|

|

GEORGIA UNDER THE TSARS:

RESISTANCE, REVOLT, PACIFICATION: 1801-32

The liquidation of the old order--Prince Tsitsianov--Death of a general--Subjugation of Western

Georgia--KingSolomon II and Napoleon Bonaparte--The

revolt of 1812--Suppression of the Georgian Church--Economic progress and

literary contacts--The conspiracy of 1832

The

liquidation of the old order

WHEN TSAR ALEXANDER I published his

manifesto of 12 September 1801, declaring the East Georgian kingdom of Kartlo-Kakheti irrevocably joined to the Russian empire,

he also made public the outline of a new system of administration for the

country. The land was now divided into five districts or uezdy

on the Russian model, three in Kartli and two in Kakheti, with administrative centres at Tbilisi, Gori, Dusheti, Telavi and Sighnaghi. With the Georgian royal family removed from

power, the commander-in-chief on Russia's

Caucasian front was now supreme head of the central government at Tbilisi by virtue of proconsular powers conferred on him by the Tsar.

Authority on the spot was vested in a council of Russian and Georgian

officials headed by the commander in chief's deputy, who received the title

of pravitel or administrator of Georgia.

The administration was divided into four branches or 'expeditions'--the

executive, the financial, and the criminal and civil judiciaries. Each branch

was to be headed by a Russian official set over four Georgian committee

members. Corresponding local administrations were to be set up in the country

districts under Russian kapitan-ispravniki

or district officers. The mountain clans of the Pshavs,

Khevsurs and Tush, as

well as the Tatar nomads dwelling in the southern borderlands, continued to

be governed by Georgian mouravs or prefects.

For civil litigation, the code of King Vakhtang VI

remained in force, while criminal cases were to be judged according to

Russian law.

The high-handed way in which Alexander had

suppressed the independence of Kartlo-Kakheti did

not pass without protest. The late King Giorgi's

second son, Ioane, who had come to St. Petersburg, tried to

organize a nation-wide petition to be submitted to the emperor, urging him at

least to maintain the royal title in the Bagratid

line in accordance with the treaty of 1783 and subsequent Russian pledges. Ioane's correspondence was seized by the Russian

authorities, and his efforts frustrated. The Georgian envoys who had been

sent to St. Petersburg by King Giorgi to negotiate an extension of Russian suzerainty

over Georgia

protested vigorously at the fashion in which the Russians had devoured their

country, without any pretence of negotiation, and without even notifying the

Georgian delegation of what was afoot. A number of petitions were received

from Georgia,

urging the claims of the Prince-Regent David or of his uncle, Prince Yulon, to be retained as titular head of the Georgian

administration. It appears also that representatives of Western powers

expressed, albeit discreetly, their misgivings at the way in which Georgia's

absorption had been effected. But the Tsar stuck to his decision, and refused

to make any concession to the Georgians' national pride and susceptibilities.

On 12 April 1802, the Russian

commander-in-chief in the Caucasus, General Karl Knorring,

published in Tbilisi

the imperial proclamation of September 1801, confirming Tsar Paul's earlier

decree, and affirming Kartlo-Kakheti to be an

integral part of the Russian dominions. The general then administered to the

princes and notables of Georgia

the oath of allegiance to the Tsar. The effect was somewhat marred by the

presence of armed Russian guards around the audience hall, making it clear

that any attempt to avoid due compliance would provoke reprisals. A few

Georgians who voiced disapproval were taken into custody. This made a poor

impression on Russia's

new subjects, deemed to have placed themselves voluntarily under the Tsar's

benevolent protection.

General Karl Knorring

The new Russian administration was set up

in Tbilisi in

May 1802. The administrator of Georgia was a certain Kovalensky, who had served as Russian envoy at the

Georgian court during the reign of the late King Giorgi

XII. This Kovalensky had already made himself obnoxious to the Georgians by his haughty manner

and bullying demeanour. They were not reassured to see him back among them,

invested with all the authority of the Russian state.

During these first two years of Russian

rule, the internal situation in Eastern Georgia

left much to be desired. Russian authority was confined to only a small part

of Transcaucasia, namely the area centred on Tbilisi, measuring about one hundred and

ninety miles long by one hundred and forty miles wide. This bridgehead of

Russian power was ringed about by Persian khans, Turkish pashas, wild

mountaineers, and unsubdued Georgian princelings, most of them hostile to Russia. Marauding parties of Lezghis on their agile steeds roamed the countryside,

defying the less mobile Russian garrisons. The Ossetes who dominated the Daryal

Pass, Russia's only supply line over the Caucasus

range, held up travellers and convoys. Trade was virtually at a standstill,

while the peasantry scarcely ventured out to plough the fields.

The widow of King Erekle

II, the redoubtable Dowager Queen Darejan,

continued to intrigue in favour of her eldest son, Prince Yulon,

whom she wished to see installed as king under the Russian aegis. The nobles

and people, while affirming their desire to remain under Russian protection,

continually agitated for a prince of their own. The Russian authorities

interpreted this natural aspiration as insurrection, and made a number of

arrests. Seeing scant improvement in the state of the country, the Georgians

lost faith in the Russian government and its local representatives.

Prince Tsitsianov

The chief administrator in Tbilisi, Kovalensky, was not the man to restore general

confidence. He was busy enriching himself by disreputable speculations in the

bazaar, and allotting key positions in the government to his relatives and

friends. The Georgian councillors whose appointment

was provided for in the manifesto of September 1801, were never nominated.

Corruption and abuse went unchecked. Official documents of the time show that

rape and acts of violence were commonly committed by Russian officials and

soldiery. Prince Tsitsianov, who later succeeded Knorring as commander-in-chief, alludes in one of his

reports to the 'crying abuses of authority committed by the former

administrator of Georgia',

which had 'gone beyond the Georgian people's limits of patience'. Even the

official Russian historian of the Caucasus,

A. P. Berzhe, remarks that 'Kovalensky

and Company did not remove, but aggravated the abuses from which the Georgian

people so grievously suffered. . . . Disappointed hope for improvement turned

into ill-will, discontent, and impotent resentment, in fact the very impulses

from which derive rebellion and revolt against supreme authority.'20

Rumours of Kovalensky's

nefarious activities soon reached St.

Petersburg. It was reported to the Tsar by one of

his trusted advisers, Count Kochubey, that Knorring and Kovalensky 'were

committing great exactions; that they were maintaining discord among the

peoples of the country in order to be able to pillage them with more ease;

and all kinds of similar horrors'.

It can hardly be said that Tsar Alexander

was much of a liberal in his dealings with his Georgian subjects. But he was

determined at least to keep up appearances, and saw how much Georgia needed a governor with courage and

integrity, and some direct knowledge of local conditions and of the mentality

and culture of Russia's

new citizens.

Prince Pavel

Dmitrievich Tsitsianov (Pavle Tsitsishvili)

Fortunately, so it seemed, the ideal man

was to hand in the person of Prince P. D. Tsitsianov,

a scion of the Georgian noble family of Tsitsishvili.

Tsitsianov was an officer with a distinguished

record in the Russian Army; he had been a disciple of the illustrious

Suvorov. He was also a distant relative of the widow of King Giorgi XII of Georgia, Queen Mariam,

who had been a Princess Tsitsishvili. In September

1802, Alexander appointed Tsitsianov

commander-in-chief on the Caucasian Line, with viceregal

powers over Georgia.

He was instructed to introduce order and prosperity into the country, and to

show the Georgian people that 'it would never have cause to repent of having

entrusted its destiny to Russia'.

The Tsar further empowered him to take immediate steps to persuade--if

necessary by physical force--the former Georgian royal family to settle in Russia,

and thus put an end to all agitation for the Bagratid

dynasty to be retored.

Arriving at Tbilisi on 1 February 1803, Tsitsianov's first care was to pack off the remaining

members of the old royal family. The former Prince-Regent David and his

uncle, Prince Vakhtang, left Tbilisi under escort later in February.

There remained the Dowager Queen Darejan, widow of Erekle II, and the widow of the late King Giorgi XII, Queen Mariam, with

her seven children. In April, Tsitsianov heard that

Queen Mariam was planning to flee to the mountain

strongholds of Khevsureti with the aid of loyal

clansmen from the hills. He therefore gave orders that the queen and her

children should be sent off into exile in Russia under guard the very next

morning. To impart an air of ceremony to the proceedings, it was decided that

Major-General Lazarev, commander of Russian troops

in Tbilisi,

should proceed in full uniform to the queen's residence, with a military band

and two companies of infantry, and prevail upon her to take her departure

forthwith.

