|

|

A. Historical Background. There

had been many Polish-Russian wars over the borderlands, that is Belarus (formerly Belorussia),

Ukraine, and the lands

that would later become Lithuania,

Latvia and Estonia.

At its greatest extent, in the early 1600s, Poland

had included most of these lands, but gradually retreated as Russia

expanded. Russia acquired some Belorussian and Ukrainian lands in the 17th

century, plus what is today Latvia and Estonia in the early 18th

century, while it acquired the rest of the borderlands as well as most of

ethnic Poland in the Partitions of 1772-95.

From that time on, Russian governments looked on the borderlands, and

especially Russian Poland

(which was ethnically Polish), as vital for Russian security. They pointed to

Napoleonís invasion of 1812 and to WWI, when the German and Austro-Hungarian

armies drove the Russians out of Poland by the fall of 1915.

General Brusilov's offensive pushed the Austrians out of East Galicia in

summer 1916, but the Russians were driven out of this region in summer 1917

and the Germans and Austrians occupied most of the borderlands until the end

of WW I.

Imperial Russian governments and

propaganda claimed the borderlands were ethnically Russian, because they

viewed the Belorussians and Ukrainians as "little brothers."

However, these peoples developed their own national identities in the course

of the 19th century. Furthermore, there were large Polish minorities in what

is today western Belorussia,

western Ukraine and

central Ukraine.

According to the Polish Census of 1931, Poles

made up 5,600,000 of the total population of eastern Poland which stood at

13,021,000.* In Lithuania, Poles had majorities in the Vilnius [P. Wilno,

Rus. Vilna] and Suwalki areas, as well as significant numbers in and around

Kaunas [P.Kowno].

*[Ukrainians numbered 4,303,000; Belorussians

1,693,000; Jews 1,079,100; Russians 125,800; Germans 86,200; Czechs 31,000,

see: Marek Tuszynski, "Soviet War Crimes Against Poland During the

Second World War and Its Aftermath. A Review of the Record and Outstanding

Questions," Polish Review, no.3, 1999. The Ukrainians and

Belorussians were undercounted in 1931. Tuszynski notes that by October 1939,

there were an additional 1,579,000 Polish citizens in these territories, not

counting 379,000 Polish refugees from the Warsaw district, see note 9 ibid].

B. 1917-1919.

(i) The Soviet advance westward. 1918-19.The

Soviet government claimed to support the "self-determination" of

all the non-Russian peoples of the former Russian Empire. However, they meant

self-determination by workers and peasants led by native communists sent in

from Moscow.

The Soviet government could not help the communists in Finland, who were too weak to succeed by

themselves, and Moscow failed in a bid to take

over the Baltic States.

However, in 1918 the Soviets managed to take

over most of Ukraine,

driving out the Ukrainian government from Kiev,

and they also set up a "Lithuanian-Belorussian

Republic "(Litbel) in

early 1919, with its government in Vilnius

[Wilno]. It was run by native communists sent there by Moscow and supported by Red Army units.

This government made itself very unpopular due to confiscation of food and

goods for the army, as well as terror.

(ii) A Polish Communist Workersí Party

was established in Warsaw

in late December 1918. It was made up of the left wing of the Polish

Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Party of the Kingdom

of Poland and Lithuania. This new party called

for the overthrow of "bourgeois Poland," and was therefore

declared illegal.

C. The Polish-Soviet War.

As German troops pulled out of Belorussia

in late 1918 and early 1919, Red Army troops began to seep in. Polish troops

advanced east and clashed with them at Bereza Kartuska in February 1919.

In April, the Polish army drove the Litbel government out of Wilno/Vilnius,

which then had a predominantly Polish and Jewish population (about 50-50),

some Belorussians and only about 2% Lithuanians.

The French and British governments, who

supported the Whites in the Russian Civil War, tried to persuade Pilsudski

to go on fighting the Red Army, but to keep recovered eastern territories

"In trust" for Russia. He refused and proposed that a plebiscite be

held in the borderlands under League of Nations

auspices, but the western powers ignored this offer. Therefore, Pilsudski

adopted a passive stance toward the Russian Civil War, not helping either the

Whites or Reds, but objectively helping the Reds because he did not attack

them.

