|

|

Interwar

|

Preface:††††††††† DOMESTIC PROBLEMS AND FOREIGN POLICIES OF

INTERWAR EAST EUROPEAN STATES

These problems and

policies should be viewed within

(a) the context of the beliefs/perceptions of historians

today, and

†(b) the realities of E.Europe at this time.

(a) Current western

beliefs/perceptions.

1 Under the impact of

the internecine ethnic/religious wars of the 1990s in

the lands of former

2. In this context, some contemporary western historians condemn

President Woodrow Wilson for his insistence on the principle of

self-determination in 1919. At the same time, these historians condemn the peace makers in

3. Finally,

some western historians view federalization as the best solution for East

Central European Danubian states in 1919-20, and thus

condemn its rejection when offered by Emperor Charles for Austria

and Michael Karolyi for Hungary in Nov-Dec. 1918,

also later rejections of similar projects.

(b) These views

may seem attractive but they are out of touch with East European realities of

the time and therefore unrealistic. To start with the last view :

1. The majority of

non- German/Austrian and non-Magyar peoples

rejected the federal solution in either

2.

Ethnic-national states were not created by Woodrow Wilson or the peace settlement

of 1919; nor were they an East European

aberration. This process was, in fact, the

continuation of the national unification movements that had already taken

place in Western Europe, especially in

3. Contrary to

conventional wisdom, most of the new borders of East European countries

were not fixed by western statesmen drawing maps in

4. Of course, it was impossible to establish borders satisfactory

to every ethnic nationality because of the inter-mixing of peoples in the past,

and esp. because of long foreign rule. The natural outcome of this state of

affairs in 1919 was that the nations which had opposed the Central Powers in

the war: the Poles, Czechs, Serbs, Romanians, who also had sufficient

armed forces at their disposal, were able to include territories with

significant minorities within their borders. The Poles were able to do this in the

east because of their victory over the Red Army.

Keeping the above

realities in mind, let us look at the East European States of the interwar

period.

General Characteristics and

Problems.

The interwar period

was short, lasting just over 20 years if we start in Jan .1919, or a few months

longer if the starting point is November 1918. However, this short period had

enormous significance for these countries because: (a) they could develop their

own politics, administration, economies,

education, and culture; (b) their very existence legitimized them in the eyes

of the world. After this period, they could not be obliterated either by Nazi

Germany or the Stalinist USSR.

Joseph Rothschild (d. Dec.1999) , an American political scientist and author of books on

Eastern Europe, wrote that even communist historians joined

"bourgeois" emigre scholars "in

valuing highly the sheer fact of interwar state-independence, and judging it to

be a historic advance over the areaís pre-World War I political status."

He also gave a balanced judgment on these countries' performance in the

interwar period:

Thus, despite major and avoidable failings (too little area-wide

solidarity, too much over-politicization of human relations, too little

strategic government intervention in the economy, too much petty government

interference with the society), thanks to the political performance of the

interwar era it is impossible today to conceive of East Central Europe without

its at least formally independent states. In retrospect, one must assign

greater responsibility for the catastrophes of 1939-41 to the malevolence,

indifference, or incompetence of the Great Powers than to the admittedly costly

mistakes of these states. *

*[Joseph Rotschild, East Central Europe

Between the Wars, Seattle, WA. 1974, and reprints, pp. 24-25; bold italics,

AMC].

We must bear in mind

that the interwar East European states faced enormous problems, most of which

could not be solved in twenty years, especially in view of the paucity of

foreign capital investment before the Great Depression struck in 1930, and

virtually none after that. Furthermore, they faced the growing threat of Nazi

Germany from 1935 onward.

Many problems of East European states were inherited

from the former empires, a fact acknowledged by the British historian Hugh

Seton-Watson, whose negative evaluation of interwar

*[Hugh Seton-Watson, Eastern

Europe between the Wars, 1918-1941, Preface to 3rd edition

revised, Harper Torchbooks, New York, 1967.].

Unfortunately, few

people bother to read prefaces, and this is a case in point.

