|

|

|

THE STRUGGLE FOR KARABAKH, NAKHICHEVAN AND OTHER TERRITORIES

DISPUTED BY ARMENIA AND AZERBAIJAN (1918-1920) Andrew ANDERSEN, George EGGE

|

|

|

|

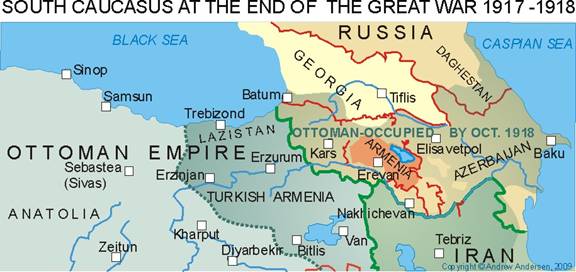

On May 26, 1918, the Transcaucasian

Federation dissolved, and within the next 2 days later independent republics

of Azerbaijan and Armenia were proclaimed. The birth of the new nations was

facing economic disaster, Turkish invasion and political isolation. On June

4, 1918, a peace-treaty was signed in Batum, according to which considerable

part of South Caucasus was assigned to Turkey, most of Georgia remained under

German protectorate and the Armenian Republic was cut down to a tiny enclave

around the cities of Yerevan and Vagarshapat (Echmiadzin) that embraced the

county of New-Bayazet as well as the eastern parts of Alexandropol,Yerevan,

Echmiadzin and Sharur-Daralaghez counties of the province of Yerevan[1].

Turkey was also given carte blanche to act in Azerbaijan a considerable part

of which including Baku was in the hands of Bolsheviks who at that time opposed

any idea of independent Azerbaijani statehood.

