|

|

The first period of Ukrainian history, or, more

precisely, prehistory, lasted from about 1150 BCE to 850 CE. These twenty-one

centuries of human development on Ukrainian territory witnessed a slow

evolution from primitive agricultural and nomadic civilization to more

advanced societies that attempted to create centrally organized state and

socioeconomic structures. During these millennia, Ukrainian territory was

divided into two rather distinct spheres: (1) the vast steppe and

forest-steppe zones of the hinterland, and (2) the coastal regions of the

Black Sea and Sea of Azov. While in each of

these spheres there were quite different socioeconomic and political

structures, the two were closely linked in a symbiotic relationship based on

a high degree of economic interdependence.

In general,

the hinterland was inhabited by sedentary agriculturalists ruled by different

nomadic military elites who most often originated from the steppes of Central Asia. The Black Sea

coast, on the other hand, was characterized by the establishment of Greek

and, later, Romano-Byzantine cities that either functioned as independent

city-states or joined in federations that had varying degrees of independence

or that were dependent on the Greek, Roman, or Byzantine home- lands to the

south. In effect, the Black Sea coastal cities functioned for over two

millennia as appendages or dependencies, whose economic, social, and cultural

orientation was toward the classical civilizations of the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas.

The

steppe hinterland

The earliest

information about the steppe hinterland and its inhabitants comes from

contemporary Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and Arab writers, who almost invariably

painted negative descriptions of fierce barbarians from the east whose only

purpose in life was to destroy the achievements of the civilized world as

represented by Greece and, later, Rome and the Byzantine Empire. The few

written sources from this early era give a general picture of an unending

swarm of 'barbaric' Asiatic peoples with strange-sounding names such as

Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans, Huns, Avars, Bulgars, and Khazars,

who successively ruled the steppe hinterland before being driven out by the

next nomadic invaders. To be sure, recent archaeological discoveries,

especially during the twentieth century, have revealed that these nomadic

peoples were neither as uncivilized nor as bent on destruction as the

classical Greek and Romano-Byzantine writers made them out to be. In fact,

the civilizations established by these nomads from the east were often

directed to maintaining a stable environment that would allow their income

from trade and commerce to increase.

Before

turning to the chronological evolution during these two millennia (1150 BCE

to 850 CE), a few general caveats should be kept in mind. When considering the

various nomadic groups and their invasions of the Ukrainian steppe, the

reader may form the impression — and misconception — that the fierce warriors

coming from Central Asia belonged to compact

tribes each made up of a particular people. Moreover, it might seem that

these nomads entered territory north of the Black Sea

that was uninhabited, and that a particular tribe remained as the sole

inhabitants until pushed out by another nomadic people, who, in turn, took

their place and began the demographic cycle all over again. Such a scenario

does not reflect what really occurred.

First of all,

the Ukrainian steppe was never virgin uninhabited land into which nomadic

hordes poured. Archaeological evidence has shown that the steppe and, for

that matter, all Ukrainian territories were inhabited throughout the Stone

Age, from its earliest (the Paleolithic, ca. 200,00o-8,000 BCE) to its most

recent (the Neolithic, ca. 5,000-1,800 BCE) stage. The most important change

during these hundreds of millennia occurred at the beginning of the Neolithic

period (ca. 5,000 ME), when the inhabitants of Ukraine changed their means of

livelihood from hunting and mobile food-gathering to the cultivation of

cereals and the raising of livestock. This sedentary and agricultural way of

life continued generally without interruption through the Neolithic or Bronze

Age (ca. 2,500-1,800 BCE), which is also known on Ukrainian territory as the

era of late Trypillian culture.

The end of

the Neolithic or Copper Age was accompanied by a change in the relatively

stable and isolated existence of sedentary communities in Ukraine. This

change took place because during the second millennium BCE, Ukrainian lands

were exposed to the movement of peoples from east-central Europe, to the

arrival of traders from the Aegean and

Oriental lands, and, finally, to the disrupting invasions of steppe peoples

from the east. Nonetheless, both before and during the period 1150 to 850 BCE

there were always fixed settlements throughout Ukrainian territory inhabited

by people who derived their livelihood from agriculture and the raising of

livestock and, secondarily, from hunting and fishing.

The other

misconception about this period concerns the nomadic invaders. Despite the

fact that authors from the Greek and Romano-Byzantine worlds gave names such

as Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, and so on to these groups, none was

ever composed of a culturally or ethnolinguistically unified people. Rather,

these groups were made up of various nomadic tribes that were sometimes

united under the leadership of one tribe that gave its name to (or had its

name adopted by classical authors for) the entire group. Furthermore, after

its arrival in Ukraine,

the sedentary agricultural or pastoral settlers already living there were

also subsumed under the name of the nomadic group that had come to rule over

them. It is in this more complex sense that the names Scythians, Sarmatians,

and Khazars must be understood.

