|

|

TOWARDS

GEORGIAN

INDEPENDENCE:

1917-18

Abdication of Nicholas II--Kerensky and the

Georgian SocialDemocrats--Economic change and social revolution--Restoration

of the Georgian Church--Disintegration of Russia's Caucasian Front--Short

rations and Bolshevik broadsheets--The Bolsheviks seize power--The

Transcaucasian Commissariat--The Turkish menace--Brest-Litovsk repudiated--An

ephemeral federation-Germany takes a hand--Birth of the Georgian Republic

Abdication

of Nicholas II

THE STRESSES of World War I precipitated

the Russian political débâcle which many observers had long predicted. In

March 1917, when the revolution ultimately took place, the fall of Tsardom

was comparatively effortless. Bread riots in Petrograd

were followed by a mutiny of the garrison there. The Duma refused to obey the

Tsar's orders any longer. A provisional government was formed on 14 March,

and Nicholas gave in and abdicated without a struggle.

When the news of the revolution reached Georgia,

the fabric of authority crumbled and collapsed. In Tbilisi and elsewhere, the police vanished

from their posts and administrative offices closed down. Bands of

revolutionaries appeared from their hiding places. Mass meetings were held in

the principal towns, at which fierce mountaineers and grimy workers

fraternized and congratulated one another on the achievement of their

longed-for freedom. The once formidable viceroy, Grand Duke Nikolai

Nikolaevich, haggard, with bloodshot eyes and trembling hands, declared to

the local representative of the British fatherland. To the Georgian

Social-Democrats Zhordania and Noe Ramishvili, the grand duke expressed the

hope that he might himself be granted a seat in the Constituent Assembly

which would be called upon to decide the future organization of the Russian

state. However, this was not to be. Nikolai Nikolaevich was very soon

relieved of his post by the new Petrograd government, and politely escorted

to Tbilisi

railway station by squads of cheering soldiers waving red banners and singing

the Internationale.

Aware of the urgency of establishing some

form of authority in Transcaucasia, the Provisional Government in Petrograd

formed a special committee, consisting in the main of Caucasian members of

the Duma, to exercise civil power in Georgia,

Armenia and Azerbaijan.

The chairman of this committee, the so-called Ozakom, was B. A. Kharlamov. At

the outset its only Georgian member was Prince Kita Abashidze.

Kerensky

and the Georgian Social-Democrats

Representations by the Tbilisi

socialists later brought about the co-option of Akaki Chkhenkeli, the

Georgian SocialDemocrat, who also acted as the Petrograd Soviet's Commissar

for Caucasia and on the Turkish military

front. The Ozakom has been described as 'a collective Viceroy, only much

weaker and without the prestige which the representatives of the Tsars had

enjoyed'. 92

One of the sources of weakness of the Kerensky government in Russia

was incessant rivalry between the administration and the Soviets, both of

which regarded themselves as the true repositories of revolutionary power. A

similar dualism existed in Transcaucasia.

Everywhere selfappointed revolutionary bodies sprang up, ready to assume

various functions of government. Among these we may mention the executive

committees of the cities of Tbilisi and Kutaisi, which represented a wide

range of social groups and classes, and normally obeyed the directives of the

Ozakom, and the Tbilisi Soviet of Workers' Deputies ( Chairman, Noe

Zhordania), in which the Georgian Mensheviks had a decisive majority and to

which as time went on deputies of the soldiers and peasants also adhered.

Economic

change and social revolution

As during the 1905 revolution, the Georgian

revolutionary organizations behaved during the trying circumstances of 1917

with moderation and public spirit. They lent their influence to keeping the

peace, preventing inter-communal strife, and bringing about social and

economic reforms in the midst of the war conditions and general upheaval. The

leading Georgian SocialDemocrats renounced for the time being the extremist

slogans of Bolshevik class war and came out on the side of national unity.

'The present revolution,' Zhordania

declared on 18 March 1917, 'is not the affair of some one class; the

proletariat and the bourgeoisie are together directing the affairs of the

revolution. . . . We must walk together with those forces which participate

in the movement of the revolution and organize the Republic with our forces

in common.' 93

The March revolution brought again into the

forefront all the old social and economic problems which the Tsarist

government had failed to tackle. First and foremost was the agrarian problem.

This, obviously, could not be settled overnight. Accordingly, peasants and

landowners in many parts of Georgia adopted an interim solution, whereby

share-cropping peasants settled on a landowner's estates simply ceased

handing over the master's share of the crop, the so-called gala,

amounting to between one-quarter and one-half of the total. Having no one to

cultivate them on their behalf, the nobility found their domains slipping

from their grasp, while the peasants were now endowed with both their own

former small-holdings and those portions of their former lord's estates which

they had formerly cultivated as share-croppers. Access to communal woodlands

and pastures, monopolized by the landed proprietors under the terms of the

liberation decrees of 1864 onwards, reverted to the peasantry. Plantations,

forests and vineyards owned by members of the former Russian imperial family

were confiscated and nationalized. Small farms belonging to the lesser

squirearchy, a numerous category in Georgian rural society, were relatively

little affected.

Restoration

of the Georgian

Church

Another burning question also swept into

the forefront--that of the autocephaly or independent status of the Georgian

Orthodox Church. As soon as news of the March revolution reached Tbilisi, the Georgian

bishops invaded the headquarters of the Russian exarchate and ejected the

Russian chief bishop and his staff. Georgians were appointed to take their

places and administer the property and estates of the Georgian Church.

