|

|

THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA AND DNIEPER

UKRAINE’S OTHER PEOPLES Paul Robert Magocsi Excerpts from Chapter 38 from the book ”History of Ukraine”, Toronto / 1996 |

||

|

|

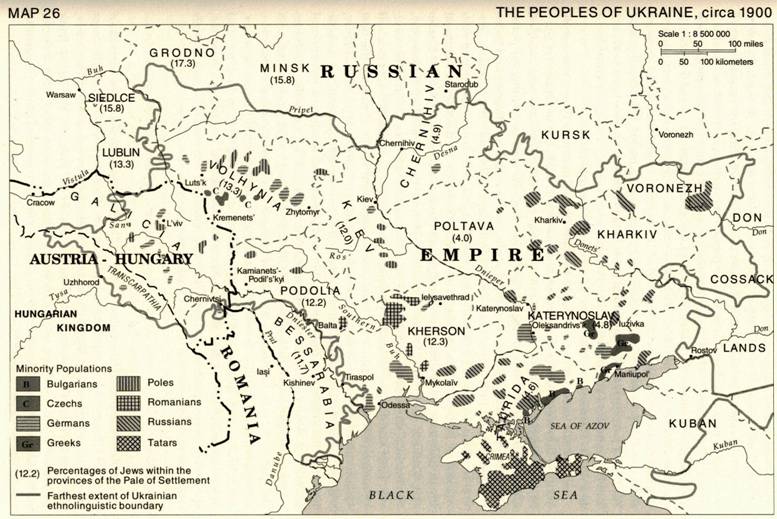

Click on the map for better resolution Aware of such negative attitudes toward

Ukrainian political aspirations, in 1917 the Central Rada

implemented liberal policies and set up the Secretariat for Nationality

Affairs in an attempt to attract support from Dnieper Ukraine's other

peoples. Adopting the nationality theories advocated by the Austrian

socialists Otto Bauer and Karl Renner, the Central Rada

enacted a law in January 1918 that provided for national-personal autonomy.

National-personal, or national-cultural, autonomy meant that an individual

was guaranteed certain rights with a view to the protection of his or her

language and culture regardless of place of residence. This autonomy was

different in kind from territorial autonomy, in which a specifically defined

area was granted autonomous status. Among the rights guaranteed by

national-personal autonomy were schools, cultural

institutions, and religious societies. All would receive financial support

from the central government, which in turn would establish tax revenues

according to a fiscal plan devised by the nationalities themselves.

Interestingly, only Jews, Russians, and Poles were singled out as eligible

for national-personal autonomy; seven other groups (Belarusans,

Czechs, Romanians, Germans, Tatars, Greeks, and Bulgarians) would first have

to petition for and receive governmental approval in order to obtain

autonomous status. Jews, Russians, and Poles were each given their own

ministries and guaran-teed a certain number of

seats in the Central Rada and Little Rada. The Jews had fifty deputies in the Central Rada (equally divided among five Jewish political

parties) and five deputies in the Little Rada. Jews

also received posts in the General Secretariat and, later, the ministerial

council of the Ukrainian National Republic, in which the Ministry of Jewish

Affairs was created (headed at various times by Moshe Zilberfarb,

Wolf Latsky-Bertholdi, Avraham

Revutsky, and Pinkhes Krasny). Yiddish was made an official language (it even

appeared on some of the Ukrainian National Republic's paper money); Jewish

schools and a department of Jewish language and literature at the university

in Kam"ianets'-Podil's'kyi were established;

and plans were made to revive the historic Jewish self-governing communities

(the kahals) that had been abolished by the tsarist

government in 1844. Of Jewish political parties, the socialists were the

first to cooperate with the Central Rada, and

others, including the Zionists, eventually followed. All Jewish parties,

however, strongly opposed the idea of an independent Ukraine and either

abstained from voting on or voted against the Fourth Universal.

