|

|

The

Soldiers of Georgia

in Polish Service (1923 -

1939)

by Dmitri Shalikashvili (translated by

Maria Shalikashvili)

Photographs graciously donated by

George Nikoladze

Click here to see the

movie “The Story of Georgian Officers in Polish Army”

(in

Polish with English subtitles)

|

The

refugees that left Georgia after she had

been conquered by Russia in 1921, landed in Constantinople. Most of them

did not stay there long. A small group returned to Georgia, while the majority decided

to try their luck in other countries. Constantinople

offered no opportunities to settle down and make a living. The Georgian

refugees left that city heading for different countries. Some chose France, some Germany,

some Poland.

They settled down in these countries and the[ir] environment, as well as the

living conditions, had a definite influence on the respective three groups.

They took up the culture and different customs of the countries they lived in.

For

example, in France, our Georgians

concentrated in Paris

and became the center of the Georgian political life in exile. Paris

also became the cultural center of our Georgian emigrants in France. As they

lived in Paris

and other big cities, among the French people, the Georgians absorbed the

French culture and customs of the land. They also learned the French language.

However, it was not easy to find jobs that would correspond to the education

these emigrants had received at home. So they had to content themselves with

whatever work they could find. Most of them had to work in factories, become

cab drivers or help in grocery stores. But among all these hard working people.

who had to struggle for a living, there were many who managed to dedicate their

time to politics and to constructive ideas that could help their countrymen in

exile. Quite a few young Georgians were accepted to French military schools and

after having graduated from them, became officers in the French Army. They

served in the Foreign Legion in Africa. All of

them enjoyed an excellent reputation and many became outstanding officers of

the French Army. One of them, Prince Bazorka Amilakhvari, covered himself with

glory serving in the Foreign Legion. My brother David also joined the Foreign

Legion. He was a colonel in the Georgian Army, but had to start as a

second-lieutenant in the Foreign Legion. David served during the Morocco

Campaign and was promoted to lieutenant. After 15 years of service, David

retired in 1939, but as World War II began he was called to active duty again,

and was promoted to captain and assigned as commander of a Reserve Battalion of

the Foreign Legion, stationed in France.

The

Georgian colony in Germany

was rather small, but quite outstanding. The Georgians were lucky to settle

down in a much more comfortable way than the Georgians in France did.

They found good, well paid jobs. The young people were accepted to German

universities and among them quite a few graduated with Master's and Doctor's

degrees. Some became professors or worked in research. Several Georgians chose

the scientific field, in which they became quite prominent.

Completely

different was the situation for Georgians who came to Poland.

Different from the group that went to France

and also from the one that chose Germany.

The

majority of Georgians were accepted into the Polish Army, and thus could no

more be considered immigrants. They became part of the Polish society which

accepted them fully and without reservations. The Georgians in Poland lived a

perfectly normal life, sharing all the privileges of the military and enjoying

an excellent relationship with their Polish fellow officers. It has to be

stressed that the Georgians were received with open arms, as brothers, and

welcomed very warmly. Poland

that was under Russian rule for over 100 years, well understood the tragedy of

the Georgian people, and the Polish authorities were trying hard to please

their Georgian friends.

However,

despite the fact that Georgians were received so warmly in Poland, they

never lost their identity. We did not dissolve in the melting pot of the

country. We stayed Georgian patriots and thank God for that! Georgians could

proudly say that Georgia

was their native land and will remain such forever. They served Poland faithfully and will always be grateful

for the warm hospitality Poland

extended to them. However, they stayed Georgians and kept praying for the day

the could serve their country again, fight under Georgian banners.

How

very different the three groups of Georgians really were, could be clearly see

when World War II broke out and each of the groups took a different stand.

Fate

has been very kind to me and I truly consider it a blessing that I was chosen

to join the group of Georgians that were received by Poland. Not only do I feel a great and

