|

|

Poland: Biographical History

By Mieczyslaw Kasprzyk

Section IV

|

POST-WAR POLAND

Mikolajczyk, Stanislaw (b. 1903; d. 1966), leader of the Peasant Movement,

founder of the Stronnictwo Ludowe

(the Polish Peasant Party) and representative of the Polish Government-in-Exile

during WW2, offered the only real opposition to the Sanacja

regime established after Pilsudski’s coup. He organised

a political strike (15 August 1937) which called for a political amnesty and a

liquidation of the Sanacja. The strike turned

violent, 42 people were killed and about 1000 arrested; the events shook the

régime badly. When Sikorski was killed at Gibraltar (1943), Mikolajczyk

succeeded him as prime minister. Opposed to the Soviet annexation of East

Galicia and the imposition of the “Curzon Line” frontier on a post-war Poland,

Mikolajczyk was placed under great diplomatic

pressure and warned by Churchill, “You are on the verge of annihilation. Unless

you accept the frontier...the Russians will sweep through your country and your

people will be liquidated.” Mikolajczyk went to Moscow to discuss the situation with Stalin directly and

watched helplessly as the Soviets set up the “Polish Liberation Committee”,

under Osobka-Morawski of the PPS (Polish Socialist

Party), in Lublin

on 22 July 1944 and the subsequent disaster of the Warsaw Uprising in August.

The Uprising placed Mikolajczyk in a position where

he had to plead for help instead of strengthening his bargaining position. He

was pressurised, by the Allies, into accepting a

compromise whereby Poland

would gain land in the West as compensation for the territories lost in the

East and, despite his misgivings, he agreed that he would come to Poland to head a provisional government made up

mostly of the Lublin

committee. Mikolajczyk was concerned that the

establishment of the Polish border on the Oder-Neisse would cause problems with

any post-war German government (as had the Polish Corridor after WW1) and tie Poland to the Soviet Union

indefinitely. Any opposition became academic when the Western Powers confirmed Poland’s eastern frontier at Yalta

in February 1945 and at Potsdam

in July. At Yalta and Potsdam Stalin had agreed to set up an

interim government consisting of twenty-one members, sixteen of them sponsored

by Stalin himself; Mikolajczyk would be deputy

premier - the Allies agreed to this and withdrew their recognition of the

Polish Government-in-exile. In the January Election of 1947, in a blatant

disregard for the provisions agreed at Yalta and

Potsdam and in

elections declared to be irregular by foreign observers, the communist-led

Democratic Bloc gained power; Bierut was elected President

and Cyrankiewicz, Premier. In the Sejm,

Mikolajczyk was condemned as a foreign agent. As the

last remnants of the anti-communist underground were destroyed in the

countryside, he was forced to flee for his life from Poland (October 1947).

Mikolajczyk, Stanislaw (b. 1903; d. 1966), leader of the Peasant Movement,

founder of the Stronnictwo Ludowe

(the Polish Peasant Party) and representative of the Polish Government-in-Exile

during WW2, offered the only real opposition to the Sanacja

regime established after Pilsudski’s coup. He organised

a political strike (15 August 1937) which called for a political amnesty and a

liquidation of the Sanacja. The strike turned

violent, 42 people were killed and about 1000 arrested; the events shook the

régime badly. When Sikorski was killed at Gibraltar (1943), Mikolajczyk

succeeded him as prime minister. Opposed to the Soviet annexation of East

Galicia and the imposition of the “Curzon Line” frontier on a post-war Poland,

Mikolajczyk was placed under great diplomatic

pressure and warned by Churchill, “You are on the verge of annihilation. Unless

you accept the frontier...the Russians will sweep through your country and your

people will be liquidated.” Mikolajczyk went to Moscow to discuss the situation with Stalin directly and

watched helplessly as the Soviets set up the “Polish Liberation Committee”,

under Osobka-Morawski of the PPS (Polish Socialist

Party), in Lublin

on 22 July 1944 and the subsequent disaster of the Warsaw Uprising in August.

The Uprising placed Mikolajczyk in a position where

he had to plead for help instead of strengthening his bargaining position. He

was pressurised, by the Allies, into accepting a

compromise whereby Poland

would gain land in the West as compensation for the territories lost in the

East and, despite his misgivings, he agreed that he would come to Poland to head a provisional government made up

mostly of the Lublin

committee. Mikolajczyk was concerned that the

establishment of the Polish border on the Oder-Neisse would cause problems with

any post-war German government (as had the Polish Corridor after WW1) and tie Poland to the Soviet Union

indefinitely. Any opposition became academic when the Western Powers confirmed Poland’s eastern frontier at Yalta

in February 1945 and at Potsdam

in July. At Yalta and Potsdam Stalin had agreed to set up an

interim government consisting of twenty-one members, sixteen of them sponsored

by Stalin himself; Mikolajczyk would be deputy

premier - the Allies agreed to this and withdrew their recognition of the

Polish Government-in-exile. In the January Election of 1947, in a blatant

disregard for the provisions agreed at Yalta and

Potsdam and in

elections declared to be irregular by foreign observers, the communist-led

Democratic Bloc gained power; Bierut was elected President

and Cyrankiewicz, Premier. In the Sejm,

Mikolajczyk was condemned as a foreign agent. As the

last remnants of the anti-communist underground were destroyed in the

countryside, he was forced to flee for his life from Poland (October 1947).

The Party

Bierut,

Boleslaw (b. Rurach Jezuickich, nr. Lublin, 1892; d. Moscow, 1956),

was actively involved in the affairs of the Polish working-class from an early

age; by 1918, aged 26, he was already organising

workers in Warsaw and Lublin

and was an NKVD agent, studying at the Advanced Comintern Party

School. He became a Comintern agent in Bulgaria,

Czechoslovakia and Austria and was arrested in Poland (1935). He was a leader in

the resistance during the Nazi occupation, becoming president of the Home

National Council (KRN) formed by Wladyslaw Gomulka

without consulting Moscow.

The Soviets formed the Polski Komitet

Wyzwolenia Narodowego

(PKWN; Polish Committee of National Liberation), allegedly in July 1944 in Lublin but in reality created in Moscow to undermine Gomulka’s KRN. The role

of the Lublin Committee was to assist the Soviets in running the Polish

territories liberated from the Germans. At the Potsdam

Conference (17 July 1945) Bierut, leading the Polish

delegation, agreed to the establishment of the Oder-Neisse line as Poland’s

post-War Western border. The Lublin Committee became the core around

which was formed the Provisional Government of National Unity (1945 - 47),

ostensibly a union of Polish democratic parties with representatives from the Polska Partia Robotnicza

(PPR; Polish Workers’ Party), Polska Partia Socjilistyczna (PPS; the

Polish Socialist Party), the PSL; Polish Peasants’ Party, and other minor

parties intended to rule the country until free democratic elections could take

place. Stanislaw Mikolajczyk was the only member of

the London government to return to Poland.

