|

|

|

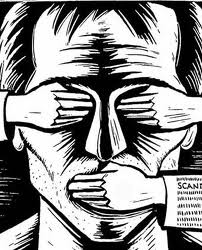

A Deal with the Devil: The Transfer Agreement and the Zionist Pact with Hitler By Tara Douglas

|

|

|

|

Well-documented

but little known research has recently revealed that an alliance between certain

Zionist leaders and the Nazi party of the Third Reich began in 1933 and

lasted until the outbreak of the Second Word War in

1939. This alliance was not only instrumental in the eventual creation of Israel, it also interfered with the establishment of other

safe havens for Jews around the world. And, perhaps most significantly, the

Zionist-Nazi agreement helped to prevent the dismantling of the Nazi regime

in its earliest and most vulnerable stage. For during the pivotal year of

1933, many Jewish leaders around the world believed that in the early months

of the Third Reich, the economy was Hitler’s Achilles’ heel, and they were determined to cause the Nazi

downfall through an international anti-German economic boycott. However,

certain Zionist leaders were even more determined to sabotage these efforts

for their own gain. Both the Nazis, in the short term, and the Zionists, in

the long run, were the ultimate victors. In

1933 the Zionists were still a small minority of the German Jewish population

and, indeed, of the Jewish population worldwide. Although well organized and

highly vocal, the World Zionist Organization was basically a fringe movement

that found support in approximately two percent of German Jews. Essentially

and fundamentally, the majority of the population of Jews considered the

philosophy of Zionism to be “self-segregating, ghettoizing practices

converging in a core of … ‘Jewish’ nationalism.”9 Zionism had come into existence as an

organized political movement in 1897, and had been formulated within an

environment and during a century of intense nationalistic development in

Europe. Under the auspices of Theodor Herzl, an Austrian Jew and the founder

of the movement, Zionist ideology transformed Judaism from a religion into a

national and political ideal. Despite a varied and heterogeneous history in

the two thousand years since the Jewish Diaspora,

Herzl believed that all Jews had a common past and a common destiny. Herzl

postulated and promulgated the theory that Jews were a separate and distinct

nation, one which could not accommodate itself, nor be accommodated, to life

among other nations. Therefore, the only way to solve “the Jewish problem” was

for the Jews to have a country of their own.10 Although there were always

divergent opinions among Zionists about where and how to fulfill their aims,

during the decades following the movement’s inception, Zionist adherents in

Germany became increasingly radicalized. This extremism escalated to such a

degree that many liberal and humanitarian Zionists disassociated themselves

from the movement.11

Yet, in the radical views that became part of the official German Zionist

Federation doctrine, assimilation was identified as the dominant enemy of the

Jews, and this belief was based on the conviction that “all efforts to blend

with non-Jews must lead unswervingly to deformed Jewish life.”12

At the heart of

Zionist conviction lay the belief that Jews comprised a unique

race, as opposed to a mere ethnicity. Although the doctrine of racial

superiority was never officially adopted, German Zionists expressed a Jewish

version of the Nazi doctrine of Aryan superiority, and claims of Jewish

moral, spiritual, and intellectual advancement in comparison to other races

formed a large part of Zionist propaganda. German Zionists also believed Jews

to be a pure race, since Jewish religious leaders had always frowned upon

intermarriage, which threatened racial purity. Since Jews believed themselves

to be the ‘Chosen People,’ they had historically kept themselves separate and

apart from other races, as well as having had separation forced upon them.13 The

German Zionist philosophy also paralleled the Nazi doctrine in other respects.

