|

|

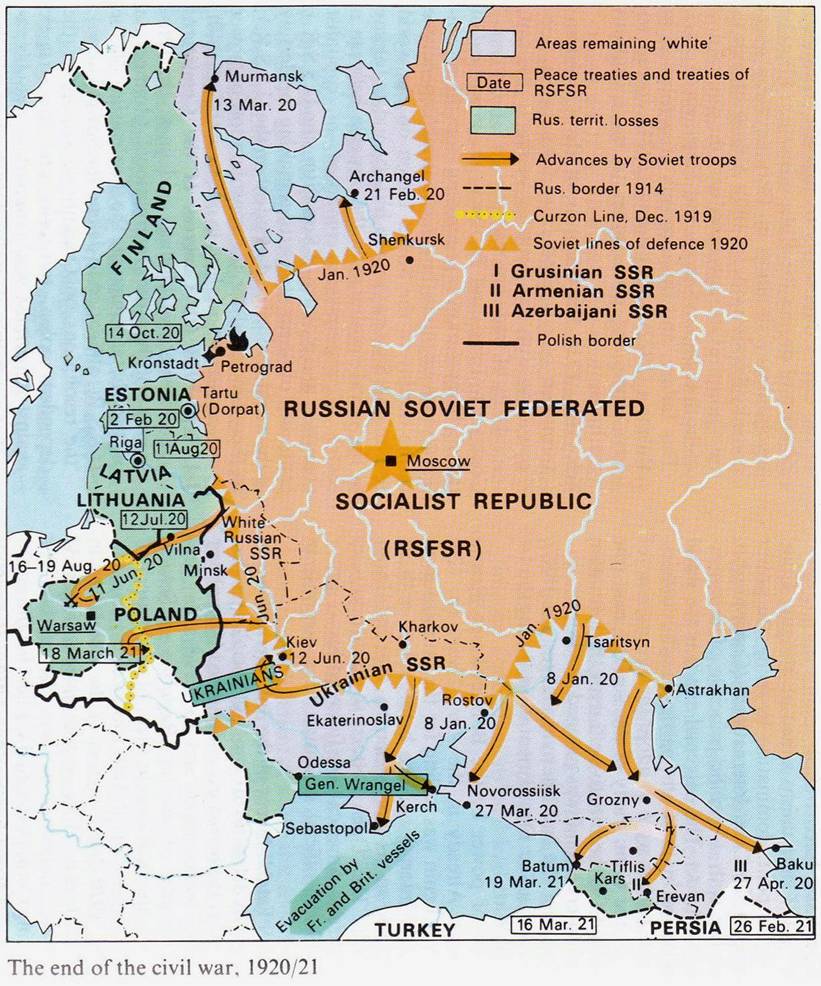

WHY DID THE REDS WIN? Tatyana Shvetsova Map: The Penguin Atlas of World History / 1995 |

||

|

|

By the

end of 1920 the Civil war in So, why

did Soviet power win and how can we explain the defeat of its numerous

enemies? Doctor

of History, Professor of Murmansk Pedagogical Institute Alexei Voronin

insists that ‘the Bolsheviks won not so much due to their own strength, but

rather due to the weakness of their enemies’. “Almost

every war changes the social setup of the warring sides, bringing it closer

to the military-socialist type,” Alexei Voronin elaborates. “In such a society

the degree of the authorities’ interference in the life of its citizens is

unlimited. This society is characterized by total centralization, ruling out

the very existence of private property. The entire organization of such a

society, right down to the psychological portrait of its members is oriented

to war and is permeated with militarism. In other words, war creates the most

conducive conditions for ‘socialization of society’. Yet, the question is:

who and how makes use of these conditions. Do they accept these conditions

out of forced necessity, or do they regard them as an imperative precondition

for exercising their policy? Obviously,

the Bolsheviks, if we can say so, coincide maximally with the conditions of

the war period. They felt perfectly at ease in the conditions of war –

something that quite possibly serves as one of the reasons for their ultimate

success. As for

their enemies, quite the opposite, they tended to find oppressive those

‘military-socialist’ measures they were also forced to apply. In other words,

they conducted the same policy less consistently, with less austerity, and as

a result – to less effect.