In December 1919, the Red Army was

clearly winning the Civil War and the Soviet government sent peace proposals

to the Polish government. Pilsudski rejected negotiations, suspecting

the Soviets only wanted a breather before attacking Poland. At this time, the French

and British were pulling their troops out of Russia and wanted to avert a

Polish-Soviet war.

On 8 December 1919, the Allied

Supreme Council in Paris

proposed a demarcation line between the Polish and Russian

"administrations." This line, which was specifically stated not

to be the frontier, was roughly equivalent to ethnic Poland, but had two

possible variations in East Galicia: one which left Lwow [Ukr Líviv,

Rus. Lvov] then predominantly Polish, and the neighboring oil fields, on the Russian

side (Line A) while the other left them on the Polish side (line B).

Pilsudski ignored this proposal. His goal was a federation between Poland, Lithuania

and Belorussia, allied

with an independent Ukraine.

Leninís aim was to infiltrate the

borderlands, set up communist governments there as well as in Poland, and reach Germany where he expected a

socialist revolution to break out. He also expected revolutions elsewhere,

including Italy, but the

German revolution was most important to him for he believed that Soviet

Russia could not survive without the support of a socialist Germany and the help of its industrial

know-how to modernize Russia.

In March 1920, Pilsudski learned

from military intelligence that the Red Army was concentrating in Ukraine.

He suspected an attack on Poland

and, indeed, published Russian documents on the Civil War show that such an

attack was planned, though its first thrust was to be into Lithuania. However, inclement

weather postponed the Soviet offensive.

Pilsudski decided on a preventive attack

and concluded an alliance with the Ukrainian leader Semyon Petliura

(1879-1926). He had fought the Bolsheviks in defending Ukrainian

independence, was defeated and fled to Poland with his remaining troops.

The Polish-Ukrainian alliance treaty, signed April 22 1920, had the

goal of establishing an independent Ukraine

in alliance with Poland.

In return, Petliura gave up Ukrainian claims to East Galicia

(today western Ukraine),

and was denounced for this by the Ukrainian leaders there. The treaty

included guarantees for the rights of the Ukrainian minority in Poland and the Polish minority in Ukraine.

At the end of April, the Polish army and

Petliuraís Ukrainian divisions, marched east into Ukraine. They entered Kiev on May 7, and an independent

Ukrainian state was proclaimed there. However, the expected Ukrainian

uprising against the Russians did not take place. Ukraine was ravaged by war; also,

most of the people were illiterate and had not developed their own national

consciousness. Finally, they distrusted the Poles, who had formed a large

part of the landowning class in Ukraine up to 1918.

In June 1920, a Red Army offensive drove

out the Poles who retreated westward, and was approaching Warsaw in late June. On July 2, the Soviet

commander, Mikhail N. Tukhachevsky (1893-1937), issued an

"Order of the Day" to his troops calling them to press "onward

to Berlin over the corpse of Poland!"

A group of Polish communists headed by Felix Dzerzhynsky (P.

Feliks Dzierzynski), now head of the Cheka (Soviet Secret Police),

set up a Polish Revolutionary Committee in Bialystok, It was

clearly the embryo of a communist government for Poland.

In this situation, the Polish government sent a

delegation to Spa,

Belgium -

where the French and British prime ministers were meeting to discuss German

reparation - and ask them for help. British Prime Minister David

Lloyd George was furious with the Poles for marching into Ukraine because he was negotiating a trade

agreement with the Bolsheviks in London; also,

he feared a German revolution if the Red Army reached Germany. Therefore, the British

government proposed a demarcation line based on the Supreme Council Line of

December 8, 1919, but this was now called the "Curzon Line"

after British Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon (who did not draw it up).

The Poles agreed to negotiate with the Soviets on the basis of this line -

which the British extended without telling them, into East

Galicia, leaving it on the Soviet side - but the Bolshevik

government. sure of victory, refused. Meanwhile, an Anglo-French

diplomatic mission and a military mission was sent to Poland as a sign of allied

support for her independence. The French General Maxime Weygand

(1867-1965) was to take over command of the Polish army. He arrived with some

French officers, including captain Charles De Gaulle (1890-1970,

leader of the Free French in World War II, head of governments 1945-46,

President 1958-69).