|

|

NOMADIC CIVILIZATIONS ON UKRAINIAN TERRITORY

|

|

|

|

Cimmerians

|

|

1150-750

BCE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scythians

|

|

750-250

BCE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sarmatians

|

|

250

BCE-25o CE

|

|

|

|

Roxolani

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alans

|

|

|

|

|

|

Antes

|

|

|

|

|

|

Goths

|

|

250-375

CE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Huns

|

|

375-550

CE

|

|

|

|

Kutrigurs

|

|

|

|

|

|

Utitrigurs

|

|

|

|

|

|

Avars

|

|

550-565

CE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bulgars

|

|

575-650

CE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Khazars

|

|

650-900

CE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The nomads

of the steppe hinterland

The first of

these nomadic civilizations on Ukrainian territory about which there is

information, albeit limited, was the Cimmerian. The Cimmerians seem to have been

an Indo-European group that came to dominate Ukrainian lands north of the Black Sea between 115o and 950 BCE, a period that

coincides with the late Bronze Age. Most of what we know about the enigmatic

Cimmerians comes from archaeological finds consisting of bronze implements

and the remains of bronze foundries. The Cimmerian era lasted on Ukrainian

territory about four centuries, and it is only from the last two of these

centuries (900-750 BCE) that there exist archaeological remains, of bronze

implements and weapons, along the Black Sea littoral near Kherson (the

Mykhailivka treasure) and from the region just south of Kiev (the Pidhirtsi

treasure).

Around the

middle of the eighth century (750 ME), the Cimmerian era came to end. The

Cimmerian leadership seems to have fled westward (across the Carpathians to Pannonia) and southward (to the Crimea and on to Thrace and Asia

'Minor) in the face of a new invasion of nomads from the east – the

Scythians. The Scythians were known in the classical world for their

fierceness as warriors, but this one-sided image has been tempered by

archaeological discoveries which have unearthed numerous examples of finely

wrought sculpture, ornamentation, and jewellery, primarily in gold. The

Scythians actually formed a branch of the Iranian people – more specifically,

that branch which remained in the so-called original Iranian country east of

the Caspian Sea (present-day Turkestan), as distinct from their Medean and

Persian tribal relatives, who established a sedentary civilization farther

south on the plateaus of Iran.

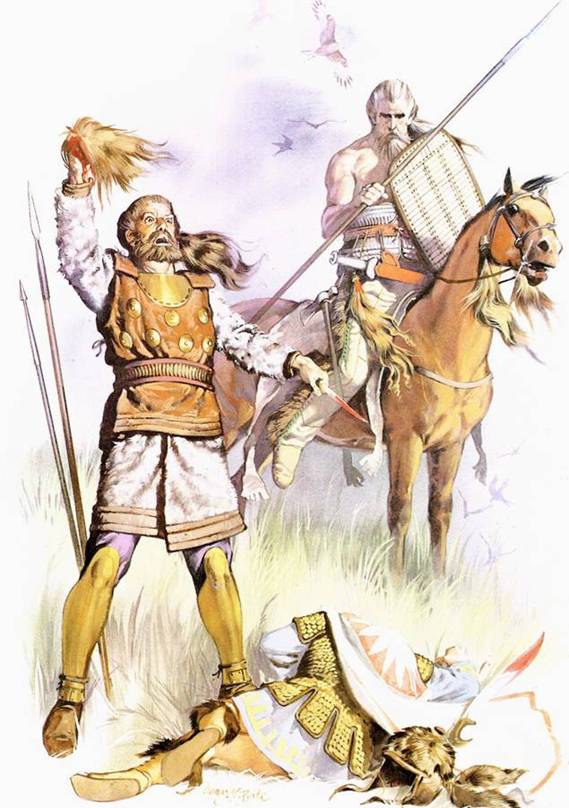

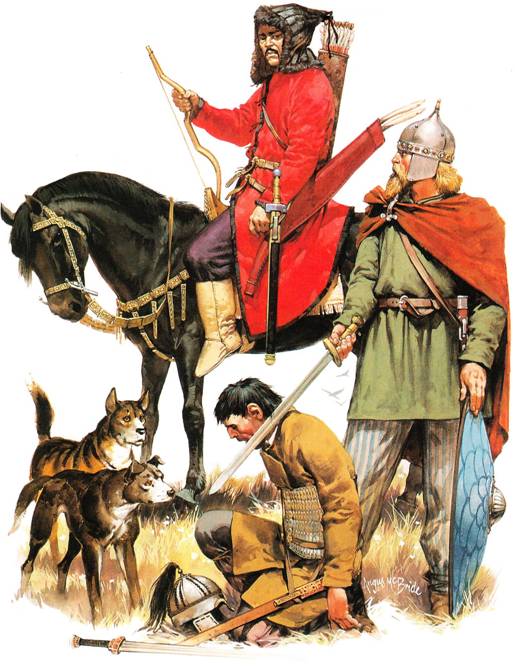

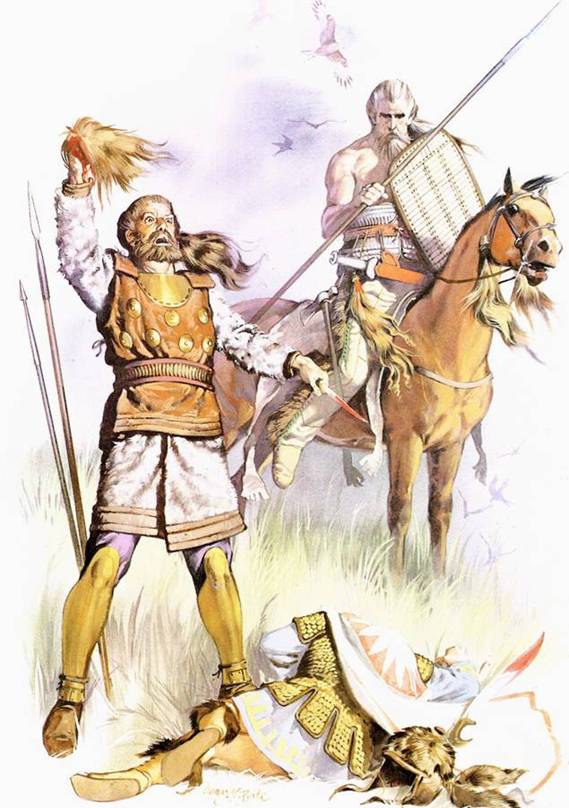

Scythian nobleman / 6th C. BCE

(reconstruction by Angus McBride)