Zionist ideology incorporated its own version of the German volkgeist. To

Zionists, Jews were a volk,

both a race and a nation.14

During the early part of the twentieth century, this Jewish version of the

German vision of “blood and soil” took hold. But although Jews had the

“blood,” they were missing the “soil”. This lack inspired many European

Zionists to adopt the views of the Russian Zionist Asher Ginzberg,

who believed that Palestine, the Jewish homeland two thousand years earlier,

was the true location of the Jewish nation-state that Herzl envisioned. This

view culminated during the 1912 World Zionist convention in Posen, with the

passing of a resolution calling for every German Zionist to plan to emigrate to Palestine and to abolish all ties with

Germany, since Jews had no “roots” in Germany. The passion generated by these

views provoked Polish Jew and Zionist leader, Vladimir Jabotinsky,

to later exclaim at the Twelfth Zionist Congress of 1921, “In working for

Palestine, I would even ally myself with the devil.”15 By 1933, despite the fact that the great

majority of German Jews had no interest in going there, Palestine was the

epitome of German Zionist aspirations. The

first wave of European Jewish immigration to Palestine following the creation

of the World Zionist Organization began in 1904. But it was not until the

creation of the British Mandate of Palestine, established after WWI primarily

as a result of the collaboration between British Zionists (under Chaim Weizmann) and the British government,

that Jews living in Palestine were permitted to have their own

political governing body. This governing body was known as the Jewish Agency.

Although somewhat autonomous, the Jewish Agency was essentially directed and

controlled from London. The Jewish Agency had evolved during the 1920s from

the Zionist Commission, which had originally been created by the British in

1919, as part of their own imperialist interests in the Middle East. The

British supported the Zionists for well over a decade, but the conflict

between the Arabs, who had inhabited this region for hundreds of years, and

the European Jewish settlers was escalating to such an extent that by the

1930s the British began to make it increasingly difficult for Jewish

immigrants to come to Palestine, unless they were “capitalist” settlers in

possession of $5,000 (or L1,000).32 And despite almost three decades of Zionist

efforts to mobilize world Jewry to immigrate to Palestine, by 1933 there were

just 200,000 Jews living in Palestine, comprising only nineteen percent of

the population.33 The Zionist leaders in Palestine,

therefore, believed that in order to achieve their national and political

aims, it was essential to increase the Jewish population. They considered the

situation a race between Arabs and Jews, and they were determined to win that

race.34 And the Zionists were also determined not to

be out-manoeuvred by the British. Meanwhile,

in the United States, there were two main Jewish defense

organizations as of March 1933. The American Jewish Committee had been

founded by wealthy German Jews in 1906, and was comprised of assimilated Jews

who considered themselves superior to the Jews of Eastern Europe. Although

the Committee had only 350 members, it had money and political influence. The

American Jewish Congress was essentially an Eastern European Jewish

organization, founded by Rabbi Stephen Wise. The Congress represented a much

larger constituency and was much more politically vocal than was the

Committee, but it was also much less financially viable, and therefore, less

influential. However, both organizations were aware that they potentially

possessed one weapon that Hitler most feared – an economic boycott.3 An

international economic boycott against German goods and services would be disastrous

to the newly formed Nazi government, as Hitler’s election platform was based

on the promise of substantial economic improvement. The Jewish organizations

had a history of successfully using the weapons of boycotts and protests to

fight anti-Semitism, including a boycott against one of America’s richest

men, Henry Ford.4 Even Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Propaganda

Minister, was concerned about this mounting threat, about which he wrote in

his diary, “We are defenselessly exposed to the

attacks of our adversaries.”5

However, this time the Committee, because of its associations with Germany

and its fear of Nazi reprisals on German Jews, preferred diplomatic action.