In fact, the

problems were much more numerous than those listed by Rothschild. There

were 10 key problems:

†

(1).economic backwardness; (2). agrarian,

unmechanized economies; (3). overpopulation

on the land; (4).peasant poverty; (5).bad roads and insufficient railway track;

(6).lack of a middle class; (7). lack of adequate

numbers of trained bureaucrats; (8). widesrpread

illiteracy; (9). lack of experience, or restricted

experience with parliamentary politics and participation in any kind of

government; (10). lack of investment capital.

The exception

to all these problems was Czechoslovakia, where the western Czech

lands of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia had a highly developed industry, a

prosperous agriculture, an excellent road and rail network, a highly literate

population, a numerous and well trained bureaucracy, experience in

parliamentary government and considerable capital resources. However, of the

other two constituent parts of the country,

Two other problems

which most E.European countries had in common were either

multi-ethnic/national populations or/and significant ethnic/national

minorities whose loyalties belonged to, or leaned toward neighboring

national states. In

This state of

affairs, though inevitable at the time, deepened the general feeling of insecurity.

Indeed, the discrimination against the constituent or so-called ruling

nationalities in Czechoslovakia (Slovaks and Rusyns),

Yugoslavia (non-Serbs), and the discrimination or oppression of national

minorities in most East European countries, stemmed primarily from fear that

constituent nationalities as well as minorities, could, and probably would

given the chance, undermine the sovereignty of the countries in which they

were resentful citizens, and lead to the reduction of their territory or even

their destruction. We must bear this insecurity in mind when we look at

minority policies in the interwar East European states.

The above fears were

intensified by the general, international insecurity in the 1930s, which made

territorial disputes more threatening than they would have been otherwise.

Thus, the states allied with France: Poland and Czechoslovakia,

feared

The largest

state in the region,Poland,

had two potential enemies:

Political systems.

The general trend of

East Central European political development was

from parliamentary democracy, including strong Socialist parties at the outset,

to various kinds of authoritarian government. But it should be

noted that while fascist parties or groups existed in each country, no

interwar East European state had a fascist party in power as was the case in

Germany, Italy, Spain and Portugal, while a totalitarian communist. system existed in the