The Ozakom was asked to give official sanction to the restoration of the

Georgian patriarchate, abolished by Russia in 1811. However, this

question was simply shelved until the eventual convention of the all-Russian

Constituent Assembly. This did not deter the Georgians from going ahead with

the reorganization of their old national Church. Bishop Kyrion was elected

Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia, taking the title of Kyrion II, and new

statutes were worked out at synods held in Tbilisi in 1917 and at the historic

monastery of Gelati in 1921. Patriarch Kyrion died in 1918, and was succeeded

by Patriarch Leonid, who lived until shortly after the Bolshevik invasion of

1921.

The collapse of the old Tsarist police and

gendarmerie inevitably led in some regions of Georgia to anarchy and unrest.

During the summer of 1917 criminal elements masquerading as revolutionaries

found frequent opportunities for pillage and arson. The Ozakom and the local

Executive Committees set up field courts-martial and a number of terrorists

were shot. Pending the establishment of a regular People's Guard, Zhordania

and his colleagues recruited from Guria a detachment of people's militia

commanded by V. and K. Imnadze, which helped to maintain order where needed.

Belated steps were taken to introduce into Georgia the Russian Zemstvo or

rural district council organization, which had played a leading part in local

government affairs as well as in the liberal reform movement since its

inception during the 1860's. Ilia Chavchavadze and other leading figures in

Georgian public life had for half a century petitioned successive Russian

governors to introduce the Zemstvo pattern of local government into Georgia--a demand regularly rejected by St. Petersburg. Only

now, when the old order was already in dissolution, could this overdue reform

be tried out for a brief season, only to be swept away by the invasion of

Communist Russia in 1921.

From March 1917, then, local authority

within Georgia resided

principally with the Social-Democrats, whose Tbilisi committee, directed by Zhordania

and his deputy Noe Ramishvili, formed the backbone of the Petrograd-appointed

Ozakom. Between the Georgian Social-Democrats and the Kerensky régime in Petrograd there was little basic divergence of aim.

With Nikolai (Karlo) Chkheidze as Chairman of the Petrograd Soviet and Irakli

Tsereteli a prominent minister in the Provisional Government, the Georgian

Mensheviks were able to make their voices heard insistently in the councils

of Russia

and the world. In fact, Trotsky and the Bolsheviks were somewhat afraid of

what they contemptuously termed the 'Georgian Gironde', and accused

Chkheidze, Tsereteli and Zhordania of attempting to dominate and pervert the

Russian revolution and foist upon it their own provincial interests and

ideology.

Disintegration

of Russia's

Caucasian Front

Nevertheless, Tbilisi

and Petrograd were not always in complete

harmony. Divergences often broke out over tactics and priorities. Thus,

Zhordania was strongly critical of the 'democratic cretinism' which inspired

the Kerensky government to postpone settlement of the many crying social and

economic problems left over from Tsardom until these could be referred to a

constituent assembly convened with every refinement of electoral procedure

from all corners of the farflung Russian state. Many of the Tbilisi

Social-Democrats were also opposed, in private at least, to continuance of

the unpopular war with Germany

and Turkey which, it was

manifest, was beyond Russia's

physical resources and presented a serious threat to the future of the

revolution. There was indeed much to be said in favour of a ceasefire on the

Caucasian front, where the Russian army had conquered vast areas of Turkish

Anatolia and Armenia

and was holding out deep in Turkish territory against the depleted and

demoralized remains of the Ottoman Army. Terms advantageous to Russia

could, on this front at least, readily have been obtained. Zhordania later

recalled:

'Preoccupied with these matters, we got

into direct telephone contact with I. Tsereteli and K. Chkheidze at Petrograd. We had discussions with them and acquainted

them with the views of our party and our Soviet. We demanded reforms,

decisive steps towards the conclusion of peace, and so forth. No reply could

we get, except for vague reassurances and appeals for calm: "We are

making preparations, everything will be all right, etc., etc."'94

In the meantime, Russia was moving rapidly towards

the left. Demands for peace at any price resounded through the land, while

Bolshevik agitators urged the peasants to seize the landlords' estates

without awaiting the nebulous deliberations of the Constituent Assembly. By

failing to come to grips with these two fundamental problems--peace and land

reform-the Kerensky government dug its own grave, while Zhordania and his

associates impotently fretted and fumed far away in Tbilisi.