most sincere admiration toward the Polish people, but also I found my personal

happiness in meeting my future wife in this country. I honestly believe that

Missy and I were one of the happiest couples in the world, devoted to each

other and understanding one another in absolutely everything. In describing the

life of the Georgians in Poland,

I will try to give a full picture of the land, the individuals with whom I

worked, the activities I participated in, as well as the life of an officer in

the Polish Army. The historical and political events of this particular time

were certainly very interesting, and I shall try to introduce the reader of

this book to the many details of that period of time; the brilliant years of

the young, independent Poland,

the many outstanding personalities of that time, but most of all the life of

the military. Due to the fact that I love Poland so dearly and served in the

ranks of the Polish Army that I honestly consider one of the best in the world,

I remember everything very clearly. The wonderful years I spent in Poland, the

great happiness I experienced during those years, will stay in my memory

forever! Even small details have not escaped my memory. I remember it all and I

love it all, every minute of it! Poland and the Polish people will

always stay very close to my heart. I served in the Polish Army and have the

highest esteem for the Polish soldier. The Poles are good, warmhearted, kind

and honest. They are very brave, love their native land and are ready to

sacrifice their lives for their country at any time. Polish people are true

patriots and deeply religious people. I am very grateful that Poland extended

such a warm hospitality to us, Georgians, and accepted us as equals, allowing

the Georgian officers to join the Polish Army. Thus, we were not feeling

immigrants in a new country. We were invited to work and to share, to

participate in everything.

[As

for me], I could continue the military career I had chosen. I also had the

possibility to graduate from the War

College.

I

lived in Poland

over 20 years and can honestly say that those were the happiest years of my

life.

I

met my wife in Warsaw.

She was raised in Poland

and considered herself Polish, not Russian, [which] she really was. Poland was her second

Fatherland that she loved deeply. We both were young, full of energy, in

excellent health. We lived a happy, most wonderful life, sharing all our

thoughts and making plans for the future. We were surrounded by true and

warmhearted friends and lived an interesting and full life of beautiful

experiences and joy! This is how I shall always remember the years I spent in Poland: happy,

interesting, productive years!

Our

Georgian group left Constantinople on November

12 [1922], by ship that took us to the Romanian harbor Constanza. The food on

this ship was expensive, so we had nothing to eat. Besides, a terrific storm

started as our ship left Constantinople. There

were no beds or cots to sleep on, so we spread out our blankets and cuddled up

on them, shivering from the cold! From Constanza we proceeded to Bucharest by train. We

stayed in that city one day, waiting for an adjoining train to Warsaw. We arrived [at our] destination on

November 21, and were greeted by representatives of the Georgian Colony. The

chief of our group, General Kazbek, took us all Georgian officers to the

General Staff, in order to introduce us and to obtain further orders. There we

were greeted in a very cool manner, as they did not expect us so soon, and

seemed not to know what to do with us. It looked like the authorities did not

even known that we were supposed to come here, from Constantinople!

However, there was no question about sending us back. After some insignificant

formalities, our group was assigned to the Officers' School located in Bydgoszcz. The name in

German was Bromberg, but it was changed after Poland became independent. In this

school we were to complete a special course that was to acquaint us with the

service in the Polish Army. This was a temporary arrangement that lasted a

little over a year. It was replaced by permanent orders that read that the

Georgians would be accepted as officers in the Polish Armed Forces.

When

we left Warsaw, the chief of our group, General

Kazbek, stayed behind, being assigned to teach at the Military

Academy in the town of Rembert[w, and it was

General Koniashvili who became our chief.

We

arrived in Bydgoszcz

at dawn and were greeted by Captain Wojciechowski who would be the man to

coordinate all our activities and direct us in our work. Our quarters were

prepared in the barracks of an artillery regiment. We stayed in Bydgoszcz eight months,

until July 23, 1923, when we graduated from a shortened orientation course.

For

us, Georgians, there was a program designed to acquaint us with [the] tactics

of war, based on experience of World War I and the Polish-Russian war [of

1919-1920]. In the classrooms we had to learn the military history of the

Polish Army. We also had to study the Polish language and military terminology.

There was quite a bit to know about the political life in the new [and]

independent Poland.

We were given refresher courses on general military history. In a word, it was

an excellent school; and as we graduated, we were very well prepared to serve

in the Polish Army. The head of this Officers' School was General Jacielnicki.2

He was a former officer of the Imperial Russian Army, graduate from the War College

in St. Petersburg

and spoke Polish with a strong Russian accent. An outstanding officer, a very

good man, strict but just and fair.

Captain

Wojciechowski was also an officer of the old Russian Army.

What

helped us, Georgians, was the knowledge of the Russian language; thus Polish

was not hard to learn. However, both these languages, being related, sometimes

confused us.

Our

schedule was very demanding and kept us working hard. Myself, I found

everything very interesting, as I was very fond of military sciences and was

eager to learn as much as possible. Even as a child, my dream was to become a

military man, and I never could think of any career that would better suit me.

As

a young man I never had the chance to graduate from a military school, and I

was promoted to officer's rank for my achievements on the battlefront during

World War I, when I also received the medal of St. George.