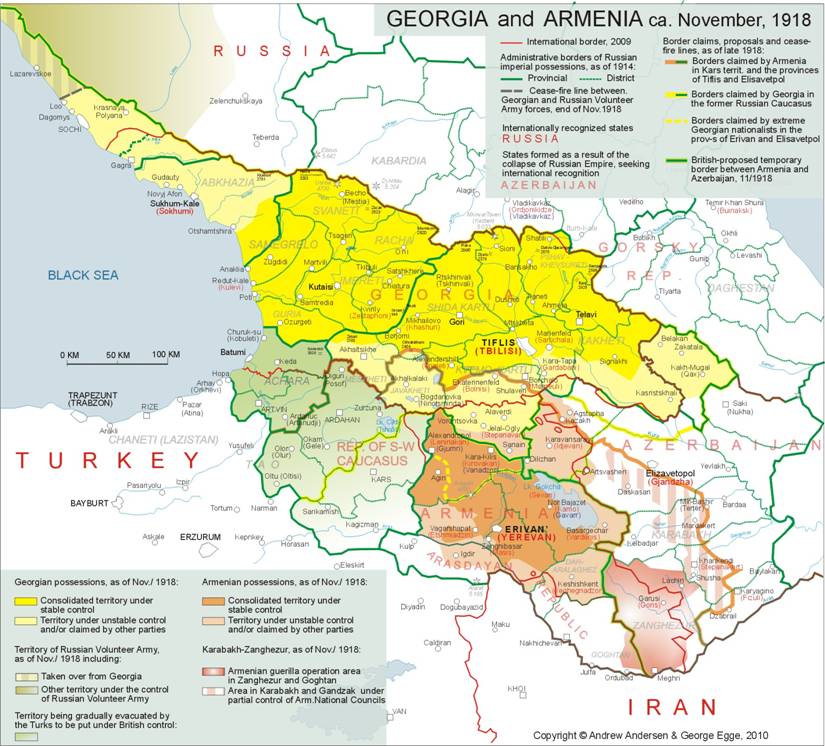

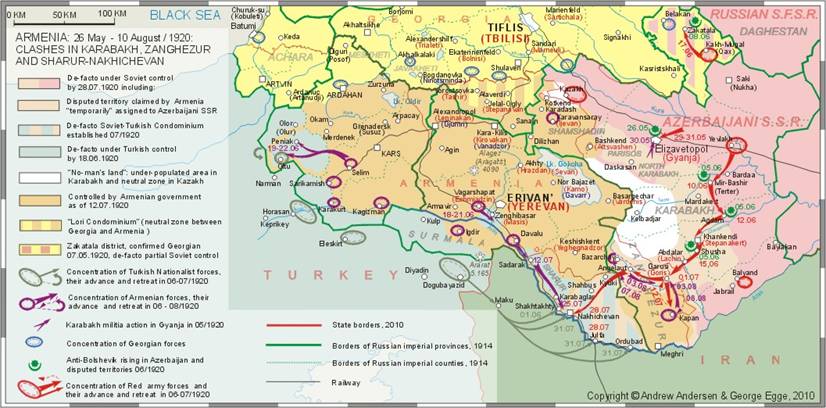

Figure 2.2

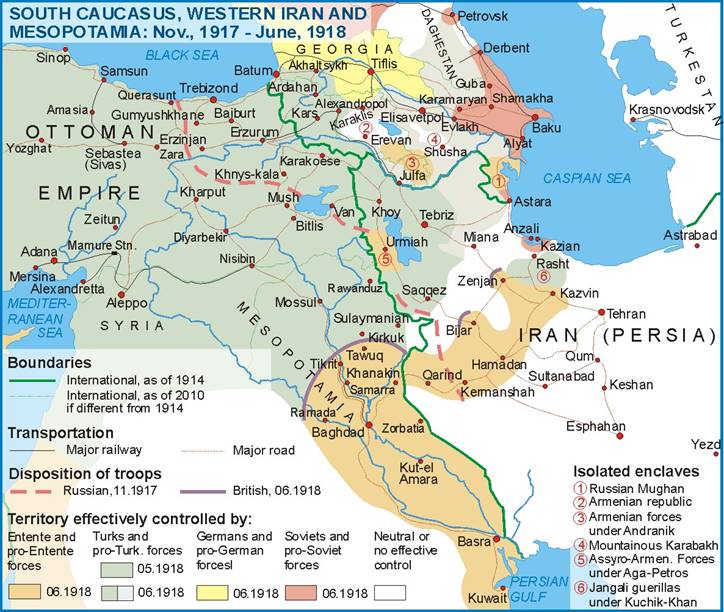

Figure 2.2a By the end of summer 1918, Ottoman troops

supported by the mainly Tatar “Army of Islam” took over most of the territory

of what could be considered the former Russian Azerbaijan (the provinces of

Baku and Elizavetpol) and marched into Baku where they massacred between 10

and 30,000 Armenians still residing in the city[2].

In late September, 1918, once-cosmopolitan Meanwhile, contrary to the provisions of

the Treaty of Batum, some Armenian troops under general Andranik continued

guerrilla operations against the Turks from the mountainous area of

Zanghezur, thus having formed another de-facto independent Armenian

quasi-state formation there. At the same time, the Armenian-inhabited

part of Karabakh (including its northern areas) enjoyed relative peace in

August and September of 1918 administered by the People’s Government of Karabakh elected by the First Assembly of

Karabakh Armenians[3].

It was only at the very end of September when Shusha, the capital of

Mountainous Karabakh did submit to the Ottoman-Azerbaijani conquest[4].

As for the rural areas of Mountainous Karabakh are concerned, they formed

several enclaves (Khachen, Jraberd, Varanda, Dizak and a few smaller areas of

Northern Karabakh) that were kept under control of local Armenian warlords

until the very end of the World War[5].

