|

|

|

Soviet-Georgian War and Sovietization

of La guerre soviéto-géorgienne

et la soviétisation de la Géorgie

(février-mars 1921) By

Andrew Andersen and George Partskhaladze Photographs: private archive of Levan Urushadze |

|

|

|

Introduction In the year 1918, Initially, the Georgian elites were

reluctant to separate from

Military parade in Tbilisi, January/1921 During the three years of independence,

Georgia’s moderate socialist leadership were rather successful in the

establishment of a democracy-track society with universal suffrage,

democratically-elected legislature, freedom of speech and tolerance to both

right- and left-wing opposition[2].

However, the development of democratic processes in the First Republic faced

a number of challenges that included involvement in military conflicts with

Turkey, Armenia, as well as “the Reds” and “the Whites” of Southern Russia,

economic blockade by Western powers, delay of international recognition until

early 1920, internal conflicts with some ethnic minorities and subversive

activities of local Bolsheviks encouraged by Moscow and following orders from

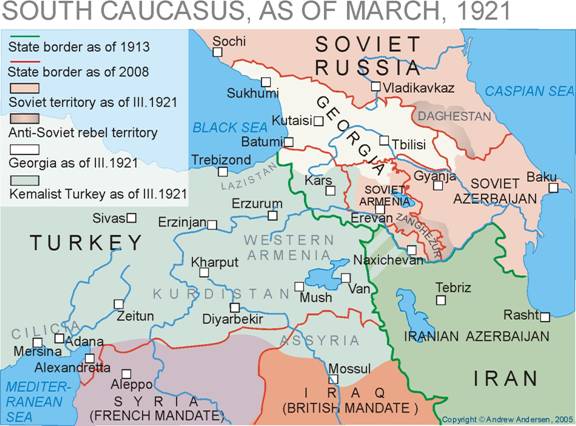

the Kremlin[3]. By the end of February, 1920, an alliance

was formed between the Kemalist government of

Beginning

of the War In February 1921, the Soviet Red Army

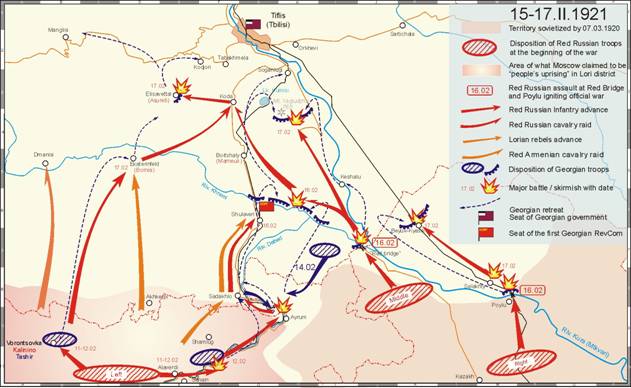

invaded The massive assault on On February 11, 1921, Soviet Russian and

Soviet Armenian troops percolated into Georgian-controlled Borchalo and with

some support of the local population hit Georgian garrisons in Sanaini and

Vorontsovka (Tashir). Caught by surprise and heavily decimated, Georgian

units retreated north- and westwards. During the next 68 hours they got

limited reinforcement (one battalion only) and made an abortive attempt to

regain control over the lost territory. After the failure of their counterattack,

the Georgians fell back further north of the line Ayrum – Sadakhlo (Sanaini

group) and towards Ekaterinenfeld (Vorontsovka group). Click on the map to get high resolution image On February 16 the Soviet troops including

the regiments of 96th, 60th and 20th Rifle

Brigades of Russia’s 11th Red Army, Soviet Armenian Mounted

Brigade and several detachments of local Bolshevik sympathizers entered the

village of Shulaveri some 25 km to the north-west of Armenian border and the

so-called “Revolutionary Committee of Georgia” consisting of Red commanders

and local Bolsheviks was formed in the village. The same day, it declared

itself to be the only legitimate government of

Georgian officers David Sarjveladze

and Akaki Skhirtladze

Georgian soldiers At the same time, Soviet Russia’s 98th

Rifle Brigade with Tersky Mounted Division was preparing to attack Soviet

To contain the above invading force, Georgia could put

forward some 11 000 men of the 1st and 2nd Rifle Divisions, a

Mountain Artillery Division, 1st Sukhumi Border Regiment, 2nd

Border Regiment and a dozen battalions of People’s Guard the latter being

civilian militia lacking proper training, command and discipline. Georgian

defense forces had 46 pieces of artillery, several hundred machine guns

(exact number unknown), 4 armored trains, several tanks and armored cars

(exact numbers unknown) and almost no cavalry (only 400 mounted troops) that

could prove quite useful in the mountainous landscape of the country.

Georgians also had several modern airplanes that were of much better quality

than those in possession of the Red Army. However, due to the absence of

proper oil and spare parts that the government refused to purchase, Georgian

pilots were incapable of taking full advantage of their technical superiority[5].

Click here to continue |

|

|