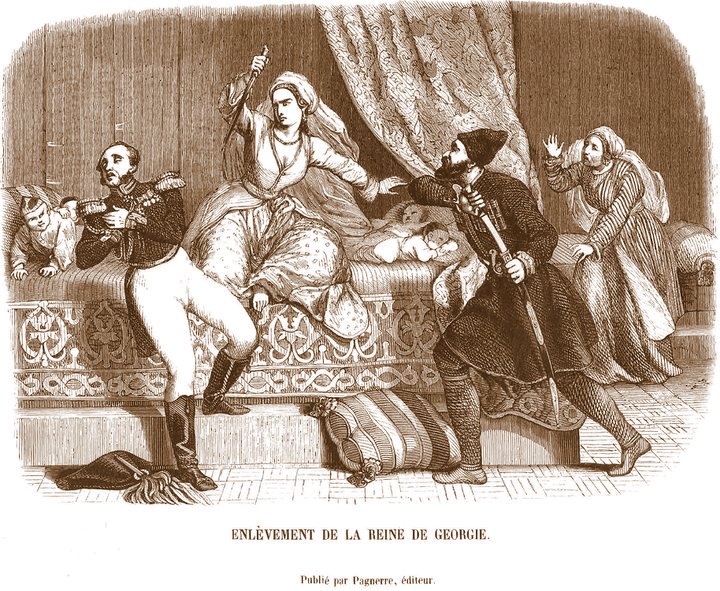

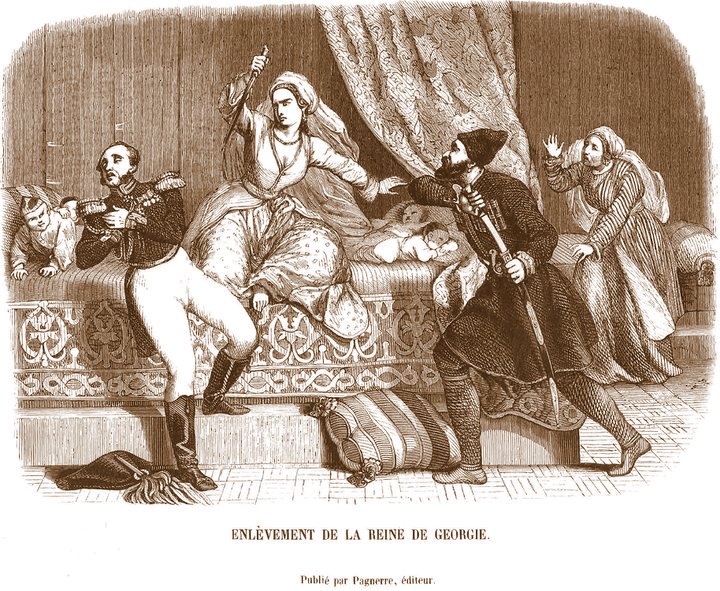

Death

of a general

Of the ensuing tragedy there are several

contemporary accounts, based on the reports of eye-witnesses. 21 Arriving

at Queen Mariam's mansion, Lazarev

found her in her private apartment, seated on a couch, and surrounded by her

seven sleeping children. The general strode brusquely up to the queen and

said, through his interpreter: 'Get up, it is time

to be off.'

The queen calmly replied: 'Why this hurry to get up? Can you not see my children

peacefully asleep round about me? If I wake them up abruptly it might be

harmful to them. Who has given you so peremptory an order?'

The general replied that his orders were

from Prince Tsitsianov himself.

' Tsitsianov--that mad dog!' Queen Mariam

cried out.

At this, Lazarev

bent down to drag her forcibly to her feet. The queen was holding on her

knees a pillow, beneath which she held concealed the dagger which had

belonged to her late husband, King Giorgi. As quick

as lightning, she drew the dagger and stabbed Lazarev

through the body with such force that the tip of the weapon emerged through

his left side. Mariam pulled the dagger from the

gaping wound and threw it in the face of her prostrate tormentor, saying: 'So

dies anyone who dares add dishonour to my

misfortune!'

At Lazarev's

expiring cry, his interpreter drew his sword and hacked at the queen's left

arm. Soldiers rushed in and beat at the queen with their rifle butts. They

dragged her from the house all covered in blood, and hurled her with her

children into a carriage. Escorted by a heavy guard of armed horsemen, the

party left Tbilisi along the military road

leading to Russia over the

Daryal

Pass. Everywhere the queen's

carriage was surrounded by devoted Georgians, who wept as they struggled to

bid farewell to the family of their late sovereign. These loyal

manifestations were repulsed by the Russian soldiery.

When one of the children cried out that he was thirsty, a bystander brought

up a jug of water, which the Russian escort hurled to the ground. On arrival

in Russia, Queen Mariam was imprisoned for seven years in a convent at Voronezh. She lived to a

great age, and eventually died at Moscow

in 1850. She was interred at Tbilisi

with regal honours.

The Queen Dowager Darejan--'that

Hydra', as Tsitsianov delicately termed her--held

out until the October of 1803, when she too was bundled off to Russia.

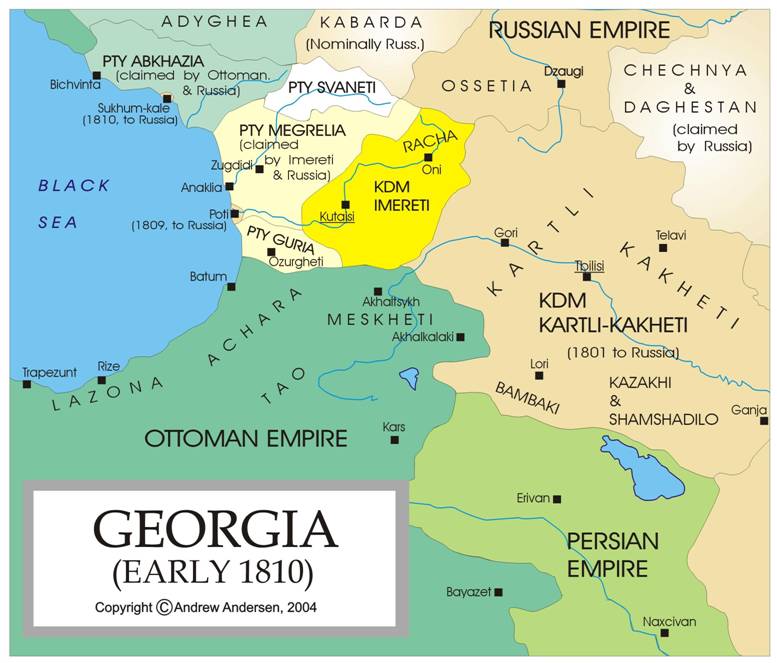

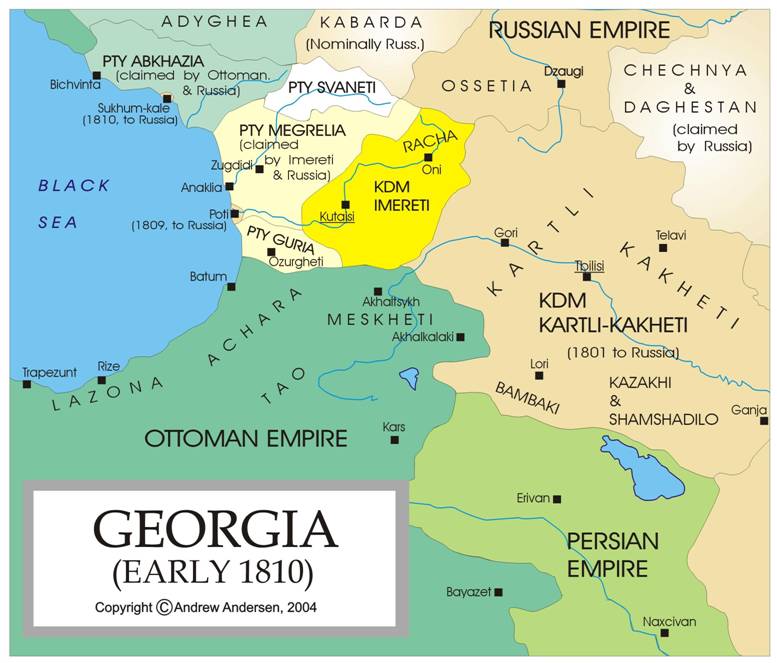

Click on the map for better

resolution

Subjugation of Western

Georgia

Having eliminated these obstacles, Tsitsianov rapidly extended Russia's

grasp on Transcaucasia. He saw the urgency

of securing as rapidly as possible the entire area between the Black Sea and the Caspian. From his headquarters in Tbilisi, he turned his