Now,

in this Polish school I had the opportunity to learn about strategy, tactics

and other military matters. I must admit that I was learning with great

enthusiasm! I truly plunged into military science with one desire only: to

graduate with honors from this first military school I was lucky to be admitted

to! I spent all my evenings reading military literature. And I am truly

convinced that after having graduated from this course, I knew more than many

officers know, after they graduate from regular military schools. This was

because of my desire to learn and absorb as much as I possibly could. Now I

knew that I was well prepared for the career I was dreaming of, it being the

true purpose of my life!

The

fundamentals I learned in Bydgoszcz helped me a

great deal in the military service, as well as prepared me very well for other

military schools I attended later, including the War College.

In

this school in Bydgoszcz

we had to wear private's uniforms to classes, but we wore civilian clothes for

the rest of the day. It has been pointed out to us that we have not yet been

accepted into the Polish Army, but that we certainly had the chance of being

accepted later. Right now we were [in school] on a temporary basis, and all

depended on our performance. We were receiving officer's pay according to our

ranks in the Georgian Army. We had to pay for our meals, but managed to save up

for recreation and small personal expenses. Bydgoszcz was a medium-sized town with all

the characteristics of a German garrison. Very clean, very proper and dull! The

population was predominantly German, but there were many Polish families that

came to live here.

At

that time Poland

was suffering a very difficult economic crisis and money was losing its

purchasing power literally from day to day. In the very worst situation were

people who had their money tied up in bank accounts, and individuals on fixed

income. As to the military, we were in a somewhat better situation. When prices

were going up, we were getting a salary increase automatically. At that time we

were receiving our paychecks every two weeks, and when we got the money we

spent it in just hours! The prices for everything were going up from one day to

another, so it was imperative to stock up on supplies. This economic crisis

lasted until 1925 and ended only when the current money was replaced by new

currency at a rate of one zloty to 1,800 Polish marks! Naturally this was a

very bitter pill to swallow, but it helped. Such a drastic measure saved the

economy. The inflation was crushed and the country could regain strength. This

inflation in Poland, even if

severe, was by far not as bad as the one in Germany. Prices there were going up

literally every hour and I have seen myself an envelope with stamps on it for

one million German marks!

As

I have mentioned before, the chief of our Georgian group was General

Koniashvili....He loved to speak of his stay in St. Petersburg, where he had a good time. And

no wonder: the dashing, handsome Georgian, temperamental as he was, covered

with glory as the conqueror of the Turks, at the fortress of Erzerum, he

certainly had all chances to be noticed, admired and celebrated!

Koniashvili

returned to the Caucasian Front and served there until the Russian Revolution

of 1917. But, ironically, Erzerum once more played a significant part in his

life. However, this time it was a completely different part than the one

before. Shortly after the Revolution of 1917, Koniashvili was arrested and sent

to Erzerum for trial. He was sentenced to die by the firing squad....[author's

ellipsis] So now he was awaiting death in a prison in Erzerum! But fate was

merciful to him and he managed to escape. For a short while Koniashvili stayed

in the adjacent woods and by watching the stars, he was trying to find his way

toward the North. After several days of hiding, he took a terrific chance in

boarding a train on a small station. Luckily for him, he was not recognized.

Without further adventures, General Koniashvili reached the capital of Georgia, Tbilisi.

Only then did he feel himself in safety. As Georgia

was declared an independent Nation, General Koniashvili was offered the

position of Commander of the new Georgian Army on the front of Sochi.

However,

here, this army under his command suffered a defeat. The White Russian Army,

under the command of General Denikin, took Sochi. Thus, in a sad and unexpected way, the

military career of General Koniashvili came to an end. While telling us of this

sad page in his career, Koniashvili never liked to dwell on the military defeat

his army suffered. He preferred to remember the good times he had in Sochi, the parties, the

drinking, the beautiful women and himself enjoying all the attention of the

crowd!

After

the defeat of the army entrusted to him, Koniashvili could no longer expect to

receive a significant assignment. He became Chief of the militia of the City of

Tbilisi. To his

credit, it should be said that he did an excellent job in organizing that young

and inexperienced force. His very last assignment in Independent Georgia was

Chief of Staff of the National Guard. After the Russians captured Georgia, he left for Constantinople and later,

came to Poland.

Now, General Koniashvili was with us in Bydgoszcz,

where he was very popular with the Polish officers and warmly loved by us,

Georgians.

Besides

having lectures in classrooms, we also had field exercises. In the area there

were many places adaptable for such exercises. We were supervised by Captain

Wojciechowski. As we marched we were supposed to sing, but not yet knowing the

Polish songs, we were singing our Georgian songs, much to the amazement of the

town's people who were staring at us and wondering!