The Association of Jewish War Veterans, the Congress, and Jews around the

world wanted to take a more aggressive public stand. The

protests began quickly. On March 20, Polish Jews organized a large

rally. On March 23, thousands of Jews

came out to take part in a boycott parade in New York City, and thousands

more people cheered from the sidelines. On March 27, a huge protest took

place in New York City that was coordinated with 80 other cities throughout

the USA, while millions listened to live broadcasts. Anti-Nazi boycott

movements were growing worldwide, and not only among Jews. Countries like

Lithuania, France, Holland, Britain, and Egypt were organizing protests and

displaying signs that said: “Boycott German Goods.” Steamship lines in New

York cancelled bookings with German companies. Labour unions put up boycott

posters all over London. The international Jewish leadership, spearheaded by

Wise, began to plan a much more massive boycott.6 The

Nazi reaction to this economic threat was swift. On March 23, Hitler gave a

speech which focused on Germany’s desire for good international trade relations,

in which he stated that “Germany needs contact with the outside world and

foreign markets – otherwise we cannot regulate our foreign debt.” 7

On March 25, Hermann Goering, Minister of the Interior, summoned the leaders

of several German Jewish organizations to his office for a meeting.8

No Zionist representatives were invited. When

German Zionist leaders found out about the meeting with Goering, Kurt Blumenfeld, president of the German Zionist Federation,

arranged to attend. Goering threatened severe reprisals unless the German

Jewish community put a stop to the looming economic boycott. The Nazis had

devised an anti-Jewish boycott of their own, which would begin on 1 April

1933 and would end when anti-German boycotts in New York and London also

ended. Only Blumenfeld was capable of meeting with

other Jewish world leaders, since the Zionists were part of an international

organization whose headquarters were in London, and whose branches existed in

numerous other countries. The Zionists then set about to deny the atrocities

that were taking place under the Nazis, and to put a halt to the boycott.16 While

the German government struggled in private over how to handle economic

boycotts, the German Zionist leaders in London also schemed and plotted behind

the scenes. Unable to get any support for their anti-boycott efforts from the

World Zionist Organization headquarters, the German Zionists sent a false

telegram to the Jewish Agency, the arm of the Zionist Organization in

Palestine and an official advisory body to the British mandatory government

there.20 Pretending to be the Executive Committee of

the World Zionist Organization, the German Zionists told the Jewish Agency to

cable Hitler and tell him that the Agency was not in favour of an anti-German

boycott. The telegram was also a message to the Zionist membership in

Palestine that their international leadership opposed the boycott. The Jewish

Agency did as they were directed.21 What

official Zionists in London also did not know was that on 16 March 1933 a

meeting had taken place in Palestine that was destined to change the course

of Palestine’s history. On this date four men from the Jewish Agency

(including Felix Rosenbluth, a former president of

the German Zionist Federation and the future state of Israel’s first Minister

of Justice) met to discuss issues of finance. The world response to Jewish

persecution in Germany was so vast that Jewish defense

and refuge organizations were receiving huge amounts of funds. However, none

of these funds were earmarked for the Zionist cause. The Agency Jews were

concerned about how to prevent these donations from stabilizing German Jews

or allowing Jewish immigration to other parts of the world. Despite

subsequent Zionist propaganda, many other opportunities for Jewish settlement

did exist. One mass resettlement in particular was being planned for South

America by the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Society (HIAS) and the

Zionists believed that this project was taking vast amounts of money away

from the Agency. The Jewish Agency had to act because its financial situation

was desperate. If circumstances continued unchanged, it would soon be facing

bankruptcy. As one of the meeting’s participants complained in regard to

another American agency, two million dollars in relief aid was raised, and

there was not one Zionist among the trustees. To counter this situation, the

Jewish Agency leaders decided to create a new refugee fund with Zionist

trustees but without any outer identification with either Palestine or Zionism.

