|

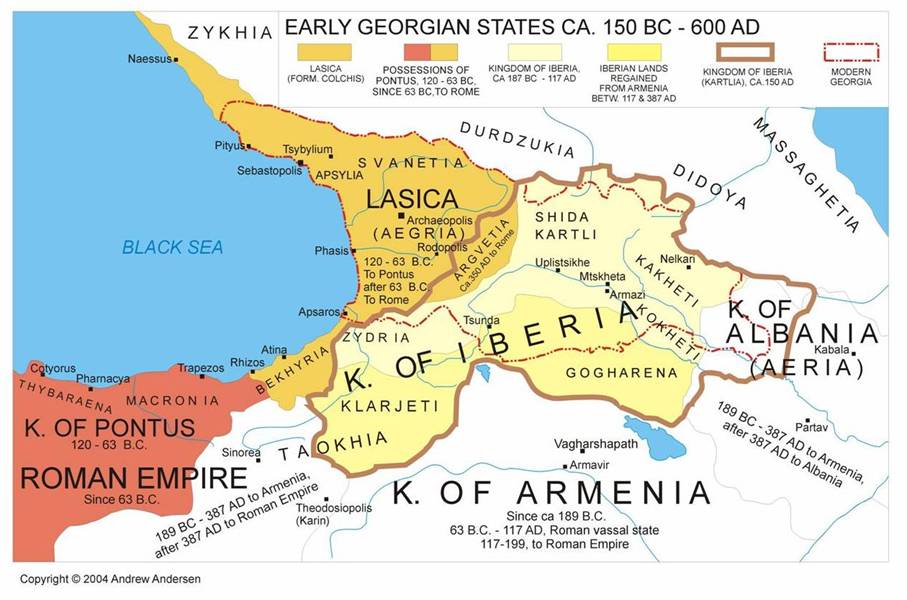

Iberia

(Georgian — იბერია, Latin: Iberia or Iberi and

Greek: Ἰβηρία)

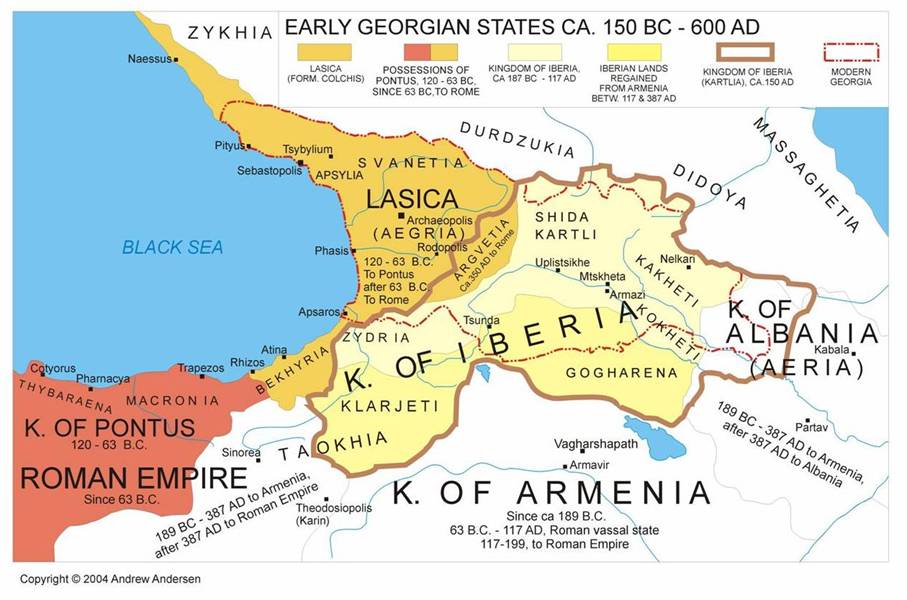

also known as Iveria (Georgian: ივერია) was a name given by the ancient

Greeks and Romans to the ancient Georgian kingdom of Kartli (4th century

BC-5th century AD) corresponding roughly to the eastern and southern parts of

the present day Georgia.