The

success of the Bolsheviks was achieved in conditions of approximate equality

of the opposing sides in many respects, first and foremost – the military.

So, it is important to understand where exactly lies the reason for their

victory. One could, in all likelihood, define it in the following way: the

Bolsheviks scored a victory not so much due to their own strength, as due to

the weakness of their enemies. The

Civil war of 1917 – 1921 was a de facto implementation of a radical

alternative. This alternative was victorious because the solutions to

outstanding contradictions in the life of Russian society, offered by the

conservatives and liberals, were deficient. It was the failures of the

conservatives and liberals that predetermined the success of the Bolsheviks.”

Doctor

of History Professor Olshtynsky believes that, “the main factor that

determined the victory of the Bolsheviks was the union of workers and

peasants that supported the Soviet power. The second reason lies in the

ideals of national-liberation, pursued by the Civil war. The fusion of

counterrevolution and foreign intervention turned the actions of Soviet authorities

into a struggle for The third

reason can be found in the extremely well-organized and welded leading

political force of Soviet power – the party of Bolsheviks. It was through its

efforts the many-million–strong, battle-worthy Red Army was founded. The

Soviet state managed to transform the country into one cohesive military

camp, where all of society’s forces were mobilized for armed struggle. Finally

– a factor that contributed to victory was the support of the International

working class. The workers’ movement “Hands off Soviet Russia” and the

upsurge of the revolutionary movement in the armies of the foreign

intervention forced the Entente to withdraw its armed forces from Vladimir

Lenin announced after the victory in the Civil war: “Nobody

will ever conquer a people whose workers and peasants in their majority

have experienced, seen and felt that they are …fighting for a cause, victory

in which will enable their children to avail themselves of all the

boons of culture, the fruit of man’s labour.” He also

said: “Firstly, we won over from the Entente its workers and peasants;

secondly, we have enlisted the neutrality of those small peoples, who are its

slaves; thirdly, we have started attracting to our side in the countries of

the Entente their educated petite bourgeoisie…This is our third large victory.

It became a victory not only on a Russian, but on an international-historical

scale.” A

historian from the town of Saratov, an expert in the sphere of conflictology,

Assistant Professor at the Civil Service Academy of the Volga district, Anton

Posadsky, is convinced: “…most decisive was the fact that in the case of the

Bolsheviks the scale of their actions was quite different from that of the

‘whites’. For the ‘reds’ the whole of The

‘whites’ didn’t dare to uncompromisingly destroy what was theirs, so dear to

them. The ‘reds’ were stronger in their instrumental approach to what was

formally their own country. They succeeded in finding the most painful spots

in the system and making use of them, never tormented by any moral doubts or

historical considerations.” Historian

Sergey Sbortsev from the capital of Byelorussia Minsk says: “The

main reason for the victory of the Bolsheviks lies in the fact the ‘white’

movement couldn’t find broad support inside the country. It placed its bet

with the privileged classes and failed to enlist the support of the broad

sections of the working population by gaining their interest with their

economic program. The Bolsheviks, quite the opposite, could fall back on the

greatest support of the population, particularly the poorest sections of it.

The tactical strength of the Bolsheviks lay in the fact they spoke on behalf

of the people - something that came to play a decisive role and brought them

in their victory in the Civil war.” Politologist

of left-wing views Sergey Kara-Murza insists that the Bolsheviks won because:

“…the turned out to be the only political force, that could save One of

the factors that was conducive to bringing about the victory of the

Bolsheviks in the Civil war was the significant number of professional

military exerts from the former Czarist army that went over to their side.

Making a note of this, well-known Russian publicist Vadim Kozhinov cited

information published by the magazine ‘Voprosy Istorii’ (or ‘History

Issues’). It was said there that “the overall number of cadre officers, who

participated in the Civil war within the ranks of the Red Army was double the

number that took part in the war action of the side of the ‘whites’.