In reality the Provisional Government had been set up in order to create a

breathing space during which the democratic opposition could be eliminated and

a Communist State established. In the Summer of 1947 the PSL and Mikolajczyk

became increasingly isolated and attacked as agents of reactionary forces;

during the arrests that followed Mikolajczyk managed

to escape. Bierut became Stalin’s hand-picked man to

become President of the Republic (1947 - 52) and was leader of the radical

pro-Moscow group (consisting of Jakub Berman, and

Hilary Minc) opposed to Gomulka. In June 1948 Gomulka

was replaced as General-Secretary of the Polish Workers’ Party (PPR) and on 26

July 1948 the first purges began as the PPR and PPS were cleansed of

pro-Western elements. An era of full Stalinist dictatorship and headlong industrialisation began and in December the Polish Worker’s

Party and the Polish Socialist Party fused forming the Polish United Workers’

Party (PZPR) and a single party state. In November 1949 Bierut

and the Polish government were given the services of Marshall Rokossovsky by the USSR; he was appointed Minister of Defence and given a permanent place in the Politburo. A

purge of the army was then carried out and compulsory National Service was

introduced (February 1950). The March Labour Laws

(1950) made absenteeism a crime and tied workers to their jobs, making them

responsible to their managers, and the management directly responsible for

fulfilling any quotas set by the government. On the 22 July 1952 a new

constitution was introduced and Poland

became officially known as Polska Rzeczpospolita

Ludowa (the Polish People’s Republic). In 1949 the Vatican

had issued a decree against Communism which had put all Communist publications

on the Index and forbade Catholics to cooperate with Communists, now, in 1952,

the first arrests of bishops and priests began, culminating in the arrest of

Cardinal Wyszynski (1954). In 1954, Colonel Jozef Swiatlo (b. 1905), deputy chief of the Tenth Department

(set up to monitor the activities of Party members and the government on behalf

of Moscow),

defected and began to broadcast on Radio Free Europe, revealing the activities

of the Urzad Bezpieczenstwa

(UB; Polish security services). The scandal that followed these revelations, of

the extent to which Moscow

had control over everyday life, led to the dismissal of the head of the UB and

the release of Gomulka from prison. In February 1956, with the situation

changing in a post-Stalinist world, Bierut left Poland to attend the Twentieth Congress of the

Soviet Communist Party in Moscow

during which Khrushchev denounced Stalin. He died there, apparently by suicide.

His replacement was Edward Ochab

Bierut,

Boleslaw (b. Rurach Jezuickich, nr. Lublin, 1892; d. Moscow, 1956),

was actively involved in the affairs of the Polish working-class from an early

age; by 1918, aged 26, he was already organising

workers in Warsaw and Lublin

and was an NKVD agent, studying at the Advanced Comintern Party

School. He became a Comintern agent in Bulgaria,

Czechoslovakia and Austria and was arrested in Poland (1935). He was a leader in

the resistance during the Nazi occupation, becoming president of the Home

National Council (KRN) formed by Wladyslaw Gomulka

without consulting Moscow.

The Soviets formed the Polski Komitet

Wyzwolenia Narodowego

(PKWN; Polish Committee of National Liberation), allegedly in July 1944 in Lublin but in reality created in Moscow to undermine Gomulka’s KRN. The role

of the Lublin Committee was to assist the Soviets in running the Polish

territories liberated from the Germans. At the Potsdam

Conference (17 July 1945) Bierut, leading the Polish

delegation, agreed to the establishment of the Oder-Neisse line as Poland’s

post-War Western border. The Lublin Committee became the core around

which was formed the Provisional Government of National Unity (1945 - 47),

ostensibly a union of Polish democratic parties with representatives from the Polska Partia Robotnicza

(PPR; Polish Workers’ Party), Polska Partia Socjilistyczna (PPS; the

Polish Socialist Party), the PSL; Polish Peasants’ Party, and other minor

parties intended to rule the country until free democratic elections could take

place. Stanislaw Mikolajczyk was the only member of

the London government to return to Poland.

In reality the Provisional Government had been set up in order to create a

breathing space during which the democratic opposition could be eliminated and

a Communist State established. In the Summer of 1947 the PSL and Mikolajczyk

became increasingly isolated and attacked as agents of reactionary forces;

during the arrests that followed Mikolajczyk managed

to escape. Bierut became Stalin’s hand-picked man to

become President of the Republic (1947 - 52) and was leader of the radical

pro-Moscow group (consisting of Jakub Berman, and

Hilary Minc) opposed to Gomulka. In June 1948 Gomulka

was replaced as General-Secretary of the Polish Workers’ Party (PPR) and on 26

July 1948 the first purges began as the PPR and PPS were cleansed of

pro-Western elements. An era of full Stalinist dictatorship and headlong industrialisation began and in December the Polish Worker’s

Party and the Polish Socialist Party fused forming the Polish United Workers’

Party (PZPR) and a single party state. In November 1949 Bierut

and the Polish government were given the services of Marshall Rokossovsky by the USSR; he was appointed Minister of Defence and given a permanent place in the Politburo. A

purge of the army was then carried out and compulsory National Service was

introduced (February 1950). The March Labour Laws

(1950) made absenteeism a crime and tied workers to their jobs, making them

responsible to their managers, and the management directly responsible for

fulfilling any quotas set by the government. On the 22 July 1952 a new

constitution was introduced and Poland

became officially known as Polska Rzeczpospolita

Ludowa (the Polish People’s Republic). In 1949 the Vatican

had issued a decree against Communism which had put all Communist publications

on the Index and forbade Catholics to cooperate with Communists, now, in 1952,

the first arrests of bishops and priests began, culminating in the arrest of

Cardinal Wyszynski (1954). In 1954, Colonel Jozef Swiatlo (b. 1905), deputy chief of the Tenth Department

(set up to monitor the activities of Party members and the government on behalf

of Moscow),

defected and began to broadcast on Radio Free Europe, revealing the activities

of the Urzad Bezpieczenstwa

(UB; Polish security services). The scandal that followed these revelations, of

the extent to which Moscow

had control over everyday life, led to the dismissal of the head of the UB and

the release of Gomulka from prison. In February 1956, with the situation

changing in a post-Stalinist world, Bierut left Poland to attend the Twentieth Congress of the

Soviet Communist Party in Moscow

during which Khrushchev denounced Stalin. He died there, apparently by suicide.

His replacement was Edward Ochab

Gomulka,

Wladyslaw (b. Krosno, 1905; d. Warsaw, 1982). Trained in

the USSR in the 1930s, where

he saw collectivisation at first hand (and decided

that it would not work in Poland),

Gomulka was fortunate enough to be arrested by the Polish police (1938 - 39)

and thus avoided the purge of his comrades (some 5,000 were killed) by the

Soviets. He found himself in Soviet-occupied Lwow in

1940 and decided to take his chances at home, Krosno,

in the General-Gouvernement. In Warsaw, Gomulka emerged as the First

Secretary of the Polish Workers’ Party (PPR) (1943). He formed the People’s

Army as an equivalent to the Armia Krajowa, and the Krajowa Rada Narodowa (KRN; National

People’s Council) - without Moscow’s

prior permission - in 1944. As a result, the Soviets formed the Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego (PKWN;

Polish Committee of National Liberation), allegedly in July 1944 in Lublin but in reality created in Moscow to undermine Gomulka’s KRN. Gomulka

was “invited” to Moscow

to endorse the formation of the Polish Committee of National Liberation, which

he did in August (although all documentation was back-dated to July). The role

of the Lublin Committee was to assist the Soviets in running the Polish

territories liberated from the Germans. The Lublin Committee then became the

core around which was formed the Provisional Government of National Unity (1945

- 47), ostensibly a union of Polish democratic parties intended to rule the

country until free democratic elections could take place but in reality set up in

order to create a breathing space during which the democratic opposition could

be eliminated and a Communist State established. Civil War broke out as

non-Communist elements (the right-wing, anti-communist partisans of the Holy

Cross Mountains, NZA; the National Armed Forces: former members of the AK

opposed to a Communist take-over, WiN; the

Association of Freedom and Independence, working mainly around Lublin and

Bialystok: and UPA; the Ukrainian Insurrectionary Army) opposed the hard-handed

tactics of the Soviet security forces, but all armed opposition was put down by

1947. The Polish Communists had to work in close partnership with the Soviets;

neither could succeed in Poland

without the support of the other and Gomulka played a very clever game in the

middle ground between blind allegiance to Moscow

and open rebellion. He found himself surrounded by NKVD appointments (Bierut, Berman and Minc) and

slowly being eased out of office as Stalinism was imposed on Poland (1948 - 56). He was placed

under house arrest for “nationalist deviation” and was replaced as Party

General-Secretary by Bierut. He managed to stay on as

Vice-President until 1949, and as a member of the

Central Committee until 1951 when he was imprisoned (but there were never any

show trials and executions as there had been in Hungary

and Czechoslovakia).

