|

|

Loyal to his Safavid

overlords, Rostom managed to expand the autonomy

of Georgia

within the disintegrating empire. He supervised the revival of trade and the

growth of cities. Iranian influence grew in eastern Georgia, as Kartli-Kakheti's fate was tied ever closer to that of the

empire. Rostom was opposed by the indefatigable Taimuraz until the latter was forced finally to flee Kakheti in 1648.35 To his people Rostom

left a legacy of cooperation with the Iranians and the benefits to be derived

from acceptance of the status quo, but it was not an example that his

successors were willing to follow.

In the second half of the seventeenth century attempts by Georgians to alter

the status quo - to unite the divided kingdoms or to replace Muslim with

Russian overlordship—were successfully thwarted by

the Ottomans and Safavids. The vali of Kartli, Vakhtang

V (Shahnavaz 1; 1658-1676), tried to find a throne

for his energetic son, Archil, first in Imereti (1661) and later in Kakheti

(1664-1675), but ultimately the restless prince was driven into exile in

Russia. Much more successful were those princes and nobles of Kartli-Kakheti who found

positions in the Safavid civil and military

service, even as the empire was threatened by invasions from the east. Giorgi XI of Kartli (1676-1688,

1703-1709) enjoyed a splendid career as the Iranian commander in chief of the

Afghan front. Known as Gurjin Khan, Giorgi led an Iranian-Georgian army against the rebel Mir

Wais. The clever Afghan surrendered without a fight and invited Gurjin Khan to a banquet; there he had his Georgian

guests murdered.

Others in Safavid

service fared better than Giorgi. A French

missionary noted toward the end of the century that the shah "knows how

to keep [the Georgians] divided by self-interest. He promotes all the great

nobles in such an advantageous manner that they forget their fatherland an d their religion to attach themselves to him. The

greatest posts of the empire are today in their hands." Chardin reported that "the greatest part of the

Georgian lords are outwardly Mahometan; some

professing that religion to obtain preferment at court and pensions of

state. Others, that they may have the honor to

marry their daughters to the king, and sometimes merely to get them in to

wait upon the king's wives."

Vakhtang VI,

King of Kartli

Diplomats: Artemis Volunski

(left) and Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani

(right)

The choice faced by all rulers of early modern Georgia was between faithful

service to their Muslim sovereigns or pursuit of the elusive prize of

independence. The history of eighteenth-century Georgia is dominated by two

extraordinary monarchs, Vakhtang VI and Erekle II, who between them managed the affairs of their

realms for nearly three-quarters of the century. Both were, for a time,

successful servants of their Iranian sovereigns, yet when opportunities were

presented by civil wars in Iran,

both sought the phantom aid promised by Russia's autocrats. From 1703, Vakhtang ruled as regent for his uncle, Giorgi XI, and his brother, Kaikhosro

(1709-1711). His administration was distinguished by long-needed reforms and

the collection of laws (dasturlamali) that he had

compiled in 1707-1709. Then, when he should rightly have received the shah's

sanction to ascend the throne of Kartli, Vakhtang thwarted custom by refusing to convert to Islam,

as his predecessors had nominally done. For two years he was a virtual

prisoner in Isfahan while his convert brother,

Iese (Ali-Quli-Khan),

ruled in Tbilisi.

To maintain his faith, Vakhtang sent his learned

uncle and tutor, Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani,

to France

to plead with Louis XIV to put pressure on the Iranians. But nothing came of

the mission, and Vakhtang reluctantly converted in

1716. Almost immediately, however, Vakhtang made contact

with the Russian ambassador, Artemis Volynski, and

informed him of his true religious and political convictions. Not long after

his return to Georgia, Vakhtang declared his support for Russian intervention in

Transcaucasia. Clearly, Kartli's

leaders, like the Kakhetian kings of the preceding

century, calculate continued decline of Iran

and the expansion of Russia

to the south. After a series of delays, Peter the Great, buoyed by his recent

victory over the Swedes, led a small force of Russians south from Astrakhan in 1722. The

moment was well chosen, for the Iranians were engulfed by chaos, as Isfahan had fallen to

the Afghans. Vakhtang refused to come to the aid of

the Iranians preferring to await the arrival of the Russians.

|

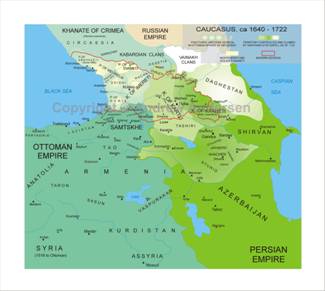

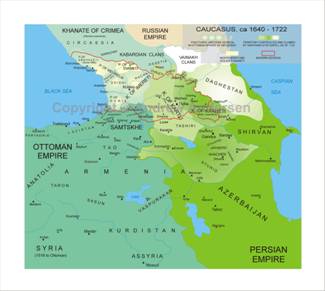

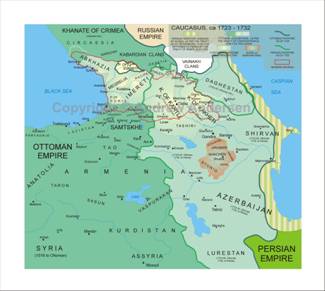

Click

on the map for better resolution

|

|

Unfortunately for the Georgians - and

for the Armenians of Karabagh, also engaged in a

complex struggle against the Muslims—Peter's campaign stopped short of

linking with the Christian rebels, and the tsar withdrew so as not to

antagonize the Turks. Vakhtang was left exposed and

alone. Facing a Turkish invasion and opposed by the king of Kakheti, Konstantin, to whom the shah had given the

throne of Kartli as well, Vakhtang

was forced to evacuate Tbilisi.

