties as autonomous entities with almost no interference from

a central government, in Muscovy the boyars (magnates) had lost their

political prerogatives to a hereditary tsar who ruled the country through an

increasingly complex bureaucratic system in which, correspondingly, it became

more and more difficult to act without the approval of the central

government. In one respect, Poland and Muscovy were similar. Both

came to establish socio-economic and judicial systems that transformed their

respective peasant populations into serfs. In Muscovy, that process began in

the late fifteenth century and was complete by the mid-seventeenth century.

In 1649, a new law code (the Ulozhenie) outlined fully all aspects of the

service state, in which the primary function of each individual was service

to the state. The code, which remained the basis of Russian law until as late

as 1833, legalized serfdom and bound the peasants to the land. Land was often

awarded to the Orthodox church or to individuals within the military or civil

service, and the serfs attached to land that became their property were forbidden

to leave it. It was during the Time of Troubles (1584—1613) that

Ukrainians increased their contacts with Muscovy. Registered Cossacks who

served in the Polish army participated in Poland's numerous invasions of

Muscovite territory, which thus became a source of booty. Before long,

however, Muscovy became for Ukrainians not simply a place to raid, but a

source of aid. This was particularly the case with regard to religious

affairs. As a result of the Union of Brest in 1595, the Orthodox

church was outlawed in Poland-Lithuania. Although the church managed to

survive in that country's Ukrainian- and Belarusan-inhabited lands, thanks to

the dedication of a few Ruthenian magnates, the brotherhood movement, the

monasteries, and the political pre¬sure of the Cossacks, its situation

remained precarious. This continued to be true even after 1632, when the

Orthodox hierarchy was finally permitted to function legally once again.

Consequently, during the decades following the Union of Brest the beleaguered

Orthodox church in Poland sought help from other Ortho¬dox states, in

particular Muscovy. By the 1620s, Ukrainian monasteries were making

frequent requests to the Orthodox tsar in Moscow for money to build churches

or to purchase vestments. Then, beginning in 1623 and each year thereafter

Ukrainian monks arrived in Putivl', Okhtyrka, and other towns along the

Polish-Muscovite border begging the tsar to allow them to come to Muscovy in

order to practice 'the Christian [Orth¬dox] faith, which the Poles want to suppress.'1

At the same time, Orthodox hier- archs like Metropolitan Iov Borets'kyi of

Kiev and Bishop Isaia Kopyns'kyi of Przemysl, both secretly consecrated in

1620 but not recognized by the Polish government, sent messages or traveled

personally to Muscovy, asking the tsar to take their land and its inhabitants

under his 'mighty hand.' Even after the Orthodox church hierarchy of

Poland-Lithuania was legalized in 1632, traditionalist hier- archs continued

to express pro-Muscovite attitudes, especially as they were in opposition to

the pro-Polish and Latin-oriented policies of the new Orthodox metropolitan

of Kiev, Petro Mohyla. Finally, large numbers of peasants and discontented

Cossacks sought refuge by fleeing to Muscovy. Even before the outbreak of the

revolution, in the decade between 1638 and 1648, as many as 20,000 people

emigrated from the Left Bank to Sloboda Ukraine, the free-settlement frontier

just north of what is today Kharkiv and the

Russian-Ukrainian border. The migrants went east for several reasons. They

were fleeing the spread of Poland's expanding manorial system, or they were

refugees from the Cossack uprisings, the most recent being the unsuccessful

ones in 1637 and 1638. Also, in general they hoped to find greater

psycho¬logical and physical security under tsarist rule. Precisely what kind of psychological and physical

security? First, the Orthodox Ukrainians and Belarusans of Poland-Lithuania

would no longer be discriminated against or persecuted for their religion

under tsarist rule. Second, Muscovy offered greater protection against Tatar

raids, which, despite the existence of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, still took