When Stalinism collapsed many prominent Stalinists were dismissed and there was

a call for greater civil and political freedom; the Thaw. In June 1956 workers

from the largest factory in Poland,

the Cegielski locomotive factory (or ZISPO) in Poznan, angry at unfavourable changes in taxation, made demands for talks

with the Prime Minister, Cyrankiewicz. When this was

denied there was a series of escalating strikes and a

protest march (28 June 1956) which was fired on when the authorities panicked.

During the two days of violent protest that ensued, the Poznan riots (28 - 29 June), 53 were killed

and 300 injured. Whilst the Soviets saw the riots as part of an imperialist

plot to destroy Communism at a time of internal reconstruction (Khrushchev's

de-Stalinization program in the USSR),

the Polish government took a more realistic stance and declared that the

rioting workers had been at least partly justified in their actions. The

Soviets became further alarmed when, in September, the Politburo had begun to

request the pull-out of all Soviet state security (KGB) advisers from Poland

and because Gomulka, who had been released along with his colleagues, was on

the verge of reclaiming his position as the PZPR (Polish United Workers’ Party)

leader. The Soviets feared that if Gomulka took control he would remove the

most orthodox (and pro-Soviet) members of the Polish leadership and steer Poland

along an independent course in foreign policy. On 19 October, as the 8th Plenum

of the PZPR Central Committee was about to convene to elect Gomulka as party

leader, Soviet forces stationed in Western Russia began to move towards Poland

and others stationed near the German border began to move towards Warsaw. Marshal

Rokossowski, the Deputy Prime Minister and the

embodiment of the Soviet presence in Poland, ordered the Polish army to

co-ordinate movements with these Soviet forces. Khrushchev now attempted to

force the Polish government to reimpose strict

ideological controls but was finally forced to agree to a compromise when loyal

Polish troops took up strategic positions around Warsaw and it was suspected that weapons were

being distributed to workers militia units. Khrushchev was reluctant to

instigate a military solution that would be difficult to end. Gomulka was

permitted to return to power and take Poland along its own road to Socialism

whilst, in return, Gomulka called for stronger political and military ties with

the Soviet Union and condemned those who were trying to steer Poland away from

the Warsaw Pact. Rokossowski’s behaviour

during the crisis was now brought into question and when a new Politburo was

set up he was not re-elected onto it. Shortly afterwards he was expelled by

Gomulka (28 October 1956) on charges of attempting to stage a pro-Soviet coup.

The deteriorating situation in Hungary

was a strong incentive for Khrushchev to avoid further conflict with Poland.

Unlike the unhappy outcome of the Hungarian Revolution a few weeks later, this

Polish “revolution” was a relative success: Cardinal Wyszynski, imprisoned by Bierut, was released; Russian officers in the Polish army

were dismissed and sent home; a quarter of a million Poles stranded in the

Soviet Union were allowed to emigrate to Poland; commercial treaties were

renegotiated on more favourable terms; and the Soviet

Union had to pay for the upkeep of its own troops in Poland. Whilst Soviet

puppets had been withdrawn from Poland there was still a powerful Stalinist

group, known as the “Natolinists” (named after the Branicki palace where they met), within Poland who now

attempted to divert any attention away from them by encouraging anti-Semitism;

to blame the number of Jews who had prospered under Stalinism. There was also a

concerted attempt to purge Piasecki and his

ex-Fascist group. Gomulka’s drive for self-sufficiency throughout the 60s,

especially in agriculture, failed to produce a promised rise in living

standards. Party bureaucracy increased and, after the fall of Khrushchev in

1964, censorship was strengthened. The Israeli victory over the Soviet–backed

Arabs in 1967 was greeted with glee; “Our Jews have given the Soviet Arabs a

drumming!” Anti–Russian feelings grew, especially in the universities, until,

when the authorities banned a production of Mickiewicz’s anti–Russian

“Forefathers’ Eve” in January, student riots broke out in Warsaw

and Krakow. These were forcibly put down and a

period of repression against Intellectuals and Jews ensued. Gomulka found his

own position as leader was under threat from the repressive Nationalist

“Partisan” faction, led by Mieczyslaw Moczar, but he was able to get Soviet backing by letting

Polish armed forces take part in the Warsaw Pact repression of Dubcek’s attempt

to create a more liberal situation in Czechoslovakia. Terrified of

incurring debts, Gomulka resisted imports, especially of grain and animal feed,

thus two bad harvests (1969 and 1970) inevitably led to severe meat shortages.

A sudden increase in the price of food in December 1970 led to riots in the

Baltic cities; Gdansk, Gdynia

and Szczecin,

which were repressed with great bloodshed. The fighting spread to other cities

on the coast and the whole area had to be sealed off by the army. On 19

December an emergency meeting of the Politburo replaced Gomulka (who had

suffered a stroke) with Edward Gierek, who managed to

calm down the situation by preventing the price rises and promising reforms.

Gomulka died of cancer (1982).

Gomulka,

Wladyslaw (b. Krosno, 1905; d. Warsaw, 1982). Trained in

the USSR in the 1930s, where

he saw collectivisation at first hand (and decided

that it would not work in Poland),

Gomulka was fortunate enough to be arrested by the Polish police (1938 - 39)

and thus avoided the purge of his comrades (some 5,000 were killed) by the

Soviets. He found himself in Soviet-occupied Lwow in

1940 and decided to take his chances at home, Krosno,

in the General-Gouvernement. In Warsaw, Gomulka emerged as the First

Secretary of the Polish Workers’ Party (PPR) (1943). He formed the People’s

Army as an equivalent to the Armia Krajowa, and the Krajowa Rada Narodowa (KRN; National

People’s Council) - without Moscow’s

prior permission - in 1944. As a result, the Soviets formed the Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego (PKWN;

Polish Committee of National Liberation), allegedly in July 1944 in Lublin but in reality created in Moscow to undermine Gomulka’s KRN. Gomulka

was “invited” to Moscow

to endorse the formation of the Polish Committee of National Liberation, which

he did in August (although all documentation was back-dated to July). The role

of the Lublin Committee was to assist the Soviets in running the Polish

territories liberated from the Germans. The Lublin Committee then became the

core around which was formed the Provisional Government of National Unity (1945

- 47), ostensibly a union of Polish democratic parties intended to rule the

country until free democratic elections could take place but in reality set up in

order to create a breathing space during which the democratic opposition could

be eliminated and a Communist State established. Civil War broke out as

non-Communist elements (the right-wing, anti-communist partisans of the Holy

Cross Mountains, NZA; the National Armed Forces: former members of the AK

opposed to a Communist take-over, WiN; the

Association of Freedom and Independence, working mainly around Lublin and

Bialystok: and UPA; the Ukrainian Insurrectionary Army) opposed the hard-handed

tactics of the Soviet security forces, but all armed opposition was put down by

1947. The Polish Communists had to work in close partnership with the Soviets;

neither could succeed in Poland

without the support of the other and Gomulka played a very clever game in the

middle ground between blind allegiance to Moscow

and open rebellion. He found himself surrounded by NKVD appointments (Bierut, Berman and Minc) and

slowly being eased out of office as Stalinism was imposed on Poland (1948 - 56). He was placed

under house arrest for “nationalist deviation” and was replaced as Party

General-Secretary by Bierut. He managed to stay on as

Vice-President until 1949, and as a member of the

Central Committee until 1951 when he was imprisoned (but there were never any

show trials and executions as there had been in Hungary

and Czechoslovakia).