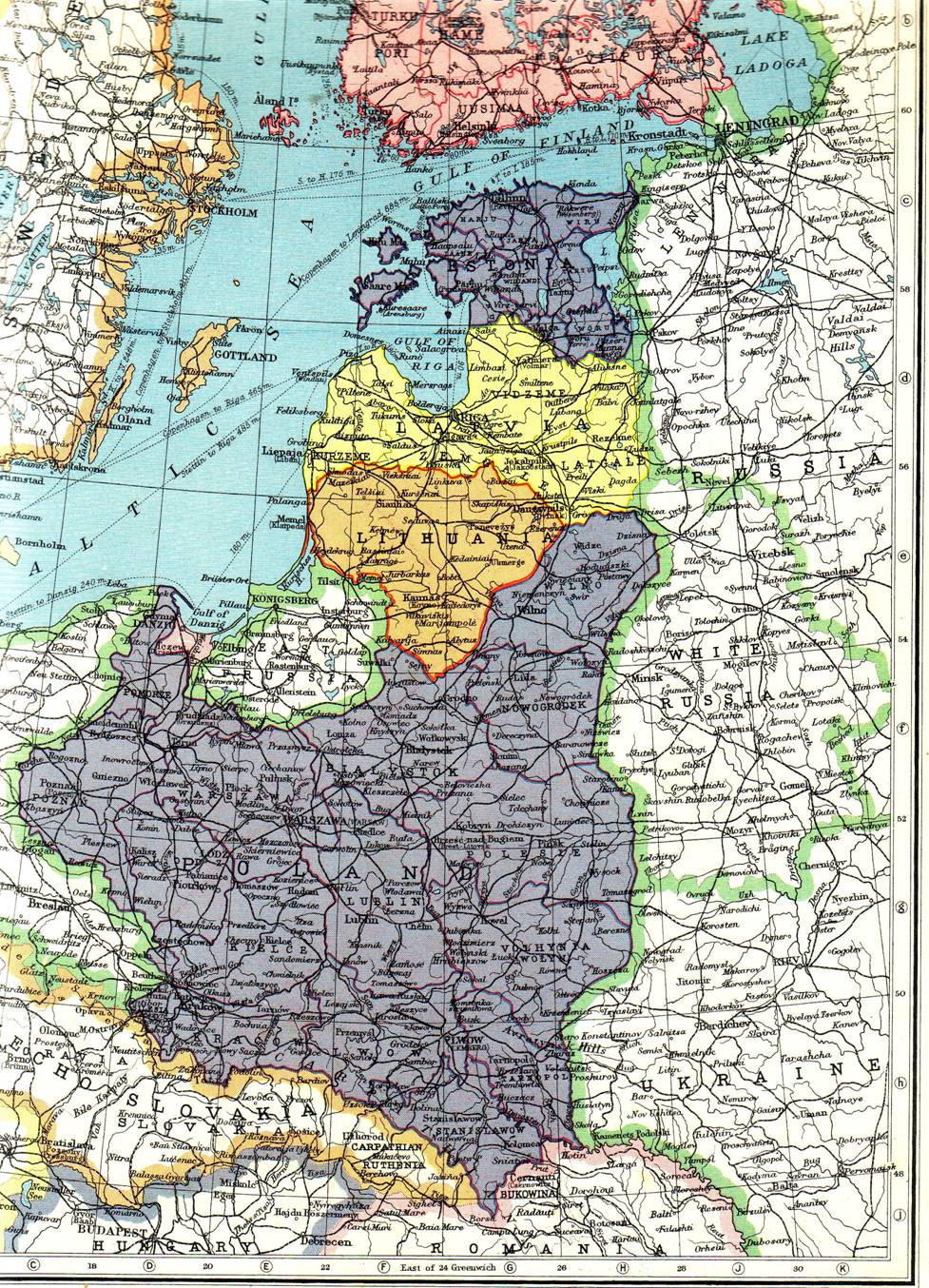

Click on the map for

better resolution:

Interwar Poland.

(i) Politics.

Polish political life

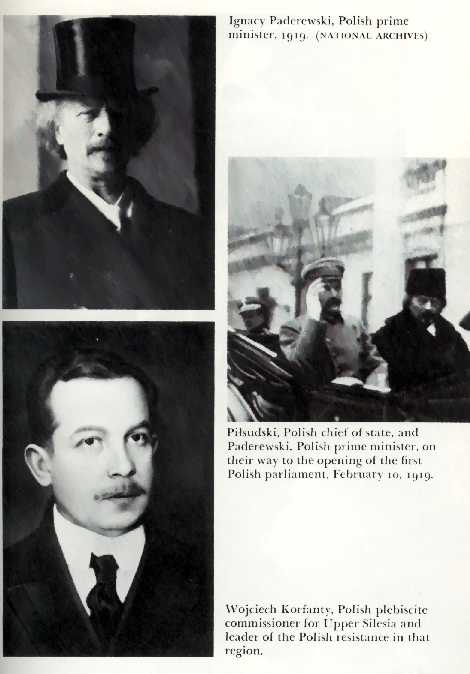

was dominated in 1918-23 and 1926-35 by Jozef

Pilsudski (1867-1935), but he was bitterly opposed by his rival, Roman Dmowski (1864-1939), leader of the National Democratic movment. This was a right wing, Roman Catholic and anti-semitic movement supported by a significant part of the

Polish intelligentsia [educated people of gentry

descent, mostly in the civil and military service but also in the liberal

professions] and the growing middle class [business people, entrepreneurs].

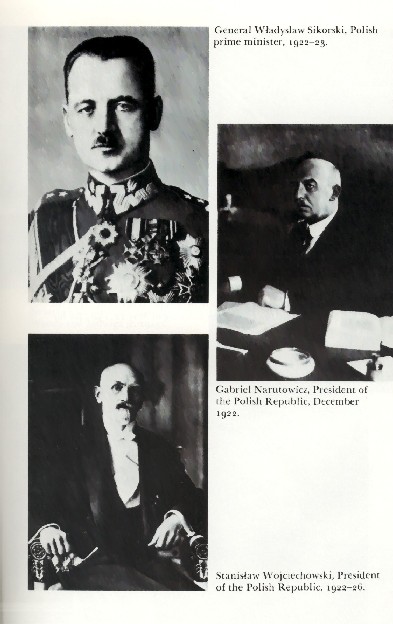

Pilsudski was "Head of State" until December 1922, when the Seym [Parliament] elected the first President, Gabriel Narutowicz (1865-1922) after