Between 75o

and 700 BCE, the Scythians moved westward toward Ukraine, and eventually they

settled for the most part first in the Kuban Region and Taman Peninsula

(700-550 BCE) and later along the Dnieper River in south-central Ukraine

(550-450 BCE), where their civilization reached its peak between 35o and 250

BCE. Classical sources tell us that Scythian society was composed of four

groups: royalty, notables (steppe nomads), agriculturalists (georgoi), and

ploughmen (aroteres). Actually, only the first two groups – the royalty and

notables – were made up of migrants from the east. This ruling elite, of

nomadic origin and way of life, dominated the sedentary agriculturalists

living under their control and the residents of the cities. Both these

groups, together with their rulers, were known to the outside world as

'Scythians.'

The mention

of cities may seem confusing, since this discussion of the steppe hinterland

has focused so far on nomads and the sedentary agricultural dwellers under

their control. In fact, it seems that the Scythian ruling elite – the royalty

and their notables – virtually lived on horseback, roaming the steppes while

hunting for food or engaging in war with neighboring tribes. One might speak,

however, of mobile Scythian cities, that is, huge caravans of tribes which

moved from one place to another. Nonetheless, there were a few cities – or,

more properly, fortified centers with permanent settlers engaged in activity

other than agriculture – within the Scythian sphere. These were so-called

Oriental-type cities, owned by Scythian royalty and notables and inhabited by

remnants of the Cimmerians and other peoples, who paid tribute to their

Scythian overlords. Among the more important Scythian centers were

Kam"ians'k on the lower Dnieper

River (on the Left Bank opposite Nikopol') and the capital of Scythia Minor, Neapolis, in

the Crimea (north of the mountains, near

present-day Symferopol').

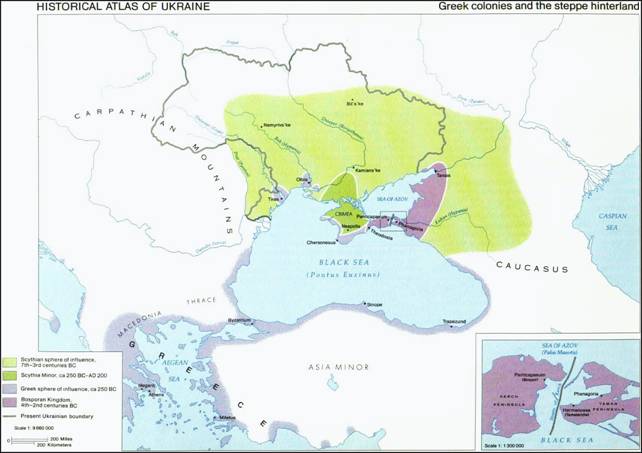

The Greeks of the coastal region

The

few Scythian settlements were in no way as important as the Greek trading

cities along the shores of the Black Sea and Sea of Azov. Not long after the

Scythians began to enter Ukraine

from the east, in the eighth century BCE, colonists fleeing civil strife in Greece arrived from the south, especially from

Miletus, in Asia Minor.

As a result, between the seventh and fifth centuries BCE several prosperous

Greek cities came into being along the shores of the Black Sea, the Straits

of Kerch, and the Sea of Azov. Among the

first to be established were Tiras at the mouth of the Dniester

River and Olbia at the mouth of the

Southern Buh, then Chersonesus at the southwestern tip of the Crimean

Peninsula and Theodosia far-they east on the Crimean

Peninsula, and Panticapaeum (Bospor) and Phanagoria on the west and east

banks respectively of the Straits of Kerch.

The Greek homeland along both shores of the

Aegean Sea was composed of individual

city-states, each of which jealously guarded its independence. By the fifth

century BCE, however, they had come to form a united civilization whose

achievements set a standard for culture in the civilized world that was to

outlast the city-states themselves. Like the Aegean homeland, the Greek

colonies along the northern Black Sea coast at least initially remained

independent of each other, though they were economically and politically

dependent on the city-state

which founded

them – generally either Miletus, along the Aegean coast in Asia Minor, or

Megara, just west of Athens. There were also periods when the Black Sea colonies were completely independent, or when

they united into federations or states.

The most important instance of a federation came into being about 480 BCE,

when the Greek cities near the Straits of Kerch began to unite under the

leadership of Panticapaeum in what became known as the Bosporan Kingdom.

The Bosporan Kingdom became independent of the Greek homeland, and under its

dynamic king Levkon I (reigned ca. 389-348 BCE) came to control all of the

Kerch and Taman Peninsulas as well as the eastern shore of the Sea of Azov as

far as the mouth of the Don River, where the city of Tanais was established

(ca. 375 BCE). The Bosporan Kingdom included not only Greek cities, but also

the regions around the Sea of Azov inhabited by Scythians and related tribes.