When Stalinism collapsed many prominent Stalinists were dismissed and there was

a call for greater civil and political freedom; the Thaw. In June 1956 workers

from the largest factory in Poland,

the Cegielski locomotive factory (or ZISPO) in Poznan, angry at unfavourable changes in taxation, made demands for talks

with the Prime Minister, Cyrankiewicz. When this was

denied there was a series of escalating strikes and a

protest march (28 June 1956) which was fired on when the authorities panicked.

During the two days of violent protest that ensued, the Poznan riots (28 - 29 June), 53 were killed

and 300 injured. Whilst the Soviets saw the riots as part of an imperialist

plot to destroy Communism at a time of internal reconstruction (Khrushchev's

de-Stalinization program in the USSR),

the Polish government took a more realistic stance and declared that the

rioting workers had been at least partly justified in their actions. The

Soviets became further alarmed when, in September, the Politburo had begun to

request the pull-out of all Soviet state security (KGB) advisers from Poland

and because Gomulka, who had been released along with his colleagues, was on

the verge of reclaiming his position as the PZPR (Polish United Workers’ Party)

leader. The Soviets feared that if Gomulka took control he would remove the

most orthodox (and pro-Soviet) members of the Polish leadership and steer Poland

along an independent course in foreign policy. On 19 October, as the 8th Plenum

of the PZPR Central Committee was about to convene to elect Gomulka as party

leader, Soviet forces stationed in Western Russia began to move towards Poland

and others stationed near the German border began to move towards Warsaw. Marshal

Rokossowski, the Deputy Prime Minister and the

embodiment of the Soviet presence in Poland, ordered the Polish army to

co-ordinate movements with these Soviet forces. Khrushchev now attempted to

force the Polish government to reimpose strict

ideological controls but was finally forced to agree to a compromise when loyal

Polish troops took up strategic positions around Warsaw and it was suspected that weapons were

being distributed to workers militia units. Khrushchev was reluctant to

instigate a military solution that would be difficult to end. Gomulka was

permitted to return to power and take Poland along its own road to Socialism

whilst, in return, Gomulka called for stronger political and military ties with

the Soviet Union and condemned those who were trying to steer Poland away from

the Warsaw Pact. Rokossowski’s behaviour

during the crisis was now brought into question and when a new Politburo was

set up he was not re-elected onto it. Shortly afterwards he was expelled by

Gomulka (28 October 1956) on charges of attempting to stage a pro-Soviet coup.

The deteriorating situation in Hungary

was a strong incentive for Khrushchev to avoid further conflict with Poland.

Unlike the unhappy outcome of the Hungarian Revolution a few weeks later, this

Polish “revolution” was a relative success: Cardinal Wyszynski, imprisoned by Bierut, was released; Russian officers in the Polish army

were dismissed and sent home; a quarter of a million Poles stranded in the

Soviet Union were allowed to emigrate to Poland; commercial treaties were

renegotiated on more favourable terms; and the Soviet

Union had to pay for the upkeep of its own troops in Poland. Whilst Soviet

puppets had been withdrawn from Poland there was still a powerful Stalinist

group, known as the “Natolinists” (named after the Branicki palace where they met), within Poland who now

attempted to divert any attention away from them by encouraging anti-Semitism;

to blame the number of Jews who had prospered under Stalinism. There was also a

concerted attempt to purge Piasecki and his

ex-Fascist group. Gomulka’s drive for self-sufficiency throughout the 60s,

especially in agriculture, failed to produce a promised rise in living

standards. Party bureaucracy increased and, after the fall of Khrushchev in

1964, censorship was strengthened. The Israeli victory over the Soviet–backed

Arabs in 1967 was greeted with glee; “Our Jews have given the Soviet Arabs a

drumming!” Anti–Russian feelings grew, especially in the universities, until,

when the authorities banned a production of Mickiewicz’s anti–Russian

“Forefathers’ Eve” in January, student riots broke out in Warsaw

and Krakow. These were forcibly put down and a

period of repression against Intellectuals and Jews ensued. Gomulka found his

own position as leader was under threat from the repressive Nationalist

“Partisan” faction, led by Mieczyslaw Moczar, but he was able to get Soviet backing by letting

Polish armed forces take part in the Warsaw Pact repression of Dubcek’s attempt

to create a more liberal situation in Czechoslovakia. Terrified of

incurring debts, Gomulka resisted imports, especially of grain and animal feed,

thus two bad harvests (1969 and 1970) inevitably led to severe meat shortages.

A sudden increase in the price of food in December 1970 led to riots in the

Baltic cities; Gdansk, Gdynia

and Szczecin,

which were repressed with great bloodshed. The fighting spread to other cities

on the coast and the whole area had to be sealed off by the army. On 19

December an emergency meeting of the Politburo replaced Gomulka (who had

suffered a stroke) with Edward Gierek, who managed to

calm down the situation by preventing the price rises and promising reforms.

Gomulka died of cancer (1982).

Gierek,

Edward (b. 1913; d.

Cieszyn, 2001), First Secretary of the Polish

Communist Party during the rise of Solidarity, went to France with his family in his youth

and lived there for eleven years. At the age of 13 he began work as a miner and

spent a great deal of his time in the ultra-Stalinist communist parties of France and Belgium. He was expelled from France for his political activities and went to Poland (1934), returning to Belgium in 1937. He was in the

resistance during the war. Gierek returned to Poland

in 1948 where he quickly role to positions of power. He became the first Party

leader in the Soviet bloc who had never been trained in the Soviet

Union. Gierek built up his reputation as

a very able administrator and Party boss in Silesia, whilst maintaining some distance

from other factions and intrigues in the Party. He was able to maintain in

touch with the common people and understood that a gulf existed between the

standard of living of working people in Poland and their counterparts in

the West. He was appointed Director of the Heavy Industry Department (1954) and

elevated to the Politburo (1956). After the crisis of December 1970, when food

prices rose steeply during Christmas week and there were strikes and

demonstrations against the Government - most notably in the shipyards of Gdansk, Gdynia and Szczecin, Gomulka was

forced to resign and Gierek was elevated in his

place. His policy was one of freezing prices, rapid industrialisation,

and of creating an artificial rise in living standards thus attempting to

create a sense of material prosperity based on Western imports and credits (a

policy which was to bankrupt Poland).