Pilsudski had declined the post because it had no power. Narutowicz,

an engineer and former minister, was supported by Pilsudski. His election was

bitterly resented by the National Democrats because he had won the presidency

in a Seym[parliament]

election with the votes of deputies representing the national minorities,

including the Jews who made up 10% of the whole population. Therefore, the N.

Democrats claimed that Narutowicz was not a Polish

President and incited the

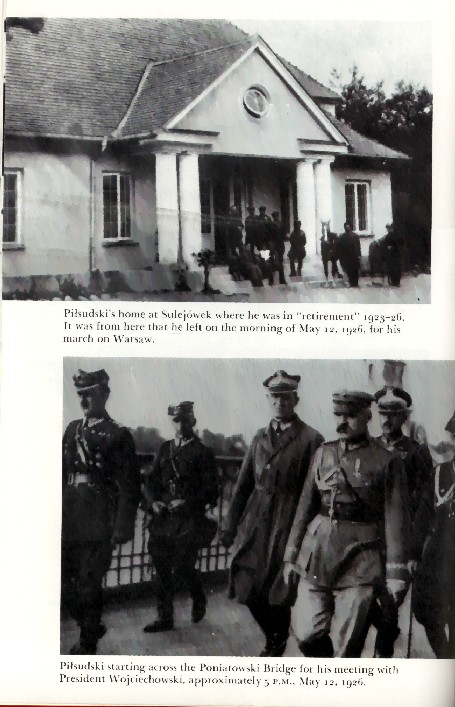

[Pictures from Richard M.Watt,

Bitter Glory, New York, 1974].

The Polish political

system, as it existed in 1921-26, was modeled on

The multi-party

system was the source of political instability because, unlike the French model

which included a professional bureaucracy unaffected by changes of power

(except for ministerial positions), in Poland most of the civil service jobs changed

hands with each new government, which distributed them as political patronage.

(As in most East European countries, the civil service employed most of the

country's Intelligentsia, or educated people). In 1923, a National

Democrat-Peasant Party coalition politicised military appointments, which Pilsudski protested by

resigning from all his positions in July of that year and going into

retirement. He distributed his marshal's pension to charities and lived from

his writings and lectures.

The years 1923-24

witnessed great economic- financial instability in

Recovery seemed in

the offing with the establishment of a new Polish currency, the zloty (meaning

golden), in 1924, but a year later

The situation was bad

for

†

In fact, these treaties of mutual assistance weakened the existing French

alliances with Poland and Czechoslovakia.. Pilsudski

was especially worried that

Pilsudski's Coup d'Etat, May

12, 1926.

Against the

background of this insecurity, in spring 1926 Prime Minister Wincenty Witos

(1874-1945), the leader of the right wing Peasant Party "Piast", entered into a coalition with the National

Democrats, and publicly dared Pilsudski to take power. Witos even threatened to establish a right-wing

dictatorship of the N.Dem. and

Peasant Parties, while the N.D. leader Roman Dmowski

was thinking of a dictatorship along Italian lines (Mussolini).

Pilsudski had the support of the Socialists and the Left-wing

Peasant Party in opposing a right wing dictatorship. He demanded that the

President dismiss the government and appoint a new one, and he threatened to

use military force to this end if necessary. On 12 May 1926, when he marched on

It should be noted

that Pilsudskiís action was not a classic military coup because he had the

support of Polish socialists and even the communists, who feared a right wing

coup. Indeed, except for the

†

|

|

|

*[Pictures from Watt, Bitter Glory. For a detailed

Pilsudski denied that

he wanted to be a dictator, and said his goal was to bring the country back to

health. This was the origin of the name given to his political group: "Sanacja" (pron. Saanatsiiaa,

from the French assainir = to heal). His main

objective was to give the Presidency strong executive power. He managed to

expand presidential power with parliamentary support in 1926-27, but when

parliament opposed him, he appointed governments of "experts" which

issued decrees on the assumption that parliament would approve them. When

parliament resisted, tensions grew. Pilsudski was twice Prime Minister, but

devoted most of his attention to defense and foreign affairs. He was the

Inspector General of the Armed Forces and Minister of War from 1926 until his

death in May 1935.