Until the second century BCE, the kingdom flourished as a center of grain

trade, fishing, wine making, and small-scale artisan craftsmanship,

especially metalworking. The following century was to witness a period of

political instability and the consequent loss of Bosporan independence.

Finally, in 63 BCE, the Bosporan Kingdom together with other Hellenic states around

the Black Sea came under the control of the Roman Empire.

The Pax Scythica, the Sarmatians, and

the Pax Romano

During the

nearly five centuries from 700 to 250 BCE, the Greek cities along the Black

Sea littoral, in the southern Crimean Peninsula, and in the Bosporan Kingdom

all developed a kind of symbiotic relationship with the Scythian hinterland.

By about 250 BCE, the center of Scythian power had come to be based in the

region known as Scythia Minor (Mala Skifiia), between the lower Dnieper River

and the Black Sea, as well as in the northern portion of the Crimean

Peninsula (beyond the mountains), where the fortified center of Neapolis was

located. The symbiotic relationship had three elements: (1) the Scythian-controlled

Ukrainian steppe, (2) the Black Sea Greek cities, and (3) the Greek

city-states along the Aegean Sea.

Bread and

fish were the staples of ancient Greece, and the increasing demand

for these foodstuffs was met by markets in the Black Sea Greek cities. These

and other food products came from Ukrainian lands, which already in ancient

times had a reputation for natural wealth. In the fourth book of his History,

the Greek historian Herodotus, who had lived for a while in Olbia, wrote the

following description of the Dnieper River, or, as he called it, 'the fourth

of the Scythian rivers, the Borysthenes': 'It has upon its banks the

loveliest and most excellent pasturages for cattle; it contains an abundance

of the most delicious fish; ... the richest harvests spring up along its

course, and where the ground is not sown, the heaviest crops of grass; while

salt forms in great plenty about its mouth without human aid." In this

region, the Scythians exacted grain and fish from the sedentary populations

under their control and traded these commodities in the Greek coastal cities

along with cattle, hides, furs, wax, honey, and slaves. These products were

then processed and sent to Greece.

In turn, the Scythians bought from the Greeks textiles, wines, olive oil, art

works, and other luxury items to satisfy their taste for opulence.

|

|

SCYTHIAN

CUSTOMS

Among the various customs practiced by the Scythians, those associated with

their reputation as fierce warriors made an especially strong impression on

the classical Greek world. In the fourth book of his History, Herodotus

writes:

The Scythian soldier drinks the blood of the first man he overthrows in

battle. Whatever number he slays, he cuts off all their heads, and carries

them to the king; since he is thus entitled to a share of the booty,

whereto he forfeits all claim if he does not produce a head. In order to

strip the skull of its covering, he makes a cut round the head above the

ears, and, laying hold of the scalp, shakes the skull out; then with the

rib of an ox he scrapes the scalp clean of flesh, and softening it by

rubbing between the hands, uses it thenceforth as a napkin. The Scythian is

proud of these scalps, and hangs them from his bridle-rein; the greater the

number of such napkins that a man can show, the more highly is he esteemed

among them. Many make themselves cloaks, like the capotes of our peasants,

by sewing a quantity of these scalps together. Others flay the right arms

of their dead enemies, and make of the skin, which is stripped off with the

nails hanging to it, a covering for their quivers. Now the skin of a man is

thick and glossy, and would in whiteness surpass almost all other hides.

Some even flay the entire body of their enemy, and stretching it upon a

frame carry it about with them wherever they ride.

The skulls of their enemies, not indeed of all, but of those whom they most

detest, they treat as follows. Having sawn off the portion below the

eyebrows, and cleaned out the inside, they cover the outside with leather.

When a man is poor, this is all that he does; but if he is rich, he also

lines the inside with gold: in either case the skull is used as a

drinking-cup. They do the same with the skulls of their own kith and kin if

they have been at feud with them, and have vanquished them in the presence

of the king. When strangers whom they deem of any account come to visit

them, these skulls are handed round, and the host tells how that these were

his relations who made war upon him, and how that he got the better of

them; all this being looked upon as proof of bravery.

SOURCE: Herodotus, The History, translated by George Rawlinson, Great Books

of the Western World, Vol. VI (Chicago, London, and Toronto 1952), pp.

134-135•

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As a result

of these economic interrelations, the Greeks brought to the world the earliest

and still the primary information about the Scythians. Herodotus, in

particular, left a detailed description of the geography, way of life, and

often cruel customs of the Scythians and of the lands under their control.

The other source of information about the Scythians, which corroborates much

of what Herodotus %%rote, is their numerous burial mounds, spread throughout

south-central Ukraine

and excavated in modern times. These burial mounds (known as kurhany, or

barrows) have preserved for posterity that for which the Scythians are most

famous: their small-scale decorative art, which consisted primarily of finely

balanced renderings of a host of animal forms in gold and bronze. It is not

certain whether this art was produced by the Scythians for themselves, or,

more likely, commissioned from Greek artisans living in the cities.

Nevertheless, its themes reflect the violence of the world the Scythians

inhabited, and its forms show the high level of technology their civilization

was able to foster and appreciate.

