|

|

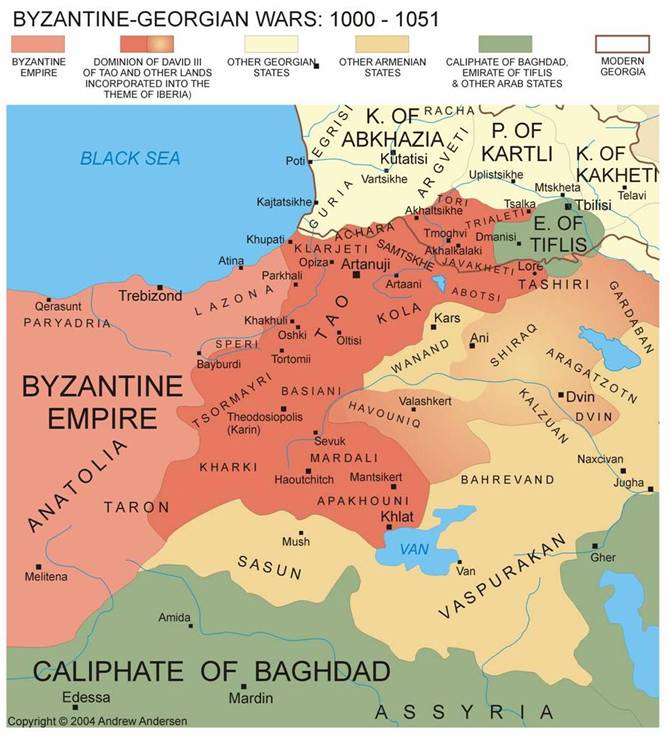

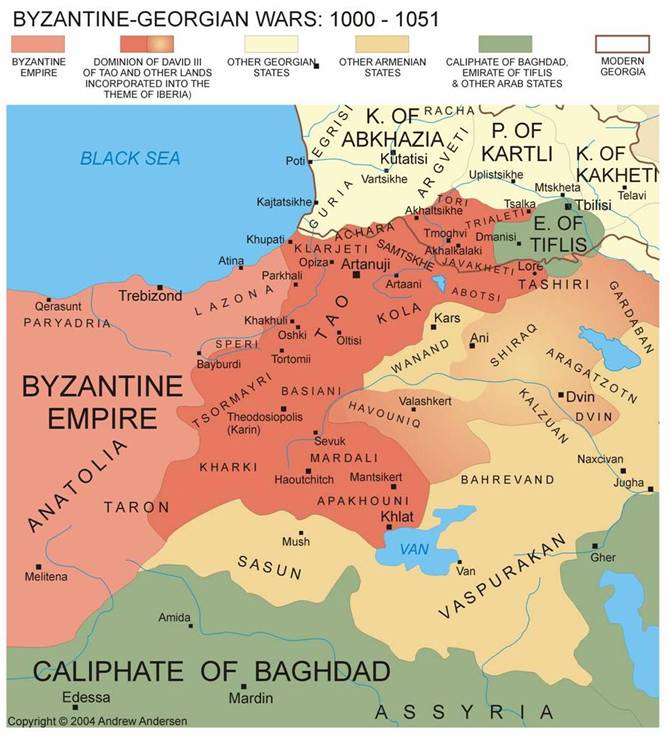

The Theme of Iberia (Greek:

θέμα 'Ιβηρίας) was an

administrative and military unit – theme – within the Byzantine Empire curved

by the Byzantine Emperors out of several Georgian and Armenian lands in the

eleventh century. It was formed as a result of Emperor Basil II’s annexation

of a portion of the Georgian Bagratid domains (1000-1021) and later

aggrandized at the expense of several Armenian kingdoms acquired by the

Byzantines in a piecemeal fashion in the course of the eleventh century. The

population of the theme was multiethnic with the Armenian and Georgian

majority, including a sizable Armenian community of Chalcedonic rite to which

the contemporary Byzantines expanded, as a denominational name, the ethnonym

"Iberian", a Graeco-Roman designation of Georgians[1].

The theme ceased to exist in 1074 AD as a result of the Seljuk invasions.

Foundation of the Theme Enlargement

The

theme was created by the emperor Basil II (976-1025) from the lands inherited

from the Georgian prince David III of Tao. These areas – parts of the

Armeno-Georgian marchlands centered on Thither Tao/Tayk as well as several

northern districts of western Armenia including Theodosioupolis (Karin; now

Erzurum, Turkey), Basean, Hark’, Apahunik’, Mardali (Mardaghi), Khaldoyarich,

and Ch’ormayari – had been granted to David for his crucial assistance to

Basil against the rebel commander Bardas Sclerus in 979. However, David’s

rebuff of Basil in Bardas Phocas’ revolt of 987 evoked Constantinople’s

distrust of the Caucasian rulers. After the failure of the revolt, David was

forced to make Basil II the legatee of his extensive possessions.[2]

Basil gathered his inheritance upon David’s death in 1000, forcing the

successor Georgian Bagratid ruler Bagrat III to recognize the new

rearrangement in accordance with which Tao, Theodosiopolis (aka Karin, Karnukalaki;

the present day Erzurum), Phasiane (Basiani)

and the Lake Van region (Apahunik) with the city of Manzikert

were annexed by the Byzantine Empire.