Moshe Zilberfarb The promising atmosphere in

Jewish-Ukrainian relations created by the Central Rada

during the first phase of Dnieper Ukraine's revolutionary era changed during

the Hetmanate of the second phase and then

dissolved completely during the anarchy and civil war of the third phase

(1919-1920). Hetman Skoropads'kyi's government

effectively ended the experiment in Jewish autonomy, but it at least

maintained social stability in the cities and part of the countryside. During

the third phase of the revolutionary era, maintaining such stability proved

well beyond the powers of the Directory, faced as it was with foreign

invasion, civil war, and peasant uprisings. Even though the Ministry of

Jewish Affairs was revived and Jewish autonomy theoretically restored, this

meant little to Dnieper Ukraine's Jews, who faced a wave of pogroms and

so-called excesses (less violent attacks in which there was usually no loss

of life) that intensified after May 1919. Of the 1,236 pogroms in 524

localities recorded between 1917 and early 1921 in Dnieper Ukraine, six

percent occurred before 1919, and the rest after. Estimates of the number of

persons killed in the pogroms during the entire period range from 30,000 to

60,000. Whether the pogroms and excesses were carried out by White Russian

armies, by forces loyal to the Bolsheviks or to the Ukrainian National Republic,

or by uncontrolled marauding bands and self-styled military chieftains (like Hryhoriiv and Makhno), the

Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic and particularly its leader, Symon Petliura, have been

blamed in most subsequent Jewish writings. The pogroms have so clouded the

historical record that authoritative sources like the Encyclopedia Judaica have concluded that no Ukrainian government,

neither the Central Rada, nor the Hetmanate, nor the Directory, was ever sincere about

Jewish autonomy or about 'really developing a new positive attitude toward

the Jews.' Whoever or whatever is responsible for the pogroms of 1919—1920 in

Dnieper Ukraine, there is no question that their occurrence poisoned

Jewish-Ukrainian relations for decades to come both in the homeland and in

the diaspora. The Russian minority in Dnieper Ukraine

invariably opposed the idea of separation from Russia. This applied across

the political spectrum, from the left-wing Bolsheviks, who actually made up

the majority of the members in the Communist party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine, to

the right-wing monarchists, known as the Bloc of Non-Partisan Russians and

represented by the ukrainophobic Russian-language

daily newspaper Kievlianin (Kiev, 1864-1919),

edited by Vasilii Shul'gin.

When, in July 1917, the Central Rada was opened to

national minorities, the Russians had fifty-four deputies. There were also

eight Russians in the Little Rada and two ministers

(Aleksandr Zarubin for

postal services and Dmitrii Odinets

for Russian affairs) in the General Secretariat. As the Central Rada moved increasingly toward autonomy and then

independence for Ukraine, however, the Russian deputies began leaving the

assembly until only four Socialist-Revolutionaries and the minis-ter Odinets remained. With the establishment

of the Hetmanate in April 1918, the majority of

Russians, especially from the center and right side of the political spec-trum, supported the new Ukrainian government. These same

groups also welcomed the efforts of General Denikin's

Volunteer Army to restore Russian control over Ukraine in 1919.

Vasilii Shul'gin The Russians' attitude toward Ukrainian

aspirations is not surprising. From their perspective, they lived in Little

Russia, which for them was an inalienable part of the Russian homeland. As

for Ukrainianism, most Russians considered it

little more than a political idea concocted by a few misguided intellectuals

or a by-product of the anti-Russian designs of foreign powers, especially

Austria-Hungary and Germany. According to such a scenario, the peasant masses

were not Ukrainians, they were Little Russians. It was simply inconceivable

to Russians (or, for that matter, russified

Ukrainians) imbued with such attitudes that their beloved Little Russian

homeland could ever be torn from mother Russia and transformed into an

'artificial' independent Ukrainian state. Poles living in Dnieper Ukraine exhibited

mixed reactions to the events that engulfed them during the revolutionary

era. It was actually owing to World War I that the number of Poles in Dnieper

Ukraine increased. This was the result of large numbers having fled eastward

from the Congress Kingdom, the Russian Empire's far-western Polish-inhabited

entity, which for extensive periods of time was held by the Central Powers.

Cities on the Right Bank received many Poles during this influx; their number

in Kiev, for instance, reached 43,000, or 9.5 percent of the inhabitants, in

1917. Following the February Revolution in the

Russian Empire, the Poles in Dnieper Ukraine organized themselves essentially

into two groups. The Polish Executive Committee in Rus'

(Polski Komitet Wykonawczy na Rusi), led by Joachim Bartoszewicz,

primarily represented the landowning class and conservative National

Democrats, who were sympathetic to the Polish liberation movement. The Polish

Democratic Center party, headed by Mieczyslaw

Mickiewicz, Roman Knoll, and Stanislaw Stempowski,

represented more liberal political trends, although it too supported the

interests of Polish landowners and shared their inclination for an

independent Polish state. Leaders of the Polish Democratic Center party took

advantage of the Central Rada's invitation to

participate in its administration, and it obtained places for twenty deputies

in the Central Rada and two in the Little Rada. Then, following the Fourth Universal in January

1918, the Ministry for Polish Affairs headed by Mickiewicz was created as

part of the ministerial council of the Ukrainian National Republic.