Scythian warriors

/ 4th C. BCE (reconstruction by Angus McBride)

Notwithstanding

the cruelty to human and non-human animals depicted in their art, the

Scythians brought a period of peace and stability to Ukrainian territories

which lasted for about 500 years and which has come to be known as the Pax

Scythica, or Scythian Peace. During the Pax Scythica, the Scythians promoted

trade and commerce with the Greek cities along the Black Sea, which in turn

supplied Greece

with needed foodstuffs and raw materials. The Scythians also successfully

fought off other nomadic peoples from the east, and they even defeated the

great Persian king Darius I (reigned 522-486 BCE). Darius attempted to

conquer the Scythians and to persianize their land, which he considered to be

'outer Iran'

and part of his own patrimony. His efforts against the Scythians were

unsuccessful, but the incursion of Darius in 513 BCE became the first major

historical event involving Ukrainian territory recorded in written documents.

It would be

some time before long-term stability like that created by the Pax Scythica

was reestablished in Ukraine.

Around 250 BCE, nomads related to the Scythians and known as Sarmatians

appeared in the Ukrainian steppe. The Sarmatians were typical of the

civilizations under discussion in that they were not a homogeneous people,

but rather made up of several tribes, each of which led an independent

existence. Those most directly associated with developments in Ukraine were

the Roxolam and, in particular, the Alans.

At least

during the first two centuries of the Sarmatian presence, that is, from 250

to 50 BCE, the relative stability and resultant economic prosperity that had previously

existed between the Scythian hinterland and the Greek cities of the coast was

disrupted. Pressed by the Sarmatians in the steppe, the Scythian leaders fled

to the Crimea, where they were forced to consolidate their rule over a

smaller region that included the Crimean

Peninsula north of the mountains and

the lands just to the north between the peninsula and the lower Dnieper River. This new political entity,

which, with its capital at Neapolis, was known as Scythia Minor (Mala

Skifiia), lasted from about 250 BCE to 200 CE. Initially, the Scythian

leadership in Neapolis tried to continue its traditional practice of exacting

tribute and goods from the Greeks. But because they no longer controlled the

resources of the steppes, they had nothing to give the Greeks in return. The

result was frequent conflict between the Scythians of the Crimea and the

Greek cities along the coast and in the Bosporan Kingdom.

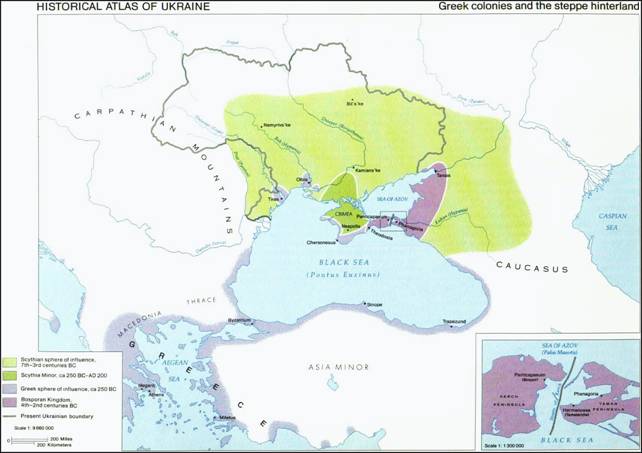

Click on the map for better resolution

This era of

instability, which affected not only the Sarmatian-controlled hinterland but

also the Black Sea cities, came to an end

along the coastal region after 63 BCE. Beginning in that year, the Roman Empire

succeeded in extending its sphere of influence over the independent Greek

cities as well as over those within the Bosporan Kingdom.

With the presence of Roman legions and administrators in the region, peace

and stability were restored. The new Pax Romana reduced the friction between

the Scythians and the Greeks in the Crimea,

and the Sarmatian tribes in the hinterland also realized the advantages to be

accrued from some kind of cooperation with the Roman world. Reacting to the

stabilizing presence of the Romans, one Sarmatian tribe, the Alans, renewed

the Scythian tradition of trade with the Greco-Roman cities. Before long, a

Greek-Scythian-Sarmatian hybrid civilization evolved within the Bosporan Kingdom,

which itself was revived, this time under the protection of Rome. The resultant trade and commerce

between the steppe hinterland and the Mediterranean world brought a renewed

prosperity to the Bosporan

Kingdom that lasted for

over two centuries.

The third century CE, however, ushered in a

new era of instability, especially in the steppe hinterland, that was to last

until the seventh century. During these four centuries, Ukrainian territory

was subjected to the invasions of several new nomadic warrior tribes who were

bent on destruction and plunder of the classical world as represented by the Black Sea and Bosporan coastal cities. With few

exceptions, the nomads were not interested – as the Scythians and even the

Sarmatians had been before them – in settling down and exploiting by peaceful

means the symbiotic relationship of the steppe hinterland and coastal cities.

Between about 250 and 650 CE, several nomadic groups – the Goths, Huns,

Kutrigurs, Utrigurs, Avars, Bulgars – came and went across parts of Ukrainian

territory. It was not until the arrival of the Khazars in the seventh century

that stability was restored north of the Black Sea.