They wanted Chaim Weizmann, who was no longer an

official of the World Zionist Organization, to run the new fund.35 Although

getting a share of the donated funds was an important issue, another problem

was pressing on these men’s minds. The Zionist leaders in Palestine were also

worried that German Jews with money would go to other countries, and that

Jews without means would end up in Palestine. Yet wealthy middle class Jews

who did want to leave Germany were hampered by a currency restriction that had

been imposed on all Germans in 1931, which prevented money from leaving the

country without permission. Middle class Jews had the means to pay the

British entry requirements to Palestine, but they would not want to leave

their assets behind in Germany. It

was then that the Agency’s Felix Rosenbluth made

the crucial suggestion: perhaps the Zionists should try to negotiate with the

German government for special concessions for wealthier Jews who would

emigrate to Palestine. The Jewish Agency needed these Jews and their money. A

few days later, Sam Cohen, an influential German Jewish businessman who was

also a non-Zionist, was commissioned by the Agency to undertake the secret

negotiations between the Zionists and the Nazis.36 Thus, in late March, Sam Cohen began to negotiate the first stages of what was to become known as the Haavrara or Transfer Agreement.37 After arranging meetings with two German government officials, Cohen asked for special currency exemptions for Jews who wanted to emigrate to Palestine. Terms were agreed upon which were weighted heavily in favour of the German government. Middle class Jews would liquidate their assets and then give all their money to the government, in the form of taxes or in frozen bank accounts, with the exception of the $5,000 needed for entrance to Palestine. In exchange, the Zionist movement would actively block the anti-German boycott and would also promote German exports, thereby increasing foreign currency in Germany.38 The agreement did not satisfy George Landauer, a director of the German Zionist Federation and one of the few people who knew about the arrangement.39 He wanted more money for Palestinian Zionists. And although the German government was initially supportive, in a few short weeks the agreement fell apart. Pressure on the arrangement began as soon as

the 1 April anti-Jewish rally took place as planned. Throughout April, the

Nazis also put legal measures in place that took rights and work away from

German Jews.40

These actions inflamed an international Jewish demand for economic reprisals

against Germany. Despite the anti-boycott stance of the Zionist leaders in

Palestine, the Jewish population there had refused to follow their leaders’

instructions and actively supported the boycott. These Jews cancelled orders

for German agricultural equipment and other German exports, and did

everything they could to damage all German economic activities. By mid April

the German government cancelled the exemption agreement because the Agency

Zionists who had concocted this plan had not kept their side of the bargain.

The boycott momentum was growing, not diminishing.41 In

early May, Cohen met with the same government officials, pretending to

represent the official Zionist Leadership. He hired Siegrfried

Moses, head of the German Zionist Federation, to accompany him, in order to

lend credence to his ruse. This time Cohen offered the Nazis an even better

arrangement, based on the use of his own company, Hanotaiah

Ltd.42 Wealthy and middle class Jewish emigrants

would swap their accounts with other foreign currency buyers, less the

required taxes. Palestine Zionists would control a share of the funds, and

they would then buy farm equipment, pipes, chemicals, and other German goods

with the money from these blocked accounts, through Cohen’s company. The new

Palestinian immigrants would be given land (bought cheaply from Arab

landowners) and farm equipment, in exchange for giving up their money. Thus

all the Jewish assets would be divided between Palestine and the Third Reich,

in Germany’s favour. The agreement appealed to the German government. The

Nazis would get Jewish money; increased trade (since emigration was linked to

the purchase of goods); a doorway into the expanding Middle Eastern market;