their annual toll of the Ukrainian population. The Polish response to the

Tatar threat was to build fortified centers near the edge of the steppe zone,

staffed, usually, with registered Cossacks. The Tatars naturally could and

did ride around these centers. In contrast, the Muscovites, beginning in the

late sixteenth century, built a series of solid walls (zasechnaia cherta) consisting of felled trees and palisades of

sharply pointed logs inter¬spersed with fortified cities. These lines were

built progressively farther south until a major defence system known as the

Belgorod Line had been constructed, between 1635 and 1651. The Belgorod Line

ran for more than 480 miles (770 kilometers) from Okhtyrka, near the Polish

border, straight across Sloboda Ukraine through Belgorod and on to Voronezh,

father northeast (see maps 16 and 20). Along this line twenty cities were

founded between 1637 and 1647, half of them in Sloboda Ukraine. An extension

of the Belgorod Line was built farther south toward the Donets' River. Behind

these lines emigrants from Ukraine sought refuge. Thus, Orthodox inclinations

and migrational patterns revealed that a pro-Muscovite attude among

Ukrainians had existed long before Bohdan Khmel'nyts'kyi ever came on the

scene. Khmel'nyts'kyi

and Pereiaslav Khmel'nyts'kyi himself had become part of this

pro-Muscovite trend. Despite his victories in May 1648 over the Polish armies

at Zhovti Vody and Korsun', the Cossack hetman remained concerned that the

conflict with Poland was not yet over. Hence, between June 1648 and May 1649

he addressed seven letters to Muscovy asking for military assistance,

offering Cossack services to the tsar, and expressing the hope that at the

very least the Muscovite army would not attack his Tatar allies. At that very

moment, however, the tsar was incapable of action, since Moscow itself was

facing a serious revolt that was to last through the summer and early fall of

1648. Moreover, the nineteen-year-old, still politically weak Tsar Aleksei

was reluctant to antagonize Poland, which he would certainly do if a

Muscovite- Zaporozhian alliance were concluded. While it is true that at the beginning of the

seventeenth century Muscovy had succeeded in re-establishing internal order

after the Time of Troubles, in foreign affairs the tsardom remained on the

defensive, especially vis-a-vis Polish military might. For instance, as late

as 1634, Polish kings still laid claim to the Muscovite throne, and after

military campaigns in 1618 and again in 1633-1634 Muscovy was forced to give

up to its western rival territories around Smolensk and Severia (including

Starodub and Chernihiv). Faced with continual Crimean Tatar raids from the

south and a potential Swedish invasion of Livonia, along the Baltic Sea,

Muscovy did not feel it could afford to alienate Poland. Thus, Tsar Aleksei's

refusal of Khmel'nyts'kyi's requests in 1648-1649 was understandable. Khmel'nyts'kyi's victories during the next two years,

however, revealed that Poland's armies were not invincible after all.

Consequently, when the Cossack leader, having exhausted his Balkan and

Ottoman foreign policy ventures, turned to Tsar Aleksei on numerous occasions

between 1652 and 1653, much had changed. The Russian Orthodox church, led by

its new and enterprising patriarch Nikon (reigned 1652-1681), was anxious to

reform itself by using the intellectual talents of Ruthenian churchmen

trained in Mohyla's Collegium at Kiev. Nikon, who was the tsar's closest

adviser on Ukrainian matters, urged the Muscovite government to support the

Cossacks' requests. It is not surprising, therefore, that it was the Russian

Orthodox patriarch who was serving as the mediator when in April 1653

Khmel'nyts'kyi's envoys asked the tsar to extend his protection over the

Cossacks. Finally, in June of that year, Tsar Aleksei agreed to accept the

Zaporozhian het¬man and his Cossacks 'under the tsarist majesty's high arm.' As a result of this decision, Muscovite ambassadors

were dispatched in late December 1653 to meet with Khmel'nyts'kyi. The

meeting place chosen was the town of Pereiaslav, along the Dnieper River,

halfway between Kiev and the het- man's capital of Chyhyryn. According to

Muscovite sources, on the day of the ambassador's arrival the local

archpriest led a multitude of Pereiaslav's citizens to greet the Muscovite

envoys and to 'thank God for having fulfilled the desire of our Orthodox

people to bring together Little and Great Rus' under the mighty hand of the

all-powerful and pious eastern tsar.'2 The negotiations at Pereiaslav lasted for several days