In 1927 a pro-government

bloc was created, the" Bezpartyjny Blok Wspolpracy z Rzadem." (The

Non-Party Bloc of Cooperation with the Government, known by its acronym: BBWR.

In fact, it was created to balance the N.Dem. "Oboz Wielkiej Polski"

(Camp of Great Poland -OWP), created by Dmowski in

1926 as an umbrella organization for various right wing parties affiliated with

the N.Democrats.

Political tensions

worsened under the impact of the Great Depression which hit

The imprisonment and

trial of political opponents was a black mark for

In April 1935,

Pilsudskiís supporters used a trick to pass a new constitution. The

opposition deputies were not told when the vote would be taken and most were

absent. (Pilsudski expressed his disapproval of this trick). The "April

Constitution" gave very extensive powers to the president. (Some

historians compare Pilsudski with Charles De Gaulle, who obtained

extensive presidential powers in

Pilsudskiís

successors continued the political system

established by the April constitution. They controlled parliament and passed a

new electoral law (July 1935), which allowed the government party to hand pick

deputies to run for parliament. In reply, opposition parties boycotted the next

elections.

The post- Pilsudski

governments are sometimes called "the governments of colonels,"

but they were not military juntas in the Latin American style. They consisted

mostly of politicians who had served in Pilsudskiís Legions in WW I and held

the rank of colonel, though the vast majority were colonels in the reserve.

Their program was the same as Pilsudskiís: to make

In 1937, the BBWR was

dissolved and replaced by the "Oboz Zjednoczenia Narodowego"

(OZON = Camp of National Unity), led by Col. Adam Koc.

OZON made anti-semitic gestures to gain the National

Democratsí support for the government. However, it did not go far enough for

the N. Democrats, for unlike Romania and Hungary, no anti-Jewish legislation

was ever passed in Poland, except for the prohibition of Jewish ritual

slaughter of animals (which continued anyway because Polish butchers

would have gone broke without Jewish purchase of beef). The restriction on

Jewish student enrollment called the "numerus clausus" or closed number, was

not sanctioned by law (see under minorities below). Nor was OZON effective in

building up popular support for the government. In fact, the Municipal

Elections of December 1938 returned many oppositionists. President Ignacy Moscicki

(1867-1946, pron: Eegnaatsy

Moshtseetskee, President 1926-39) promised electoral

reform, but it was not implemented because the government party did not want to

share power with the opposition..

The second most

important person in the state after the President was the Inspector General of

the Army, Marshal Edward Rydz-Smigly

(or Smigly- Rydz,

1886-1941, Marshal November 1936), but he was not a politician. However,

he did support the modernization of the Polish Army, which began in earnest

after Pilsudski's death.

The key foreign policy maker was Foreign Minister Jozef Beck (1894-1944,

For. Minister

1932-39), hand picked

for the position by Pilsudski. He had been a Pilsudski legionnaire in World War I, and served in

Military Intelligence, 1920. In the early 1920s he was Military Attache in

As Foreign Minsiter, Beck followed Pilsudskiís policy of maintaining

the alliance with

The National

Democrats, the Socialists, and both the left and right wing Peasant Parties

were in the opposition after 1928, and boycotted the elections held under the

electoral law of July 1935. Nevertheless, they retained and even gained

followers.

†

There was a small fascist group, the "Falanga."

that split off from the N. Democrats, It was led by Boleslaw Piasecki who admired Mussolini and was strongly anti-semitic. But this group was insignificant in Polish political

life. (Piasecki served Polish communist governments

after WW II).The majority of Pilsudskiites

successfully resisted the idea, advanced by a few of their number, of

establishing a dictatorship along fascist lines and Pilsudski never envisaged

it.