I

came to Poland

during one of her most interesting times, historically and politically. After

more than a century of being under foreign rule, Poland became an independent

country and started to live a new life of freedom. What actually happened can

be justly called a miracle; as in order to become a free nation, Poland would

have to fight with the three great powers that had a grip on her, and this she

certainly could not do. The miracle that happened was that all three powers

crumbled at the same time and consequently Poland had the chance to set

herself free. That moment came when, during World War I,

Russia, Germany and Austria, fighting on respective

sides, but undermined by revolutions, suffered defeat and lost their power for

a long time to come. Soon after World War I broke out came the Russian-Polish

war. After having defeated the Russian troops, Poland re-established relations

with the new Russian regime and got back the land that had been taken away from

her by Imperial Russia.

Both

Germany and Austria, being defeated by the Allies, were

forced to accept the decision of the [Allied] Coalition and give Poland back all

lands previously taken from her. Germany

and Austria were advised by

the Coalition to sign peace [accords] and the agreement to establish an

independent Poland.

Now

comes the question: why did the Coalition do that and what advantage did it

have in establishing an independent Poland? The answer could be, that

the Western world was afraid that Germany, after having recovered

from her defeat, could stand up on her feet again and thus become a new

potential threat to peace. In other words, Germany might go back to her old

politics of aggression. As a result of such fears for the future, the Coalition

decided to weaken Germany

and to found a dependable ally in Eastern Europe.

The idea was to surround Germany

and for that purpose Poland

and Czechoslovakia, both

eager to become free countries, were helped to establish their Independence. However,

such politics proved to be rather unwise and short-sighted, as these new

countries were strong only as long as Germany was weak. The very moment

she stood up and was ready for aggression, she decided to fight, and the

Germans pledged a bloody revenge directed toward both England and France. As Germany stood up, this time well prepared for a

new war, and the struggle began, the young and inexperienced countries, both Czechoslovakia and Poland, simply crumbled and were

crushed by the strong aggressor! But, ironically, that erroneous and very

short-sighted way of handling things proved beneficial for Poland, as she

received the strong support of a potential friend of the Polish people, France.

That was important. However, it is sad that Poland

did not see how dangerous a mistake the Western world was committing by

underestimating the future strength of Germany. Poland started to act as one of the

powerful nations, which she certainly was not. Nor did Poland take

advantage of the time she had to strengthen her Armed Forces and to build her

Nation on a dependable foundation. But her biggest mistake was not to try to

make-up with her neighbor, Germany.

She made no effort to bring to an end the ancient feud and build the future on

a neighborly relationship. This big mistake proved critical and cost Poland her

Freedom.

There

were many political parties, both within [Poland] and outside its borders.

The role of these respective parties was very significant in how they

participated in the struggle for freedom. However, their approach was

different, depending on the political views of their leaders and their belief

as to what was best for their country. The most realistic and the only really

strong group was headed by Jozef Pilsudski.3 He was a truly unusual

man in every respect. Strong, courageous, a Polish patriot in the very best

meaning of the word. Ready for any sacrifices that his country would require of

him. Pilsudski was far-sighted, politically wise and broad-minded. He could

sense that Europe was heading for a war and

that this war would answer many questions. His opinion was that no matter how

strong the allies of Poland may be, Poland must be strong herself, must have an

excellent, well-equipped army to depend upon and, most important, be united and

prepared to join the family of great and strong nations. Jozef Pilsudski was

born in 1867 near Vilna [Wilno, Vilnius],

on the estate of his grandparents. The Imperial Russian government banished him

to Siberia for alleged anti-government

activities. Returning to his native country, after five years of exile, he

became the leader of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS). In 1900 he was arrested

again, but managed to escape to England.

When he returned to Poland

in 1902, he started secretly to organize a Polish army. At the outbreak of

World War I, he had over 10,000 men under arms. The government of Austria gave Pilsudski permission to train his

units in Austria.

The idea was that the all-volunteer troops could be used against Russia, in case

a war would break out. Understandably, Pilsudski was by no means led by

feelings of friendship toward Austria,

or her ally Germany.