attention westwards to Imereti. Western

Georgia was at this time torn by a feud between King Solomon II

of Imereti and his nominal vassal, the

semi-independent prince-regent or Dadian Grigol of Mingrelia. One of Grigol Dadian's predecessors

had sworn fealty to the Tsar of Russia as long ago as 1638. Now, in 1803, his

country was taken under direct Russian suzerainty. In contrast to the

situation in Eastern Georgia, the local

administration was left to the princely house, which retained control under

nominal Russian supervision until the dignity of Dadian

was finally abolished in 1867. With his principal vassal and foe now under

Russian protection, King Solomon of Imereti felt it

wise to feign submission. His dominions also were in 1804 placed beneath the

imperial aegis, under guarantees similar to those given to the Dadian. However, Solomon remained at heart bitterly opposed

to his foreign overlords, and his court at Kutaisi was a hot-bed of anti-Russian

intrigue.

Eastwards of Tbilisi,

Georgia's internal

security was still threatened by the warlike Lezghian

tribesmen of Daghestan, and by the independent

Muslim khans of Ganja, Shekki

and Baku,

allies and nominally vassals of the Shah of Persia. Tsitsianov

sent several expeditions against the Lezghis, with

only partial success. His bravest lieutenant, General Gulyakov,

was killed in one of the bloodthirsty engagements which took place. In his

dealings with the Muslim potentates of Daghestan, Tsitsianov did not mince words. 'Shameless sultan with

the soul of a Persian--so you still dare to write to me! Yours is the soul of

a dog and the understanding of an ass, yet you think to deceive me with your

specious phrases. Know that until you become a loyal vassal of my Emperor I

shall only long to wash my boots in your blood.' 22 With

language of this kind, backed by cold steel, Tsitsianov

eventually abated the Lezghian menace and improved Georgia's

internal security.

On 3 January 1804, Prince Tsitsianov took the important trading centre and fortress

of Ganja by storm. Its ruler, Javat

Khan, had been a bitter enemy of the Georgian kings, and had helped Agha Muhammad Khan Qajar to

invade Georgia and sack Tbilisi in 1795. Javat was now slain on his own battlements. The town was

renamed Elizavetpol, in honour of the Empress

Elizabeth, consort of Alexander I. (It is the presentday

Kirovabad.)

This success enhanced Russian prestige to such an extent that for the time

being, to use the historian Dubrovin's metaphor,

the rulers of neighbouring, khanates took on a demeanour of lamb-like

meekness. 23

During the reign of King Erekle II, the rulers of both Ganja

and the chief city of Armenia, Erivan, had been vassals of the Georgian crown. Having

subjugated Ganja, Tsitsianov

judged the moment ripe for an expedition to Erivan.

He learnt also that the Persians were massing a large army in Azerbaijan to the south, in preparation for an

onslaught on the Russian dominions in the Caucasus.

Determined to nip this in the bud, Tsitsianov

marched against Erivan in June 1804,

defeated a Persian force under the Crown Prince, ' Abbas

Mirza, and laid siege to the city. A wet autumn,

supply difficulties, and skirmishing attacks by the Persian light cavalry,

ultimately forced Tsitsianov to raise the siege and

retire to Tbilisi.

A contributory cause of this fiasco was a

mass uprising which broke out along the Georgian military highway over the Caucasus range, on which the Russians depended for all

reinforcements and supplies. This was the first of several spontaneous mass revolts

against Russian rule. Its unmistakably popular character distinguished it

from earlier movements of protest headed by the Georgian royal house and

landed aristocracy.

The immediate reason for the outbreak was

the severity of the Russian commandants in the Daryal Pass and Ananuri

sectors. The Ossete mountaineers and the villagers

of Mtiuleti were forced to toil without payment on

the roads and were mercilessly flogged, some dying from their injuries.

Others perished from cold in clearing away snow drifts. The peasants broke

into revolt and killed the town commandant of Ananuri.

The insurgents were joined by contingents of the Khevsurs

and other mountain clans. They received encouraging messages from Prince Yulon, who still hoped to win the Georgian throne, and

from the Shah of Persia. The rebels defeated a regiment of Don Cossacks sent

from the North Caucasian Line, cut communications between Georgia and Russia,

and menaced the town of Gori. The onset of autumn and

the arrival of Russian reinforcements strengthened Tsitsianov's

hand. The insurgents were no match for regular troops, and the revolt was

brought under control. Reprisals followed and whole families were shut up in Gori castle and left to perish of hunger and cold.

Despite these difficulties, Tsitsianov did his best

to put the social and economic life of Georgia on a sound footing. It

had been one of the conditions of the various pacts concluded between Russia and Georgia that the Georgian

aristocracy and squirearchy should be confirmed in

their traditional privileges, and placed on the same footing as the Russian

nobility. Feudalism as practised in Georgia

was by no means identical with the Russian system of serf proprietorship,

which had reached the high point

of its development during the reign of Catherine the Great, and was in many

ways indistinguishable from outright slavery. However, Tsitsianov

did the best he could to regularise relationships between the Georgian nobles

and their vassals, though many grievances and misunderstandings arose under

the new dispensation.

Tsitsianov was well aware of

the urgency of improving trade and communications, with a view to feeding the

Russian garrisons off the land and clothing them from local resources,

increasing the customs and excise revenues, and generally making the country

self-supporting. The town bourgeoisie were afforded special protection, with

inducements to expand their operations. For some years to come, however, the

occupation of Georgia

entailed a substantial drain on the central Russian treasury. In 1811, for

instance, a million silver rubles had to be sent to

pay the troops and civil servants stationed in the country.

Education and public amenities were not

neglected. Prince Tsitsianov founded a school in Tbilisi for sons of the

aristocracy. Special scholarships, notably in medicine, were founded to

enable some students to continue their studies at Moscow University.

The Georgian printing press which had functioned in Tbilisi until Agha

Muhammad Khan destroyed it was now reinstalled. A State-owned apothecary's

shop was opened, as well as a botanical garden, since famous throughout Russia.

In 1804, a mint was opened in Tbilisi, at

which a distinctive Georgian silver and copper coinage was struck until 1834,

when the standard Russian coinage was given exclusive currency in Georgia.

Public buildings constructed on European lines began to make their appearance

in the Georgian capital, while the citizens were encouraged to rebuild those

quarters of the town which had been completely laid waste by the Persians in

1795.

With his Georgian ancestry, Tsitsianov fully realized the dangers inherent in

over-hasty russification of Georgia's administrative and

judicial system. He recommended that the transition from the old oral system

of administering justice to the bureaucratic formalism characteristic of

Russian official procedure should be brought about by gradual stages. He

thought that it would be best to retain the Georgian language as the medium

for transacting local official business. However, Tsitsianov

set his face firmly against any concession to Georgian national sentiment.

Loyalty to the Russian Tsar and his own personal ambition overrode any regard

which he might have had for Georgia's

glorious past and for her ancient dynasty, the Bagratids.

Thus when Count Kochubey, Alexander's

liberal-minded minister of the interior, wrote in 1804 to ask whether one of

the Georgian royal princes might not after all be set up as a vassal ruler in

Georgia

under Russian supervision, Tsitsianov at once stifled

the project. 24

The successes won by Tsitsianov

and the rapid expansion of Russian influence throughout Transcaucasia were a

source of extreme concern to the Ottoman Porte and to the Shah of Persia, as

well as to the East India Company and the British Foreign Office. The Shah

was at this time in the enviable position of having rival French and British

missions in Tehran

vying for his favour. In 1805, profiting by Russia's

heavy commitments in the struggle against Napoleon in Europe,

the Persian crown prince, ' Abbas Mirza,

invaded the Karabagh and menaced Elizavetpol. The Russians stood firm, until finally the

Shah's forces retired discouraged and without engaging battle.