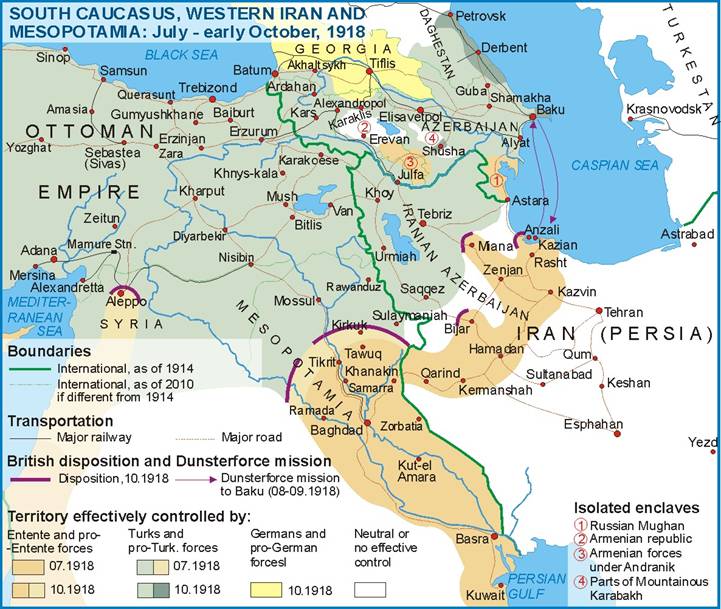

Figure 2.2b The surrender of Ottoman Turkey on October 30,

1918, and the subsequent end of World War I in November, 1918, resulted in

evacuation of regular troops of the defeated Central Powers from most of the

Caucasus. However, in accordance with Clause 11 of the Mudros Armistice, the

Turkish troops were allowed to occupy the territories of Batum and Kars left

to the ottoman Empire by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk for an indefinite period

of time until and if ”demanded by the Allies after investigation”[6].

At the same time, the Ottoman Ministry of War issued a special directive

according to which thousands of Turkish officers and soldiers were

unofficially left at the service of the republics of Azerbaijan and North Caucasus

in order to keep them within the sphere of Turkish influence[7]. The future of the self-proclaimed republics

of the South Caucasus however, still remained unclear. The treaties of

Brest-Litovsk and Batum were now both null and void thus allowing Armenia and

Georgia to claim the territories previously lost to the Turks but at the same

time, the recognition of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan was withdrawn as

well[8].

The victorious allies initially tended to consider them as temporarily

breakaway Russian territories but the development of the crisis situation in

and around revolutionary Russia in combination with current inability of the

two fallen empires to satisfy their ambitions in the region, gave the new

nations of the South Caucasus a historical chance to establish/recover[9]

their statehood, and as early as in November 17 the allied command in the

Middle East declared that the representatives of Britain, France and the USA

were ready to establish relations with the de-facto governments of Armenia, Azerbaijan

and Georgia[10].