increased domestic employment; and the removal of Jews, all in one fell

swoop. The Jewish immigrants would be forced to work the land and develop

Palestine, in what would amount to indentured servitude, since they would

have no money. To the Zionists, that would be a small matter, since labourers

were needed in Palestine, not merchants.43 A

short time after the Transfer Agreement was arranged, the operation of the

arrangement was taken over by Agency and German Zionist leaders and the

Anglo-Palestine Bank, which agreed to front for the Zionists. At the

Eighteenth World Zionist Congress, held in August of 1933, a surprised

Zionist membership was asked to vote on and pass the Transfer Agreement, and

work to establish a state of Israel in Palestine, which would adopt the

Zionist symbol as its new flag. With the Agency’s success with the Agreement,

all efforts would now be directed at getting German Jews to immigrate to

Palestine and to develop Israel. However, the majority of German Jews were

anti-Zionist, had no interest in Palestine, and wanted to fight for their

rights in Germany. But the Transfer Agreement was not a rescue or relief

project for the Jews in Germany, and the Zionists had little concern for the

agreement’s impact on the Jews there. The Zionist leaders were unwilling to

protect Jewish rights in Europe just at the time when that course of action

was most needed. They wanted money and labour to build up Palestine, and

their main concern was for the German Jews who did want to emigrate there.44 In

order to boost immigration, new strategies were needed. Chaim

Weizmann started a new organization, the Central Bureau for the Settlement of

German Jews. This organization, which worked out of London, coordinated

efforts between Palestine and the German government, and made all life and

death rescue decisions for the following fifteen years. Palestine needed

young, strong, healthy workers. This need became a primary factor in

determining which Jews were accepted, and which were rejected as settlers in

Palestine.45

In her book, Eichmann in Jerusalem, Hannah Arendt

verified the intimate connection between the Nazis and the Zionist leaders,

who were the only Jews in the early months of the Hitler regime to associate

with the German authorities and who used their position to discredit

anti-Zionist and non-Zionist Jews. According to Arendt, the German Zionists

urged the adoption of the slogan, “Wear the yellow star with pride” to end

Jewish assimilation and to encourage the Nazis to send the Jews to Palestine.46 And

although at that time many countries were willing to take Jewish refugees,

Zionist propaganda successfully convinced many German and European Jews that

there were no other places to go Countries as disparate as Australia, Crimea,

Ukraine, and Manchuria, as well as South American and African countries

offered to accept refugees. The World Zionist Organization rejected them all.

The Zionist leadership even fought for German regulations to prevent German

Jews from saving their wealth in any other way than through investing in

Palestine. As the amounts of transferred funds grew, it was not long before

what began as a “noble” ideal of building Palestine into a Jewish homeland

disintegrated into a situation of commercial and business opportunities, with

a rush of entrepreneurs anxious to control the capital of captive German

Jews. All the while, Hitler was growing stronger and Nazi evil was spreading.46 The

alliance with Germany, based on trade, shifted Zionist priorities from a

people caught in a crisis to money caught in a crisis. The Zionists knew that

the success of the Agreement was dependent upon the survival of the Nazi

economy. The economy needed to be stabilized and safeguarded, because if the

Nazis fell, the Zionists would be ruined. As well as investing in Palestine,

the Zionists invested the transferred funds in major German companies and in

enterprises like the railways. And Zionist leaders in London, New York and

Germany worked very hard to prevent the economic boycott from happening.

Cohen devised a system of safeguarding, in his bank accounts, money belonging

to Jews who wanted to emigrate later on, and he used the money to break

boycott support in other areas. As well, pro-Palestine propaganda developed

in full force. Penniless refuges in Europe were straining the resources of

other countries’ charitable organizations, such as those in France, Holland,

and Czechoslovakia, since, with the help of Chaim

Weizmann, money had been successfully diverted from other relief

organizations into Zionist hands. Now Jews in these and other countries were

being told by Weizmann that caring for German Jewish refuges was tantamount

to importing anti-Semitism into their countries. He even mimicked Hitler’s

rhetoric and called the refugees “germ carriers of a new outbreak of

anti-Semitism.” Of course, there was only one answer to this problem:

Palestine.47 Meanwhile,

although international support had been amassing all summer, Rabbi Wise of

the American Jewish Congress, one of the boycott leaders, had dithered and

delayed about announcing the huge boycott, caught under opposing pressure

from boycott supporters on one hand, and the Zionists and the American Jewish

Committee on the other. Finally, the international Jewish leadership, which

had been planning and organizing for the boycott for months and had wanted to

announce the boycott’s inauguration, at the very latest during the Second

World Jewish Congress in Geneva in September, were instead directed to turn

over all political affairs to the Paris-based Committee of Jewish Delegations,

a Zionist group. With this decision, the leadership of the worldwide boycott

was handed over to the Zionists. Wise had caved in to the Zionist pressure.48 When a boycott did occur over the