He detested both countries just as strongly as he did Russia. His

idea was to organize Polish units that, in due time, would become the

foundation for a Polish army. This idea has been characterized by Pilsudski

himself as follows: "Poland

is ready to follow the devil himself, if he provides the Polish people with

weapons to fight for the freedom of their land." Pilsudski made his many

followers happy by organizing the Polish Legion, a strong unit that developed

into the Polish Army. This is where the name "Jozef Pilsudski's

Legion" came from. This happened in the city of Lwow [Lviv], seven years before World War I

broke out. Pilsudski's Legion was ready for combat, the great moment he was

waiting for came, his dream became a reality! So now, the first page of history

of the Polish Armed Forces was written, and the rapidly following events would

keep adding new pages to this new, still very young Polish history that was the

beginning of the declaration of independence of Poland.

Pilsudski

himself, as well as the movement he headed, the people he worked with, were all

closely associated with the leftist organizations of the land. These

organizations were related to the Polish Socialist Party. But this is quite

understandable, as the PPS was the political party that offered the strongest

resistance to the great powers that divided Poland. This party had many

underground fighters, not afraid of any persecutions. However, Pilsudski

himself was by no means a socialist and when the right time came, he did not

hesitate to cut all ties with the Polish Socialist Party and openly declare

that socialism is not what the Polish people like.

As

the Independence of Poland was established and the new government started to

form and function, different political leaders wanted to play an important

part, claiming their parties contributed to the struggle for freedom. Now they

all wanted to have a voice in the leadership of the young state. There were

three main political groups in Poland:

the PPS, Jozef Pilsudski's party, and the National Democratic Party. This last

one was a strong, right-wing party, with very conservative views. Even before

the war, this party was trying to find a compromise with the three great powers

that divided Poland.

The National Democratic Party avoided open confrontation and thus could not be

compared to the radical followers of Jozef Pilsudski who were not only eager to

fight in the underground and in the resistance, but also were radical in what

pertained to social reforms within their country. Pilsudski stood for a strong Poland, completely independent, a country that

would not bend toward any of the powerful neighbors, a Poland ruled by a strong

government, that knows best what is good for the well-being of the people.

Pilsudski was the one who called to life the victorious Polish Legions, the first

Chief of State that was recognized by the Allies, and the conqueror of the

Russians in that short but bloody campaign [of 1919-1920]. He was the idol of

the Polish Army.

But

despite all this, Pilsudski's role in Independent Poland was gradually diminishing

and faded completely at the end of 1925. It took a risky and highly dangerous

coup d'etat to restore his prestige and to put him back where he belonged, at

the steering wheel of the nation. The coup d'etat took place in May 1926. It

was arranged by his supporters and by his faithful army. The coup was widely

criticized by his opponents. A widespread controversy existed among the

population and the question was raised, was it moral to fight for power, when

the fighting was done by brother against brother and there was bloodshed on the

streets of the capital! Most likely this could not be morally justified.

However, one thing can be said in support of the coup, and that is, once the

reigns of power were once more in Pilsudski's hands, he succeeded to pull the

nation out of chaos and set it back on the right track. After he regained

power, his prestige abroad grew rapidly and Poland was treated will all the

respect, due to a strong nation.

All

the[se] historical events took place much later. Right now let us return to the

years before Pilsudski's star began to glitter. Let me say a few words about

the Polish emigrants that were living in France. Wherever Poles happen to

live, they remain good patriots and stay active politically. Living in exile,

in France,

they worked, preparing for the day their native land would become an

independent nation. However, strange as it may seem, once returned from exile,

they never got the chance to participate in the active political life of their

country. It was just as it should be: the new nation had to be built by the

people who never left her borders, who suffered with her through all the

calamities and worked underground, risking their lives and their freedom to see

her an Independent Nation. Those were the true sons of Poland and they

justly claimed the right to serve her, to work for her and to share with her.

The

political situation in Poland

was rather complicated and quite unique in many ways. In addition to the

different political groups that kept struggling for power and trying to disrupt

each other's work, there was still another factor that had to be taken into

consideration. Poland

was under foreign rule for such a long time. The three powers that have divided

the nation: Russia, Germany, and Austria, left an imprint on the

people who lived under the respective rulers, and now they had completely

different views and outlooks, customs and traditions. They all had to be united

and this was not an easy task. In normal conditions this could take years and

should be done carefully, using tact and a great deal of understanding. By

trying to hurry the process, many mistakes were made.

Here,

on these pages, I gave the reader a picture of Poland

at the end of 1922, when our Georgian group arrived from Constantinople.

Little by little, things were becoming clearer to us and we were familiarizing

ourselves with the complicated situation.

As

we landed in Poland,

a lot of things were extremely interesting to us and we liked to discuss many questions

among ourselves. Jozef Pilsudski became our hero, and everything that was

connected with him became of great value to us, his fans and followers. We were

spending much of our time studying the history of Poland and her military history.