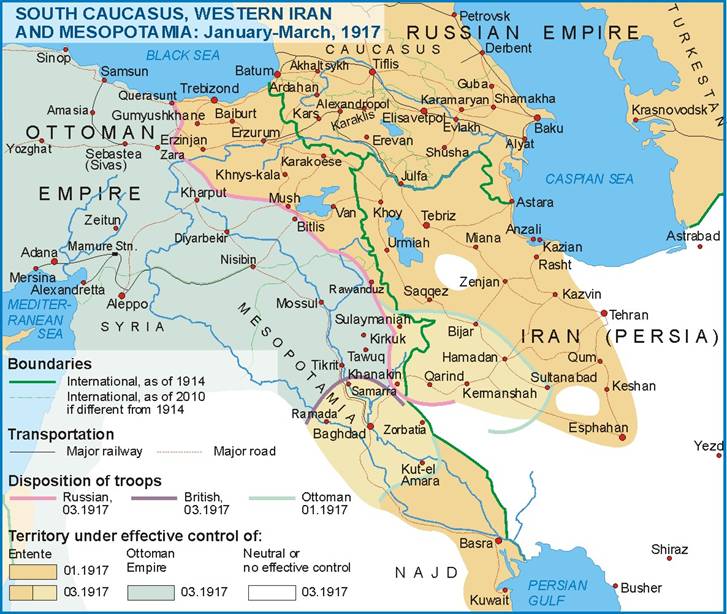

In May 1917, the first congress of

delegates of the Caucasian army met in Tbilisi. It was dominated by the

Mensheviks and the Social-Revolutionaries. There were only a few Bolsheviks

among the delegates, notably Korganov, later Commissar of War in the Baku

Commune, and the Georgian S. Kavtaradze. The Social-Revolutionaries and

Mensheviks professed, in public at least, to believe in the need to continue

the war to a victorious end, whereas the Bolshevik minority unsuccessfully

demanded peace at any price. Whatever the Georgians might have felt, the need

to continue the struggle to the bitter end was irresistibly pressed by the

Armenian Dashnaks and other representatives of the Armenian nation. Mortally

afraid of the Turks, the Armenians had been encouraged by the American

President Wilson to believe that an Allied victory would be followed by the

creation of an independent Greater Armenia carved from the debris of the

Turkish empire and stretching from the Mediterranean to the Caspian

Sea. The Armenians called for complete support of the Petrograd government and the prosecution of war to the

death. And so the war on the Caucasian front was allowed to drag on for many

months more.

Short

rations and Bolshevik broadsheets

As the year 1917 wore on, the situation of Russia's

Caucasian Command became increasingly unfavourable. The majority of the

half-million troops engaged against Turkey were not Georgians or Armenians,

but Russian peasants from the European provinces, whose only concern was to

finish fighting as soon as possible and return home to seize their share of

the estates of dispossessed landlords. Conditions at the front were extremely

harsh. At times, the men of the 4th Caucasian Rifle Division, whose chief of

staff was the Georgian General Kvinitadze, received only half a pound of

bread per day, and horses only one and a half pounds of barley. There was no

meat and no conserves, and the men were boiling soup from the flesh of

donkeys, cats and dogs. Bolshevik newspapers and broadsheets began to

circulate in the ranks, while democratic changes introduced into army

structure by the Provisional Government under pressure from the Workers' and

Soldiers' Soviets rapidly affected discipline and morale. In June 1917, the Russian

commander in the Caucasus, Yudenich,

resigned and was replaced by General Przhevalsky. This change did not improve

the military position. The standstill along the front continued, while there

was a further increase in incidents and disturbances in the rear echelons.

With the October Revolution, demobilization became spontaneous and

irresistible, even before Trotsky began the official negotiations that led to

the peace of Brest-Litovsk.

In the autumn of 1917, the food shortage in

Georgia and Transcaucasia generally became acute. Caucasia had long

depended for a large portion of her wheat and other grain supplies on South Russia. With the general anarchy prevailing in Russia,

these supplies were largely cut off. On 15 October, a special conference on

food supplies was convened in Tbilisi,

attended by the Russian commander on the Caucasian front, General

Przhevalsky. It was estimated that the requirements of the Caucasian Army

amounted to 24 million poods (1 pood = 36 lb.) of flour and 36

million poods of corn, oats and barley annually, while the needs of

the civilian population of Transcaucasia

amounted to another 51 million poods of grain-a total of 111 million poods.

The procurement of such quantities was out of the question. For the civilian

population of Tbilisi,

ten wagon-loads of wheat a day were required, whereas only four were

currently being delivered. A ship which arrived at Batumi

carrying corn from Russia

was commandeered by demobilized soldiers, who sailed back to Russia

in it without unloading the cargo. The bread ration in Georgia was cut still further,

while measures were taken to evacuate town dwellers to country districts.

Schools in Tbilisi

were shut down and the pupils sent off to rural areas. By such measures as

these, the population of the Georgian capital was quickly reduced by some

15,000.

The

Bolsheviks seize power

Early in November 1917, news was received

in Tbilisi of the successful Bolshevik

uprising in Petrograd and the fall of

Kerensky's Provisional Government. The reaction of the Georgian, Armenian and

Azerbaijani Soviets and executive committees was immediate and hostile. On 8

November 1917, the Regional Centre of Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and

Peasants' Deputies met at Tbilisi together with the executive committees of the

Social-Revolutionary and Social-Democratic (Menshevik) parties and resolved

that the interests of the revolution demanded the liquidation of the

Bolshevik insurrection and the immediate convocation of the all-Russian

Constituent Assembly. A few days later, another meeting declared that the war

with Germany and Turkey

should go on and no separate peace be concluded.

The position of the Georgian

Social-Democrats at this juncture was somewhat paradoxical. In their dim,

dogmatic way, they were, no doubt, excellent patriots, though rather

indifferent nationalists, being wholeheartedly devoted to the fashionable

slogans of international brotherhood and workingclass solidarity. Since the

beginning of the century, they had been stumping the country proclaiming Georgia's destiny to help the workers and

peasants of the entire Russian Empire towards economic and political

fulfilment, and combating those who thought that Georgia's

national salvation lay in independence through separation from Russia.