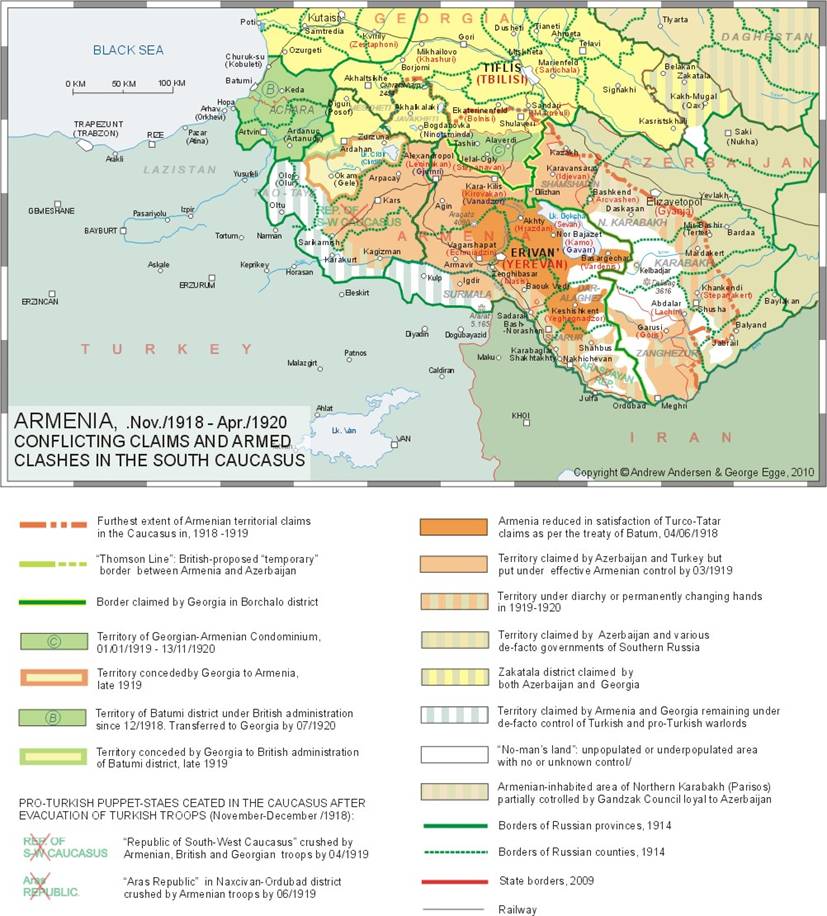

Besides the problem of diplomatic recognition accompanied by a variety of

other political as well as economic problems, the period of nation-building

in the South Caucasus was marked by territorial disputes and conflicting

claims, that caused serious troubles for all the nations of the region not

excluding Armenia. As of late October, 1918, the Democratic

Republic of Armenia claimed a considerable part of the former Russian South

Caucasus that included the whole of the province of Erevan, all the four

districts of Kars territory, the counties of Akhalkalaki and Borchalo in the

province of Tiflis and in the province of Elizavetpol – the whole Zanghezur

county as well as mountainous parts of the counties of Elizavetpol,

Javanshir, Karyaghino, Shusha[11]