Naturally

we also had time for recreation, we liked to go to a good restaurant or to the

theater. However, most of our evenings were spent with Georgian families, in a

cozy home atmosphere. In July 1923 we graduated. The final exams were very

difficult, but not one of us Georgians flunked these exams, despite [the fact

that] it was not easy for us because of the language.

After

graduating, most of us were assigned to other schools, according to our

specialty. Before starting the new schools, we all got one month's vacation.

The group of cavalry officers, and that included me, was assigned to the

Central School of Cavalry in Grudzi'dz. Thus, after graduating from the

eight-month-long course in Bydgoszcz, the first

period of my stay in Poland

was completed. This was a time when all of us Georgians lived as one big

family, sharing every joy, our hopes and our dreams. We were mostly socializing

among ourselves. All the Georgian families were offering warm hospitality to us

bachelors, and we were feeling at home with them, relating in an atmosphere of

friendship, happiness and understanding.

At

that time we had not yet warmed-up to the Polish families, who also did not

feel comfortable with us Georgians. However, taking into consideration the

language barrier, as well as some differences in customs, this was quite

understandable.

The

months I spent in Bydgoszcz

will forever stay in my mind as a very pleasant, most interesting time. I

learned a great deal, and being young and full of enthusiasm, I absorbed what I

learned and enjoyed everything. ....

It

was not Colonel Mochnacki who led the regiment to Warsaw to fight on Pilsudski's side [during

the 1926 coup d'etat]. It was Major Filipowicz. He was a Legionnaire and there

could be no doubt in his loyalty. As to myself, I had to stay behind, in

Ciechanow, being ill. But as soon as the doctor allowed, I joined the regiment

in Warsaw. I

was more than happy to be reunited with my fellow officers. The 11th Cavalry

stayed in Warsaw

for over a month, until things came back to normal and Pilsudski was in

complete control of the situation. Our regiment was stationed in Praga, just

across the Vistula

River from the capital.

We could visit our friends, in Warsaw

and in Praga there were restaurants and good theaters and night clubs. So when

the five weeks were over and we had to return to Ciechanow, we did so not

without regret!

Prior

to these historical events, none of us junior officers knew about Jozef

Pilsudski's plans for a coup d'etat. I presume however that some of the senior officers,

among them Major Filipowicz, did know.

Our

Division Commander, General Dreszer,4 a loyal Legionnaire and a

personal friend of Pilsudski, was known to have taken part in planning the

operation, and the truly brilliant performance of the 2nd Division certainly

was a major factor in assuring the success of the coup d'etat. General Dreszer

was certainly a man Pilsudski could count on. His devotion to the Commander of

the Legion was well known in Poland

and was beyond any doubt.

Soon

after the regiment returned to Ciechanow, we moved out on maneuvers. The second

squadron received orders to join one of the Infantry Divisions for combined

action in the region of Lomza. In later years, I had the opportunity to take

active part in organizing such joined actions and became sort of an expert in

that field.

There

were many memories connected with the Polish-Russian War, and some beautiful

stories told about the courage of individual soldiers and officers. There was

the legendary major Dabrowski, remembered as a fearless rider and partisan. His

way of fighting was non-orthodox and so different from any conventional way of

fighting, that it had a truly devastating effect on the enemy. His name alone

made people tremble with fear. In the Polish literature of that time, many

books were dedicated to the description of heroic deeds and how the Polish

people never hesitated to offer their lives to the country. The deeply rooted

hatred toward the Russians was so great, that women were joining the partisans

and even children served as messengers in the underground organizations. Quite

often they were captured by the Russians and threatened to be tortured if they

refused to give the names of the partisans. These children never betrayed the

secrets they were so proud to have been entrusted with, and preferred to die

rather than harm the common cause and their country. There are long lists of

women, girls and boys who accepted torture and died silently, never answering

the questions put to them under torture by the Russians.

I

honestly think that the Polish people are the best patriots in the entire

world, and this not just in words or fancy parades and military display of

troops, but when it comes to real sacrifices for their beloved land. The Poles

never hesitate to put their country first, completely disregarding themselves,

their loved ones, their families. Willing not only to die, but ready to be

tortured and meet death as martyrs. I truly am concerned that most of the world

does not even know what splendid people the Poles are. It is that spirit of

true patriotic love for their country that drives the Polish people to perform

such legendary deeds in the name of their beloved land, and they firmly believe

that Poland

is blessed by the Holy Virgin Mary, who guides them through sacrifices and

martyrdom to glory and greatness. .....