Prince Tsitsianov

now judged the time ripe to extend Russia's

dominions to the shores of the Caspian Sea

south of the Caucasian range. In January 1806, he marched on Baku. The khan who

governed that place as a nominal vassal of the Persian shah feigned

submission, and undertook to hand over the keys of the city. As Tsitsianov rode out to meet the khan and his followers,

the Persians opened fire and shot him down on the spot. The artillery of the

citadel started up a bombardment, and the demoralized and leaderless Russians

withdrew. So ended the brief but eventful viceroyalty of this determined

proconsul, a renegade to his own people, but a man who, in serving Russia, dealt many a crushing blow to Georgia's

traditional enemies.

The decade which followed Tsitsianov's death was less spectacular than these first

few years, in which Russian power had spread so rapidly through Transcaucasia. Tsitsianov's

successors were less talented than he. The element of surprise which had

enabled the Russians to overcome the petty Caucasian states one by one was

now lost; the Persian shah and the Turkish sultan were on the alert, and

neither the British nor the French could view with approval this Russian

wedge being driven down towards Mesopotamia and the Levant on the one side,

and towards the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean on the other. Furthermore,

the Napoleonic wars imposed an immense strain on Russia's

resources, and prevented the deployment of large forces in remote Caucasia. Nor can one overlook the deterioration of

relations between the native Georgian population and the occupying power,

resulting from the exactions of the military commanders and the corrupt ways

of Tsarist officialdom.

'Up to 1812,' wrote a staff officer serving

at that time in the Russian Army of the Caucasus,

'the Georgians, organized as irregular troops, had served in our ranks

virtually as volunteers. A disastrous expedition against Akhaltsikhe,

in which they felt themselves to have been sacrificed and abandoned, the

resulting misfortunes, combined with requisitions and extortions, drove them

to revolt. Rebellion was stifled in blood; but its spirit lived on. Only an

entirely new approach can reawaken the fidelity which an odious system has

almost extinguished.' 25

Under Tsitsianov's

successors, the war against Persia

and Turkey

continued with varying success and great ferocity. On the Persian front, Derbent and Baku were at

last annexed in 1806, though a second attack on Erivan

in 1808 ended in another costly failure. In Western Georgia, the Russians

kept up their pressure on the Turks, from whom they took the Black Sea port of Poti in 1909, Sukhum-Kaleh

on the coast of Abkhazia in 1810, and the strategic town of Akhalkalaki ('New Town') in south-western Georgia

in 1811.

King

Solomon II and Napoleon Bonaparte

The remaining independent princes of Western Georgia hastened to accept Russian suzerainty.

In 1809, Safar Bey Sharvashidze,

the Lord of Abkhazia, was received under Russian protection and confirmed in

his principality. Prince Mamia Gurieli,

ruler of Guria, was taken under the Russian aegis

in 1811, receiving insignia of investiture from the Tsar. Only King Solomon

II of Imereti held out to the bitter end.

Encircled by Russian troops, the king

strenuously resisted an demands for submission, in

spite of the fact that he had earlier, under pressure, sworn fealty to the

Tsar. In 1810, the Russians despatched an ultimatum to Solomon, demanding

that he hand over the heir to his throne and other Imeretian

notables as hostages, and reside permanently under Russian surveillance in

his capital at Kutaisi.

Solomon refused, and was declared to have forfeited his throne. Hounded by

Russian troops and by Georgian princes hostile to

him, he sought refuge in the hills, but was soon captured and escorted to Tbilisi. A few weeks

later, Solomon staged a dramatic escape from Russian custody, and took refuge

with the Turkish pasha at the frontier city of Akhaltsikhe.

Inspired by this daring feat, the people of Imereti

rose against the Russian invaders. Ten fierce engagements were fought between

the Russian forces and the guerillas of Imereti. Famine and plague broke out, and some 30,000

people perished, while hundreds of peasant families sought refuge in Eastern Georgia. Eventually the patriots were crushed

by armed force. A Russian administration was set up in Kutaisi, the country placed under martial

law.

King Solomon now applied for help to the

Shah of Persia, to the Sultan of Turkey, and to Napoleon Bonaparte himself.

To the Emperor of the French, Solomon wrote in 1811 that the Muscovite Tsar

had unjustly and illegally stripped him of his royal estate, and that it

behoved Napoleon, as supreme head of Christendom, to 'take cognizance of the

act of pitiless brigandage' which the Russians had committed against him.

'May Your Majesty add to your glorious titles that

of Emperor of Asia! But may you deign to liberate me, together with a million

Christian souls, from the yoke of the pitiless emperor of Moscow, either by

your lofty mediation, or else by the might of your all-powerful arm, and set

me beneath the protective shadow of your guardianship!" 26 Napoleon

himself was, of course, quite a connoisseur of 'pitiless brigandage'.

However, this eloquent plea, which reached him shortly before he set out on

his ill-fated campaign to Moscow, provided him with encouraging evidence of

the unsettled condition of Russia's Transcaucasian

provinces. But as things turned out, Napoleon could not save even his own

Grand Army from virtual annihilation, let alone a princeling

down in the distant Caucasus. Without

regaining power, Solomon died in exile in 1815, and was buried in the

cathedral of Saint Gregory of Nyssa in Trebizond.

The elimination of King Solomon did not

bring civil strife in Georgia

to an end. No sooner was Western Georgia

outwardly pacified than fresh troubles broke out in Kartli

and Kakheti. Ten years of Russian occupation had

greatly changed the attitude of a people who, a decade before, had welcomed

the Russians as deliverers from the infidel Persians and Turks. Called upon

to furnish transport, fodder and supplies to the Russian Army at artificially

low rates, and regarded by their new masters as mere serfs, the Georgian

peasantry looked back wistfully to the bad old days. Under the Georgian

kings, though invaded and ravaged by Lezghis,

Persians and Turks, their country had at least been their own. Now it was

simply an insignificant province, engulfed in a vast, alien empire, whose

rulers seemed lacking in sympathy for this cultivated, Christian nation which

had voluntarily placed itself under the protection of its northern neighbour.

In their yearning for independence, the

Georgians were encouraged by the dauntless personality of Prince Alexander Bagration, son of their great king Erekle

II. Alexander, who had sought refuge with the Shah of Persia, was described

by a contemporary British traveller as 'a prince whose bold independence of

spirit still resists all terms of amity with Russia'. 'It was impossible to

look on this intrepid prince, however wild and obdurate, without interest;

without that sort of pity and admiration, with which a man might view the

royal lion hunted from his hereditary wastes, yet still returning to hover

near, and roar in proud loneliness his ceaseless threatenings

to the human strangers who had disturbed his reign.' 27

The

revolt of 1812

In 1812, the Persians won some military

successes against the Russians in the Karabagh

region. When they heard of the Russian setback, the peasants of Kakheti broke into revolt. They wiped out the garrison of

Sighnaghi and blockaded Telavi,

the capital town of Kakheti. The insurgents

proclaimed as king the young Bagratid

prince, Grigol, son of Prince Ioane,

and grandson of the late King Giorgi XII. In answer

to an ultimatum addressed to them by the Russian commanderin-chief,

Marquis Philip Paulucci, the rebels replied:

'We know how few we are compared with the

Russians, and have no hope of beating them. We wish rather that they would

exterminate us. We sought the protection of the Russian Tsar, God gave it to

us, but the injustices and cruelty of his servants have driven us to despair.

We suffered long! And now, when the Lord has sent us this terrible famine,

when we ourselves are eating roots and grass, you violently seize food and forage

from us! We have been expelled from our homes. Our storerooms and cellars

have been plundered, our stocks of wine uncovered, drunk up and wantonly

polluted by the gorged soldiery. Finally our wives and daughters have been

defiled before our eyes. How can our lives be dear to us after such ignominy?

We are guilty before God and the Russian Tsar of steeping our hands in

Christian blood, but God knows that we never plotted to betray the Russians.

We were driven to this by violence, and have resolved to die on the spot. We

have no hope of pardon, for who will reveal our condition to the emperor? Do

we not remember that when we called on the Tsar's name, our rulers would

answer: God is on high, the emperor far away.' 28

The rebellion spread like wildfire. Even

the Russian authorities in Tbilisi

felt themselves menaced. Prince Alexander Bagration

arrived in Daghestan from Persia to mobilize the Lezghis,

those inveterate foes of both Georgia

and Russia.