during the month of January 1654. Disagreements arose because the Cossacks expected

that the tsar would swear an oath to them, as was the practice for Polish

kings. Moreover, the Orth¬dox metropolitan of Kiev, Syl'vestr Kosiv (reigned

1647-1657), was opposed to negotiations that he feared would lead to the

subordination of his jurisdiction to the patriarch of Muscovy. In the end,

Khmel'nyts'kyi and the Cossacks did swear an oath of allegiance to the tsar,

after which the Muscovite envoys were sent to sev¬eral other Ukrainian cities

to administer the oath. The 1654 agreement

of Pereiaslav, which resulted in the union of the Cossack- controlled

territory of Ukraine with Muscovy, actually consisted of three elements: (1)

the oath sworn by the Cossacks and the people of Pereiaslav and other Ukrain¬ian

cities in January 1654; (2) Khmel'nyts'kyi's twenty-three 'Articles of

Petition,' brought to Moscow by his delegates in March 1654; and (3) the

tsar's response in the form of eleven articles issued later that same month.

In addition, several charters were issued between March and August 1654.

These various charters included agreement as to certain basic principles. The

Cossacks and the Ukrainian people as a whole swore allegiance to the tsar.

The Zaporozhian army was granted confirmation of its rights and liberties,

including the independence of Cossack courts and the inviolability of Cossack

landed estates. The Zaporozhian army was to elect hetmans, who must swear

allegiance to the tsars. Chyhyryn was to remain the het- man's capital, from

which relations with foreign countries (with the exception of Poland and the

Ottoman Empire) could be conducted. The number of registered Cossacks was

fixed at 60,000, all of whom were to receive wages from that part of the

revenue from Ukraine to which the tsar was entitled. The tsar would provide

the Cossacks with military supplies. The traditional rights of the Ukrainian

nobility were confirmed. Urban dwellers could elect their own municipal

govern¬ments. Finally, the Orthodox metropolitan and other clergy throughout

Poland- Lithuania were to be 'under the blessing' of the patriarch in Moscow,

who promised not to interfere in ecclesiastical matters.

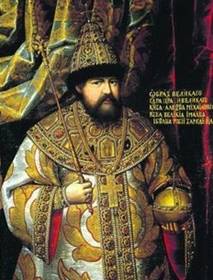

Alexey Mikhaylovich

Romanov (1629-1676), Tsar of Russia When the negotiations between the Cossack envoys and

the Muscovite govern¬ment were finally completed in August 1654, the tsar's

title was changed from Tsar of All Rus' (vseia

Rusii) to Tsar of All Great and Little Rus' (vseia Velikiia i Malyia Rusii). Thus, without having made any

special effort, Tsar Aleksei had taken a sig¬nificant further step toward

Muscovy's goal, set out in the late fifteenth century by Grand Duke Ivan III,

to unite under one Orthodox ruler all the lands formerly within the sphere of

medieval Kievan Rus'. The agreement of

Pereiaslav subsequently proved an important turning point in eastern

European history. It signaled a gradual change whereby Muscovy, not Poland,

became the dominant power in the region. As for Ukraine, 1654 ended a

six-year period which marked the culmination of more than a half century of

Cossack struggle for autonomy within Poland. When the Polish solution no

longer seemed feasible, the Cossacks sought autonomy within Muscovy instead. Historians have debated at length the juridical

significance of the agreement - or treaty, as some say - at Pereiaslav. Some

consider it to reflect the incorporation of Ukraine into the tsardom of

Muscovy with guarantees for autonomy, whether based on a treaty (B.E. Nolde)

or on personal union (V. Sergeevich). Others consider Ukraine to have become

a kind of semi-independent vassal state or protec¬torate of Muscovy (N.