With public speakers of the calibre of Irakli Tsereteli and Nikolai Chkheidze

prominent first in the Tsarist Dumas and then under Kerensky, the Georgian

Mensheviks exerted an influence in Russian affairs out of all proportion to

their numerical strength. The Russian political dog had sometimes been wagged

by its Georgian Menshevik tail. With the triumph of Lenin's Bolsheviks, the

Russian dog had cut itself adrift with a vengeance, while the Georgian tail

was left wagging furiously in a void. Far from rejoicing at their new-found

freedom, the Georgian Mensheviks quailed at the prospect before them. 'A

misfortune has befallen us,' Noe Zhordania lamented. 'The connection with Russia has been broken and Transcaucasia

has been left alone. We have to stand on our own feet and either help

ourselves or perish through anarchy.' 95

Instead of proclaiming Transcaucasia's

independence, as they could readily have done, and coming to terms

immediately with Turkey

and the Central Powers, the Caucasian politicians dallied and played for

time. On 24 November 1917, a conference of the Regional Centre of Soviets,

the Regional Soviet of the Caucasian Army, the Tbilisi City Council, the

Ozakom, the trades unions and other representative bodies met in Tbilisi and decided that since Transcaucasia could not

recognize the Bolshevik usurpation in Petrograd,

a local régime would have to be organized. Since this was regarded as merely

a temporary expedient, pending the suppression of the Bolshevik rebels, the

Georgians continued to make arrangements for the forthcoming elections to the

all-Russian Constituent Assembly. This much-heralded body, it was fondly

believed, would soon quell the unspeakable Bolsheviks and bring Russia

back to the paths of reason and order. In the event, the Constituent

Assembly, in which Lenin's followers were a minority, was forcibly dispersed

by Bolshevik troops after one sitting in January 1918--an event which marked

the deathknell of Russian parliamentary democracy.

The

Transcaucasian Commissariat

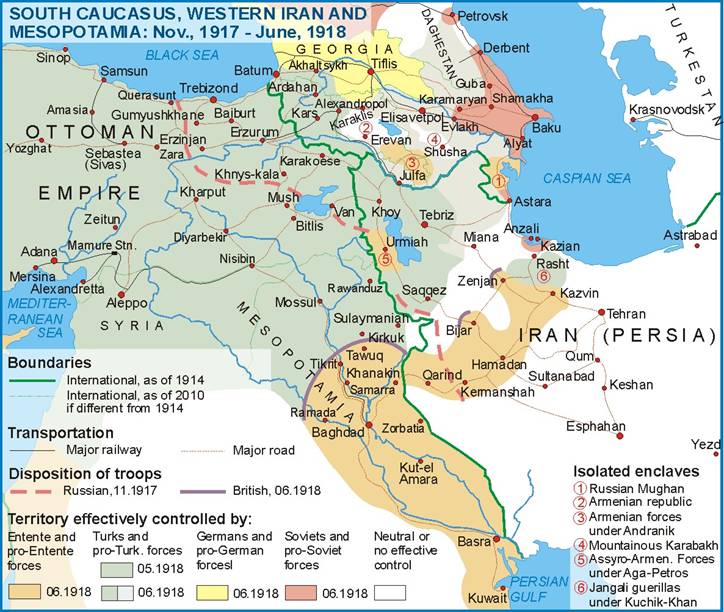

Meanwhile, the Transcaucasian Soviet and

party organizations had set up on 28 November 1917 a provisional government,

called the Transcaucasian Commissariat. It included three Georgians, three

Azerbaijanis, three Armenians and two Russians. The Georgian Menshevik Evgeni

Gegechkori was elected chairman, as well as being Commissar of Labour and

External Affairs. The other two Georgian commissars were Akaki Chkhenkeli

(Interior) and Aleksiev-Meskhiev(Education). While predominantly Menshevik in

character, the commissariat also included nominees of the Muslim Musavat

organization, the Armenian Dashnaks, and the SocialRevolutionaries. The

Bolsheviks were excluded. On the very next day, a detachment of Georgian Red

Guards, recruited from Menshevik workers and led by a former Bolshevik named

Valiko Jugheli, seized the Tbilisi

arsenal, held hitherto by a detachment of Russian soldiers with strong

Bolshevik leanings. Ordered by the Tbilisi Soviet to surrender the place, the

baffled soldiers gave in after a token resistance. In this way the Georgian

capital was preserved from the marauding hordes of Russian troops returning

home pell-mell from the Caucasian front. The capture of the arsenal was a

decisive setback to the Georgian Bolsheviks, and Lenin was extremely

displeased when the news reached him.

While shrinking still from any formal

declaration of independence from Russia, the Transcaucasian

Commissariat entered forthwith into negotiations with the Turks for an

armistice on the crumbling Caucasian front. A provisional agreement between

the Russian General Przhevalsky and the Turkish commander, Vehip Pasha, was

concluded at Erzinjan on 18 December 1917. However, Enver Pasha's Young Turk

government at Istanbul was well aware of the

heaven-sent chance which the Russian revolution offered for Turkey to recover Caucasian territories

wrested from her by Russia

over the preceding century, so that this move was mainly designed to gain

time pending further weakening of Russia's

military and political grip on Caucasia.

Meanwhile, the Russian Bolsheviks were busily negotiating a separate peace

with Germany

and Austro-Hungary at Brest-Litovsk, at which conference, however, the

Caucasian peoples were not directly represented.