For a brief period, 1971 - 73, there was a sense of confidence and optimism;

free discussion was encouraged, wages increased, the prices paid by the

Government to peasants for food was raised, intellectuals were wooed and

censorship eased. The Royal Castle in Warsaw

was rebuilt. Gierek staked all on economic success

and failed after a series of world and domestic crises (the oil crisis of 1974,

deepening world recession). To ease the foreign debt Gierek

was forced to increase the price of “luxury” consumer goods, and, in June 1976,

food prices by an average of 60%. There were major demonstrations and violent strikes;

the workers of the Ursus plant tore up railway tracks

and seized the Paris - Moscow express, whilst the army had to man

the deserted steelworks of Nowa Huta.

Within days the action forced the cancellation of the price rises, but also -

since coercion was the only way left - led to repression by the Citizens’

Militia (ZOMO) and severe sentences. Opposition groups developed and grew in

strength; KOR (the Worker’s Defence Committee), led

by Jacek Kuron and Adam Michnik. The economy “overheated” and led to a period of

acute consumer shortages, especially meat, and a soaring foreign debt. In

October 1978, Karol Wojtyla, Cardinal of Krakow, was

elected Pope. The Polish sense of “destiny” began to surface. In June, 1979,

Pope John Paul II visited Poland

at a time when the economic crisis was deepening. Fresh price rises in July

1980 touched off nation–wide strikes. In August they reached the Lenin

Shipyard, Gdansk,

where Lech Walesa became leader. At the end of August the Gdansk Agreement

created Solidarity as an independent, self–managing trade union. Gierek was replaced by Stanislaw Kania

in September and expelled from the party for having failed to improve the

living standards of the workers. In the period that followed the Party began to

fall apart and on 13 December 1981 General Jaruzelski,

prime minister, minister of defence and first

secretary of PZPR, declared a state of martial law and suspended Solidarity -

but nothing would ever be the same again.

Gierek,

Edward (b. 1913; d.

Cieszyn, 2001), First Secretary of the Polish

Communist Party during the rise of Solidarity, went to France with his family in his youth

and lived there for eleven years. At the age of 13 he began work as a miner and

spent a great deal of his time in the ultra-Stalinist communist parties of France and Belgium. He was expelled from France for his political activities and went to Poland (1934), returning to Belgium in 1937. He was in the

resistance during the war. Gierek returned to Poland

in 1948 where he quickly role to positions of power. He became the first Party

leader in the Soviet bloc who had never been trained in the Soviet

Union. Gierek built up his reputation as

a very able administrator and Party boss in Silesia, whilst maintaining some distance

from other factions and intrigues in the Party. He was able to maintain in

touch with the common people and understood that a gulf existed between the

standard of living of working people in Poland and their counterparts in

the West. He was appointed Director of the Heavy Industry Department (1954) and

elevated to the Politburo (1956). After the crisis of December 1970, when food

prices rose steeply during Christmas week and there were strikes and

demonstrations against the Government - most notably in the shipyards of Gdansk, Gdynia and Szczecin, Gomulka was

forced to resign and Gierek was elevated in his

place. His policy was one of freezing prices, rapid industrialisation,

and of creating an artificial rise in living standards thus attempting to

create a sense of material prosperity based on Western imports and credits (a

policy which was to bankrupt Poland).

For a brief period, 1971 - 73, there was a sense of confidence and optimism;

free discussion was encouraged, wages increased, the prices paid by the

Government to peasants for food was raised, intellectuals were wooed and

censorship eased. The Royal Castle in Warsaw

was rebuilt. Gierek staked all on economic success

and failed after a series of world and domestic crises (the oil crisis of 1974,

deepening world recession). To ease the foreign debt Gierek

was forced to increase the price of “luxury” consumer goods, and, in June 1976,

food prices by an average of 60%. There were major demonstrations and violent strikes;

the workers of the Ursus plant tore up railway tracks

and seized the Paris - Moscow express, whilst the army had to man

the deserted steelworks of Nowa Huta.

Within days the action forced the cancellation of the price rises, but also -

since coercion was the only way left - led to repression by the Citizens’

Militia (ZOMO) and severe sentences. Opposition groups developed and grew in

strength; KOR (the Worker’s Defence Committee), led

by Jacek Kuron and Adam Michnik. The economy “overheated” and led to a period of

acute consumer shortages, especially meat, and a soaring foreign debt. In

October 1978, Karol Wojtyla, Cardinal of Krakow, was

elected Pope. The Polish sense of “destiny” began to surface. In June, 1979,

Pope John Paul II visited Poland

at a time when the economic crisis was deepening. Fresh price rises in July

1980 touched off nation–wide strikes. In August they reached the Lenin

Shipyard, Gdansk,

where Lech Walesa became leader. At the end of August the Gdansk Agreement

created Solidarity as an independent, self–managing trade union. Gierek was replaced by Stanislaw Kania

in September and expelled from the party for having failed to improve the

living standards of the workers. In the period that followed the Party began to

fall apart and on 13 December 1981 General Jaruzelski,

prime minister, minister of defence and first

secretary of PZPR, declared a state of martial law and suspended Solidarity -

but nothing would ever be the same again.

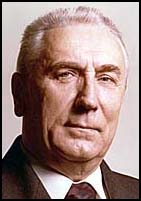

Jaruzelski,

Wojciech (b. Kurow, 1923). Born into a

wealthy land-owning family, Jaruzelski was deported

to the Soviet Union in 1939 and worked as a

forced labourer. In 1943 he joined Berling’s Kosciuszko Infantry

Division and was involved in the Eastern Campaign. He became the youngest

general in the Polish Army when he was 33. In 1962 he was appointed Deputy Defence Minister and promoted to Defence

Minister in 1968. In the circumstances that led to the the

Gdansk Agreement and the creation of Solidarity in what was the first,

authentic workers’ revolution in Europe, ironically directed against the party

of the proletariat, not many had foreseen the economic and political collapse

that followed. The Party began to fall apart as its leadership became embroiled

in in-fighting and there were struggles within Solidarity itself between those

who wished to consolidate their position and those who wanted to go further.

When at Solidarity’s First National Congress (September 1981) more radical

elements were able to get a motion passed offering sympathy and support to the

downtrodden peoples of the Soviet Bloc, it was inevitable that something would

be done. The Soviet Union was isolated because of its involvement in the war in

Afghanistan,

and economically dependent on the West, but it could not stand by and watch the

very core of the Warsaw Pact tear itself away. On 9th February 1981, General Jaruzelski (commander-in-chief of the army) had been

appointed prime minister and minister of defence in

what may have been a first step towards a military coup or a pre-emptive strike

to forestall Soviet invasion - or simply a response to Soviet demands - and on

18 October he replaced Stanislaw Kania as first

secretary of PZPR, acquiring powers that were unprecedented in the Soviet Bloc.

On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski declared a “State of War”, and martial law

was imposed. In a complex and efficient operation, communications were cut and

thousands were imprisoned as tanks patrolled the streets. Whilst there were

some minor protests there was no general movement of revolt; by January 1982

the whole situation was under control. Some members of Solidarity were in

hiding and carried on in opposition underground. Solidarity was dissolved by

the courts (October 1982) and a year after its imposition, the “State of War” was suspended

(December 1982). Gradually, as the country’s political and economic life

returned to normal, martial law was lifted (July 1983). On 19 October 1984 Jerzy Popieluszko, a Warsaw priest, was

murdered by officers from the security services; Jaruzelski

sanctioned their arrest and trial. By the summer of 1985, Jaruzelski

began to appear in civilian clothes and shortly afterwards was elected

president. From 1986 onwards, there was great discussion as to the way the

country could develop (in the climate of Gorbachev’s “glasnost” and

“perestroika”) which led, in 1988, to a referendum. As a result, Poland

became the first Eastern-Bloc country to hold free elections which opened the

way to the massive changes of 1989 and the return of democracy. Whilst Jaruzelski was narrowly appointed President by the Sejm in June 1989, Tadeusz

Mazowiecki, Walesa’s Solidarity colleague, became the first non-Communist Prime

Minister since WW2. Jaruzelski relinquished his post

in July 1990 and, in December 1990, Lech Walesa was sworn in as the first

non–Communist Polish President since WW2. The role of General Jaruzelski in bringing about a free Poland will be debated

for a long time until we know the historical facts; was he simply obeying his

Moscow taskmasters or was he playing a subtle political game in order to

preserve Poland’s independence?