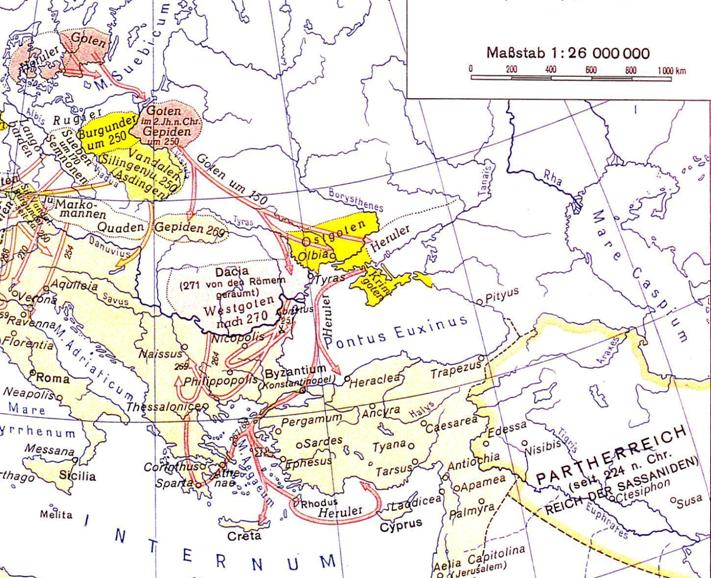

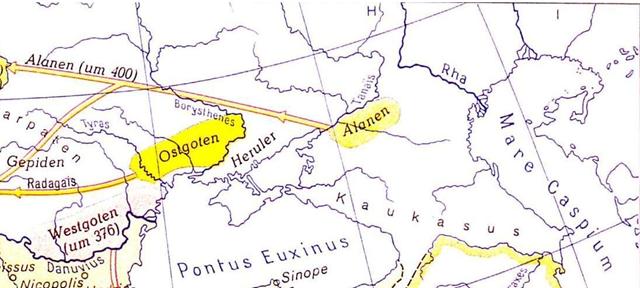

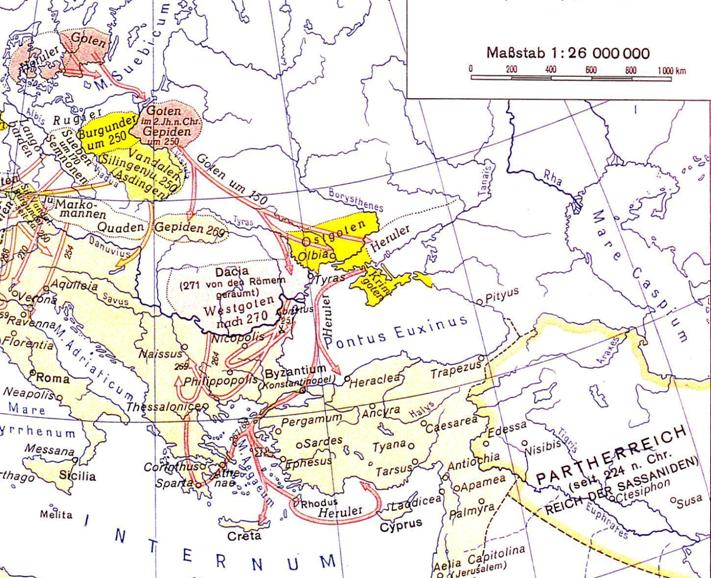

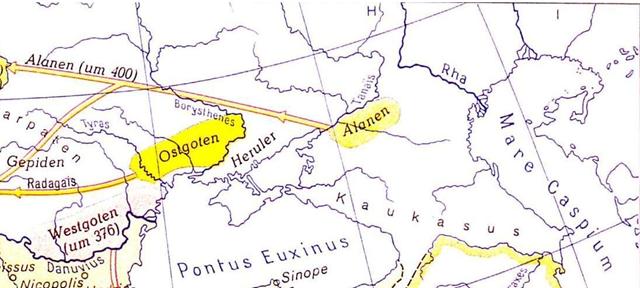

German map showing migration of the Goths into and

through the Ukraine in the 2nd and 3d centuries CE

The four

centuries of strife between 250 and 650 CE began not with the arrival of

nomads from Central Asia in the east, but

rather with the arrival in the early third century of Germanic tribes known

as Goths from the northwest. Originally from Sweden

and living in what is now Poland,

the Goths moved south into Ukraine,

where they broke the Sarmatian dominance of the hinterland. After 250 CE,

they captured Olbia and Tiras from the Romans, with the result that during

the following century the remaining Greco-Roman cities as well as the Bosporan Kingdom came under Gothic domination.

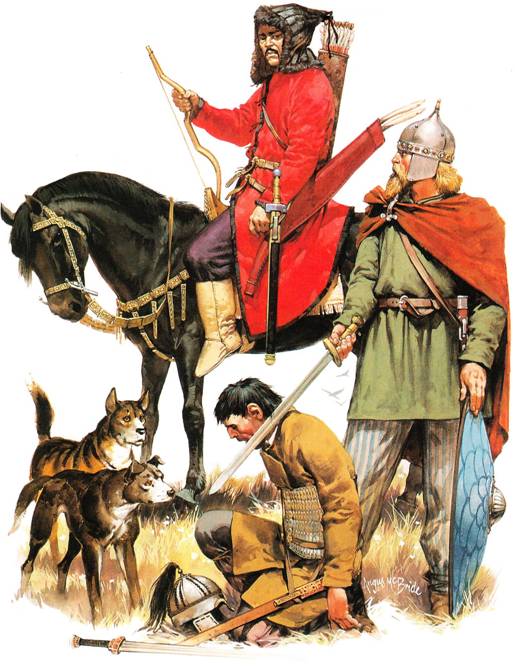

Mounted Hun and

Goth warrior with a captured Bosporan soldier (reconstruction by Angus

McBride)

German map showing migration of the Alans through the

Ukraine in early 5th century CE

One branch of

the Goths, the Ostrogoths or East Goths, eventually focused their control on

the Crimean Peninsula

and the remnants of the Bosporan

Kingdom, which still

had potential wealth, to be derived from trade and local artisan works.