The

Turkish menace

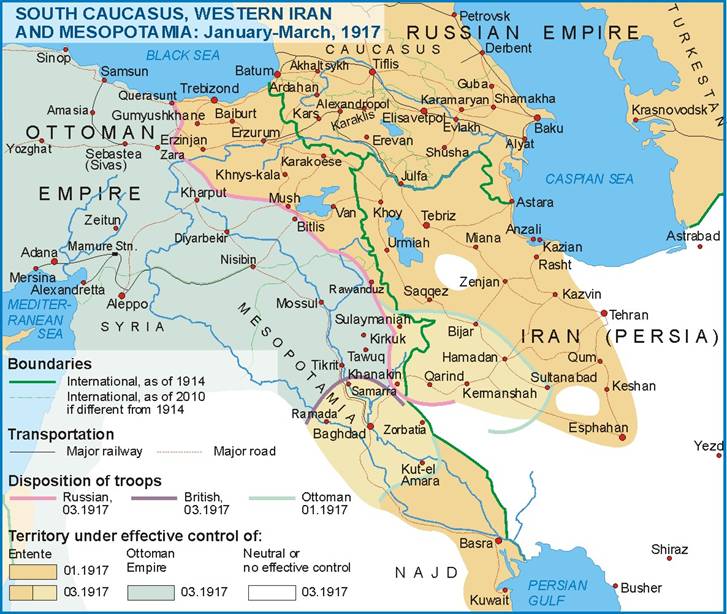

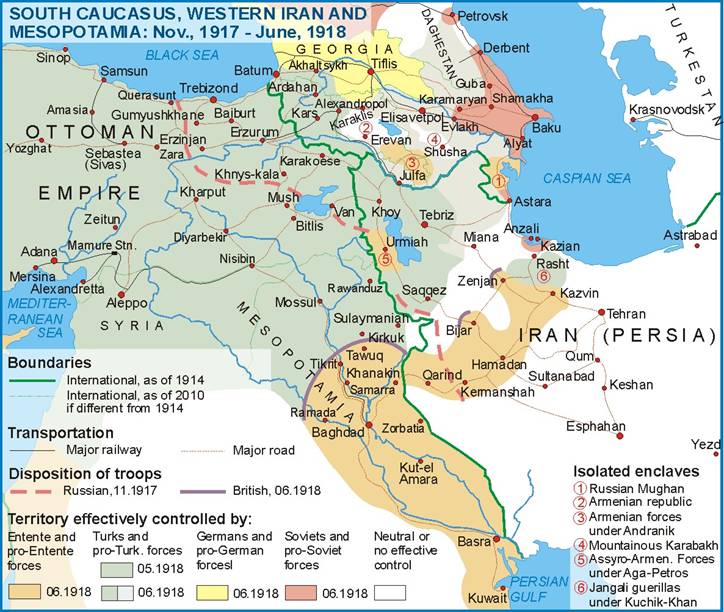

During the winter of 1917-18, the situation

in the Anatolian border areas around the Russo-Turkish front lines deteriorated

still further. Vehip Pasha protested repeatedly to the Russian commander and

the Transcaucasian government about alleged massacres of Turks and other

Muslims by vengeful Armenian guerilla bands. On 12 February 1918 the Turks

broke the truce and advanced against Erzinjan. Before the end of the month,

Erzinjan and Trebizond were once more in

Turkish hands. The Russian Army had by now virtually melted away. Against

Vehip's force of 50,000 men and 160 field guns, the Georgians could muster

only about 10,000 men, of indifferent quality and morale, while the small

Armenian national army, heroic but hopelessly outnumbered, was spread thinly

over a very wide area of difficult and exposed country. The nominal head of

these armies was the Russian general, Lebedinsky, but the real confidence of

the Transcaucasian government was given to the Georgian commander, General I.

Z. Odishelidze, a Knight of the Order of St. George, former Governor of

Samarkand, and late chief of staff of one of the Russian armies on the

European front. Erzurum

was defended by an Armenian garrison under the partisan leader Andronik. The

RussoCaucasian forces were hampered by thousands of panicstricken refugees,

Christian Armenians for the most part, fleeing from the implacable vengeance

of the advancing Turks. There was every prospect that hundreds of thousands

of the Turks and Tatars living in the Caucasus

would rise in support of their triumphant Muslim brethren. Andronik evacuated

Erzurum on 12 March 1918, while Batumi, Ispir, Kars

and Van were menaced by the Turkish spearheads.

In the meantime, Trotsky had signed the

Treaty of BrestLitovsk, whereby the Bolsheviks agreed to exclude from Russian

territory the districts of Batumi, Ardahan and Kars, where the fate of the

population was to be decided by a free plebiscite. In prevailing conditions,

this meant abandoning the Armenian and Georgian Christian inhabitants to the

mercy of the Turks.

A peace conference between representatives

of Turkey and

Transcaucasia opened at Trebizond on 14

March 1918. Vehip Pasha immediately demanded the evacuation of all districts

abandoned by Russia

at Brest-Litovsk. The Transcaucasian delegates, led by the Georgian

politician Akaki Chkhenkeli, protested that they did not recognize

Brest-Litovsk and were not bound by its conditions. Prolonged parleys took

place until the Turks, flushed with victory, delivered an ultimatum demanding

the evacuation of the disputed districts not later than 10 April 1918.