The Poles were in a very difficult position. Germany proclaimed neutrality and refused

passage to French arms and munitions for Poland. In Czechoslovakia, railway workers refused to let

trains with military supplies go through to Poland.

British dock workers sympathized with

theBolsheviks, so they threatened to strike if ordered to load ships for the

Poles.

The only way French supplies could reach Poland was through Danzig.[P. Gdansk],

but Lloyd George, who was negotiating a trade treaty with Bolshevik

delegates in London, ordered the British League High Commissioner Sir Reginald Tower,

to refuse permission for unloading French ships, and the German Danzig

dockers threatened to strike if they were ordered to unload them.

At this time, the Poles unloaded some supplies in the fishing port of Gdynia,

about 20 miles west of Danzig in the "Polish

Corridor." (This experience led to the developmnt of Gdynia

into a Polish port city; work began there in 1924).

As it turned out, General Weygand was not

welcome to take over command of the Polish army. He then advised the

Poles to abandon Warsaw and set up a defense

line on part of the Vistula river.

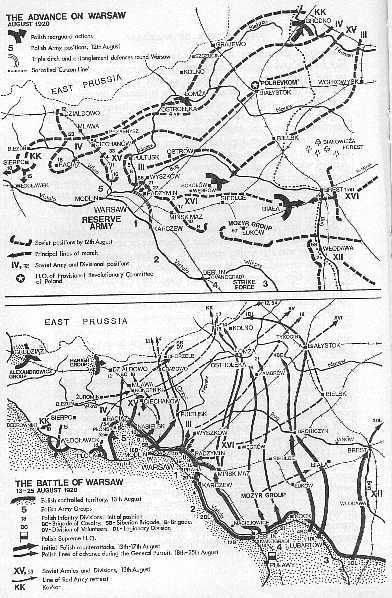

Pilsudski refused. He and his chief of

staff, General Jordan T. Rozwadowski (1866-1928) drew up a daring plan

of attack. Some Polish troops were withdrawn from the Warsaw perimeter and concentrated in a

strike group south of the city.

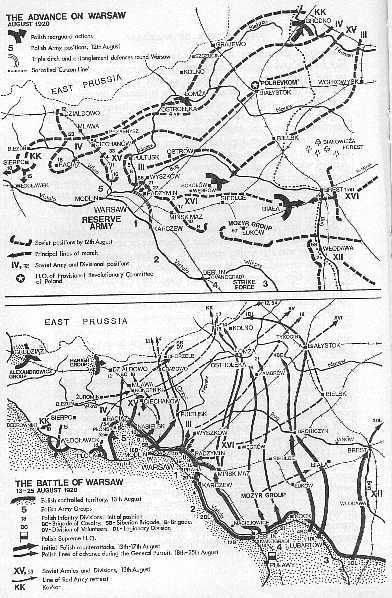

On August 13, Pilsudski launched the

attack toward the north-north west. He drove between the Red Army groups

North and Center, and came up in the rear of Tukhachevskyís army group which

was outflanking Warsaw and had reached East Prussia.

The Red Army was defeated. This is known as

the "Battle of the Vistula," or "The

Battle of Warsaw." In the West, the victory

was attributed to General Weygand. He denied this, but got used to the idea

with time and came to see himself as the savior Poland. (Most textbooks on the

history of Modern Western Europe do not mention the Polish victory). In

September, Pilsudski defeated Tukhachevsky again at the Battle

of the Nemen river in Lithuania.

[fom Norman Davies, White Eagle, Red Star, London, 1972]

|

POLISH

GENERALS

Joseph Pilsudski

|

|

|

|

|

Lucjan Zeligowski

|

Kaziemerz Sosnkowski

|

|

SOVIET

COMMANDERS

|

|

|

|

|

Mikjail Tukhachevski

|

Alexander Yegorov

|

|

|

|

|

Semuyon Budyonnyi

|

Ghai-Khan

|

[Maps, pictures and captions,

Norman Davies, White Eagle Red Star,London, 1972]

We should note that the Polish army was made up

of both conscripts and volunteers. The peasants made up the infantry and the

rank-and-file of the cavalry. The Red Army also used infantry and cavalry,

notably the Budenny "Konarmia" or horse army commanded by

Semyon M. Budenny (1883-1973, pron. Boodyonny), to which Iosif [Joseph]

V. Stalin (1879-1953), the future Soviet dictator, was

attached as Commisar, or chief political officer.