Korkunov, A. Iakovliv, M. Hrushevs'kyi, L. Okinshevych).

Still others see it as no more than a military alliance between the Cossacks

and Muscovy (V. Lypyns'kyi), or an 'atypical' personal union between two

juridically equal states (R. Lashchenko). Aside from the debates among legal scholars and

historians, Pereiaslav and its reputed architect, Bohdan Khmel'nyts'kyi, have

taken on a symbolic force in the story of Ukraine's relationship with Russia

and have become the focus of either praise or blame. For instance, in the

nineteenth century the Ukrainian national bard, Taras Shevchenko, designated

Khmel'nyts'kyi the person responsible for his people's 'enslavement' under

Russia (see chapter 28). The government of Tsar Alexander III (reigned

1881-1894), however, erected in the center of his¬toric Kiev a large equestrian

statue of Khmel'nyts'kyi, his outstretched arm point¬ing northward as an

indication of Ukraine's supposed desire to be linked with Russia. After World

War II, the Pereiaslav myth was resurrected, this time by Soviet ideologists,

who, on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the agreement in 1954,

transformed the event into the ultimate symbol of Ukraine's 'reunifica¬tion'

with Russia, from whom it had been forcibly separated by foreign occupation

since the fall of Kievan Rus' Whatever writers subsequently have speculated about

Pereiaslav, one thing is certain: after 1654, the tsardom of Muscovy - which

within seventy-five years would be transformed into the Russian Empire -

considered Malorossiia (Little Russia, i.e., Ukraine) its legal patrimony.

Since the tsar considered Little Russia part of his Kievan Rus' inheritance,

whatever rights or liberties he granted the Cossacks at Pereiaslav were gifts

he could take back whenever he wished. But if Pereiaslav provided

legitimization for tsarist rule over Ukraine, for the highest Cossack

officers (the starshyna) it took on

the character of an institutional charter which they felt both defended and

guaranteed their administrative distinctiveness within the Russian Empire. Even though the tsar subsequently reconfirmed and even

amended 'Little Russian rights and liberties' whenever a new hetman took

office (1657, 1659, 1663, 1665, 1669, 1672, 1674, 1687), and even though new

wars would be fought and borders changed, the Ukrainian territory, basically

east of the Dnieper River, that was acquired in 1654 was henceforth to remain

within a Muscovite or Russian state. By the end of the eighteenth century,

further territorial acquisitions had been made whereby most Ukrainian lands

(with the exception of Galicia, Buko- vina, and Transcarpathia) found

themselves within the Russian Empire. It is with Pereiaslav, then, that one

can speak of the beginnings of a new Muscovite or Rus¬sian phase in Ukrainian

history. The Period of Ruin The agreement

concluded at Pereiaslav in 1654 resulted in an extension of Mucovy's

borders to include the Zaporozhian Cossacks and the Ukrainian-inhabited

Polish palatinates of Chernihiv, Kiev, and Bratslav, as well as the

Zaporozhian steppe farther south on both sides of the bend in the Dnieper

River. The agreement, however, did not bring peace to Ukrainian lands.

Rather, it ushered in, or, perhaps more precisely, simply continued, a period

of conflict marked by foreign invasion, civil war, and peasant revolts which

was to last uninterruptedly until 1686, when a so-called 'eternal peace' was

concluded between two of the three dominant powers in the region, Poland and

Muscovy. The years 1657 to 1686 at times witnessed an almost

complete breakdown of order. All or some of these years have been

characterized in Ukrainian history as the Period of Ruin (Ruina), whose very

beginning (1655-1661) is known in Polish history as the Deluge (Potop). These

characterizations represented the eastern variant of a series of political

and social convulsions that at the time were racking all of Europe, from

England and Ireland in the west to Russia in the east, and from Scandinavia

in the north to Italy and Spain in the south, referred to by historians as

'the crises of the seventeenth century.' In a sense, these crises represented

the culmination of a struggle which had been taking place for several

centuries within many European states, between a centralized authority,

usually vested in a king, on the one hand, and rival political centers, often

noble and urban estates, on the other. The struggle has also been viewed as a

phase in European history in which the political power of representative

assemblies (the English Parliament, the French Etats Generaux, the Muscovite

Zemskii Sobor, etc.) was either substantially reduced or entirely eliminated

and replaced by governing systems in which all power rested in the hands of

monarchs who, with their closely controlled administrations, attempted to

rule in a more efficient and, so they pretended, enlightened manner. In this new era of enlightened absolutism, states like