Brest-Litovsk

repudiated

The Turkish ultimatum was received with the

greatest indignation in the Transcaucasian Diet or Seim. This new

parliamentary body, which assembled at Tbilisi

on 23 February 1918, was a local substitute for the short-lived Russian

Constituent Assembly in Petrograd which had

been so unceremoniously dispersed by Lenin's Bolsheviks. Nikolai Chkheidze

and Irakli Tsereteli, dethroned from their tribunes in the Petrograd Soviet

and Provisional Government, now reappeared in their native Georgia to raise the clarion call

of revolutionary democracy. A tug-of-war ensued between the Transcaucasian

delegation at the Trebizond peace conference and the government and Diet in Tbilisi. On 10 April

1918, Chkhenkeli declared himself willing to accept the Brest-Litovsk treaty

and conduct further negotiations based upon it. Simultaneously, Tbilisi was gripped by

patriotic and warlike frenzy. On 13 April 1918, Irakli Tsereteli declared in

the Diet: 'Turkish imperialism has issued an ultimatum to Transcaucasian

democracy to recognize the treaty of Brest-Litovsk. We know of no such

treaty. We know that in Brest-Litovsk the death sentence was passed upon

Revolutionary Russia, and that death sentence to our fatherland we will never

sign!' Tsereteli's speech was greeted with thunderous applause. The next day,

Evgeni Gegechkori, the Transcaucasian Premier, telegraphed Chkhenkeli and

told him to break off negotiations with the Turks and leave Trebizond.

That night, despite the manifest reluctance of the Muslim representatives,

the Transcaucasian Diet declared war on the Turks.

This bellicose act was a piece of somewhat

ridiculous panache. Divided against itself, Transcaucasia

had neither the means nor, in so far as the Muslim elements were concerned,

the will to resist. On 15 April 1918, it was announced in Istanbul

that the Turkish Army had entered Batumi.

Some of the forts had surrendered without firing a shot and the town and port

had been occupied without resistance. The Muslim Georgians of Lazistan and of

Atchara, of which Batumi is the main city, were helping the Turks, tearing up

railway lines, wrecking trains and conducting guerilla operations generally.

Having now seized most of the territories they coveted, the Turks renewed

their peace overtures. On 22 April 1918, Vehip Pasha telegraphed Chkhenkeli

and asked whether he was now prepared to resume peace talks. The

Transcaucasian Diet had no alternative but to accept the offer.

An

ephemeral federation

For the last six months, the Transcaucasian

Commissariat had clung to the illusion that Russia

would soon quell the Bolshevik usurpers and revert to the paths of true

democracy, in which case Transcaucasia would

be painlessly restored to the broad bosom of Russian Social-Democracy. While

refusing to recognize the surrender at Brest-Litovsk, these half-hearted

patriots delayed taking the only step which could preserve their country from

complete ruin--namely a declaration of complete independence from Russia,

combined with a real effort to enlist the support of interested foreign

powers against the Turkish peril. At the end of March 1918 the question of

Transcaucasian independence was discussed in the Diet, which voted

'categorically and irrevocably' against independence. On 22 April another

lengthy debate on this issue took place, as a result of which the majority of

the assembly adopted the motion 'that the Transcaucasian Seim decide to

proclaim Transcaucasia an independent

Democratic Federative Republic'. The formation of a cabinet was entrusted to

the Georgian Chkhenkeli.

On 26 April 1918, Chkhenkeli, who combined

the offices of Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary, published the names of

the members of his new Transcaucasian Ministry, which contained four

Georgians (including Chkhenkeli himself), five Armenians and four Azerbaijani

Muslims. The other Georgian ministers were Noe Ramishvili (Minister of the

Interior), G. Giorgadze (Minister of War) and Noe Khomeriki (Minister of

Agriculture). When presenting his cabinet to the Diet, Chkhenkeli made a

speech in which he outlined his government's programme, which featured the

writing of a constitution, the delineation of the new state's frontiers, the

liquidation of the war with Turkey, the combating of both counter-revolution

and anarchy, and finally, the carrying through of land reform. On 28 April

1918, the newly created Democratic Federative Republic of Transcaucasia was

recognized by the Ottoman Empire.

The Federative Republic,

born under such unfavourable auspices, lived but one brief month. Three days

after its formation, the Turks occupied the great fortress of Kars, from which

thousands of panic-stricken men and women streamed out, carrying their

children and their possessions on their backs. Those who were too old or too

sick to walk were left to the mercies of the Turk. Food shortages were

producing famine in many regions of Caucasia, notably in Armenia and Azerbaijan. Another disruptive

factor was the situation in the great oil port of Baku

on the Caspian, which was a Bolshevik stronghold within otherwise Menshevik

Transcaucasia. In December 1917, Lenin had appointed the Armenian Bolshevik

Stepan Shaumian as Commissar Extraordinary of the Caucasus.

Shaumian was chairman of the Baku Soviet, in which he was backed by the well

known Georgian Bolshevik Prokopi (Alesha) Japaridze. In March 1918, the Baku

Soviet was involved in open conflict with the Azerbaijani nationalist

organization, the Musavat. This led to inter-communal fighting between the

Baku Armenians and Tatars, lasting for several weeks, and resulting in

wholesale massacre of innocent victims. When the streets had been cleared of

thousands of dead bodies and the fires extinguished, the Bolsheviks emerged

as the strongest force in the city. On 25 April 1918, a local Council of

People's Commissars, modelled on the one in Moscow, was formed under Shaumian's

chairmanship. Spurning all allegiance to the Menshevik régime in Tbilisi, the Baku Bolsheviks nationalized the vast

oilfields around their city and placed them at the disposal of the Moscow government, from

which they derived constant moral support.

The resumed peace talks between Turkey and Transcaucasia opened at Batumi, now in Turkish

hands, on 11 May 1918. The Transcaucasian delegation, forty-five strong, was

headed by Premier Chkhenkeli, and also included the veteran Georgian

revolutionary and publicist Niko Nikoladze, and the jurist Zurab Avalishvili.