and Kazakh (see Maps 2

and 3). The above claims

were based on the principle of historical belonging of the above territories

to ancient and early mediaeval Armenian states and on ethnic principle, since

most of the territories in question had either Armenian majority or at least

heavy presence of Armenians. Some of the Armenian elites also considered

laying claims to the territory of Batum, so that landlocked Armenia could

gain access to the sea. The Armenian territorial claims were in

sharp conflict with the aspirations of Azerbaijan and Georgia, not to mention

Turkey. The political elites of Azerbaijan were also basing their claims on

both historical and ethnic principles. In terms of history they tended to

disregard the earlier periods when the South Caucasus was dominated by

Armenian and Georgian states but put an emphasis on the period that started

from the late 14th century when the area was turned into the realm

of Kara-Koyunlu and later of the Safavids both of whom they considered to be

the fore-founders of modern Azerbaijan. Following the above principle, there

was no place left for Armenia on the map at all. Even the tiny enclave left

for the Armenians as per the Treaty of Batum, was according to the leadership

of Azerbaijan inalienable part of their new-born country. As for the ethnic

composition of the territory claimed by Armenia in the Caucasus, it would

hardly be an exaggeration to say that most of it was also marked by heavy or

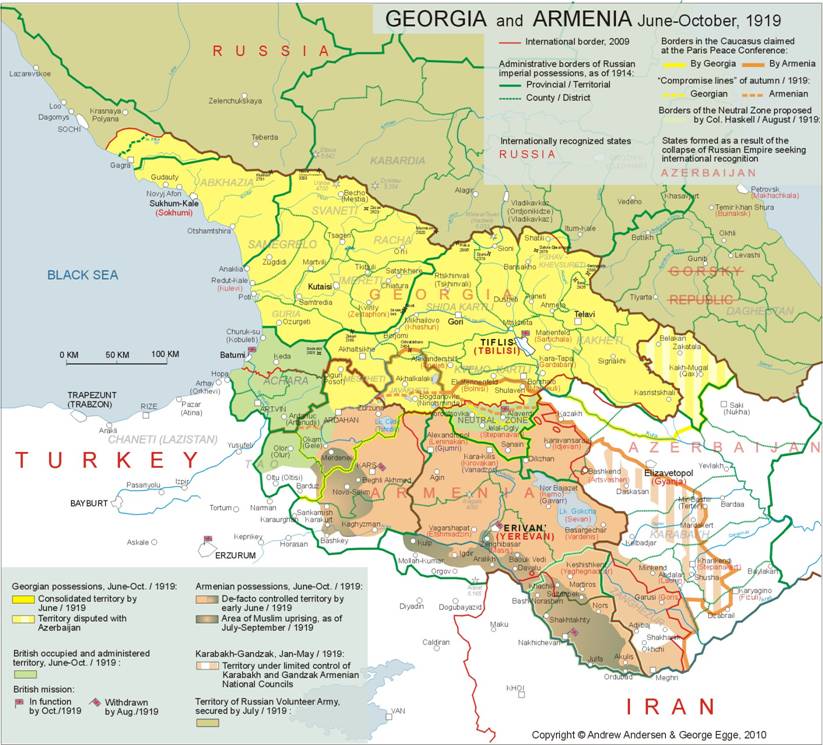

significant presence of Turco-Tatars and other Muslim groups. Map 2. Click on the map for better resolution Map 3. Click on the map for better resolution Although resting on more or less equally

logical foundations[12]

the above mentioned territorial disputes in the South Caucasus led to a

series of clashes and wars in 1918-1921. As a result, mutual dislike

intensified in the area and the dragon’s teeth of a number of modern regional

conflicts were sawn. The

Conflict around the South-West Caucasian Republic, 05/11/1918 – 22/04/1919 On the 11th of November, 1918

Jevad Pasha received a communiqué from

British Commander in Chief in the Mediterranean, Vice Admiral Gough-Calthorpe

containing an unequivocal demand of the Supreme Allied War Council to clear

completely all the occupied territories of the Caucasus including the

territories of Kars and Batum where some 50 000 Turkish troops were still

stationed after Mudros[13].

The Ottoman reaction was slow and the tactics of delaying was adopted in

order to postpone evacuation of the above territories. After long

negotiations the Turkidh 9th Army under Shevki Pasha was allowed

to stay in Kars up until January 25, 1919 whereas the transfer of the Kars territory

to Armenia was to begin no later than January 15[14]. While formally accepting the demands of the

victorious allies the Turks took certain measures to keep Kars and some other

territories around it within the sphere of Turkish dominance just like it was

dome in Azerbaijan, Daghestan and other areas they had taken over by the end

of summer, 1918 and were to leave after Mudros. Not only numerous Turkish

officers were left behind as instruvctors but the whole units of the 9th

Army were only cosmetically re-uniformed in order to look more like local

militia and in order to prevent Armenian and Georgian takeover in the

territories of Kars and Batum[15].

The evacuating Ottoman administration was also quite successful in the

establishment of a few puppet governments in the former Russian areas of the

South-Western Caucasus that would attempt to stay in close connection and

possibly even alliance with Turkey. One of the new state formations of that

kind was the South-West Caucasian Republic (SWCR) created in Kars shortly

after Mudros. The pro-Turkish government of Fakhreddin (Erdoghan) Pirioglu

formed in Kars on November 5, 1918, claimed effective control not only over

the four districts of Kars territory but also over all the former Russian

territories annexed by Turkey as per the Treaty of Batum including but not

limiting to Nakhichevan and Alexandropol counties of the province of Erevan,

the counties of Akhaltsikhe and Akhalkalaki in the province of Tiflis and

Batum territory (former Batum district of the province of Kutais) (see Map 3)[16]. The Kars government rejected both Armenian

and Georgian authority and rather effectively exploited the principle of

self-determination declared by the USA, Britain and France. Indeed the SWCR

enjoyed some favor on behalf of the British mission in the Caucasus[17].

The British troops even blocked the roads leading to Kars from the province

of Erevan and prevented some 100 000 Armenian refugees from returning to

their homes[18]. At

the same time the Azerbaijani government of Khan Khoisky tried to urge

British approval for at least temporary annexation of the SWCR territory by

the Republic of Azerbaijan[19].

The

sympathies of allies turned around in early February of the year 1919 when

the paramilitary forces of SWCR under the command Server Beg invaded

Georgian-controlled counties of Akhaltsikhe and Akhalkalaki in order to

expand the Kars-controlled territory[20].

Following the counter-offensive of the Georgian army of early April, 1919 the

British troops already stationed in the province of Erevan entered Kars on

April 6-9. On April 10, 1919, the SWCR leaders were arrested and deported

whilenine days later, the city of Kars was handed to the Armenian governor.