the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which maintained the tradition of

diffused power, seemed fated to lose ground against more highly centralized

and absolutist neighbors — whether Brandenburg in the west, Sweden in the

north, Muscovy in the east, or the Austrian and Ottoman empires in the south.

Moreover, the age did not augur well for those elements on the periphery of

established states, such as the Cossacks, whose desires for local autonomy

and the maintenance of an estates system in which they would have special

privileges were out of step with the general trend in European society. After

the seventeenth century, this trend favored the development of strongly

centralized and bureaucratized state structures. In this sense, it might be

argued that the efforts of the Cossacks to preserve their autonomy in Ukraine

represented an anomaly doomed from the start - unless, of course, they could

create an independent and centralized state structure of their own. Indeed, there were some Cossacks, especially from among

the registered and officer class (the starshyna),

who tried to create a distinct and viable state structure. But they were continually

opposed by unregistered and other independent- minded peasants-turned-Cossack

farther south in Zaporozhia, whose only goal seemed to be to maintain a

society free of any kind of control beyond their own traditional and

rudimentary democratic local order. Faced with these contradictions within

Cossack society, the only reasonable solution for those Cossacks seek¬ing

social stability was to attempt to obtain autonomy within some existing

state. In the short run, this solution proved feasible, although in the long

run loss of autonomy and absorption by the controlling state structure turned

out to be inev¬itable. The process, of course, which now appears inevitable

in historical hindsight, was neither apparent nor complete for at least

another century. The Period of Ruin between 1657 and 1686 can be seen as the

first stage in this long process. The Period of Ruin in Ukrainian history is marked by

such complexity that it will be possible to discuss only its basic outlines

here. Briefly, the period began with the death of Bohdan Khmel'nyts'kyi, by

which time Poland and Muscovy were already engaged in a war as a result of

Ukraine's placing itself under the sovereignty of the tsar in 1654. The

period ended in 1686 with an agreement between Poland and Muscovy to

recognize each other's sphere of influence over Ukraine, which they divided

roughly along the Dnieper River. Changing

international alliances The agreement of Pereiaslav in 1654 prompted an

immediate change in the alliance structure in eastern Europe. The new

Muscovite-Cossack alliance forced the Crimean Tatars, who were traditional

enemies of Muscovy, to break with the Cossacks and to form an alliance with

the Poles instead. Tsar Aleksei, feeling confident in the military potential

of his new subject, Bohdan Khmel'nyts'kyi, decided to launch a pre-emptive

attack on Poland as early as April 1654. His goal was not only to acquire the

long-disputed territories along the Muscovite-Lithuanian border, but also to

detach the Belarusan lands from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and to

include them in the recently created Muscovite-Ukrainian federation. In fact,

the Belarusan peasants rebelled against their Polish and Lithuanian

landlords, welcomed the tsar as liberator, and helped make possible Muscovy's

conquests in 1656 as far as Vilnius and Kaunas. At that point, Aleksei even

changed his title once again, this time from Tsar of All Great and Little

Rus' to Tsar of All Great and Little

and White Rus' (vseia Velikiia i Malyia

i Belyia Rusii). Aleksei seemed about to realize the age-old Muscovite

dream of uniting all the Orthodox lands that had once been part of Kievan

Rus'. Meanwhile, the Poles and their new Tatar allies were

ravaging the Bratslav palatinate in Ukraine, until Khmel'nyts'kyi, with Muscovite