Jaruzelski,

Wojciech (b. Kurow, 1923). Born into a

wealthy land-owning family, Jaruzelski was deported

to the Soviet Union in 1939 and worked as a

forced labourer. In 1943 he joined Berling’s Kosciuszko Infantry

Division and was involved in the Eastern Campaign. He became the youngest

general in the Polish Army when he was 33. In 1962 he was appointed Deputy Defence Minister and promoted to Defence

Minister in 1968. In the circumstances that led to the the

Gdansk Agreement and the creation of Solidarity in what was the first,

authentic workers’ revolution in Europe, ironically directed against the party

of the proletariat, not many had foreseen the economic and political collapse

that followed. The Party began to fall apart as its leadership became embroiled

in in-fighting and there were struggles within Solidarity itself between those

who wished to consolidate their position and those who wanted to go further.

When at Solidarity’s First National Congress (September 1981) more radical

elements were able to get a motion passed offering sympathy and support to the

downtrodden peoples of the Soviet Bloc, it was inevitable that something would

be done. The Soviet Union was isolated because of its involvement in the war in

Afghanistan,

and economically dependent on the West, but it could not stand by and watch the

very core of the Warsaw Pact tear itself away. On 9th February 1981, General Jaruzelski (commander-in-chief of the army) had been

appointed prime minister and minister of defence in

what may have been a first step towards a military coup or a pre-emptive strike

to forestall Soviet invasion - or simply a response to Soviet demands - and on

18 October he replaced Stanislaw Kania as first

secretary of PZPR, acquiring powers that were unprecedented in the Soviet Bloc.

On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski declared a “State of War”, and martial law

was imposed. In a complex and efficient operation, communications were cut and

thousands were imprisoned as tanks patrolled the streets. Whilst there were

some minor protests there was no general movement of revolt; by January 1982

the whole situation was under control. Some members of Solidarity were in

hiding and carried on in opposition underground. Solidarity was dissolved by

the courts (October 1982) and a year after its imposition, the “State of War” was suspended

(December 1982). Gradually, as the country’s political and economic life

returned to normal, martial law was lifted (July 1983). On 19 October 1984 Jerzy Popieluszko, a Warsaw priest, was

murdered by officers from the security services; Jaruzelski

sanctioned their arrest and trial. By the summer of 1985, Jaruzelski

began to appear in civilian clothes and shortly afterwards was elected

president. From 1986 onwards, there was great discussion as to the way the

country could develop (in the climate of Gorbachev’s “glasnost” and

“perestroika”) which led, in 1988, to a referendum. As a result, Poland

became the first Eastern-Bloc country to hold free elections which opened the

way to the massive changes of 1989 and the return of democracy. Whilst Jaruzelski was narrowly appointed President by the Sejm in June 1989, Tadeusz

Mazowiecki, Walesa’s Solidarity colleague, became the first non-Communist Prime

Minister since WW2. Jaruzelski relinquished his post

in July 1990 and, in December 1990, Lech Walesa was sworn in as the first

non–Communist Polish President since WW2. The role of General Jaruzelski in bringing about a free Poland will be debated

for a long time until we know the historical facts; was he simply obeying his

Moscow taskmasters or was he playing a subtle political game in order to

preserve Poland’s independence?

“...for the Soviets, to rule Poland

was the key to the control of Eastern Europe. Poland's geostrategical

importance... exceeds the fact that it lies on the way to Germany. Moscow

needed to exert her rule over Poland

because that also made it easier to control Czechoslovakia

and Hungary and isolated

non-Russian minorities in the Soviet Union from

western influence... I was fully aware of the situation. I was subject to a

continuous wave of... threats in which not only the Soviet voice was audible...

Warsaw Pact army concentrations and movements around our borders had been going

on for a considerable time... A no less threatening situation was caused by

what was, in effect, an ultimatum announcing a drastic cut in the supplies of

gas, crude oil and many other vitally important materials as of the 1st January

1982... No grand issues and dilemmas may be studied without their historical

backgrounds in separation from the realities of a given moment. A historian

seated in the tranquillity of archives and libraries

can allow his thoughts to wander in various directions... he knows today what

took place in the past. But a politician active at that time knew only what was

happening at a given moment. And he also had to take into account that which

could take place... A politician has to bear the weight of decisions whose

effects are often enormous. And those decisions have to be taken. A

controversial decision is better than no decision or waiving it, since it

permits a situation to be brought under control while allowing it to be reined

in with the possibility of correction.“

Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski,

105th Landon Lecture, Kansas

State University,

11 March 1996

A New Hope

Wojtyla, Karol (Pope John Paul II) (b. Wadowice,1920),

the 264th Pontiff, is the first non-Italian Pontiff for 455 years, the first

from a Communist country and the first Polish Pope. His mother died when he was

small and he was brought up by his rather stern father. In 1938 Wojtyla entered the Jagiellonian University,

Krakow, studying languages and modern Polish

literature. He began to write poetry and joined a theatre group intending to

follow a career in acting. With the Nazi occupation Wojtyla

became an underground cultural resistance worker combating the German attempts

to destroy Polish culture. He also began to attend underground classes in

theology and began studying for the priesthood, under Cardinal Sapieha, in 1944 whilst in hiding in the Archbishop’s

residence in Krakow. Wojtyla

was ordained on 1 November 1946, and carried on his studies in Rome

and France.

On returning in 1948 he was appointed parish priest in Niegowic,

near Gdow. Wojtyla was

transferred to the Kosciol Floriana

(the Collegiate Church of St.Florian) in the Kleparz district of Krakow, which has been the University

Collegiate since the 16th.century. He was vicar here between

1949-51. In 1954 he became a professor of social ethics at the Catholic

University of Lublin and in 1958 was made a Bishop by Cardinal Wyszynski. In

1964 Wojtyla became Archbishop of Krakow

and in 1967, a Cardinal. During the 60s he had to continually fight the

Communist authorities for the right to build new churches and to maintain

religious education. Cardinal Wojtyla played a

prominent role in the work of the Second Vatican Council and made many strong

contacts abroad. He was elected Pope on 16 October 1978 and the political

revolution that shook Poland,

and then the rest of Eastern Europe, dates

from that time. The election of a Polish Pope was a source of great pride not

only for the Poles but for all Slavs; when the Soviet leader and architect of

Perestroika, Mikhail Gorbachev, and his wife Raisa

visited the Pope in December 1989 he introduced John Paul II to her with the

words "I should like to introduce His Holiness, who is the highest moral

authority on earth, but he's also a Slav." He is the most widely-travelled Pope in history and he has taken his duties as

Bishop of Rome much more conscientiously than many of his predecessors,

visiting most of his parishes and playing an active role in his diocese. John

Paul II’s health suffered badly after an

assassination attempt (13 May 1981) and in his later years he had Parkinson’s

disease. There have been many criticisms of his Papacy; that he was

hypocritical in his condemnation of the Latin American Churches in their

struggle against Capitalism (given his story of struggle in Poland) and of

being a conservative hampering the Church in a time of great liberalisation and change - especially in the US. History

will judge him but there can be no denial of the fact that he played an

important role in creating moral stability, especially in his constant fight

for the right of life, in times of flux and spiritual uncertainty.