Commenting this data, the publicist reflects: “…one should first and foremost

realize that whilst serving within the ranks of the Red Army (at times

occupying high and most responsible posts), these officers and generals never

became ‘red’ themselves. There was but the occasional Bolshevik party member

among them. The Revolutionary military Council of the Republic noted in 1918

that “the higher the rank, the less communists one could find among them”. All this

testifies to the fact that the Russian officers and generals who ‘opted for

the Red Army’, were thus choosing the lesser of the two evils. These were

people who, quite obviously, were well-familiar with their colleagues in

military service from the White Guards. They could see that standing at its

head were ‘unrepentant children of the February revolution’. While the

February revolution was a destructive force for the Russian state and, first

and foremost, for the army.” As for

the reasons why the ‘whites’ suffered a defeat, there are quite a lot of

them. There is the obvious egotism of the higher social circles, the

treachery of the ‘allies’ in the Entente, who favored the Bolsheviks. British

Premiere Lloyd George openly admitted in his memoirs that the allies “had

done everything possible to support the Bolsheviks”. They acknowledged that

the Bolsheviks were de facto the ruling force on the territory of the former

Russian Empire. They certainly had no intention of lifting a finger to help

topple the Bolsheviks. All the “allies” needed while World War One was still

raging was for the Bolsheviks not to destroy the “White Guard” officers who

were prepared to fight alongside the Entente against Well-known

Russian publicist and historian Mikhail Nazarov wrote: “The white movement

didn’t score a victory primarily because it relied on force of weapons, and

underestimated the spiritual reasons for the Russian catastrophe…” And the

main reason for this catastrophe, writes Mikhail Nazarov, was a rejection of

God and the Orthodox Faith. To substantiate this opinion he quotes from the

memoirs of a participant of the White movement baron Meller-Zakomelsky: “…We

realized too late that socialism-communism was a religious phenomenon, and

victory over it was possible only through a religious upsurge of the

Christian Faith. Humbly deploring our infirmity, in utter compassion and

repentance, in love for our errant brethren, we shall seek the true road to

recovery. It is not a sword forged in hatred and vengeance, but the Cross -

Christ’s pure token – that will lend us the strength needed for victory.” Only in

emigration, writes Mikhail Nazarov, did the White idea acquire completeness –

after its proponents realized their own mistakes and assessed the world

alignment of forces. On a political level this became a denunciation of the

united global front of destroyers of the Orthodox Russia. On this front the

communist-Bolsheviks and the liberals, who had masterminded the February

revolution, were enemies only outwardly. In essence, though, they were

allies, since both forces sought to destroy the Orthodox Russian state. The

difference between them lay only in WHAT STATE EXACTLY EACH OF THEM SOUGHT TO

BUILD IN PLACE OF THE DESTROYED ORTHODOX RUSSIAN EMPIRE. The

outcome of the Civil war was terrifying, indeed. In the words of historian

Oleg Platonov: “…the overall number of casualties in the war comprised no

less than 18,7 million people… Out of

this number we should single out those who died of starvation, illness,

epidemics, or were forced to flee from In the

years of the Civil war some 20 to 25 million people suffered in epidemics.

The typhus epidemic claimed the greatest number of victims. As for

those who died of starvation, the number is estimated at 10,1 million. It was

the large cities that suffered the most. Thus, in the years of the Civil war

the population of A

direct outcome of the Civil war was the vast stream of emigration. Some 2

million people left It was

the Russian population that suffered the most in the Civil war. Its quota in

the overall population of the Soviet Russia dropped by three percent. The

country had lost the crème de la crème of the Russian nation, its golden gene

pool. Representatives of the national elite were either totally wiped out or

forced to flee abroad. The entire Russian national and intellectual

infrastructure was destroyed. Thus, around 40 percent of the Russian

professorate and doctors had died.” However,

In the

words of Byelorussian historian Sergey Sbortsev, “the losses that the people

of The

Civil war with its red and white terror became a tragedy for all peoples

living in Doctor

of History, Professor of Murmansk Pedagogical Institute Alexei Voronin wrote:

“The political success of the Bolsheviks turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory.

Political effectiveness resulted in economic ineffectiveness. This, in turn,

questioned the political victory itself. Objective requirements for the

advance of the economy came into obvious conflict with the aims pursued by

the communists. Quite naturally, this cast doubt on the possibility of their

retaining power. This threat manifested itself in the anti-Soviet and

antibolshevist protests that were widespread across all of Copyright © 2006 The Voice of Originally

published at http://www.vor.ru/English/homeland/home_034.html 01/30/2006 |

|

|