Joachim Bartoszewicz The Ministry for Polish Affairs ceased to

exist following the fall of the Central Rada in

April 1918. The Hetmanate cooperated instead with the

Polish Executive Committee, which welcomed the conservative intention of the Hetmanate government to restore the large landed estates.

The days of the Polish landlords and their hold over the Right Bank

countryside were numbered, however. In response to the peasant revolts and

anarchic conditions which dominated the 1919-1920 period,

and following the establishment of Soviet rule in Dnieper Ukraine, large

numbers of Poles fled westward to the new Polish state. Consequently, the

number of Poles remaining in Dnieper Ukraine decreased by at least one-third,

from 685,000 in 1909 to 410,000 in 1926. The only sizable national minority entirely

to avoid dealings with the Central Rada or with

other non-Bolshevik governments in Dnieper Ukraine were the Germans. Maintaining

the aloofness that had characterized them since tsarist times, the Germans

remained in their rural communities and tried to keep as uninvolved as

possible with both the Ukrainians and the Russians in their midst and in the

urban centers. Because of the all-encompassing changes and cataclysmic events

of the revolutionary era, however, the Germans were unable to remain

unaffected for long. In relative terms, they perhaps suffered the most of all

Dnieper Ukraine's peoples. Already during World War I, the Germans

living in Volhynia and in the Chelm

region, that is, in areas closest to the front, had been deported, in 1915,

by the tsarist Russian government, primarily to Siberia. They were suspect in

the eyes of Russian officialdom, who feared their collaborating with the

advancing German Army. Then, during 1919 and the height of the peasant leader

Makhno's military ravages, many German villages,

especially in Katerynoslav province, were attacked

in destructive pogroms. Their inhabitants either were killed or, if they

managed to escape, eventually reached Germany or the United States. The

pacifist Mennonites and their prosperous rural farms proved especially easy

targets for Makhno's anarchist bands. As a result

of the World War I deportations and the destruction wrought during the

revolutionary era, the number of Germans in Dnieper Ukraine decreased by

almost two-fifths, from 750,000 in 1914 to 514,000 in 1926. The Tatars were different from other

peoples in Dnieper Ukraine in that they inhabited the Crimea, a territory

claimed by the Hetmanate, but in which no Ukrainian

government had any authority during the revolutionary era. Under tsarist

rule, the Tatars suffered cultural discrimination and the persecution of

their national leaders, many of whom were forced to flee abroad, especially

across the Black Sea to the Ottoman capital, Istanbul. There they set up

conspiratorial nationalist organizations, the most important being Vatan, whose goal was independence for the Crimea. Following the February Revolution of 1917,

several Tatar nationalist leaders returned from exile and in April joined

with their Crimean fellows in forming the Muslim Executive Committee. Led by

the recently returned nationalists Noman Celebi Cihan and Cafer Seidahmet Kirimer, the Committee demanded cultural autonomy for the

Tatars. By May, that demand had changed to territorial autonomy, and in July

a Crimean Tatar Nationalist party (Milli Farka) was established to work toward the restructuring

of the Russian Empire on a federal basis. Somewhat in the manner of the

Ukrainian Central Rada, which was meeting at the

same time in Kiev, the Crimean Tatars gradually broadened their goal from

autonomy to complete independence. This process culminated in December 1917

with the creation of a constituent assembly (Kurultai)

in Bakhchesarai with its own government, headed by Noman Celebi Cihan. Throughout 1917, the Crimean leadership

maintained cordial relations with the Central Rada,

which supported the Tatar demands for territorial and cultural autonomy. The

Russians and Ukrainians living in the Crimea, however, were opposed to

Crimean Tatar nationalist activity. It is also interesting to note that the

Crimean Tatars encountered strong opposition from other Turkic groups in the

Russian Empire, especially from the Volga and Ural Tatars. Following the

Bolshevik accession to power in November 1917, Bolshevik-dominated soviets

became an important politicapl factor in the

Crimea, especially in the seaport city of Sevastopol'. The soviets, too,

expressed firm opposition to the goals of the Tatar nationalists. In January 1918, the Bolsheviks drove the

recently created Tatar constituent assembly out of Bakhchesarai

and set up a Soviet government. But it survived only until May, when German

troops from Dnieper Ukraine arrived in the peninsula. Although the Germans

had driven out the Bolsheviks, they refused to recognize the Tatar

nationalists. Instead, they appointed a Muslim military official (actually a

Lithuanian Tatar, Sulkevich) who served German interests.