help, finally fought them to a military stalemate in January 1655 (the Battle

of Dryzhypole). The Cossacks and Muscovites cooperated in military matters,

including operations in Galicia, but at the same time Khmel'nyts'kyi

continued to follow an independent diplomatic policy. For instance, he wanted

the newly conquered Belarusan lands incorporated into a Cossack state, and in

order to be certain that Poland would be permanently damaged he joined with

Poland's enemies to the north, west, and south - namely, Sweden, Brandenburg,

and Transylvania. All these states were led by Protestant rulers who hoped to

destroy Roman Catholic Poland once and for all. Sweden's armies under King

Charles X Gustav (reigned 1654-1660) invaded Poland

in 1655 and captured both Warsaw and Cracow. Sweden was joined by

Brandenburg, which had its own designs on Polish-controlled Prussia.

Eventually, Lithuania (led by the son of the Protestant Janusz Radziwill) and

the majority of Poland's nobility recognized Sweden's Charles X as their

king. Click

here to read more about the events in

Poland and around it during the described

period It was precisely at this moment, when Poland was at its

nadir, that a wave of patriotism spread through the

country, inspired by accounts of the defence of the Catholic monastery of

Czestochowa. The otherwise politically contentious and militarily passive

nobility was moved by a new-found sense of patriotism and united behind their

king. With support from Poland's nobility, assistance from the Tatars, and

the signing of a truce in November 1656 with Muscovy (who now feared the

expansion of Swedish influence), King Jan Kazimierz was able to restore his

authority. Khmel'nyts'kyi, meanwhile, was disturbed by Muscovy's

truce with Poland. Since he considered himself a free political agent

(notwithstanding agreement of Pereiaslav),

he took the opportunity to renew diplomatic alliances with Moldavia,

Walachia, and Transylvania in the south and with Lithuania, Branden¬burg, and

Sweden in the north. This move reflected a basic change in his diplomatic

orientation, from dependence on the Islamic world (the Ottoman Empire and the

Crimea) to alliance with Protestant northern and southern Europe (Sweden. Brandenburg, and Transylvania), which he hoped might bring

independence for Cossack Ukraine. According to the negotiations over the

future division of Poland, the Cossacks and each of the Protestant allies

were to obtain parts of the kingdom. These plans all hinged on the military success of