But Russian reinforcements were hurried to the scene. The rebels lacked

cohesion, discipline, supplies. In October 1812, the Russians defeated

Alexander and his motley horde at Sighnaghi. A few

days later, the daring Russian commander, Kotlyarevsky,

crossed the River Araxes and defeated the main Persian Army at Aslanduz, leaving 10,000 of the enemy dead upon the field

of battle.

Neither the Russians nor their Persian and

Turkish adversaries were in a fit state to continue the struggle. Peace with

the Ottoman Empire had already been concluded at Bucarest

in May 1812,whereby the Russians handed back to the

Turks the Black Sea port of Poti and the strategic

town of Akhalkalaki.

More favourable to Russia

were the terms of the Treaty of Gulistan, concluded

between Tsar Alexander I and Fath'Ali Shah of

Persia in 1813, largely through the mediation of the British ambassador to Persia,

Sir Gore Ouseley. By this instrument, Russia was confirmed in possession of Eastern

and Western Georgia, Daghestan, and the Muslim

khanates of Karabagh, Ganja,

Shekki, Shirvan, Derbent, Baku

and Kuba.

Suppression

of the Georgian

Church

An event which caused the greatest

resentment throughout Georgia,

and contributed still further to the deterioration of Russo-Georgian relations,

was the suppression in 1811 of the independent Georgian Church.

It will be recalled that the Russo-Georgian treaty of 1783 had guaranteed to

the Patriarch of Georgia the eighth place among the prelates of Russia

and a seat in the Russian Holy Synod. Now, having abolished both the Georgian

monarchies, the Russians found that the Church was becoming a focus for

Georgian national solidarity. With that same scant regard for treaty rights

which it had shown even earlier, the Russian government now sent the CatholicosPatriarch Antoni II

into enforced retirement at St. Petersburg,

replacing him by a representative of the Russian Church,

the Metropolitan Varlaam, who was given the title

of Exarch of Georgia. This complete suppression of

a national Church by the government of a friendly Christian power must be

without parallel in the modern annals of civilized nations.

Himself a Georgian of

noble birth, Varlaam failed to show himself

sufficiently obedient to the will of his Russian masters. He was soon replaced

by a Russian cleric, Theophilact Rusanov, a man

quite alien to Georgian ways. Theophilact regarded

his flock as ignorant barbarians, and did his utmost to replace the Georgian

liturgy with Slavonic forms of worship. In spite of the Russian bayonets which

he had at his disposal, Theophilact encountered

strong opposition throughout Georgia.

In 1820, the Russians arrested the Archbishops of Gelati

and Kutaisi, the principal ecclesiastical

leaders of Western Georgia. Archbishop Dositheus of Kutaisi,

stabbed and maltreated by Russian Cossacks, died soon afterwards. Spontaneous

uprisings followed these Russian outrages. The insurgents planned to restore

the monarchy of Imereti. The upland district of Ratcha was the scene of bitter fighting. The movement

also spread into Guria and Mingrelia.

An outbreak of civil war in Abkhazia in 1821 further aggravated the

situation. The general unrest was not quelled until 1822.

The Russian proconsul in Georgia between 1816 and 1827 was

General A. P. Ermolov, one of the heroes of the

Napoleonic wars. Ermolov, who had taken part in the

battles of Austerlitz, Borodino

and many others, was a man of unsurpassed courage, spartan

in his habits, and adored by his troops. He declared a war to the death

against the Muslim tribesmen of Daghestan and North

Caucasia, and his campaigns, conducted on the good old plan with fire and

sword, the devastation of crops, the sacking of villages, the massacre of men

and the ravishing of women, gave them a lesson which they doubtless

appreciated to the full. Another Russian general said of Ermolov

that 'he was at least as cruel as the natives themselves'. He himself

declared:

'I desire that the terror of my name should

guard our frontiers more potently than chains of fortresses, that my word

should be for the natives a law more inevitable than death. Condescension in

the eyes of Asiatics is a sign of weakness, and out

of pure humanity I am inexorably severe. One execution saves hundreds of

Russians from destruction, and thousands of Mussulmans

from treason.' 29

Ermolov's administration

resulted in improved public security within Georgia. A police force was

founded in Tbilisi.

Bands of marauding Lezghis dared no longer carry

off villagers into slavery or raid trading caravans. Military and post roads

were built, benefiting trade and communications. Ermolov

had some of the Tbilisi

streets paved, and roofed over the bazaar. The erection of European public

buildings helped to modernize the city's appearance. Similar improvements

were undertaken in Kutaisi,

the old capital of Imereti, until now a decayed and

insignificant township.

General Alexei Petrovich

Ermolov

Economic progress and literary contacts

Now that Russia

controlled a stretch of territory extending from the Black

Sea to the Caspian, commerce began to revive. Odessa

in southern Russia

was linked by sea with the little port of Redut-Kaleh

in Mingrelia. By this route, manufactured goods

from Russian cities and Western Europe could be transported via Tbilisi to Baku on the

Caspian, or into Persia

overland via Tabriz.

Tsar Alexander's edict of 1821 granted to Russian and foreign concerns

operating in Georgia

special customs concessions and other privileges for a space of ten years. Tbilisi merchants began to establish connexions with Marseilles, Trieste, and Germany, and to re-export European wares to Persia

on a substantial scale. In 1825, Georgian and Armenian traders made purchases

totalling over a million rubles at the Leipzig fair; in 1828,

the figure exceeded four million. The demand for European manufactured goods

was stimulated by the presence in Georgia of a large number of

Russian officers and civilian functionaries, with their families. In 1830, an

official of the finance department reported from Tbilisi that trade was in the most

flourishing condition. British, French and Swiss commercial houses showed

interest in this growing market.

Imports of Western manufactured goods,

however, far outweighed Georgian exports of raw materials. In 1824, for

instance, the Acting French Consul in Tbilisi reported that although Georgia

produced timber, cotton, saffron, madder, wax, honey, silk and tobacco, there

was little attempt as yet to market these commodities on a large scale. By

Western commercial standards, Georgia

could not furnish a worthwhile cargo of goods for export at any one time,

while acts of piracy by the Circassians and

Abkhazians on Black Sea shipping made sea

trade hazardous. 30

General Ermolov

did his best to remedy these difficulties. The French Consul, the Chevalier

de Gamba, was granted a concession in Imereti to exploit the country's vast timber resources,

and to start up cotton plantations. Five hundred families of Swabian peasants from Württemberg arrived in Georgia

in 1818. They were encouraged to set up model farmsteads near Tbilisi and elsewhere.

They set an admirable example of diligence, thrift and sobriety, which

contrasted with the fecklessness of the local inhabitants. But they remained

aloof from the population at large, with whom they had nothing in common.

They were respected rather than liked, and their influence on the general

life and history of Georgia

was small. Other branches of industry encouraged by Ermolov

were the cultivation of silk in Kakheti, and the

production of wine, for which that same province had always been famed. It

would, however, be wrong to imagine that Russia

benefited financially at this period from her colonization of Georgia.

In 1825, her total revenue derived from the country amounted to 580,000 rubles, which did not even pay for the maintenance of the

local Russian garrisons and administration.