He made his way across the Caucasus to Russia, where he died in 1737.

The first Russian invasion of Transcaucasia

thus proved a disaster for the pro-Russian elements among the local Christian

people. The most immediate result was the establishment of Turkish authority

throughout Caucasia, the brief but terrible

period known in Georgian as the osmanloba (1723-1735).

|

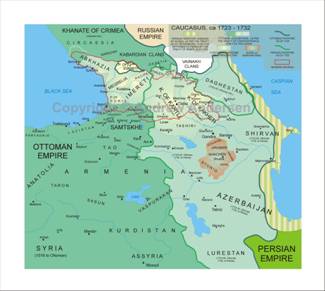

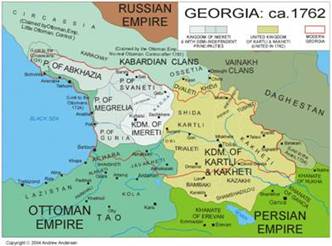

Click

on the map for better resolution

|

|

Despite their own misfortunes, the Iranians were unwilling to cede eastern

Georgia to the Turks, but until the rise to power of the rough and able

soldier, Nadir, they were unable to prevent this loss. The revival of Iranian

imperialism began in the 1730s and coincided with Georgian resistance to the

Turks. In 1732, Konstantin of Kakheti made a fatal

attempt to break with the Turks and was murdered. The Turks gave his throne

to his brother, Taimuraz II (1732-1744), thus

laying the ground for the eventual reunification of Kartli

and Kakheti.39 The next year the Abkhaz dealt the Turks a devastating blow in

western Georgia, and in

1734-1735, Nadir made two campaigns into Transcaucasia.

Taimuraz defected to the Iranians, and together the

Iranian-Georgian forces liberated Tbilisi

in August 1735. The osmanloba

was replaced by the kizilbasboba

(rule by the kizilbash,

or "redheads," as the Safavids were

known).

Taimuraz,

King of Kakheti

As long as Nadir Shah (1736-1747) dominated Iran,

the Iranians were able to maintain their sway over eastern Georgia, Armenia,

and Azerbaijan.

The Russians, who in the post-Petrine period had

neither the interest nor the ability to hold their outposts in the Caucasus,

signed a treaty by which they abandoned the conquests of Peter the Great

south of the Sulak River.

Taimuraz ruled in Kakheti

as an Iranian governor, while his son, Erekle,

campaigned for Nadir in India.

The Iranian governor of Kartli, Killij-Ali-Khan

(Khanjal), levied new taxes on the Georgians to

finance Nadir's wars. Peasants migrated westward to escape the new burdens,

and prominent nobles, like the eristavi of Ksani, Shanshe, and the vakili (ruler)

of Kartli, Givi Amilakhori, rose in rebellion. Taimuraz

and Erekle joined forces with the shah and helped

to defeat their rebellious countrymen. As a reward, Taimuraz

was crowned king of Kartli (1744-1762), and Erekle became king of Kakheti

(1744-1762). Thus, all of eastern Georgia was ruled by Kakhetian Bagratids, father

and son, but Nadir Shah, their overlord, continued to Impose new taxes on his

Georgian subjects. In 1746 Kartli-Kakheti was required to pay three hundred thousand tumanebi in

tribute. When, the next year, Nadir was murdered in his tent while on a

campaign in the east, Iran fell into civil disarray, and the wily Bagratid kings of Kartli-Kakheti found themselves arbiters of Transcaucasian

politics. In the vacuum left by Iran's

troubles and Russia's

withdrawal, Taimuraz II and his son set out to

rebuild Georgia

and create a multinational Caucasian state

|

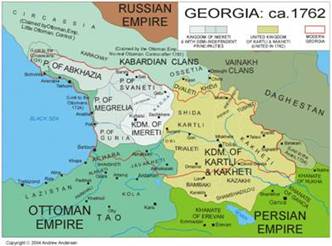

Click

on the map for better resolution

|

|

Transcaucasia

in the mid-eighteenth century was a mosaic of kingdoms, khanates, and

principalities, nominally undr either Turkish or Iranian

sovereignty but actually maintaining varying degrees of precarious autonomy

or independence.

Taimuraz and Erekle were

faced by three sources of opposition to the expansion of their authority:

Georgian rivals, particularly the exiled Mukhranian

Bagratids; ambitious Muslim khans of eastern

Transcaucasia; and mountaineers from the North Caucasus, who raided the

Georgian valleys.

|

|