(ii)Interwar

Like most countries

of E. Europe,

†

(b) in the 1920s Gt.

Nevertheless, the Poles managed in just a few years to integrate the economies

of Russian, Austrian and Prussian Poland and to create a uniform legal system,

which was no mean achievement. Furthermore,

(1)

(2) †

In 1939,

(3) †

The city of

[ Many foreigners, mostly English and

German, were guests in our home, and I remember seeing father off at the

airport on some of his business trips. I also remember being taken by him to

visit an English merchant ship, which had a Chinese cook with a pigtail, and the new Polish ocean liners of the Gdynia-America

Line, which sailed regularly on the

[

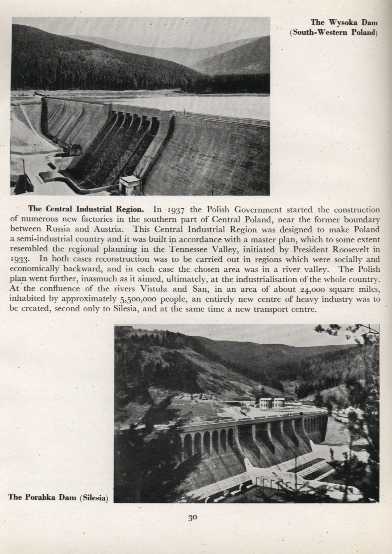

(2). The other great economic development of interwar

[

Land Reform.

In 1919, 35% of the

arable land in

The Great Depression, which hit Europe in

1930, lowered the price of agricultural goods while at the same time the rural

overpopulation could not be absorbed by

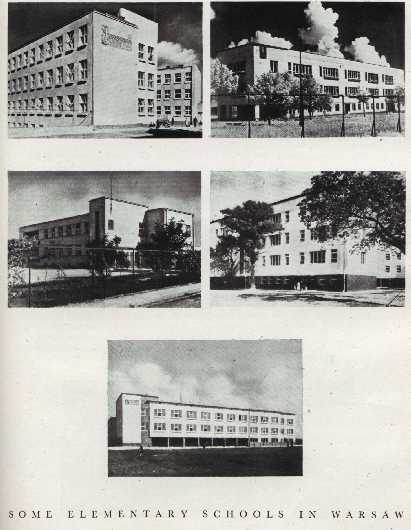

Education.

There was great

progress in this field due to free and compulsory education at the primary/

elementary and middle school levels, so tha tilliteracy was almost wiped out by 1939. There were 28,000

primary schools and 770 secondary schools, but only one High School was free of

charge. By 1939,

[

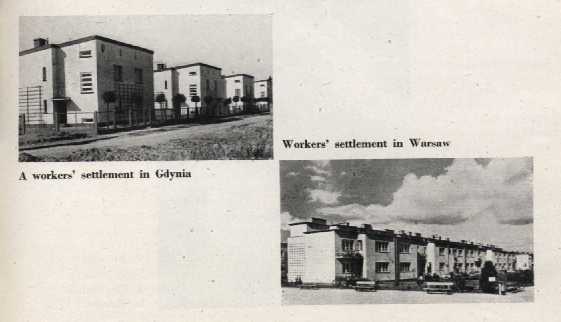

Social Services

These were very good in the towns. Workers paid a little

toward medical care while employers paid the rest. There was also government

subsidized housing for the workers. However, with the onset of the depression,

unemployment grew, as it did elsewhere in Europe and the

[

Women.

A few educated Polish

women had begun to go into other professions than school teaching before 1914.

In the interwar period, there were Polish women doctors and dentists, also

engineers and architects, but they were still a small minority compared to

men. There were some Polish policewomen, mainly directing traffic. There

was also voluntary paramilitary training for women. Women had the right

to vote since the rebirth of the Polish state in November 1918.

[

The Arts.

The interwar period

saw a great flourishing of art, literature and theater in

While only the

composer and musician Karol M. Szymanowski

(1882-1937) and the great pianist and composer Ignacy

Paderewski (1860-1941, Prime Minister, then Foreign Minister January

-November 1919), managed to attain world fame, there were many other great artists

and writers who are still recognized and admired by Poles today.*

*[For literature and

theater, see: Czeslaw Milosz, The History of

Polish Literature London, 1969, and reprints, chapter X, Independent

Poland. On the arts, see: Janina Hoskins, Visual

Arts in Poland. An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Holdings in the

Library of Congress, Library of Congress, Washington, 1993; the vast majority of the works listed here are

in Polish].