By April 22, the Georgians completely crushed the resistance of Server Beg’s

paramilitaries in the county of Akhaltsikhe and the district of Ardahan and

put both counties under their control. The South-West Caucasian Republic was

abolished, and the districts of Kars and Sarykamysh were annexed by the

Democratic Republic of Armenia while the county of Ardahan was taken over by

Georgia[21]. The

British command in the Caucasus did not allow either Georgian or Armenian

troops to enter the territory that included the district of Oltu (Olti) which

was claimed by both nations and the sector of Karaqurt claimed by Armenia

leaving it in the hands of local Muslim chieftains until it was once again

taken over by the Turks during the Turkish-Armenian war of late 1920. A few

months later Georgia conceded part of the district of Ardahan (Okam sector

and most of Chyldyr sector) to Armenia[22]

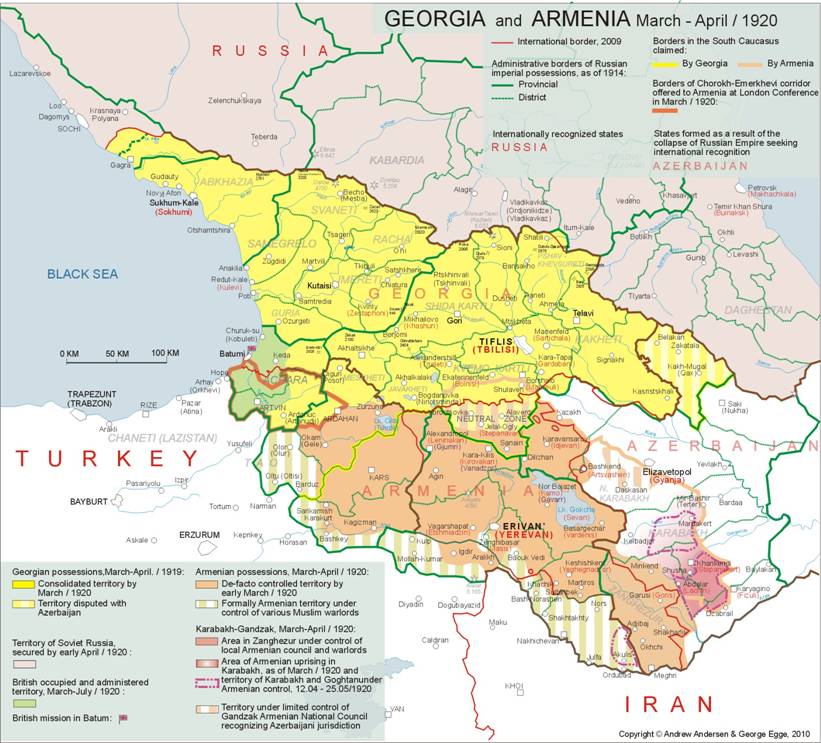

(see Maps 2 and 4). Armenia

versus Azerbaijan: The British Mediation Failure Mutual territorial claims of Armenia and

Azerbaijan led to the series of brutal wars accompanied by periodical

massacres of civilians in the disputed area that included Kazakh-Shamshadin, Nakhichevan,

Zanghezur and Karabakh. The first hostilities in the above and other areas

with mixed population occurred as early as the spring of 1918, when the South

Caucasus was invaded by the Ottoman armies to end in 1921 only.

The government of Armenia was not prepared

to drop their claims to Kazakh-Shamshadin, Zanghezur and Karabakh while

Azerbaijan was not accepting the idea of Armenian control over Surmala and

Nakhichevan - Ordubad. To make things worse, the masses of population of a

number of territories assigned to Armenia and Azerbaijan were not prepared to

consider themselves a part of the republics to which they were assigned by

Thomson. Thus the fragile peace with an unresolved territorial dispute at its

background could not last for too long, and the series of Azeri-Armenian wars

broke out both in the provinces of Erevan and Elizavetpol as early as at the

end of 1918. Contrary to Armenian aspirations and hopes

for special treatment following their uninterrupted loyalty to the Allies

throughout the whole of the Great War, the British Command in the South

Caucasus decided in the late fall of 1918, to leave the Karabakh-Zanghezur

area under the jurisdiction of oil-rich Azerbaijan at least until the moment

when the final delimitation agreement would be reached at the Paris peace

Conference[24]. That

led to a fragile diarchy in the Armenian-populated parts of Karabakh where

the Erevan-oriented People’s Government in Shusha that had been running the area

since July 1918, was forced to share its power with the British appointee Dr.