The

following year, the Georgian prince Gurgen, natural father of Bagrat, marched

to take David’s inheritance, but was thwarted by the Byzantine general

Nikephoros Ouranos, dux of Antioch.

Despite these setbacks, Bagrat was able to become the first king of the

unified Georgian state in 1008. He died in 1014, and his son, George I, inherited

a longstanding claim to David’s succession which was in Byzantine hands.

Georgian campaigns of Basil II and

Enlargement of

the Theme

While

Basil was preoccupied with his Bulgarian campaigns, George gained momentum to

invade Tao/Tayk and Basiani/Phassiane in 1014. Basil, involved in his

campaign against the Bulgarians, sent an army to expel the Georgians. This

army was decisively defeated, but a Byzantine naval force occupied the Khazar

ports in the rear, that is, to the north-west, of George's dominions. Once,

the annexation of Bulgaria

was completed in 1018, preparations for a larger-scale campaign were set in

train, beginning with the refortification of Theodosiopolis. In the autumn of

1021, Basil with a large army, reinforced by the Varangian Guards, attacked

the Georgians and their Armenian allies recovering Phasiane and pushing on

beyond the frontiers of Tao into inner Georgia. King George burned the

city of Olthisi

for not to fall in the enemy’s hands and retreated to Kola. A bloody battle

was fought near the village Shirimni at the Lake

Palakazio (now Çildir, Turkey)

on September 11. The emperor won a costly victory, and forced George I to

retreat northwards into his kingdom. Plundering the country on his way, Basil

withdrew to winter at Trapezus (Trebizond, now Trabzon, Turkey).

Several attempts to negotiate the conflict went in vain. In the meantime

George received reinforcements from the Kakhetians, and allied himself with

the Byzantine commanders Nicephorus Phocas and Nicephorus Xiphias in their

abortive insurrection in the emperor’s rear. In December, George’s ally, the

Armenian king Senekerim of Vaspurakan, being harassed by the Seljuk Turks,

surrendered his kingdom to the emperor.

With the

spring of 1022, Basil launched a final offensive winning a crushing victory

over the Georgians at Svindax Defeated and menaced both by land and sea, King

George had to relinquish Tao, Phasiane, Kola, Artaani and Javakheti – to the Byzantine

Crown, and left his infant son Bagrat a hostage in Basil's hands[3].

The conquered provinces were re-organized by Basil II into the Theme of Iberia with the capital at

Theodosiopolis. As a result, the political center of the Georgian state moved

north, as did a significant part of the Georgian nobility[4],

while the empire gained a critical foothold for further expansion into the

territories of Armenia and

Georgia.

Basil next claimed the principal Armenian Bagratid kingdom of Ani,

currently straddling the division between Gagik I’s sons, John-Smbat and

Ashot I. In 1022, John-Smbat, as penalty for having supported Georgia, yielded his appanage to the Byzantine Empire. By the mid-1040s, Emperor Constantine

IX (1042-55) had broken the resistance of the survived Bagratids of Ani and

forced the catholicos Peter into surrendering Ani in 1045.[5]

The kingdom was merged with the theme of Iberia and the capital was

transferred from Theodosioupolis to Ani. Henceforth, the theme of Iberia was administered jointly with Greater

Armenia and the enlarged theme was frequently referred to as the "theme

of Iberia and Armenia".[6]

In 1064 the last independent Armenian kingdom, that of Wanand with its center

in Kars, was absorbed into imperial territory when Gagik II of Kars was

bullied into abdication in favor of Emperor Constantine X (1059-67) to

prevent his state from being conquered by the Seljuk Turks. The royal family

moved to Cappadocia, probably accompanied by

their nobility who were inveigled by the Byzantine administration into ceding

their estates in return for lands further west[7].

The event was preceded by the Seljuk capture of Ani and the theme’s center

was shifted back to Theodosioupolis[8].

|

Click

on the map for better resolution

|

|

The Byzantine Empire and the Civil

wars in Georgia

On the death of

his father, Bagrat returned home to become King Bagrat IV of Georgia

in 1025. However, a powerful party of Georgian nobles refused to recognize

his suzerainty, and invited a Byzantine army in 1028. The Byzantines overran

the Georgian borderlands and invested Kldekari, a key fortress in Trialeti

province, but failed to take it and marched back on the region Shavsheti. The

local bishop Saba of Tbeti organized a successful defense of the area forcing

the Byzantines to change their tactics. The emperor Constantine VIII then

sent Demetrius, an exiled Georgian prince, who was considered by many as a

legitimate pretender to the throne, to take a Georgian crown by force. This

incited a new tide of the rebellion against Bagrat and his regent, queen

dowager Mariam of Vaspurakan. In the end of 1028, Constantine

died, and the new emperor Romanus III recalled his army from Georgia.