Sweden. Charles X, however, was for the moment interested in the Brandenburg

theatre of operations. Moreover, the Swedish king faced political difficulties

at home which forced him to withdraw his troops from Poland during the second

half of 1656. In the end, the grand alliance was limited to Transylvanian

troops under the Hungarian Protestant prince Gyorgy II Rakoczi (reigned

1648-1660) and Khmel'nyts'kyi's Cossacks. But instead of cooperating, the

Zaporozhians and Transylvanians clashed over what each considered their

rightful share of territorial spoils in Galicia and Volhynia. Thus,

Khmel'nyts'kyi's grandiose diplomatic plans - this time based primarily on an

alliance with Protestant countries — failed once again to result in the

destruction of Poland. Moreover, the Cossack hetman's new diplomatic ventures

alienated the Muscovites and his recently acquired sovereign, Tsar Aleksei,

who in response tried to weaken Khmel'nyts'kyi's authority by sowing discord

within the Zaporozhian army. At this critical moment, in August 1657, the

hetman died. The pattern for Ukrainian politics set by

Khmel'nyts'kyi was to be followed by his successors. Unable to create an

independent state structure of their own, and desirous of acquiring an

advantageous position within some existing state, the Zaporozhian leaders

decided that their future and the future of Ukraine lay with Orthodox

Muscovy. Nonetheless, almost from the outset Khmel'nyts'kyi consid¬ered

himself independent of the tsar and was not averse to following an

independent foreign policy. Also, the long-standing friction between the

so-called Cossack starshyna (i.e., the hetman, his officers, and the well-to-do

registered Cossacks) on the one hand and the mass of more socially

undifferentiated Cossacks in Zaporo- zhia on the other — a friction which was

evident under Polish rule during the first half of the seventeenth century

and which surfaced on more than one occasion during the 1648 revolution — was

now being used by the Muscovite government for its own purposes. Essentially,

from their base at the sich along the lower Dnieper River the Zaporozhian

Cossacks and their peasant supporters favored the alliance with the tsar. For

its part, Muscovy used Zaporozhian loyalty as a counterweight to the

independent-minded policy of the hetman and the Cossack starshyna. Of course,

the Muscovite government knew that their erstwhile and somewhat reluctant

allies, the Cossack starshyna, were not averse to renewing traditional

alliances with the Poles if they felt doing so would bring them greater

advantages. The

Cossack turn toward Poland Khmel'nyts'kyi's successor, Hetman Ivan Vyhovs'kyi,

chose the Polish orientation. Vyhovs'kyi was elected hetman in 1657 by the

starshyna, but he was immediately challenged by Cossacks in the Zaporozhian

Sich. The reason was simple. Even the universally respected Khmel'nyts'kyi

had gotten his revolutionary start by going to the Sich and being chosen

hetman by its members. Hence, when Vyhovs'kyi tried to go around the Sich by

dealing directly with the starshyna, the Zaporozhians rebelled. The

rebellion, led by Iakiv Barabash and joined by Cossacks in the Poltava region

under Martin Pushkar, was aided by Muscovy. In the end, Vyhovs'kyi was able to defeat the

Zaporozhian rebels as well as their allies, although he remained disenchanted

with Muscovy's interference in Cossack affairs. While not breaking entirely

with the tsarist government, he signed a treaty with Sweden in October 1657

(at Korsun'), which promised the creation of an independent Cossack state

that would include Calicia and Volhynia as well as eastern Ukrainian lands.

When the Swedish alliance failed to produce concrete results, and when it

became clear that Muscovy would lend its support to the anti-starshyna

Cossack rebels, Vyhovs'kyi, with the counsel of his talented advisor Iurii

Nemyrych, decided to try once again to reach an accord with the Poles.

Nemyrych was a Ruthenian magnate who before 1648 had converted to

Protestantism and become one of Protestantism's intellectual mentors in

Poland. He subsequently served with the Polish army against Khmel'nyts'kyi

and later favored the election of a Protestant king to the throne of Poland,

from either Transylvania or Sweden. Finally, in 1657 Nemyrych entered the

service of Hetman Vyhovs'kyi, and soon afterward he returned to the fold of

Orthodoxy.

Ivan Vyhov’skyi

(Wyhowski), Hetman of the Ukraine in 1657-1659 Nemyrych promoted the idea that for Poland to survive

it should be transformed into a federation of three states - Poland,

Lithuania, and the Grand Duchy of Ruthenia. Although the Cossack negotiators

originally demanded that Galicia and Volhynia be part of the new state, in

the end the Grand Duchy of Ruthenia was to consist of the Ukrainian

palatinates of Kiev, Chernihiv, and Bratslav. Ruthenia, together with the two

other members of the tripartite federation, Poland and Lithuania, would sign

a mutual defence pact which also set as its goal the conquest of the shores

of the Black Sea. Muscovy could become part of the confederation should it so

desire. As for Ruthenia, it would have its own judicial system, treasury, and

mint and a Cossack register of 30,000 men to be paid by the government as

well as a standing army of 10,000 men under the Zaporozhian hetman. The

officers of these forces would be elected by their own members and, most

important, the Cossack starshyna would be recognized as a social estate equal

to the Polish gentry. In that context, each year the hetman would recommend

to the king 1,000 Cossacks to receive the hereditary patent of nobility.

Moreover, all Cossack and Polish landholdings confiscated after 1648 would be

returned to their original owners. Finally, the Uniate church would be

abolished within the Grand Duchy of Ruthenia; the Orthodox church would be

made fully equal to the Roman Catholic church throughout Poland-Lithuania;

Kiev's Orthodox Collegium would be raised to the status of an academy; and a

second Orthodox higher institution of learning would be established.