Following the departure of the Germans from Dnieper Ukraine in late 1918, the

Crimea was ruled successively by a pro-Russian liberal government (under the

Crimean Karaite leader of the Kadet

party, Solomon S. Krym), until April 1919; a Soviet

Crimean Republic in cooperation with the Crimean Tatar National party, until

June 1919; and White Russian armies under General Denikin

and his successor, Petr Vrangel',

who had retreated to the Crimea from the advancing Soviet Red Army.

Solomon S. Krym When, in October 1920, the Whites were

finally driven out of their last European stronghold, the Crimea, the

Bolsheviks returned to the peninsula for the third and final time. They

immediately branded their estwhile allies, the

Crimean Tatar National party (Milli Farka), as counterrevolutionary and declared their own

subordination to the Soviet government in Moscow. A year later, in October

1921, Moscow created the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which

became an integral part of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic.

Thus, by the fall of 1920, Dnieper Ukraine and the Crimea were both within

the Soviet orbit ruled from Moscow.

Petliura and the Pogroms

The

time has come to realize that the peaceable Jewish population — their women

and children - like ours have been imprisoned and deprived of their national

liberty. They [the Jews] are not going anywhere but are remaining with us, as

they have for centuries, sharing in both our happiness and our grief. The

chivalrous troops who bring equality and liberty to all the nationalities of

Ukraine must not listen to those invaders and provocators

who hunger for human blood. Yet at the same time they cannot remain

indifferent in the face of the tragic fate of the Jews. He who becomes an

accomplice to such crimes is a traitor and an enemy of out

country and must be placed beyond the pale of human society. ... ... I

expressly order you to drive away with your forces all who incite you to

pogroms and to bring the perpetrators before the courts as enemies of the

fatherland. Let the courts judge them for their acts and not excuse those

found guilty from the most severe penalties of the law.* The excerpt above is from an order by Petliura issued on 26 August 1919 to the troops of the

Ukrainian National Republic. Despite this and other actions taken by him

earlier in the year to assist the Jewish population, the relationship of Petliura to the pogroms of 1919 has remained a

controversial issue. Subsequent literature on the subject differs greatly,

according to whether the authors are of Jewish or Ukrainian background. The

following are examples of the often extreme difference of opinion about Petliura.

Simon Petliura In 1976, the Jewish writer Saul S. Friedman

published a book about the assassination of Petliura

with the provocative title Pogvmchik, which

concludes with ten reasons why Petliura was 'responsible

for the pogroms.' Among them are the following: 1. Simon Petlura was Chief of

State, Ataman-in-Chief, with real power to act when he so desired. No

Ukrainian leader enjoyed comparable respect, allegiance or authority. 2. Units of the Ukrainian Army directly under his

supervision (the Clans of Death) committed numerous atrocities. Instead of

being punished, the leaders of these units (Oudovichenko,

Palienko, Angel, Patrov, Shandruk) received promotions. 3. Insurgents dependent upon Petlura

for financial support and war material committed pogroms in his name. Petlura maintained a special office to coordinate the

activities of these partisans. Rather than punishing them, he received their

leaders with honors in his capital. 4. There is good reason to believe that Petlura may have ordered pogroms in Proskurov

and Zhitomir in the early months of 1919, and that the Holovni

Ataman [Petliura] was in the immediate vicinity of

these towns when pogroms were raging. Yet he did nothing to intervene

personally; nor did he command the expeditious punishment of the major pogromchiks. 5. Petlura's famous orders of August 26 and 27, 1919, forbidding

pogroms, were issued eight months too late, at a time when the Holovni Ataman had no real power. They were designed

specifically for foreign consumption. 6.

What funds were

authorized for the relief of pogrom victims were a trifle compared with how

much was needed and how much had been stolen from the Jews. Like Petlura's famed orders, they were too little and too late.* In 1969-1970, the American scholarly

journal Jewish Social Studies published a debate about Petliura

and the Jews during the revolutionary years. The Ukrainian-American historian

Taras Hunczak came to the following conclusions: The

frequently repeated charge that Petliura was antisemitic is absurd. Vladimir Jabotinsky,

perhaps one of the greatest Jews of the twentieth century - a man well-versed

in the problems of East European Jewry - categorically rejected the idea of Petliura's animosity towards the Jews. ... Equally

absurd is the attempt on the part of some to establish Petliura's

complicity in the pogroms against Ukrainian Jewry. Particularly disturbing is

the

recent attempt by Hannah Arendt to draw a parallel between the case of Petliura and Adolf Eichmann, Hitler's notorious henchman. In

view of the evidence presented, to convict Petliura

for the tragedy that befell Ukrainian Jewry is to condemn an innocent man and

to distort the record of Ukrainian-Jewish relations.* * Pavlo Khrystiuk, Zamitky i materiialy do istorii ukrains'koirevolutsi'i,