Wojtyla, Karol (Pope John Paul II) (b. Wadowice,1920),

the 264th Pontiff, is the first non-Italian Pontiff for 455 years, the first

from a Communist country and the first Polish Pope. His mother died when he was

small and he was brought up by his rather stern father. In 1938 Wojtyla entered the Jagiellonian University,

Krakow, studying languages and modern Polish

literature. He began to write poetry and joined a theatre group intending to

follow a career in acting. With the Nazi occupation Wojtyla

became an underground cultural resistance worker combating the German attempts

to destroy Polish culture. He also began to attend underground classes in

theology and began studying for the priesthood, under Cardinal Sapieha, in 1944 whilst in hiding in the Archbishop’s

residence in Krakow. Wojtyla

was ordained on 1 November 1946, and carried on his studies in Rome

and France.

On returning in 1948 he was appointed parish priest in Niegowic,

near Gdow. Wojtyla was

transferred to the Kosciol Floriana

(the Collegiate Church of St.Florian) in the Kleparz district of Krakow, which has been the University

Collegiate since the 16th.century. He was vicar here between

1949-51. In 1954 he became a professor of social ethics at the Catholic

University of Lublin and in 1958 was made a Bishop by Cardinal Wyszynski. In

1964 Wojtyla became Archbishop of Krakow

and in 1967, a Cardinal. During the 60s he had to continually fight the

Communist authorities for the right to build new churches and to maintain

religious education. Cardinal Wojtyla played a

prominent role in the work of the Second Vatican Council and made many strong

contacts abroad. He was elected Pope on 16 October 1978 and the political

revolution that shook Poland,

and then the rest of Eastern Europe, dates

from that time. The election of a Polish Pope was a source of great pride not

only for the Poles but for all Slavs; when the Soviet leader and architect of

Perestroika, Mikhail Gorbachev, and his wife Raisa

visited the Pope in December 1989 he introduced John Paul II to her with the

words "I should like to introduce His Holiness, who is the highest moral

authority on earth, but he's also a Slav." He is the most widely-travelled Pope in history and he has taken his duties as

Bishop of Rome much more conscientiously than many of his predecessors,

visiting most of his parishes and playing an active role in his diocese. John

Paul II’s health suffered badly after an

assassination attempt (13 May 1981) and in his later years he had Parkinson’s

disease. There have been many criticisms of his Papacy; that he was

hypocritical in his condemnation of the Latin American Churches in their

struggle against Capitalism (given his story of struggle in Poland) and of

being a conservative hampering the Church in a time of great liberalisation and change - especially in the US. History

will judge him but there can be no denial of the fact that he played an

important role in creating moral stability, especially in his constant fight

for the right of life, in times of flux and spiritual uncertainty.

Walesa,

Lech (b. Popowo, 29 September 1943). When Lech Walesa climbed over

the Lenin Shipyard fence in 1980 little did he know that he would set into

motion a wave of political action that would finally free Eastern

Europe from the grip of the Soviets.

Walesa trained as an electrician and worked at the Lenin Shipyards,Gdansk.

During the crisis of December 1970, when food prices rose steeply during

Christmas week leading to strikes and demonstrations against the Government

- most notably in the shipyards of Gdansk, Gdynia and Szczecin, and Gomulka was

forced to resign to be replaced by Gierek; Walesa was

a member of the 27-strong action committee at the shipyards. His activities as

shop steward led to his dismissal in 1976. After Gierek’s

attempts to ease the foreign debt in 1976 failed, a 60% increase in food prices

had to be cancelled because of a series of violent strikes. This, in turn, led

to a backlash; there was greater repression by the Citizens’ Militia (ZOMO) and

severe sentences were imposed on “troublemakers”. As a result, opposition

groups, like KOR (Committee for the Defence of the

Workers), were set up. The economy continued to “overheat” and there was a

period of acute consumer shortages, especially meat, and a soaring foreign

debt. Once again, price rises in July 1980 touched off nation–wide strikes. On

14 August 1980 Walesa climbed into the Lenin Shipyard, Gdansk, to became

leader of a sit-in strike over the illegal dismissal of a fellow worker, Anna Walentynowicz. His experiences in the 1970 strikes and

years of discussion with KOR and underground workers’ cells, had led him to

develop a strategy with defined goals. He demanded that representatives of the

government come to the shipyards to listen to the demands of the workers and

negotiate whilst skilful management of the International Press ensured that the

whole process would be reported and recorded. The idea spread and an

Inter-factory Strike Committee, advised by KOR, was set up in order to co-ordinate

the activity. At the end of August the Gdansk Agreement (31 August 1980)

created Solidarity as an independent, self–managing trade union with access to

the media and civil rights. It was the first authentic workers’ revolution in Europe, ironically directed against the party of the

proletariat. The economic situation worsened and there were acute shortages,

especially in medical supplies. Poland

was saved from mass-starvation by the action of Poles all over the world,

sending food and other supplies. The Party began to fall apart as its

leadership became embroiled in in-fighting and its members left to join

Solidarity. There were struggles within Solidarity itself between those who

wished to consolidate their position and those who wanted to go further; it

began to resemble the situation in 1863. Things came to a head at Solidarity’s

First National Congress (September 1981) - the first democratically elected

Polish national assembly since WW2 - when Walesa and his moderates tried to

limit discussions to matters concerning Solidarity and the Gdansk Agreement

whilst more radical elements wanted to widen the debate to issues of principle.

There was even a motion passed offering sympathy and support to the downtrodden

peoples of the Soviet Bloc. Although the Soviet Union was isolated because of

its involvement in the war in Afghanistan,

and economically dependent on the West, it was inevitable that something would

be done. On 13 December 1981, General Jaruzelski

declared a state of martial law and suspended Solidarity. Walesa was detained

but released and reinstated at the Gdansk

shipyards in November 1982. Gradually, as the country’s political and economic

life returned to normal, martial law was lifted (July 1983). Walesa was awarded

the Nobel Peace Prize (October 1983); the award was attacked by the government

press and Walesa did not go to accept it until 1990 for fear of being refused

permission to return to Poland.

From 1986 onwards, there was great discussion as to the way the country could

develop which led, in 1988, to a referendum and fresh elections which opened

the way to the massive changes of June 1989 when Solidarity won 99 per cent of

the seats in the newly created Senate. Whilst Jaruzelski

was narrowly appointed President by the Sejm in June

1989, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Walesa’s Solidarity

colleague, became the first non-Communist Prime Minister since WW2. In December

1990, Lech Walesa was sworn in as the first non–Communist Polish President

since WW2 (he was defeated in 1995). By now the map of Europe

had been redrawn as Soviet supremacy ended. Walesa has been granted a number of

honorary awards on top of the Nobel Prize including the Medal of Freedom (Philadelphia, US),

the Award of the Free World (Norway),

and the European Award of Human Rights. In November 1989 he became only the

third person in history, after Lafayette and Churchill, to address a joint

session of the United States Congress. In February 2002 he was chosen to

represent Europe and carry the Olympic flag into the stadium during the opening

ceremony at Salt lake

City.