(iii) Minorities

As mentioned earlier,

national or ethnic minorities amounted to some 30% of the total population.

This was one of the problems faced by the Polish state, but it was not a major

problem, and was certainly less serious than that faced by the multinational

states of

According to

the last prewar census, held in 1931, the nationalities inhabiting

by mother tongue

|

|

|

|

|

In millions |

|

Polish |

21,993,400.....

....68.9% |

|

Ukrainian |

4,

442,000.*.13.9% |

|

Jewish |

2, 732,600*...... 8.6% |

|

Belorussian |

990,000......... 3.1% |

|

German |

741,000*...2.3% |

|

Russian |

139,000..........0.4% |

|

Lithuanian |

83,000..........0,3% |

|

Czech |

38,000...........0.1% |

|

"Local"(tutejsi)** |

707,000..........2,2%

|

|

Others |

11,000..........0.1%.

|

|

TOTAL |

31,916,000........100%

|

[*disputed figures; ** locals]

adjusted by religion

|

|

|

|

Polish |

20,644,000.........64.7

% |

|

Ukrainian |

5,114,000 ........ 16

.% |

|

Jewish |

3,114,000............9.8%

|

|

Belorussian |

1,954,000...........6.1%

|

|

German |

780,000............2.4%

|

|

Russian |

139.000............0.4%

|

|

Lithuanian |

83,000..............0.3%

|

|

Czech |

38,000...............

0.1% |

|

Local.(tutejsi)* |

- - |

|

Other |

11,000...............0.1%

|

|

Not

given |

39,000..............0.1%

|

For the official figures according to mother tongue. see the Concise Statistical Yearbook of

For the figures given in the second table, as adjusted by Professor Janusz Tomaszewski in his book

about the multinational

* Local (tutejsi) was declared mostly by people living in

The total population

of

The Germans

lived mostly in western

The Ukrainians

lived in former

Some west Ukrainians

had fought the Poles for an independent Ukrainian state with its capital in Lviv (P. Lwow) in 1918-19 and

lost, leaving bitter feelings on both sides. Some Ukrainian intellectuals

emigrated to Soviet Ukraine and participated in the cultural renaissance there

in the early 1920s, but most were later imprisoned or killed in Stalin's

crackdown on "nationalism" which began in 1926. Later, millions of

Ukrainians died in Stalin's man-made famine of 1930, which he used to break

Ukrainian peasant opposition to his collectivization of agriculture. Some

Ukrainian exiles lived in

The official leader

of Ukrainians in

The Ukrainians had many elementary and middle Ukr.

lang. schools, and developed a network of highly

prosperous cooperative shops selling agricultural produce. They had legal

political parties whose deputies were elected to the Polish parliament.

However, there was an

extreme nationalist organization, the OUN (Organization

of Ukrainian Nationalist), established in

In September 1930, the OUN launched organized attacks on Poles in East

Galicia with the aim of causing a mass Ukrainian uprising. They burned Polish

manor houses and villages. Pilsudski sent in the army which carried out a

brutal "pacification." The number of

Ukrainians killed was small, maybe 50, but Polish police mistreated the

population and destroyed Ukrainian property and libraries. This, of course,

increased Ukrainian resentment of Polish rule. Ukrainian

discontent and even resentment of Polish rule is understandable, but we

should bear in mind that the Ukrainians living in the

The Belorussians were divided between Roman Catholic, Uniate,

and Greek Orthodox, and did not have a strongly developed national identity.