Ostrogoth rule reached its apogee during the late fourth century under the

king Hermanaric (reigned 350-375). Anxious to maintain good relations with

the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire to the south, the Ostrogoths even

accepted Christianity. In about 400 CE, they received a bishop, the first in

a line of ecclesiastics who were to ensure the presence of Christianity among

the Ostrogoths for several centuries to come. From their mountain stronghold

at Doros, in the Crimean Peninsula (just 12 miles [2o kilometers] east of

Chersonesus), the Ostrogoths, or, as they came to be known, the Crimean

Goths, functioned during the next four centuries as a protective shield for

the Greco-Byzantine cities along the coast against further invasions by

nomads from the north.

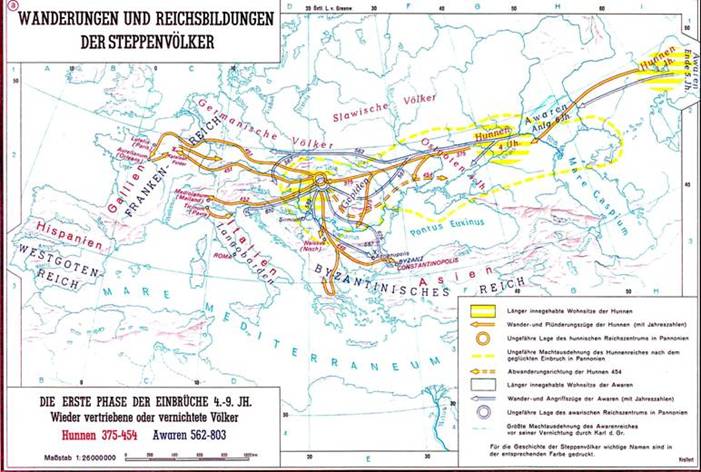

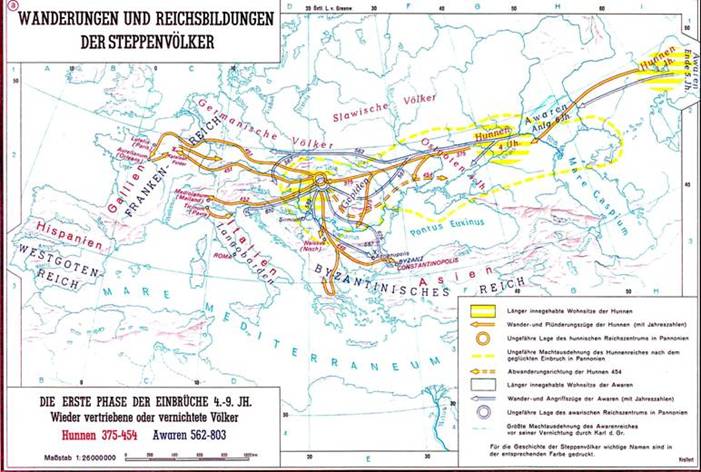

German map showing migration of the Huns (375-454) and

Avars (562-803) into and through the Ukraine

(Click on the map for higher resolution)

Meanwhile,

the Ukrainian hinterland north of the Crimean

Peninsula and Black

Sea was subjected to a series of invaders: the Huns in the late

fourth century, the Kutrigurs and Utrigurs in the fifth century, the Avars in

the sixth century, and the Bulgars in the seventh century. More often than not,

the presence of these groups in Ukraine was short-lived. This was

because they were in search of the richer sources of booty to be found along

the borders of the Roman Empire in central Europe (the Pannonian Plain) or

along the trade routes between the Black and Caspian Seas.

During periods when one nomadic group had departed and another not yet

arrived, the power vacuum was sometimes filled by the local population. One

such case was that of the Antes, a tribe of Sarmatian (Alanic) and possibly

Gothic elements which by the third century had organized the sedentary

agricultural population of south-central and southwestern Ukraine into a

powerful military force that stood up to the Goths, the Byzantine Empire, and

the Huns. Because this sedentary population, which the Antes led and to which

they gave their name, was probably composed of Slays, the group is of

particular interest with respect to subsequent developments in Ukraine

(see chapter 4).