The

ability to express oneself clearly is one of the traits of the French. It can

also, to a certain degree, be said about the Russians, which can be noticed

when reading books on military subjects in either French or Russian. Russian

books that discuss difficult tactical problems are written in a clear, well

understandable manner. And this can be said about such books written before the

Revolution of 1917 as well as about the ones written after it.

In

this particular matter, both the French and the Russians differ substantially

from the Poles, who despite the excellent knowledge of the subject, tend to

present the plan in such a complicated way, that it becomes hard to follow what

it is all about.

It

certainly is imperative to give credit to the Polish officers of that

particular post-war time. Most of them were very well educated and truly good

officers. They also were full of genuine enthusiasm to serve their country, and

I can say this without hesitation that any other European Army would be proud

of having such excellent officers in their regiments. In my judgement, the very

best were the junior officers. They had just recently graduated from

officer-candidate school and came from highly patriotic families. They started

their military career with genuine enthusiasm. As to the senior officers, most

of them had served in other armies for many years. Quite often, they had

difficulty adapting themselves to the young Polish army, and sometimes did not

even fit in as was expected of them. As to the young officers, they really used

their knowledge with great zeal and earnestness, and their patriotic fervor

made the best officers of them. They were praised and admired by their

commanders, [and] they also knew how to maintain a great relationship of trust

and high esteem.

After

all these digressions, let me return to the General Staff Academy and to the

description of the two years I spent in this outstanding school.

As

I arrived in Warsaw, I was invited by my good

friend from Tbilisi,

Colonel Watchnadze, to stay at his apartment. It was very small, but his wife

and daughter were on vacation in France, so the Colonel asked me to

stay with him the two months they were gone. He was a very nice and kind man,

and his warm hospitality really touched me. However, I did not stay with him

more than three weeks and found myself a room not so far from school. It was

very conveniently located on Polna

Street.

Our

class was rather large. There were sixty Polish officers and three of us,

foreigners: Captain David Kutateladze, Colonel Israfil-Bey and I. There also

were two Polish medical doctors. They were on a somewhat different schedule, as

they did not have to attend all the lectures, and the ones they attended were

designated for supervisors of medical teams. These doctors were being prepared

for high-ranking positions in the Department of Health.

We,

Georgians, were on equal terms with the Polish officers and absolutely no

difference was made in anything whatsoever. ....

The

Lewandowskis lived outside of the city, in the suburb of Wilanow, where they

had a villa. Aunt Nina's maiden name was Princess Orbeliani and she was a

Georgian. Her husband was of Polish origin, but he was born and raised in Russia.

It

so happened that the Lewandowskis were close friends of my future wife's

parents and it was at their Wilanow villa that I met Missy.

One

afternoon, at the beginning of summer 1931, I decided to drive out to Wilanow.

As I can well remember it was June 29th, a holiday in Poland, St.

Peter's Day. As I arrived, my Aunt Nina introduced me to her friend, the Count

and Countess Rudiger-Bielajew. This was the very first time I saw Missy. As she

often told me in later years, the very moment she got a glimpse of me, her heart

told her that this young Georgian was going to be her husband!

Missy

was 25 years old, of slender build, and she had dark brown hair and green eyes.

Missy was a shy, reserved girl, plainly dressed in a pink cotton dress, and she

wore a wide-rimmed straw hat. She had a comfortable unsophisticated manner, so

I was feeling at ease with her the very first time we talked to each other.

Somehow Missy and I felt attracted to one another and after just a few dates,

we knew that we were in love!

Exactly

three weeks after we met, we became engaged. It was on July 22nd, one of the

happiest days of my life.

On

February 21, 1932, I asked Missy's parents for her hand. On that day, our

engagement became official and nine months later, on November 13th, we were married.

Life

is truly full of surprises: had I not decided to drive out to Wilanow that

summer afternoon, I may have never learned of the existence of my future wife,

and our lives would have turned out in a completely different way!

Fate

united us and granted us a most happy life together. We went through good and

bad years, always helping each other through the dangerous years of war. We

were supporting one another in everything and, above all, we were [mutually]

loving and respecting.

I

am deeply convinced that Missy and I are one of the happiest couples in the

entire world!

Our

wedding took place in Warsaw

in the Russian Orthodox Church on Podwale

Street. It was a big wedding and lots of guests attended:

Georgians, Russians and all our Polish friends, as well as the commander of my

regiment and all the officers. My best man was Major Dziadulski. As Missy and I

emerged from the church, the band of my regiment greeted us with the music of

the Cheveaux Legers' song!5 It was a beautiful sight: the men

dressed in their best uniforms; the brass shining in the sun! The crowd greeted

us and cheered as we were getting into our car and everybody was wishing us

luck! A very nice reception followed in the best hotel in the capital, the

Hotel Europe.