Vehip Pasha stated that the old peace conditions no longer applied, since the

Armenians and Georgians had responded to the earlier Turkish proposals by

armed resistance. Vehip now demanded the cession of the Georgian regions of

Akhaltsikhe and Akhalkalaki and the Armenian district of Aleksandropol by the

Turks of all Transcaucasian railways so long as the war against Great Britain

continued. In view of the impossibility of armed resistance, there seemed

nothing to prevent the Turks from establishing complete hegemony over the

Caucasian isthmus.

German

takes a hand

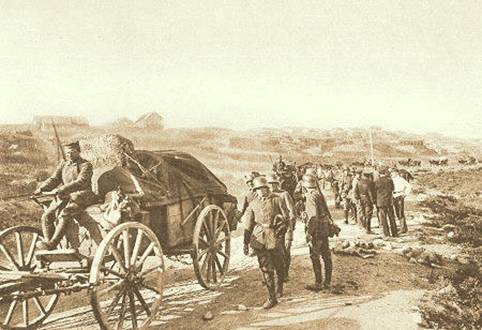

The Turks had reckoned without one very

important factor, namely the intervention of their ally Imperial Germany,

which at this time dominated the Ukraine

and the Crimea and had virtually turned the Black Sea

into a German lake. The Germans were in urgent need of the oil of Baku and had no desire to see the entire Middle East,

and perhaps Central Asia too, fall into the

hands of their ambitious Turkish friends. Thus it was that a strong and alert

German delegation also attended the Batumi

conference. Headed by the Bavarian general von Lossow, it also included Count

von der Schulenburg, a former German Consul in Tbilisi,

Arthur Leist, famous as a translator and scholar of Georgian literature, and

O. von Wesendonk, later Consul-General in Tbilisi and author of studies on Georgian

history and civilization. Von Lossow proffered his services as mediator

between the Turks and the Transcaucasians. He also sent to Tbilisi Colonel

Kress von Kressenstein, who entered into close touch with the Georgian

members of the Transcaucasian government and started collecting together a

special German task force from prisoners of war, peasants from the German

settlements around Tbilisi,

and any other German nationals whom he could assemble. Since the Georgians

and Armenians regarded the Germans as among the highest representatives of

European culture, science and technology, they were delighted at the sudden

prospect of this excellent barrier which would halt Turkey's onward advance. At

railway stations and other strategic points German helmets were soon to be

seen, which the Christian inhabitants thought vastly preferable to the

Turkish fez.

|

|

|

|

Otto

von Lossow

|

Friedrich

Freiherr Kress von Kressenstrin

|

|

Germans

on their way to Tiflis

Germans in

Tbilisi

|

Captain Egon Krieger: Head of German military mission in Georgia

Birth

of the Georgian

Republic

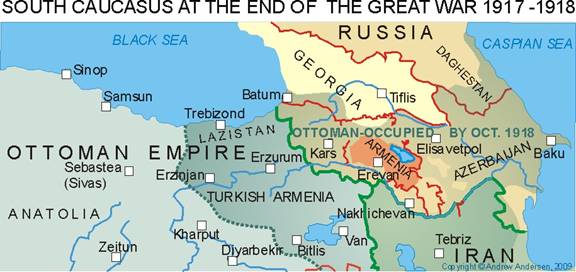

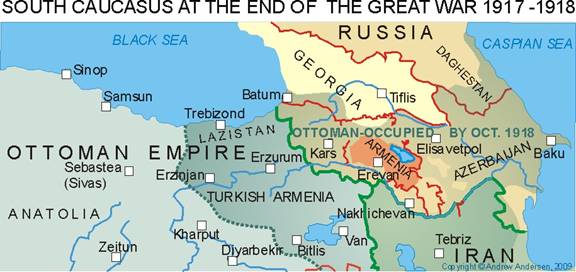

There was no time to lose, if anything was to

be salvaged from the wreck of united Transcaucasia.

The Azerbaijani Muslims, who had nothing to lose by a complete Turkish

victory, were opposed to further resistance. The Armenians, for all their

heroism, were exhausted and incapable of organized action. Each of the

Caucasian nations had to look to its own corporate survival. As soon as this

became evident, Noe Zhordania, leader of the Georgian Social-Democrats and

President of the Georgian National Council in Tbilisi,

was summoned to Batumi.

There he concerted measures with the Georgian delegation at the peace

conference and then returned to Tbilisi with

the necessary authority to proclaim Georgia an independent republic

and to bring about the final dissolution of the Transcaucasian Diet. On 24

May 1918, von Lossow announced that owing to Turkish intransigence, his

efforts at mediation had failed, and that the German delegation would leave Batumi at once on the

S.S. Minna Horn. Two days later, the Transcaucasian delegation received a

Turkish ultimatum, demanding the acceptance of all Turkish proposals within

seventy-two hours, including the cession to Turkey of vast tracts of Georgian

territory. But the Turks had been outwitted. That same day, 26 May 1918,

Irakli Tsereteli in the Diet in Tbilisi had proclaimed Georgia a sovereign

country independent of the Transcaucasian Federative Republic, which was now

dissolved; Zhordania read a formal Act of Independence; and von Kressenstein

and von der Schulenburg appeared in person at the Tbilisi Town Hall, to announce

the establishment of a German protectorate over the newly born Georgian

republic.