†

The Polish army also used armored trains, which with their heavy guns were

like warships on land. They also transported heavy artillery, horses, and

planes.

†

There was a small Polish air force,and some of the pilots were American

volunteers from the Lafayette Squadron, France. They flew in the the Kosciuszko

Squadron in Poland.

The pilots found after a while that they could not shoot up Russian troops

with impunity because the Red Army had machine guns mounted on

"tachankas," that is, fast moving, small, two wheel horse carts.

The Poles also used them and each side claimed the invention.

But the war was mainly a fast moving cavalry

war on both sides. It helped the cavalry to survive in the interwar period as

an important part of both the Polish and the Red Army.

As mentioned earlier, in early July the Soviet

government refused the offer of the Curzon Line. In the official answer, given

by the Commissar of Foreign Affairs, Georgii V. Chicherin (1872-1936),

the Bolshevik government said it desired direct negotiations with the Poles

to whom it would offer far more territory than the Curzon Line. Encouraged by

the British, the Poles agreed to negotiate.

However, the Soviet demands put to the Polish delegation in August in Minsk were draconian.

They involved not only loss of territory (basically the Curzon Line

with East Galicia, thus leaving Lwow/Líviv and the oil fields to the Soviets,

though with modifications in Polandís favor in the Bialystok and Chelm

[Kholm] regions), but also disarmamen, the establishment of a

"workersí militia," and the Soviet right of free transit of

passengers and goods through Poland along the Volkovysk-Graievo railway,

which was to be in Soviet possession. The acceptance of these terms

would have made Poland

a Soviet satellite. The Poles refused, though Lloyd George

had urged them to accept. (The French did not).

After the defeat of the Red Army, Lenin gave

a confidential explanation of why his government had refused the Curzon Line

offer and continued the advance into Poland. It is worth citing because

of the insight it gives into Leninís thinking in July 1920 and of Polandís

key place in it. At a closed meeting of the 9th Conference of

the Russian Communist Party on September 22, 1920, Lenin said:

We

confronted the question: whether to accept [Curzonís] offer, which gave us

convenient borders, and by so doing, assume a position, generally speaking,

which was defensive, or to take advantage of the enthusiasm in our army and

the advantage which we enjoyed to sovietize Poland. ..

...we arrived at the

conviction that the Ententeís military attack against us was over, that the

defensive war against imperialism was over, we won it... The assessment went

thus: the defensive war was over (Please record less: this is not for

publication).

...We faced a new task...We

could and should take advantage of the military situation to begin an offensive

war...This we formulated not in the official resolution recorded in the

protocols of the Central Committee...but among ourselves we said that we

should poke about with bayonets to see whether the socialist revolution of

the proletariat had not ripened in Poland...

[We learned] that somewhere

near Warsaw lies not [only] the center of the Polish bourgeois government and

the republic of capital, but the center of the whole contemporary system of

international imperialism, and that circumstances enabled us to shake that

system, and to conduct politics not in Poland but in Germany and England. In

this manner, in Germany

and England

we created a completely new zone of proletarian revolution against global

imperialism.....

. ..By destroying the Polish

army we are destroying the Versailles Treaty on which nowadays the entire

system of international relations is based.....Had Poland become

Soviet....the Versailles Treaty ...and with it the whole international system

arising from the victories over Germany, would have been destroyed. *

*[English translation quoted

from Richard Pipes, RUSSIA UNDER THE BOLSHEVIK REGIME, New York, 1993,

pp.181-182, with some stylistic modification in par 3, line 3, by

A.M.Cienciala. This document was first published in a Russian historical

periodical, Istoricheskii Arkhiv, vol. I, no. 1., Moscow,1992].

After Tukhachevskyís second and final defeat on

the Nemen river in September 1920, the Soviet government decided it needed

peace to stay in power. An armistice with Poland

was signed in Riga, Latvia, on October 12, 1920 and

peace negotiations began in that city.