The term “Caucasian Iberia” (or Eastern Iberia) is used to distinguish it

from the Iberian Peninsula, where the present day states of Spain, Andorra

and Portugal

are located. The Caucasian Iberians provided a basis for later Georgian

statehood and formed a core of the present day Georgian people (or

Kartvelians).

EARLIEST HISTORY

The area was inhabited in earliest times by several related tribes,

collectively called Iberians (the Eastern Iberians)

by ancient authors. Locals called their

country Kartli after a mythic chief, Kartlos.

The Moschi mentioned by various classic historians, and their possible

descendants, the Saspers (who were mentioned by Herodotus), may have played a

crucial role in the consolidation of the tribes inhabiting the area. The

Moschi had moved slowly to the northeast forming settlements as they

migrated. The chief town of these was Mtskheta, the future capital of the

Iberian kingdom. The Mtskheta tribe was later ruled by a chief locally known

as Mamasakhlisi (“the father of the

household” in Georgian).

The medieval Georgian source Moktsevai

Kartlisai (“Conversion of Kartli”) speak also about Azo and his people,

who came from Arian-Kartli - the initial home of the proto-Iberians, which

had been under Achaemenid rule until the fall of the Persian Empire - to

settle on the site where Mtskheta was to be founded. Another Georgian

chronicle Kartlis Tskhovreba

(“History of Kartli”) claims Azo to be an officer of Alexander’s armies, who

massacred a local ruling family and conquered the area, until being defeated

at the end of the 4th century, BC, by Prince Pharnavaz, who was a local chief

at that time.

Pharnavaz I and His

Descendants

Pharnavaz, victorious in power struggle, became the first King of Iberia (ca.

302 - 237 BC). Driving back an invasion, he subjugated the neighbouring

areas, including significant part of the western Georgian state of Colchis (locally known as Egrisi), and seems to have

secured recognition of the newly founded state by the Seleucids of Syria.

Pharnavaz then focused on social projects, including the construction of the

citadel in the capital, the Armaztsikhe, and erection of an idol of a god

named Armazi. He also reformed the Georgian written language, and created a

new system of administration subdividing the country into several counties

called saeristavos. His successors

managed to gain control over the mountainous passes of the Caucasus Range

with Daryal (also known as the Iberian Gates) being the most important of

them.

The period following this time of prosperity was marked with incessant

warfare though. Iberia

was forced to defend itself against numerous invasions. As a result, the country

lost some of its southern provinces to Armenia, and the Colchian lands

seceded to form separate princedoms (sceptuchoi). At the end of the 2nd

century BC, the Pharnavazid king Farnadjom was dethroned by his own subjects

and the crown given to an Armenian prince Arshak who ascended the Iberian

throne in 93 BC, establishing the Arshakid dynasty.

ROMAN PERIOD

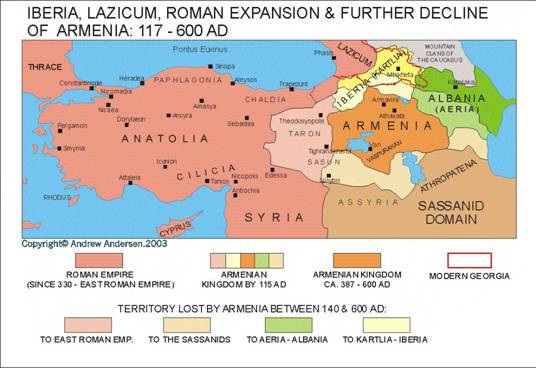

This close association with Armenia

brought upon the country an invasion (65 BC) by the Roman general Pompey, who

was then at war with both Mithradates VI of Pontus,

and Tigran II of Armenia.

However, Rome failed to establish its

permanent power over Iberia.

Nineteen years later, the Romans again marched into Iberia (36

BC) forcing King Pharnavaz II to join their campaign against Caucasian

Albania.

While another Georgian kingdom of Colchis was turned into a Roman province, Iberia

accepted Roman Imperial protection. A stone inscription discovered at

Mtskheta speaks of the first-century ruler Mihdrat I (A.D. 58-106) as

"the friend of the Caesars" and “the King of Roman-loving

Iberians." It was at that period when Emperor Vespasian fortified the

ancient Mtskheta site of Arzami for the Iberian kings in 75 A.D.

|