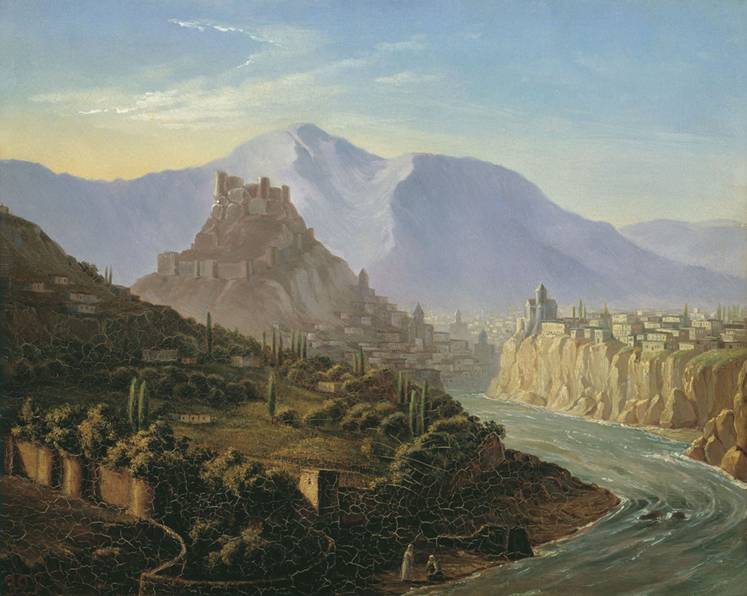

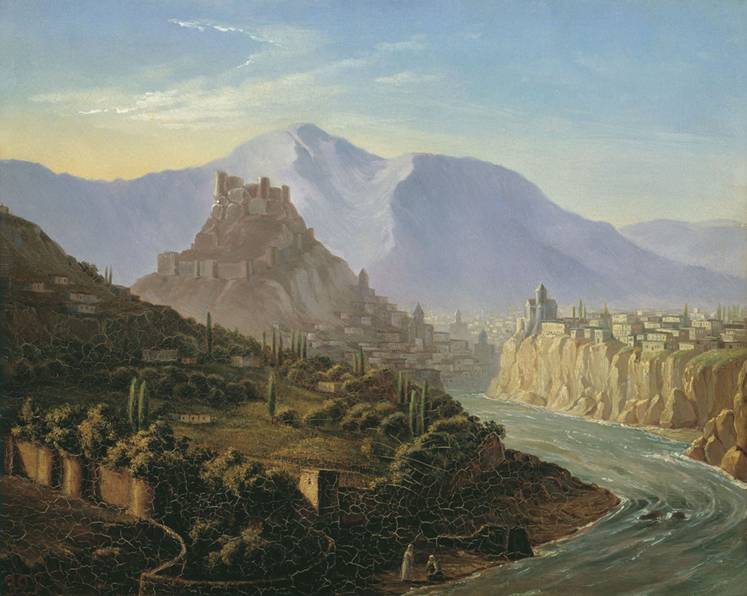

Tbilisi in the early 19th

century (picture by Mikhail Lermontov / 1837)

During the 1820's, the influence of the

Russian Finance Minister, Count Kankrin, and the

agitation of the Moscow manufacturers led to the triumph of protectionism in

Russia generally and the abandonment of any attempt to promote free trade

with foreign countries. Tariff walls and similar devices were imposed

increasingly for the encouragement of budding home industries. Accordingly,

on the expiration of the tenyear customs franchise

granted for Georgia by the edict of 1821, this was not renewed; merchandise

entering Transcaucasia was subject now to the same high dues as were levied

at Russia's other frontiers. Since no large-scale local factories existed,

this return to protectionism simply impoverished the Tbilisi merchants and hampered the growth

of Georgian trade. European goods soon began to reach Persia via Trebizond and Erzurum

in Turkey,

without passing through Russian territory at all. This put a stop for the

time being to any increase in Georgia's

importance as a stage in the international trade route between Europe and the East.

In the meantime, a series of spectacular

events had brought Ermolov's Caucasian viceroyalty

to an untimely close. Early in December 1825, news was brought to St. Petersburg of the death of Tsar Alexander I at Taganrog. Immediately, a

nationwide crisis arose over the succession to the imperial throne. The

reason for this was that the Grand Duke Constantine, who was governing Poland,

had in 1822 formally renounced the succession to the Russian throne in favour

of his younger brother Nicholas, though this had been kept a closely guarded

state secret. For a time, neither Nicholas nor Constantine would accept the

imperial succession, until finally Nicholas was prevailed upon to do so.

Clandestine revolutionary societies had for

some years been active among the younger, liberal-minded officers of the

Russian army. Many of the conspirators belonged to the foremost princely

families in the land. The unsettled state of public opinion now provided them

with what they deemed a propitious moment for their projected coup. On 26

December 1825, when called upon to take the oath of allegiance to the new

emperor, Nicholas I, 2,000 soldiers of the Guard formed up outside the Senate

building in St. Petersburg, shouting for 'Constantine and Constitution (konstitutsiya)' which latter many of the soldiers

took for the name of the Grand Duke Constantine's wife. The military governor

of St. Petersburg

was killed while parleying with the mutineers. Finally, loyal troops were

brought up and two volleys of grapeshot cleared the square. 31 The

resulting investigation revealed that the conspiracy had wide ramifications

throughout Russia.

Five of the ringleaders were hanged, and many others exiled to Siberia or

sent to serve in the ranks of the army of the Caucasus.

Among the many distinguished individuals whose names were mentioned in the

course of the enquiry was General Ermolov. In the

absence of specific evidence against him, he was left at his post, though

under a cloud.

Ermolov was soon under

fire from another quarter. In spite of the Treaty of Gulistan,

which they had signed under duress in 1813, the Persians had never reconciled

themselves to the loss of their Caucasian possessions. In 1825, Ermolov's troops occupied Gokcha,

a small and barren frontier district northeast of Erivan in Armenia. This precipitated a

crisis. Encouraged by garbled reports of the Decembrist uprising, the

Persians decided on an offensive. They were spurred on to action by Prince

Alexander Bagration, the exiled Georgian royal

prince, whose hatred of Russia

overbore any reluctance to subject his native land once more to the horrors

of war. In 1826, the Persian Army launched a surprise attack on Georgia and

the Karabagh. Pambak, Shuragel and Borchalo were

overrun, Elizavetpol (Ganja)

captured. Tbilisi

itself was menaced.

Ermolov reacted with what

can only be termed masterly inactivity. To the urgings of Tsar Nicholas he

responded with pleas for reinforcements. The fire seemed to have gone out of

the veteran warrior.

It was not long before the dashing General Paskevich arrived to take command in the field. Ermolov was relieved of his post. Paskevich

soon routed the Persians completely. The cities of Erivan, Tabriz

and Ardebil

fell to his victorious army. In February 1828, the Russo-Persian Treaty of Turkmanchai was signed, establishing Russia's frontier on the River

Araxes, where it has ever since remained fixed. 32

The treaty of Turkmanchai

eliminated Persia

as a factor in Caucasian politics. The warlike tribes of Daghestan

were cut off from direct contact with their co-religionists in the Islamic

world outside the borders of the Russian Empire. In future, the Muslims of

the Caucasus were to look to the Turks alone

for support. But the successes won by such commanders as Paskevich

meant that the Ottoman Empire, once a mighty world power, was fighting a

losing battle to hold the passes giving access to the inner homeland of Anatolia. During the century following the Caspian

campaign of Peter the Great, the main chain of the Caucasus

mountains had lost its old importance as an impregnable bastion

shielding the Middle Eastern lands against invasion from the north. Caucasia

had become a base from which Russian political and military power could be

directed westward across Anatolia towards the Mediterranean, southward across

Persia towards the Indian

Ocean, and eastward across the Caspian into the heart of Central

Asia. 33

The conclusion of peace with Persia

set Paskevich free to concentrate on Turkish

affairs. A general war between Russia and the Ottoman Porte was

in prospect. The main Russian objectives were the expulsion of the Turks from

the Black Sea coast, and in particular from the ports of Anapa,

Poti and Batumi; the reconquest

of the former Georgian province of Samtskhe, which

had for centuries now been governed by the Turco-Georgian

pashas of Akhaltsikhe; and the establishment of a

satisfactory frontier which would round off Russia's Transcaucasian

dominions and be defensible against Turkish incursions.

The campaign opened in May 1828, with the

surrender of the Turkish garrison in Anapa to a

combined expedition of the Russian fleet and troops from the Caucasian Line.

Relieved of anxiety on the score of his communications with Russia, Paskevich

then marched on the famous fortress of Kars,

which he captured by storm in June. The next month, the Georgian towns of Khertvisi and Akhalkalaki fell

to the Russians, as well as the port

of Poti.

The key city of Akhaltsikhe

was captured in August, while the Turks in Ardahan

surrendered without fighting. With autumn coming on, Paskevich

suspended operations and retired into winter quarters. He left garrisons in

the captured Turkish strongholds, and withdrew with the bulk of his weary

forces into bases within Georgia.

During the winter, Paskevich visited his imperial

master in St. Petersburg, and impressed upon

him the potentialities of an all-out offensive in Asia Minor.

The general proposed first to conquer Erzurum

and overrun the Armenian highlands; next, to launch a combined operation

against Trebizond, with the support of the Russian Navy; and thirdly, to

advance into the heart of Anatolia by way of Sivas.

Two untoward events delayed the campaign of

1829. On 11 February, the Russian mission to Tehran, headed by the playwright Griboedov, was hacked to pieces by a frenzied mob of

fanatical Persians. Only a display of unwonted moderation by the Russians

prevented a fresh outbreak of war with Iran. This moment, too, was

chosen by the Turks to launch a counter-offensive in the course of which they

reoccupied Ardahan and laid siege to the Russians

who manned the citadel of Akhaltsikhe. At the

beginning of June, Paskevich resumed the offensive.