The negotiations for a peace treaty dragged on

for months due to Soviet reluctance to sign. However, in Feb. 23- March

171921, the Soviet govt. faced a sailorsí revolt in Kronstadt which

was brutally crushed by troops led by Tukhachevsky. But peasants

were also rising up against Soviet authorities, who were confiscating all

their food to feed the Red Army and the workers in the cities. In view of

this situation, Lenin ordered the Soviet plenipotentiaries to secure a peace

treaty. This led to the signing of the Treaty of Riga on March 18, 1921. It established

the Polish-Soviet frontier until the Soviet attack on Poland in mid-September 1939. It

was a compromise peace for both sides, because Pilsudski gave up his

plans for a federation with Lithuania and Belorussia and alliance with an

independent Ukraine, while Lenin gave up his plans for exporting the

revolution West, at least for the time being The Soviet government never

accepted the new frontier and was determined to change it in its own favor as

soon as opportunity arose. * The Ukrainians blamed the Poles for giving up

the fight and thus the chance of Ukrainian statehood, but the Polish people

were exhausted and public opinion opposed the prolongation of the war.

Pilsudski apologized to the Ukrainian officers who had helped the Poles fight

the Red Army, but now lost their struggle for an independent Ukraine.

[For thePolish-Ukrainian war over East Galicia,

see B below].

†

[Brief Bibliography on the Polish-Soviet War

*[For the military side of the Polish-Soviet

War, see Norman Davies, White Eagle, Red Star. The Polish-Soviet War,

1919-1920, London, New York, 1972 and reprints. For the

accounts of the two commanders-in-chief, see Jozef Pilsudski, [THE] YEAR 1920

AND ITS CLIMAX, BATTLE OF WARSAW, London,

1972. It includes Tukhachevskyís account to which Pilsudski was replying. For

the diplomatic side, see Piotr S.Wandycz, Soviet-Polish Relations,

1917-1921, Cambridge,

Mass., 1969. For these and

other sources see John A. Drobnicki, "The Russo-Polish War, 1919-1920: A

Bibliography of Works in English," The Polish Review, vol. XLII

[42], no. 1, New York,

1997, pp. 95-104.

For a western view sympathetic to Soviet

Russia, see Louis Fisher, THE SOVIETS IN WORLD AFFAIRS. A History of the

Relations between the Soviet Union and the Rest of the World, 1917-1929,

2d Printing, Princeton N.J.,

1951 vol. I., ch. VI. White Poland vs. Red Russia. The work first appeared in

1930. In the Introduction to the 2nd printing, Fisher thanked

Soviet Commissar of Foreign Affairs, Chicherin, for helping him with

the research, for reading the whole work and giving Fisher his comments.

Fisher also thanked Chicherinís assistant, then successor, Maxim M.

Litvinov (1876-1951) and other Soviet dignitaries. Therefore, Fisherís

work can be seen as reflecting the views of Soviet policy makers in the late

1920s].

Significance of the Polish victory.

(i) It saved not only Poland but also the Baltic States and perhaps

the rest of Central Europe as well from

Soviet conquest, thus allowing the development of independent states in this

area.

(ii) It forced the Soviet government to focus

on rebuilding the Russian economy, by introducing the "New Economic

Policy" (NEP), a mixture of socialism and capitalism (1921-28).

However, neither the factors leading to the

Polish-Soviet war, nor the significance of its outcome were understood by

most observers in the West. On the contrary, many people accused Poland

of having started an "imperialist war" against Soviet Russia and of

annexing "Russian" lands, though these were inhabited by

Belorussians and Ukrainians. At the time,these peoples were not strong enough

to become independent and as it turned out, they were to suffer much less

under Polish rule than their brothers in the USSR who came under the iron fist

of Joseph V. Stalin.

††††††††††† Originally published at http://raven.cc.ku.edu/~eceurope/hist557/lect11.htm

|

|

Anna M. Cienciala

Professor

Emerita / The University of Kansas

hanka@ku.edu

B.A. Liverpool, 1952, M.A. McGill, 1955;

Ph.D. Indiana, 1962

20th century Polish, European, Soviet,

and American diplomacy 1919-1945.

Born in the Free City of Danzig (Gdańsk, in Poland after WWII); she attended middle

and high school in England; university studies in England, Canada, and U.S.

(B.A. Liverpool, 1952, M.A. McGill, 1955; Ph.D. Indiana, 1962). She taught

at the University of Ottawa and the University of Toronto before coming to

the University of Kansas in 1965. More info

|

|

|