Nemyrych's final version of the treaty was put forward to the Poles in the

small town of Hadiach in September 1658. Notwithstanding the opposition of

Poland's Roman Catholic nobility to many of the terms, the plan, which became

known as the Union of Hadiach, was

approved by the Polish Diet in 1659. The Union of Hadiach

could be viewed as an attempt by a far-sighted political thinker to create a

framework for federation among eastern Europe's warring Christian political

powers: Poland, Lithuania, Muscovy, and the Zaporozhian Host. Conversely, it

could be viewed as yet another attempt by the Cossack elite, the starshyna,

to gain legal entry into the Polish nobility and thereby become part of the

ruling stratum of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. After all, the Union of

Lublin, which in 1569 had created the Commonwealth, was basically the union

or equalization of two dominant estates, the Polish and the Lithuanian

nobility. The proposal at Hadiach was to add a third component, the Ruthenian

nobility of Cossack origin. In this sense, the Union of Hadiach could be

considered another attempt by one segment of Orthodox Ukrainian society to

assure itself of a legally and socially recognized place within the ruling

structure of what was to be known as the Grand Duchy of Ruthenia within a

Polish-Lithuanian-Ruthenian Commonwealth. In the end, the Hadiach proposal

was an ingenious attempt to satisfy the demands of the Cossack starshyna as

well as to achieve peace among the region's warring states. Polish-Lithuanian-Ukrainian-Ruthenian

Commonwealth, as per the Treaty of Hadiach (Click on the map for better

resolution)

The

proposed arms of the Polish-Lithuanian-Ukrainian-Ruthenian Commonwealth Unfortunately for the plan's proponents, the problem of

the semi-independent Zaporozhian Cossacks was not resolved, since at best

only a few of their elite might have been ennobled. Much more difficult to

overcome was the heritage of animosity toward the Poles among broad segments

of Ukraine's population, who still remembered the wars of the Khmel'nyts'kyi

period. Finally, the disenfranchised Zaporozhians distrusted Hetman

Vyhovs'kyi and continued to look toward Muscovy, which in any case was not

about to join the Hadiach confederation. Thus, the Union of Hadiach died a

stillborn death. Despite its failure, Hadiach warrants attention for two

reasons. It was the last attempt to resolve the Ukrainian or Ruthenian

problem as a whole within a Polish frame¬work. Moreover, it was used by later

apologists for Poland as an example of the sup¬posed tolerant nature of the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth. More important, Hadiach revealed how much less interested were

the leading social strata in Ukraine in attaining independence for their

homeland than in retaining or expanding their own social and political

privileges within an existing state. If their own

interests could not be furthered in Poland, then perhaps Muscovy might offer

a better chance. In essence, the whole Period of Ruin in Ukrainian history

can be viewed as a time when the Cossack starshyna continually shifted its

allegiance from Poland to Muscovy and sometimes even to the Ottoman Empire in

a desperate attempt to find a strong ally that would guarantee its leadership

role within Ukrainian society. The starshyna was hampered in its efforts,

however, by two forces: (l) the governments of Poland and Muscovy, each of

which had its own preferences as to how 'peripheral' areas within its realm

should be governed; and (2) the lower-echelon Cossacks from Zaporozhia and

the peasants, who from the outset were opposed to the idea of replacing rule

by a Polish or polonized Ruthenian aristocracy with rule by their 'own,' but

a no less oppressive, Cossack aristocracy. Anarchy,

ruin, and the division of Ukraine During this era of continual civil war and foreign

invasion, the Cossack starshyna had little effective control over events. The

proposed Union of Hadiach, for instance, was viewed by Muscovy as a

declaration of war, and in the spring of 1659 Tsar Aleksei sent an army of

100,000 troops to invade Ukraine. Although the Muscovites were defeated by a

combined Polish-Tatar-Cossack force near Konotop (8 July 1659), Hetman