His brilliant strategy and forceful leadership soon reduced the Turks to a

state of demoralization. Within a month, the Russians were before the great

Turkish fortress of Erzurum, which the Ottoman seraskier

made haste to surrender together with the remnants of his army, one hundred

and fifty fortress guns, and vast stores. The conclusion of the Treaty of

Adrianople in September 1829, forestalled the complete execution of Paskevich's ambitious plan. The terms of this treaty,

dictated by wider issues of European politics, were relatively moderate in

regard to the Ottoman Porte's Caucasian dominions. The Russians gained the

strongholds of Adsquri, Akhalkalaki

and Akhaltsikhe. But the provinces of Erzurum, Bayazid and Kars reverted to the Turks, who also regained Batumi and parts of Guria. The Russians received the ports of Poti and Anapa. The loss of Anapa cut off the Turks from direct access to Circassia, over which the Porte formally renounced all

claim to suzerainty.

These spectacular campaigns had the effect

of making Georgia

an important focus of international affairs. Intellectual life began to

revive as Tbilisi

became more and more of a cosmopolitan centre. There were frequent contacts

between the Georgian aristocracy and visitors from the outside world, both

Russians and travellers from Western Europe.

The first Georgian newspaper, Sakartvelos

gazeti or The Georgian Gazette, was

published between 1819 and 1822. The Russian-language Tiflisskie

vedomosti or Tiflis News started to appear

in 1828, with a supplement in Georgian. Associated with this venture was the

Georgian publicist Solomon Dodashvili, otherwise

known as Dodaev-Magarsky ( 1805-36),

who had attended the University of St. Petersburg and was now a teacher at the government

school in Tbilisi.

Also prominent in the intellectual life of Georgia was Prince Alexander Chavchavadze ( 1787-1846),

father-in-law of the Russian dramatist Griboedov. Chavchavadze's house in Tbilisi was a meeting place for the cream

of Georgian and Russian society. He won renown as a lyric poet, as did Prince

Grigol Orbeliani ( 1800-83), both of them being high-ranking officers in

the Russian Army.

After the abortive Decembrist conspiracy of

1825, the Caucasus was used by the Tsar as a milder alternative to Siberia for political offenders. Many of the exiled

Decembrists served in the ranks of Paskevich's

army. Several of these were poets and novelists of distinction, who found the

hospitable atmosphere of Georgia

highly congenial. The prevailing cult of Byronism in Russia encouraged a mood of romantic

enthusiasm for the snow-capped peaks of the Caucasus,

and their valiant, picturesque denizens. As the Russian critic Belinsky observed, 'The Caucasus seems to have been fated

to become the cradle of our poetic talents, the inspiration and mentor of

their muses, their poetic homeland.' In one of his lyrics, Griboedov describes the charm of Kakheti,

'where the Alazani meanders, indolence and coolness

breathe, where in the gardens they collect the tribute of the purple grape.'

He started work on a romantic tragedy to be entitled Georgian Night,

based on a theme from national legend. The great Pushkin was in Georgia

in 1829. He was royally feted in Tbilisi,

and wrote several lyrics on Georgian subjects. His travel journal, A

Journey to Erzurum, gives an account of his visit to the marchlands of Turkey

in the train of the victorious Paskevich; it

contains glimpses of Georgian life, music, poetry and scenic beauty. Some of

the brilliant inspiration of the great romantic M. Yu. Lermontov came to him

from Georgia.

The poems Mtsyri and Demon have a

Georgian setting, while his ballad Tamara presents a lurid if

historically false image of the great queen. In another of his poetic works,

Lermontov sketches a portrait of a drowsy Georgian countryman, recumbent in

the shade of a plane tree, languidly sipping the mellow wine of Kakheti.

But neither the Russian romantic cult of

the Caucasus, nor the hospitable welcome extended by Tbilisi society to Russian officers and

poets, could efface the deep-seated antagonism which the experience of a

generation of Russian rule had implanted in the Georgian nation. There were

observers who saw with concern the effect which foreign misrule was having on

the Georgian population. One eyewitness, Colonel Rottiers,

a Belgian in the Russian service, went so far as to recommend that Russian

officials be removed altogether from service in Georgia. 'The Georgians,' he

wrote, 'would submit to a governor from among their own nation. They would be

happy to see punished, or at least recalled, the officials of whom they have

had the most to complain. They ask for an administrative system which extends

beyond questions of criminal, civil and commercial law, and would like to

have laws based as far as possible on the code of their ancient kings. It is

wrong to despise as barbarians a people whose aspirations testify at once to

their love of abstract justice, and to so pronounced

a sense of nationality. . . . They desire, finally, to be eligible according

to merit to posts which up to now have been bestowed by favour alone, and,

furthermore, they would like themselves to elect their municipal magistrates,

their mouravs or justices of the peace.

"But," you may say, "these folk are as good as demanding a

constitution!" And why not? Those who have seen them at close quarters

deem them ripe for this privilege. When it is a question of bestowing liberty

on a nation, that is the crucial point at issue.' 34

The conspiracy of 1832

The moral climate of the 1820's was

conducive to romantic nationalism and to movements of revolt against imperial

systems. Throughout Europe, the ideals

typified by the Holy Alliance and the policies of Metternich and the Russian

autocrats were being called in question by thinking men. The activities of

the Carbonari in Naples,

the liberation movement in Greece,

the abortive Decembrist rising in Russia,

the Paris revolution of 1830 and the general

insurrection in Poland,

were all symptoms of a general malaise.

The Georgians had not forgotten their

chivalrous days of old, and the general mood of romantic effervescence found

response in their hearts. There were also material causes of grievance. Even

the higher aristocracy were discontented, especially as the Russian

administration had curtailed the landlords' feudal jurisdiction over their

peasants and ousted them from participation in local government, as well as questioning

the titles of nobility of some of the leading princely families. Continual

wars had bled the country white. The Russian writer

Griboedov commented in 1828 that 'the recent

invasion by the Persians, avenged by Count PaskevichErivansky

with so much glory for Russia, and the triumphs which he is now winning in

the Turkish pashaliks, have cost the Transcaucasian provinces enormous sacrifices, above all Georgia,

which has borne a war burden of exceptional magnitude. It is safe to say that

from the year 1826 up to the present time she has suffered in the aggregate

heavier losses in cereal crops, pack animals and beasts of burden, drovers,

etc., than the most flourishing Russian province could have sustained.' 35 The

prevailing mood was aptly summed up in a quatrain by Prince Ioane Bagration, son of the

last king of Kartlo-Kakheti, Giorgi

XII:

The Scythians [i.e., Russians] have taken

from us the entire land, and not even a single serf have they given to us.

Not satisfied with Kartli and Kakheti,

they have added to them even Imereti. We have grown

poor in misfortune, and have no advocate to whom to turn. We ask justice from

above; we shall see how God decrees!

A striking portrayal of the results of a

generation of Russian rule over Georgia

is contained in the report submitted by two Russian senators, Counts Kutaysov and Mechnikov, who

carried out an official inspection of Georgia in 1829-30. The state of

affairs displayed in this document resembles that so effectively pilloried in

Gogol's comedy, Revizor, or The Inspector-General.

'Not in a single government chancellery in Transcaucasia is there a shadow of that order in the

forms and procedure of transacting business which is prescribed by law. In

some chancelleries, this is because of their defective organization; in

others, because of the incapacity and lack of experience of the officials

posted for service there, and the complete absence of personnel capable of

efficient work. . . . The quantity of unresolved lawsuits turned out to be

beyond calculation. They had piled up, not because they were submitted in

great quantities, but because no efforts were made to bring them to a prompt

settlement.'

According to these two senators, Russian

officials were volunteering to serve in Georgia

simply in order to benefit by the advancement in rank automatically granted

as an incentive to undertake a tour of duty in the Caucasus.