Walesa,

Lech (b. Popowo, 29 September 1943). When Lech Walesa climbed over

the Lenin Shipyard fence in 1980 little did he know that he would set into

motion a wave of political action that would finally free Eastern

Europe from the grip of the Soviets.

Walesa trained as an electrician and worked at the Lenin Shipyards,Gdansk.

During the crisis of December 1970, when food prices rose steeply during

Christmas week leading to strikes and demonstrations against the Government

- most notably in the shipyards of Gdansk, Gdynia and Szczecin, and Gomulka was

forced to resign to be replaced by Gierek; Walesa was

a member of the 27-strong action committee at the shipyards. His activities as

shop steward led to his dismissal in 1976. After Gierek’s

attempts to ease the foreign debt in 1976 failed, a 60% increase in food prices

had to be cancelled because of a series of violent strikes. This, in turn, led

to a backlash; there was greater repression by the Citizens’ Militia (ZOMO) and

severe sentences were imposed on “troublemakers”. As a result, opposition

groups, like KOR (Committee for the Defence of the

Workers), were set up. The economy continued to “overheat” and there was a

period of acute consumer shortages, especially meat, and a soaring foreign

debt. Once again, price rises in July 1980 touched off nation–wide strikes. On

14 August 1980 Walesa climbed into the Lenin Shipyard, Gdansk, to became

leader of a sit-in strike over the illegal dismissal of a fellow worker, Anna Walentynowicz. His experiences in the 1970 strikes and

years of discussion with KOR and underground workers’ cells, had led him to

develop a strategy with defined goals. He demanded that representatives of the

government come to the shipyards to listen to the demands of the workers and

negotiate whilst skilful management of the International Press ensured that the

whole process would be reported and recorded. The idea spread and an

Inter-factory Strike Committee, advised by KOR, was set up in order to co-ordinate

the activity. At the end of August the Gdansk Agreement (31 August 1980)

created Solidarity as an independent, self–managing trade union with access to

the media and civil rights. It was the first authentic workers’ revolution in Europe, ironically directed against the party of the

proletariat. The economic situation worsened and there were acute shortages,

especially in medical supplies. Poland

was saved from mass-starvation by the action of Poles all over the world,

sending food and other supplies. The Party began to fall apart as its

leadership became embroiled in in-fighting and its members left to join

Solidarity. There were struggles within Solidarity itself between those who

wished to consolidate their position and those who wanted to go further; it

began to resemble the situation in 1863. Things came to a head at Solidarity’s

First National Congress (September 1981) - the first democratically elected

Polish national assembly since WW2 - when Walesa and his moderates tried to

limit discussions to matters concerning Solidarity and the Gdansk Agreement

whilst more radical elements wanted to widen the debate to issues of principle.

There was even a motion passed offering sympathy and support to the downtrodden

peoples of the Soviet Bloc. Although the Soviet Union was isolated because of

its involvement in the war in Afghanistan,

and economically dependent on the West, it was inevitable that something would

be done. On 13 December 1981, General Jaruzelski

declared a state of martial law and suspended Solidarity. Walesa was detained

but released and reinstated at the Gdansk

shipyards in November 1982. Gradually, as the country’s political and economic

life returned to normal, martial law was lifted (July 1983). Walesa was awarded

the Nobel Peace Prize (October 1983); the award was attacked by the government

press and Walesa did not go to accept it until 1990 for fear of being refused

permission to return to Poland.

From 1986 onwards, there was great discussion as to the way the country could

develop which led, in 1988, to a referendum and fresh elections which opened

the way to the massive changes of June 1989 when Solidarity won 99 per cent of

the seats in the newly created Senate. Whilst Jaruzelski

was narrowly appointed President by the Sejm in June

1989, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Walesa’s Solidarity

colleague, became the first non-Communist Prime Minister since WW2. In December

1990, Lech Walesa was sworn in as the first non–Communist Polish President

since WW2 (he was defeated in 1995). By now the map of Europe

had been redrawn as Soviet supremacy ended. Walesa has been granted a number of

honorary awards on top of the Nobel Prize including the Medal of Freedom (Philadelphia, US),

the Award of the Free World (Norway),

and the European Award of Human Rights. In November 1989 he became only the

third person in history, after Lafayette and Churchill, to address a joint

session of the United States Congress. In February 2002 he was chosen to

represent Europe and carry the Olympic flag into the stadium during the opening

ceremony at Salt lake

City.

Originally published at http://www.kasprzyk.demon.co.uk/www/HistoryPolska.html

BACK TO POLISH HISTORY

Mikolajczyk, Stanislaw (b. 1903; d. 1966), leader of the Peasant Movement,

founder of the Stronnictwo Ludowe

(the Polish Peasant Party) and representative of the Polish Government-in-Exile

during WW2, offered the only real opposition to the Sanacja

regime established after Pilsudski’s coup. He organised

a political strike (15 August 1937) which called for a political amnesty and a

liquidation of the Sanacja. The strike turned

violent, 42 people were killed and about 1000 arrested; the events shook the

régime badly. When Sikorski was killed at

Mikolajczyk, Stanislaw (b. 1903; d. 1966), leader of the Peasant Movement,

founder of the Stronnictwo Ludowe

(the Polish Peasant Party) and representative of the Polish Government-in-Exile

during WW2, offered the only real opposition to the Sanacja

regime established after Pilsudski’s coup. He organised

a political strike (15 August 1937) which called for a political amnesty and a

liquidation of the Sanacja. The strike turned

violent, 42 people were killed and about 1000 arrested; the events shook the

régime badly. When Sikorski was killed at  Bierut,

Boleslaw (b. Rurach Jezuickich, nr.

Bierut,

Boleslaw (b. Rurach Jezuickich, nr.  Gomulka,

Wladyslaw (b. Krosno, 1905; d.

Gomulka,

Wladyslaw (b. Krosno, 1905; d.  Gierek,

Edward (b. 1913; d.

Cieszyn, 2001), First Secretary of the Polish

Communist Party during the rise of Solidarity, went to

Gierek,

Edward (b. 1913; d.

Cieszyn, 2001), First Secretary of the Polish

Communist Party during the rise of Solidarity, went to  Jaruzelski,

Wojciech (b. Kurow, 1923). Born into a

wealthy land-owning family, Jaruzelski was deported

to the

Jaruzelski,

Wojciech (b. Kurow, 1923). Born into a

wealthy land-owning family, Jaruzelski was deported

to the  Wojtyla, Karol (Pope John Paul II) (b. Wadowice,1920),

the 264th Pontiff, is the first non-Italian Pontiff for 455 years, the first

from a Communist country and the first Polish Pope. His mother died when he was

small and he was brought up by his rather stern father. In 1938 Wojtyla entered the

Wojtyla, Karol (Pope John Paul II) (b. Wadowice,1920),

the 264th Pontiff, is the first non-Italian Pontiff for 455 years, the first

from a Communist country and the first Polish Pope. His mother died when he was

small and he was brought up by his rather stern father. In 1938 Wojtyla entered the  Walesa,

Lech (b. Popowo, 29 September 1943). When Lech Walesa climbed over

the Lenin Shipyard fence in 1980 little did he know that he would set into

motion a wave of political action that would finally free

Walesa,

Lech (b. Popowo, 29 September 1943). When Lech Walesa climbed over

the Lenin Shipyard fence in 1980 little did he know that he would set into

motion a wave of political action that would finally free