Queen Mariam visited Constantinople in

1029/30 and negotiated a peace treaty between the two countries.

Early in the 1040s, a feudal opposition staged another revolt against Bagrat

IV of Georgia.

The rebels led this time by Liparit IV, Duke of Kldekari, requested a

Byzantine aid and attempted to put Prince Demetrius on the throne. Yet,

despite their efforts to take a key fortress Ateni went in vain, Liparit and

the Byzantines won a major victory at the Battle of Sasireti in 1042 forcing

Bagrat to take refuge in the western Georgian highlands. Soon Bagrat headed

for Constantinople and, after the three

years of negotiations achieved his recognition by the Byzantine court. Back

to Georgia

in 1051, he was able to force Liparit into exile. Actually, this was the end

of the Byzantine-Georgian conflicts

Government of the Theme of Iberia

The

exact chronology of the theme of Iberia and of its governors is not

completely clear. Unfortunately, the few Greek seals from the theme or from

the ambiguous "Interior Iberia" can seldom be dated precisely.[9]

Although many scholars maintain that the theme was probably created

immediately after the annexation of David of Tao’s princedom, it is difficult

to ascertain whether Byzantine rule extended into Tao/Tayk permanently in

1000 or only after Georgia’s

defeat in 1022. It is also impossible to identify any commander in Iberia before the appointment, in 1025/6, of the

eunuch Niketas of Pisidia as the Doux

or Catapan of Iberia. Some

scholars believe, however, that the first doux of Iberia was either Romanos

Dalassenos or his brother Theophylactos appointed between 1022 and 1027 in

the aftermath of Basil’s Georgian campaigns.[10]

The Iberian governor was aided by tax officials, judges, and by co

administrators who shared in the exercise of the military and civil duties.

Among these officials were the domesticos of the East, the administrators of

the districts of which the theme was composed, and the occasional

extraordinary legates sent there by the emperor. Apart from the regular

Byzantine garrisons, an indigenous army of peasant soldiers guarded the area

and received in turn an allotment of tax-free government land. This changed,

however, when Constantine IX (1042-1055) dismantled the army of the theme of Iberia,

perhaps 5,000 men, converting its obligations from military service to the

payment of tax. Constantine

dispatched a certain Serblias to conduct an inventory and to exact taxes that

had never been demanded previously.

End of the Theme

Constantine’s reforms caused great discontent in the theme and

exposed it to hostile attack aided by the removal of regular troops from the

region, first to crush the Macedonian revolt of Leo Tornicius, himself the

former catapan of Iberia

(1047)[11],

and later to halt the Pecheneg advance.

In 1048-9, the Seljuk Turks under Ibrahim Inal made their first incursion in

this region and destroyed a combined Byzantine-Armenian and Georgian army of

50,000 at the Battle of Kapetrou on September 10, 1048. Tens of thousands of

Christians are said to have been massacred and several areas were reduced to

piles of ashes. In 1051/52, Eustathius Boilas, a Byzantine magnate who moved

from Cappadocia to the theme of Iberia, found the land "foul

and unmanageable... inhabited by snakes, scorpions, and wild beasts."[12]

The theme of Iberia did

not long survive the Byzantine disaster at the hands of the Seljuk sultan Alp

Arslan at Manzikert, north of Lake Van, on

August 26, 1071. Still, it may have lasted as late as 1074 when Gregory

Pakourianos, a Byzantine governor of Armeno-Georgian background, formally

ceded a portion of the theme including Tao/Tayk and Kars

to King George II of Georgia.

This did not help, however, to stem the Turkish advance and the area became a

battleground of the Georgian-Seljuk wars[13].

Aftermath

Despite the

territorial losses to Basil II and the Seljuk Turks, the Georgian kings

succeeded in retaining their independence and in uniting most of the Georgian

lands into a single state. Many of the ceded territories were then re-taken

after the 1080s by the Georgian King David IV.

Relations between the two Christian monarchies were then generally peaceful

except for the episode of 1204, when Queen Tamar of Georgia took advantage of the Fourth Crusade

against Constantinople, and invaded the Black Sea

provinces of the empire to help the Comnenus Princes to found the Empire of Trebizond.

Recommended Reading

Toumanoff,

Cyril, Studies in Christian Caucasian History (Washington, 1967)

Arutyunova-Fidanyan, Viada A., Some Aspects of the Military-Administrative

Districts and Byzantine Administration in Armenia During the 11th

Century, (Moscow, 1986-87), pp. 309-20.

Kalistrat, Salia, History of the Georgian Nation, (Paris, 1983)

Garsoian, Nina, The Byzantine Annexation of the Armenian Kingdoms in the

Eleventh Century, In: The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times,

vol. 1, edited by Richard G. Hovannisian, (New York, 1977).

Hewsen, Robert., Armenia. A Historical Atlas. (Chicago, 2001)

|

|