However, grinding poverty lent appeal to communist propaganda, so the

Belorussian peasant party "Hromada," established

in 1925, cooperated with the Belorussian Communist Party, an affiliate of the

Polish Communist Party. Therefore, the Hromada was delegalized in 1927; its leaders were tried in

The Jews of

Most Polish Jews were

orthodox, that is, Hasidic Jews. Most were poor and worked in crafts and

retail trade. Some were money lenders in small towns and villages, mainly in

the central and eastern areas which had been former Russian Poland and the

southern areas which had been

Jews and Poles had

lived alongside each other for centuries, but in separate communities. Thus,

they lived together but apart. The Jews preserved their identity through their

religion, customs, and languages (Yiddish and Hebrew), but this obviously

differentiated them from the Poles, as well as Ukrainians, Belorussians,

and Russians.

Assimilated Jews made up some 5 % of the whole Jewish population of about

3,500,000 (1939), but they gave Poland many outstanding writers, poets,

lawyers, doctors, and scientists. Indeed, these assimilated Jews constituted

some 25% of the Polish intelligentsia as a whole. Those educated before

1918, dominated the legal and medical professions and this incited right-wing

government coalitions in 1923-26 to attempt passing legislation restricting the

intake of Jewish students of law and medicine to 10%, roughly equivalent to the

percentage of Jews in the total population. This was called the "numerus clausus" or closed

number. However, attempts to make this into law failed, so its application

depended on university administrations. Nevertheless, Jewish students were

generally not admitted to study medicine and law.

[Note: At this time, a 10% admission ceiling for Jewish students was the

unwritten rule at Harvard, and probably other Ivy League Universities as well].

N.Democratic students frequently attacked their

Jewish colleagues, or restricted them to back benches, but the extent to which

this was practiced depended on the university administration.

Quite a few members

of the assimilated Polish-Jewish Intelligentsia was politically

left-wing and sympathized with Communism or joined the Polish Communist

Party, whose visible leadership was preponderantly Jewish. This added fuel to

the N.Democratic brand of anti-semitism.

Finally, there were very few Jews in the Polish civil and foreign service, except for a few totally assimilated Polish

Jews. There was one general (Mond) of Jewish origin

in the army, but most Jewish officers - 10% of the officer corps - were in the

medical branch of the service.

It is worth noting

that the Jews of

*[For a photographic record of Jewish life in

After the Depression

hit, the Polish government sought to reduce the number of Jews in

*[See Laurence Weinbaum, A MARRIAGE OF

CONVENIENCE. The New Zionist Organization and the Polish Government, 1936-1939,

East European Monographs No. CCCLXIX (369), Boulder Co. and

The Polish government

tried to find areas of settlement for Polish Jews in French colonies,

especially

Conclusion.

The treatment of minorities in interwar

But despite the injustices, despite the terrorism by

the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and the counter-terror

resorted to by the Polish State, despite the systematic Polonization

of the school system and conversion of Orthodox churches into Roman Catholic

ones under phony pretexts, despite numerus clausus and the exclusion of Jews from the professions

- despite all this and more, the material, spiritual, and political life of the

national minorities in interwar Poland was richer and more complex than ever

before or after.

In support of this claim, the author cites the

following statistics: in 1931, there were in Poland 920 Jewish non-periodical

publications, mainly in Yiddish,but 211 in Hebrew;

342 Ukrainian non-periodical publications, of which 264 appeared in the Lwow (Líviv) voevodship;

and 33 Belorussian non-periodical publications in the Wilno

(Vilnius) voevodship. Wilno

was the second most lively Jewish publishing center

after

*[Jan Gross, Revolution from Abroad. The Soviet Conquest of Polandís Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia, Princeton, N.J., 1988, pp..6-7. Here, the

author also cites 1939 Ukrainian, Jewish and Belorussian publication figures

for the territories annexed by the

††††††††††† Originally

published at http://www.ku.edu/~eceurope/hist557/lect14a.htm††

|

|

Anna M. Cienciala

B.A. Liverpool, 1952, M.A. McGill, 1955;

Ph.D. Indiana, 1962 20th century Polish, European, Soviet, and

American diplomacy 1919-1945. Born in the Free City of Danzig (Gdańsk, in Poland after WWII); she attended middle and high school in England; university studies in England, Canada, and U.S. (B.A. Liverpool, 1952, M.A. McGill, 1955; Ph.D. Indiana, 1962). She taught at the University of Ottawa and the University of Toronto before coming to the University of Kansas in 1965. More info |