Later,

in the evening, we drove to our apartment on Agrykola Street. As we arrived, our

housekeeper greeted us with bread and salt, an old Russian tradition that is

believed to bring good luck. Missy loved the apartment... [A sentence is

missing. She said] that this was the happiest day of her life and that her

heart was so full of thanks for everything!

Our

apartment was in the Officers' building of the Cheveaux Legers Regiment on the

third floor. It had large rooms and very tall windows. The building was

surrounded by trees.

And

so, on November 13, 1932, our mutual life began and despite the fact that we

were married on the 13th, our life was the happiest one ever could dream of!

Here

is the reason why we were married on the 13th: it happened to be the last

Sunday before Advent,6 and our church does not allow weddings to be

performed during Christmas Advent. So we would have [had] to wait until

January, and my permission to marry was expiring on December 31st. After that,

I would have [had] to ask the commander of my regiment for another permission

to marry.

Missy

and I decided not to pay attention to the old superstition and go ahead with

the wedding. I must say that we never regretted this decision!

Now

I shall say a few words about my wife. She was born in St. Petersburg on April 8, 1906. Her father

was Adjutant to the Grand Duke Vladimir, brother of the Emperor Alexander III.

After the Grand Duke passed away, Count Rudiger-Bielajew became Adjutant to the

Grand Duke Andrew. On December 6, 1916, he was promoted to General. The couple

and their daughter lived through the Revolution, partially in hiding, and kept

changing apartments in order to avoid persecution. However, they did not escape

being arrested by the revolutionary government, and both Missy's parents had to

spend days in prison. Miraculously, they were not executed, nor sent to labor

camps. This happened because one of the commissars was an old acquaintance of

the Count from the time he was Adjutant, and the commissar was, at that time,

one of the palace guards.

Missy

went through a lot in her childhood. She often was very hungry and scared of

frightening things that were happening around her. One of the apartments they

were hiding in was infested by rats. She was a very independent little girl

and, at the age of twelve, she would take, alone, a trip by streetcar to visit

a sick friend in a hospital at the other end of the city.

Missy

attended a Soviet school and marched with her class in parades, memorizing

revolutionary anniversaries.

In

October 1920, the Rudiger-Bielajew family left St.

Petersburg with a secret organization that made it possible for

them to escape to Finland.

NOTES

1Father of the Chairman of the Joint

Chiefs of Staff, John M. Shalikashvili. Printed by permission of the Hoover

Institution Archives and General John M. Shalikashvili. To our knowledge, this

is the first excerpt of Dimitri Shalikashvili's Memoirs to appear in

print. Square parentheses indicate editorial additions or corrections. The

spelling of Polish names has been corrected throughout.

2 We have been unable to verify the identity of this general.

3 Jozef Pilsudski (1867- 1935) is regarded by Poles as the father of

modern Poland.

His Legion, first created under the Austrian rule, is credited with playing a

significant role in reestablishing Polish independence after World War

I.

4 Gen. Gustaw Dreszer, pseud. Orlicz (1889-1936).

5 Possibly from an operetta by Suppe, with the same title.

6 The original has "Lent," which we replaced by

"Advent" for clarity. The period before Christmas, called Advent in

many Christian denominations, is also a period of fasting.

Originally

published by The Sarmatian

Review

At http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~sarmatia/195/shalikashvili.html

|

|

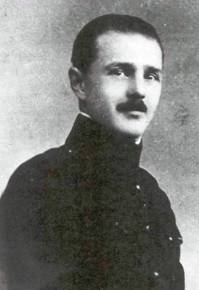

FOUGHT AND

DIED FOR POLAND

By George Nikoladze

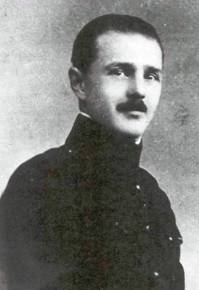

Major Giorgi Mamaladze. He went to Poland following the Soviet invasion of Georgia in

1921. Mamaladze graduated from the Polish military school and served as a

contract officer in the Polish army.

He took an active part in the 1939

September campaign against both the German and Soviet armies. Mamaladze was

then captured by the Soviets and executed along with his Georgian and Polish

comrades-in-arms during the Katyn

Massacre in 1940

|

Click here to see the

movie “The Story of Georgian Officers in Polish Army”

(in

Polish with English subtitles)