winter, it was haphazardly funded and organized by a few die-hards. But it

was too little, too late, to really affect the German economy or to lessen

Hitler’s hold on the reigns of power. However,

thanks to the Transfer Agreement, the Jewish population in Palestine tripled

in three short years and Jewish Palestine began to flourish with young German

émigrés, and the reconstruction that their capital contributed. By 1939, ten

percent of German Jews had moved to Palestine and 140 million RM had been

transferred.49

Towns and settlements had grown up along the coastal plain of the

Mediterranean, and Haifa was a bustling German immigrant city. Palestine was

on its way to becoming a Jewish state. The Transfer Agreement was renewed in

February of 1934, and, due to the great success of their enterprise, the

Zionists created another company, the Near and Middle East Commercial

Corporation (NEMICO) which opened German expansion throughout the Middle

East.50

But, by the end of the decade, circumstances had changed. For the Nazis, the

exodus of the Jews from Germany was taking place too slowly. And the rest of

the world, now seemingly saturated with 100,000 penniless Jewish refugees,

began to close its doors. Based on what is now known, it can

be argued, although it is certainly not a popular argument to make, that if

the world’s Jews had organized and united, they might have had an excellent

chance of containing, if not toppling, Hitler’s regime in early 1933. The

economy was a critical issue in Germany at that time, and American companies

controlled much of German industry. If the German economic depression had

deepened, Hitler would most likely have been blamed and another coalition

government would have been forced to form. The retribution on German Jews

would most likely have been extreme. But it would have been visible, with

greater likelihood of international intervention. And it would hardly have

compared to the slaughter that the German and other European Jews ultimately

experienced. But the Zionists, in their subterfuge, were successful in

opposing the boycott and the window of opportunity, which could have been

seized, was quickly closed. After September 1933, it was too late. However,

what actually occurred was that the Zionists were successful in fulfilling their

own ambitions for Palestine. The Transfer Agreement and the Zionists’

economic relationship with the Nazi regime, with all its ramifications, was

an indispensable factor in the creation of Israel. Through the Transfer

Agreement, the Zionists were able to build up Palestine’s Jewish population

and infrastructure. They were able to focus world attention on the viability

of Palestine as a homeland for the Jews. They skilfully inculcated the

belief, among Jews and Gentiles alike, that there were no other options and

that a return to Palestine was something all Jews had longed for, for the

previous two thousand years. When the atrocities of the Holocaust were

revealed, the Zionists were ready to take advantage of this opportunity, and

they again presented Palestine to the world as the only viable alternative for Jews. BIBLIOGRAPHY: Arendt,

Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem New

York: Viking Press, 1963 Barkai, Avraham.

From Boycott to Annihilation – The

Economic Struggle of German Jews,

1933 –1943.

Hanover: University Press of New England, 1989 Ben-Elissar, Eliahu. La Diplomatie du

III Reich et Les Juifs, 1933-1939. Geneve: Julliard, 1969

Berger,

Elmer. Judaism or Jewish Nationalism,

The Alternative to Zionism. New York: Bookman Associates, 1957 Black,

Edwin. The Transfer Agreement: The

Untold Story of the Secret Pact Between the Third

Reich & Jewish Palestine. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1984 Haim, Yehoyada.

Abandonment of Illusions – Zionist

Political Attitudes Toward Palestinian

Arab Nationalism, 1936-39. Boulder: Westview Press,

1983 Kimche, Jon. Palestine or Israel. London:

Secker & Warburg, 1973

Niewyk, Donald. The Jews in Weimar Germany.

Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

University Press, 1980

Sodaro, Michael and Nathan Brown. Comparative Politics, A Global

Introduction. Boston: McGraw Hill, 2002 The

American Jewish Committee. The Jews in

Nazi Germany. New York, 1935 The

Royal Institute of International Affairs. Great

Britain and Palestine 1915-1945. London: 1937 |

|

|