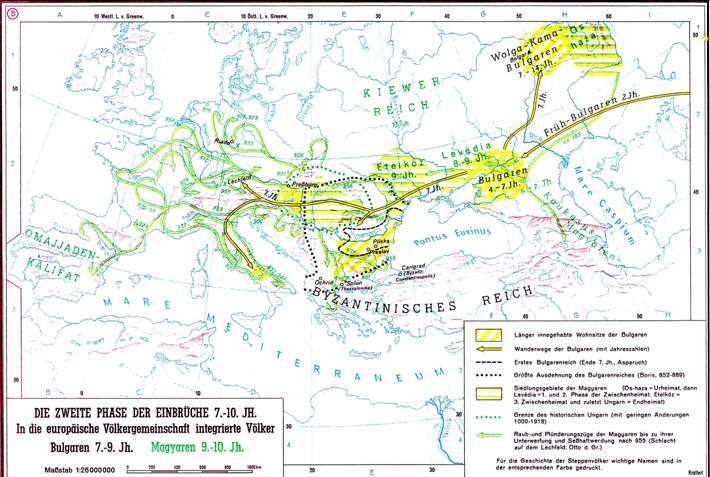

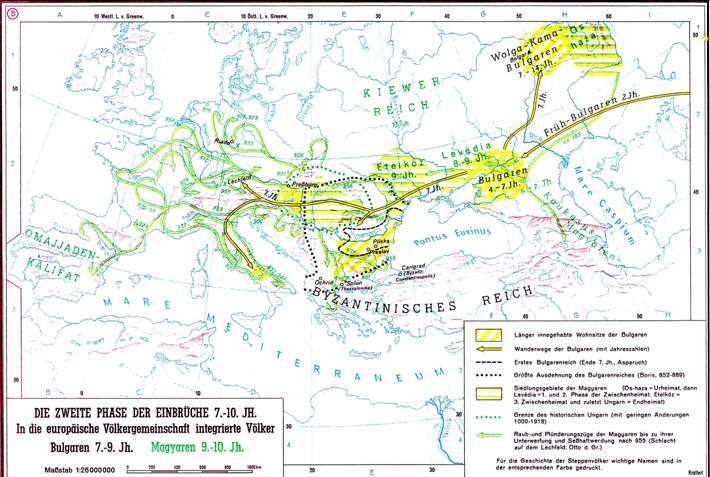

German map showing migration of the Bulgars (7th

– 9th centuries) and Kutrigurs / Utrigurs (9th century)

into and through the Ukraine

(Click on the map for higher resolution)

The

Byzantines and the Khazars

While the

Ukrainian steppe and hinterland were experiencing frequent disruptions

between 25o and 650 CE, the coastal region along the Black Sea and Sea of Azov was undergoing another revival. This time the

stabilizing factor was the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire, which reached

its greatest territorial extent and political influence during the

sixth-century reign of Emperor Justinian (reigned 527-565). Under Justinian,

the Black Sea coastal cities received

Byzantine garrisons, their walls were fortified, and Chersonesus, on the

western tip of the peninsula, became the region's Byzantine administrative

center. Byzantine Greek culture in the form of Eastern Christianity also was

strengthened, with the result that Chersonesus, with its ten churches and

chapels (including St Peter's basilica in Kruze) and a monastery built in a

cave along cliffs at nearby Inkerman, was to become an important center from

which Christian influence was subsequently to radiate throughout Ukrainian

territory and among the East Slays. Byzantine influence was also strong at

the eastern end of the Crimea, where the Bosporan

Kingdom was revived, this time as a

colony of Byzantium.

While it is

true that direct Byzantine political control over the Crimean cities and the Bosporan Kingdom was frequently interrupted,

economic, social, and cultural ties in the form of Byzantine Orthodox

Christianity were to last until at least the thirteenth century. It was

during the era of Roman and Byzantine control of the Bosporan Kingdom,

moreover, that Hellenic Jews settled in the region's coastal cities. And it

is from these cities that Jewish contacts across the Straits of Kerch were,

by the seventh century, to reach a new nomadic civilization that was

beginning to make its presence felt.

Not

long after the rise of Byzantine influence along the coast, which began in

earnest during the late sixth century, a group of nomads arrived from the

east whose presence was to have a profound impact on the region north and

east of the Black Sea. These were the

Khazars, a Turkic group who originally inhabited the westernmost part of the

Central Asiatic Tyirkyit Empire. Unlike most of their predecessors during the

preceding three centuries, the Khazars preferred diplomacy to war. Soon after

their arrival along the Black Sea, they signed a treaty (626) with the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines, ever anxious about

their own eastern frontier with the Persians and about potential invaders

from the east who might threaten their Black Sea possessions, welcomed the

seeming willingness of the Khazars to fit into the plans of Byzantium's northern diplomacy.

The

appearance of the Khazars in the seventh century proved to be of great

significance for developments in eastern Europe in general and in Ukraine in

particular. The Khazars continued the tradition established by the Scythians

(750250 BCE) and continued by the Sarmatians (50 BCE to 250 CE) whereby

nomads from the east would gain control over the sedentary population of the

steppe hinterland, keep in line recalcitrant nomadic tribes, protect trade

routes, and foster commercial contacts with the Greco-Roman–Byzantine cities

along the Black Sea coast. The age-old symbiotic relationship between the

coast and the steppe hinterland was to be restored under the hegemony of the

Khazars. The resultant Khazar peace, or Pax Chazarica, which lasted

approximately from the mid-seventh to the mid-ninth century, did in fact

cushion the territory from further nomadic invasions from the steppes of

Central Asia in the east as well as from incursions by the Persians and,

later, the Arabs from the south. Because of the Khazars' role in protecting

the eastern and southern frontiers of the European continent, some writers

have compared them to Charles Martel and the Franks in western Europe. The

Pax Chazarica also provided two centuries of peace and stability during which

sedentary peoples living within the Khazar sphere of influence were allowed

to develop. Among those peoples, within and just beyond the northwestern edge

of the Khazar sphere, were the Slavs.

|

|