On arrival there, they spent their period of service in wandering idly from

one department to another, and waiting impatiently for the moment to return

home. Arbitrary caprice rather than observance of official regulations

governed the administration of justice. Thus, the Governor of Tbilisi, P. D. Zavaleysky, and his colleagues, had deprived some

proprietors of their lands, and granted these to others, just as they saw

fit. 'In Imereti', the senators went on, 'we found

abuses of power and acts of extortion.' The main culprits were the head of

the local administration, State Councillor Perekrestov,

and his colleagues. The senators removed these persons from office and

committed them for trial. The general muddle was further aggravated by the

right which the Russian commanders-inchief at

Tbilisi had arrogated to themselves of acting as supreme judges of appeal,

and sometimes forcing local tribunals to give verdicts against the canons of

Russian law, in which nobody therefore had any faith. 'Although certain

provinces have been joined to Russia

for about thirty years,' the senators continued, 'the administration in Transcaucasia still bears the stamp of the

irresponsible, capricious and vague methods of government practised by the

former rulers of this country.' This applied particularly to the basis of

land tenure and the system of serfdom. 'Some peasants exercise rights of

ownership over other peasants, as if they were themselves members of the

gentry class. . . . The princes there possess nobles as their vassals, and

dispose of their persons as well as of their property.' The dues and services

rendered by the peasants to their proprietors were innumerable, and not

defined by any law. The lot of the farmers was rendered intolerable by the

behaviour of Russian quartermasters. When grain and other supplies needed for

the troops were commandeered, often at artificially low prices, payment was

frequently withheld and embezzled by the military commanders themselves.

There were even cases where the authorities acted as receivers of stolen

property, and protected the thieves from prosecution by the rightful owners.

Senators Kutaysov

and Mechnikov went on to underline the backward

state of the social services and public amenities in Georgia. There were no charitable

foundations, orphanages, almshouses, homes for incurables, or lunatic asylums.

One small, wretched hospital served the needs of the entire population.

Public hygiene and the study of tropical diseases demanded urgent attention.

The towns were still dirty and squalid in appearance. There were no regular

travel facilities or posting stations. The income of the Georgian Exarchate

was not being spent, as it should have been, in keeping the churches under

its authority in good repair. The churches in both Eastern

Georgia and Imereti were in a wretched

and dilapidated condition. Some of these, which the senators recognized as

possessing outstanding architectural merit and historical interest, were

literally falling down; others had holes in the roof, through which rain

poured down upon the worshippers. The senators concluded by informing the

emperor that they had uncovered in the administration of Transcaucasia

abuses, malpractices and oppression of the people, and had endeavoured to put

an end to these once for all. They hoped that the state of Georgia would swiftly take a turn

for the better. 36 This

hope, as it turned out, was a trifle premature.

It was natural, given these conditions, that the Georgians should have yearned for the

removal of Russian dominance and the return of the house of Bagration. The senior members of the Georgian royal

family were by now dead, or else for the most part resigned to exclusion from

power. An exception was Prince Alexander Bagration,

who was still living among the Persians, and ever on

the alert for a chance of action against the hated Russians. Within Russia,

the spirit of Georgian nationalism was kept alive principally by Okropir Bagration, a younger

son of King Giorgi XII and the heroic Queen Mariam, and also by his cousin, Prince Dimitri, son of Yulon. Okropir and Dimitri used to

hold gatherings of Georgian students at Moscow

and St. Petersburg,

and attempted to inspire them with patriotic feeling. A secret society was

formed in Tbilisi

to work for the re-establishment of an independent kingdom under Bagratid rule. Okropir himself

visited Georgia

in 1830, and held talks with the principal conspirators, who included members

of the princely houses of Orbeliani and Eristavi, as well as the publicist Solomon Dodashvili. They hoped to enlist the support of Western

Georgian nationalists who had been active in the revolt in Imereti in 1820. The young Constantine Sharvashidze, a scion of the ruling house of Abkhazia,

was also believed sympathetic.

The Georgian conspirators of 1830-32 were

not liberal republicans, but rather monarchists and nationalists. Their

projected plan of action was melodramatic rather than practical. It was

proposed to invite Baron Rosen, who had succeeded Paskevich

as commander-in-chief in Georgia, and other members of the garrison and

administration, to a grand ball in Tbilisi.

At a given signal, they would all be assassinated. The conspirators would

then seize the Daryal

Pass to prevent reinforcements from

arriving from Russia.

Prince Alexander Bagration would return from Persia to be proclaimed king of Georgia.

Plans for seizing the arsenal and barracks were drawn up, as was the

composition of a provisional government.

This rather wild project proved

unacceptable to the more moderate members of the group. Many of the Georgian

nobles had, after all, friends or relatives by marriage among the Russian

residents. The publicist Dodashvili quitted the

conspiracy altogether, while the patriot and poet Alexander Chavchavadze refused to support a scheme which depended

on the support of Prince Alexander Bagration and

his infidel Persians, the murderers of his son-in-law Griboedov.

These waverers refrained, however, from disclosing

their knowledge to the Russian authorities.

The ball at which the Russian officers were

to be assassinated was scheduled for 20 November 1832, the day of the meeting

of Georgian princes and nobles at Tbilisi

for the election of deputies to the Provincial Assembly of the Nobility. This

session was unexpectedly postponed, first to 9 December.,

then to 20 December.

Early in December, the whole affair was

revealed to the authorities by one of the conspirators, who turned 'King's

Evidence'. Extensive arrests were made. Commissions of enquiry were set up at

Tbilisi and in St. Petersburg. Although ten of the accused

were sentenced to death, they were all reprieved. Some of them were deported

for a few years to provincial centres in Russia, or enrolled in the ranks

of the Russian Army. The writer Dodashvili, already

a consumptive, was posted to Vyatka, the

harsh climate of which place soon brought him to the

grave.

The Emperor Nicholas was perturbed by the

well-founded grievances revealed by the commissions of enquiry, and ordered a

thorough investigation into the causes of discontent. Most of the conspirators

were later allowed to resume their official careers, and one of them, Prince Grigol Orbeliani, rose to be

Governor of Tbilisi. The failure of the plot of 1830-32 marks the end of an

epoch in Georgian history. All hope for a restoration of the Bagratid dynasty was now lost. The Georgian aristocracy

came more and more to identify their own interests with those of the Russian

autocratic régime. Georgia sank gradually into a

mood of torpid acquiescence, until the economic and intellectual revival which

occurred during the viceroyalty of Prince Vorontsov,

between 1845 and 1854, paved the way for a fresh upsurge of national

consciousness.

Click here

to continue

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

20. See

Russian sources cited in D. M. Lang, The Last Years of the Georgian

Monarchy, p. 254.

21. We

follow the version given by Colonel B. E. A. Rottiers,

in his Itinéraire de Tiflis à

Constantinople, Brussels

1829, pp. 73-83.

22. J.F.

Baddeley, The Russian Conquest of the Caucasus,

London 1908,

p. 68.

23. Cited

in D. M. Lang, The Last Years of the Georgian Monarchy, p. 257.

24. D.

M. Lang, The Last Years of the Georgian Monarchy, p. 259.

25. Rotfiers, Itiéraire

de Tiflis à Constantinople, pp. 94-95.

26. French

diplomatic archives, Quai d'Orsay, Paris,

as quoted in M. Lang, The Last Years of the Georgian Monarchy, pp. 263-65.

27. Sir

Robert Ker Porter, Travels in Georgia,

Persia, etc., Vol. II,

London 1821-22,

p. 521.

28. D.

M. Lang, The Last Years of the Georgian Monarchy, pp. 267-68.

29. Quoted

in Baddeley, The Russian Conquest of the Caucasm, p. 97.

30. Archives

of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Quai d'Orsay, Paris,

Correspondance Commerdale,

Tiflis, Vol. I,

pp. 107-8.

31. See

Sir Bernard Pares, A History of Russia, revised edition, London 1947,

p. 365; D. M. Lang, "The Decembrist Conspiracy through British

Eyes", in American Slavic and East European Review, Vol. VIII,

No. 4, December 1949, pp. 262-74.

32. D.

M. Lang, "Griboedov's Last Years in

Persia", in American Slavic and East European Review, Vol. VII,

No. 4, December 1948, pp. 317-39.

33. W.E.

D. Allen and P. Muratoff, Caucasian

Battlefields: A History of the Wars on the Turco-Caucadan

Border, 1928-1921, Cambridge

1953, p. 21.

34. Rottiers, Itinéraire

de Tifiis à Constantinople,

p. 95.

35. Text

in D. M. Lang, The Last Years of the Georgian Monarchy, pp. 275-76.

36. See

the text of the report in the Akty or

Collected Documents of the Caucasian Archaeographical

Commission (in Russian), Vol. VIII, Tbilisi

1881, pp. 1-13.

|

|