The first Prime Minister of the Georgian Republic was Noe Ramishvili, while

Akaki Chkhenkeli received the portfolio of Foreign Affairs. These two new

ministers immediately hurried to the Black Sea port of Poti,

where von Lossow and his German colleagues were waiting impatiently on board

their steamer. A provisional agreement between Imperial Germany and the Georgian Republic was signed at Poti on 28 May

1918. this convention provided among other things for Germany to have free

and unrestricted use of Georgia's railway system and all ships found in

Georgian ports, for the occupation of strategic points by German troops, the

free circulation of German money in Georgia, the establishment of a

German-Georgian mining corporation, and the exchange of diplomatic and

consular representatives. Von Lossow also sent a secret letter to the

Georgian government, pledging his good offices towards securing international

recognition for the Georgian republic and safeguarding her territorial

integrity. Thereupon, von Lossow and his suite set off across the Black Sea

to Constanza, taking with them a Georgian delegation composed of Chkhenkeli,

Avalishvili and Nikoladze, who were sent on to Berlin to enter into formal

discussions with the Kaiser's government and the officials of the

Wilhelmstrasse. Lengthy negotiations between the Georgians and the German

Foreign Ministry ensued, only to be rendered abortive by the defeat of

Imperial Germany at the hands of the Allies in November 1918.

Back in Batumi,

a peace treaty between Turkey

and Georgia was signed on

4 June 1918, whereby Turkey

regained Batumi, Ardahan and Kars, as well as Akhaltsikhe and

Akhalkalaki. However, the main treaty of peace and friendship between Georgia and Turkey was never formally

ratified. True to their policy of playing off the Turks and Germans against

one another, the Georgian delegation in Berlin declared to the German Foreign

Ministry that 'inasmuch as Georgia, under direct pressure from Turkey, was

compelled to sign any agreement whatsoever with her alone, the obligations

incurred in such conditions must be considered null and void'. An attempt by

Turkish troops to take possession of certain border areas of Georgia allegedly ceded to Turkey by the treaty of 4 June

was repulsed by Georgian and German troops acting in concert, provoking a

regular crisis between the German and Turkish governments. On 20 June 1918, a

Georgian delegation headed by Evgeni Gegechkori arrived at Istanbul

to take part in a general conference to revise the treaties of Batumi. Before anything

had been settled, military defeat brought the Ottoman

Empire itself tumbling down in ruin. By the end of 1918, as we

shall see, German and Turkish hegemony over Caucasia

had melted away, to be replaced for a short season by the rather less popular

occupation of the victorious British.

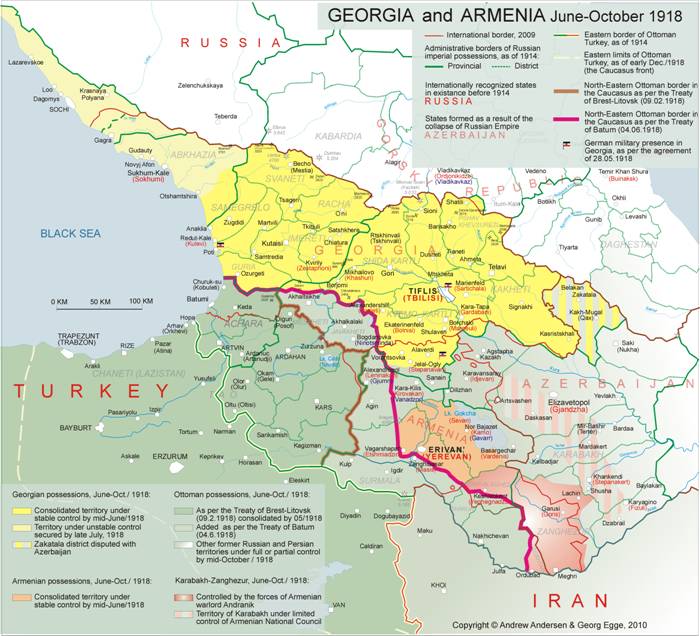

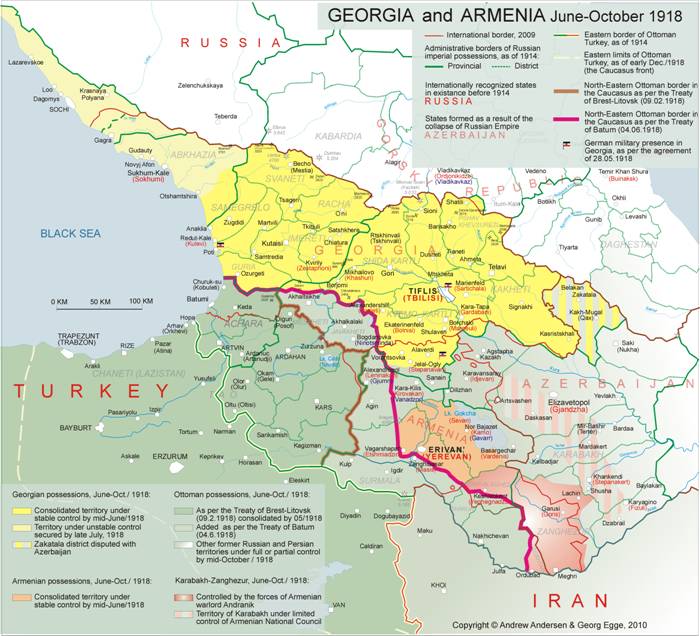

Click

on the map for better resolution

Click here to continue

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

92. F.

Kazemzadeh, The Struggle for Transcaucasia, 1917-1921, New York, Oxford

1951, p. 34.

93. Quoted

by Kazemzadeh, The Struggle for Transcaucasia,

p. 37.

94. N.

Zhordania, Reminiscences, p. 113.

95. Quoted

by Kazemzadeh, The Struggle for Transcaucasia,

p. 55.

|

|