1917—1920 rr., Vol. IV (Vienna 1922), pp. 167-168. * Saul S. Friedman, Pogromchik

(New York 1976), pp. 372-373 'Taras Hunczak,

'A Reappraisal of Symon Petliura

and Jewish-Ukrainian Relations, 1917-1921,' Jewish Social Studies, XXXI (New

York 1969), pp. 182-183. Mennonites Caught in the Revolution The reaction of Ukraine's indigenous

German, in particular Mennonite, inhabitants to the revolution and civil war

is summed up by Dietrich Neufeld in a diary-like memoir from 1919-1920 later

published under the title A Russian Dance of Death (1977). Of particular

interest in the book are the Mennonites' perceptions of their own place in

the former Russian Empire, of the anarchist leader Makhno,

of their Ukrainian neighbors, whom they refer to as Russians, and finally -

because they are pacifists - of the difficult decision to take up arms in

self-defense.

Nestopr Makhno Even

these peaceful Mennonite settlers who up till now have remained aloof from

all history-making events are caught up in the general upheaval. They no

longer enjoy the peace which dominated their steppe for so long. They are no

longer permitted to live in seclusion from the world. Makhno. Who

doesn't quake at that name? It is a name that will be remembered for

generations as that of an inhuman monster. ... His professed aim is to put

all 'capitalists' to the sword. Even the Bolsheviks - dedicated to the same

cause but more sparing of human life on principle - are too tame for him. His

path is literally drenched with blood. Presumably,

the Makhnovites despoiled our people because of

their alleged sym-pathy for Denikin.

It can't be denied that our colonists, though professing neutrality, do not

show much sympathy for the peasants. While the peasants opposed the

re-establishment of the old regime, the [Mennonite] colonists remained loyal

to that cause. They even allowed themselves to be enlisted in Denikin's army. Actually, they were tricked into doing so

by being assured that they would be organized into local Self Defence units

only. Many

of our young men, who as a consequence of the German occupation had developed

distinctly anti-Russian attitudes, were eager to avenge the looting and

suffering inflicted on our people [in 1918, before the German troops

arrived]. ... They supported the German army of occupation and, in some

cases, had been foolish enough to inform against certain of the revolutionary

leaders. One

can criticize the Zagradovka Mennonites for taking

up arms instead of hold-ing fast to the principle

of non-resistance. As good Christians they had no right to show hatred toward

their neighbor. Their duty was to love him even when he wronged them.

Instead, they made common cause with a soldiery which plundered and murdered

- even though we have no reason to supect any young

Mennonites of a similar lack of restraint.... The Zagradovka Mennonites took up arms without hesitation.

They are to be doubly blamed for that. First, it was politically unwise. Then

again it was in glaring contradiction to their hitherto professed concept of

non-resistance. The Russian peasants pointed out this contradiction and

called them hypocrites. A bitter truth

was held up to the [Mennonite] colonists: 'When our Russia, our women and

children, were threatened with attack in 1914, then you refused to take up

arms for defensive purposes. But now that it's a question of your own

property you are arming yourselves.' Certainly it was a crying shame that the

[Mennonite] colonists' actions were inspired neither by a desire to protect

the state nor by a true Christian spirit. We

Mennonites are aliens in this land. If we didn't realize that fact before the

war we have had it forced upon us during and after the War. Our Russian

neighbors look on us as the damned Nyemtsy

[Germans] who have risen to great prosperity in their land. They completely

ignore the fact that our forefathers were invited here [one hundred and

thirty] years ago in order to cultivate the vast steppes which lay idle at

the time. They refuse to admit that our farmers were able to achieve more

than Russian farmers by dint of industry and perseverence,

as well as through bet¬ter organization and

management, rather than through political means. ... This

is no longer our homeland. We want to leave! The magic word 'emigration'

travels like a buran [winter wind] from place to

place. Whenever two or three colonists get together the conversation is sure

to be about emigrating. It is the one idea that keeps us going, our one hope. SOURCE: Dietrich Neufeld, A Russian Dance

of Death: Revolution and Civil War in the Ukraine, translated by Al Riemer (Winnipeg 1977), pp. 11, 18-19, 26-27, 63-64, 73,

79. |

|

|