Khosrow Bek Sultanov who was given authority by Thomson to run a considerable

part (4 of 8 counties) of the province of Elisavetpol including Mountaineous

Karabakh and Zanghezur[25](see

Map.4). The following 8 months in Mountainous

Karabakh were marked with the total failure of cooperation between

consecutive Armenian Assemblies and Sultanov as well as with the non-stopping

ethnic conflicts that led to armed clashes between local Armenian

self-defense forces and the regular army of Azerbaijan that included some

3000 Turkish troops still stationed in the area[26]

and were assisted by armed militias recruited from Tatar and Kurd nomads of

western Karabakh. At the same period of time, almost the

whole county of Zanghezur was under stable control of Armenian military units

and formations of general Andranik who being formally disloyal to the

government in Erevan, felt quite free to act independently and crashed all

attempts of the regular armies of Turkey and Azerbaijan to put Zanghezur

under their control. Following the armistice of Mudros

and an appeal from the Armenian-controlled part of Karabakh, Andranik sent

his “Special Striking Division” out toward Shusha on November 29, 1918. After

three days of fierce fighting against Azeri-Kurd irregulars for a narrow

strip of land separating Armenian-controlled parts of Zanghezur and Karabakh

Andranik’s men had the way to the heartland of Karabakh unobstructed.

However, an urgent message from Major General Thomson received by Andranik on

December 03 contained an unequivocal order to move back to Zanghezur and to

refrain from taking any disputed territory by force until the decision of the

peace conference[27].

Andranik submitted and stepped down as a commander of the Armenian forces in

Zanghezur while Muslim militias wiped out all remaining Armenian settlements

connecting Karabakh with Zanghezur[28]. Despite repeatedly expressed aspirations of

the Karabakh Armenians for unification with Armenia, the government of the

First Republic in Erevan was reluctant to insist on immediate annexation of

Mountainous Karabakh rather leaning towards the creation of a buffer state in

the areas with mixed population east of Zanghezur[29].

Finally, on August 22, 1919, after long negotiations, an agreement was

reached in Shusha between the Seventh Assembly of Karabakh

(Armenian-dominated) and Sultanov in accordance with which Mountainous

Karabakh (but not Zanghezur) was to remain temporarily within Azerbaijan

until the final resolution of the conflict at the Paris Peace Conference[30].

In the county of Zanghezur that in

accordance with the initial plans of Thomson was to be included into the

special governorate of Karabakh run by Khosrow Bek Sultanov, the situation

was different. After disappointed with the British Major General Andranik

stepped down as a commander of all Armenian forces in Zanghezur on March 22,

1919[31],

local Armenian field commanders refused to submit to the British dictate.

After being pressed by British representatives they expressed their

preparedness to fight to the end against any power that would attempt to

submit them to Azerbaijan including Britain and France, Thomson agreed to

exclude Zanghezur from the list of ethnically diverse counties “temporarily”

granted to Azerbaijan. The government of Azerbaijani Republic was informed on

that concession on May 29, 1919[32].

By that time the Armenian militias of Zanghezur destroyed rebellious Muslim

communities in the central areas of the county and expelled them to the

periphery[33]. In addition to the five major historical

districts of Karabakh (Gyulistan, Khachen, Jraberd, Varanda and Dizak) there

is another area sometimes included into the disputed historical province.

That is the mountainous part of the Elizavetpol (Gyanja) county. The smaller

part of this area The smaller part of the described area south of the village

of Chaykend and north of Inja river (which also served as a border between

the counties of Elizavetpol and Javanshir) that embraced a group of ethnic

Armenian settlements forming a triangle with apexes in the villages of

Karachinar, Enghikend and Gyulistan, is the continuation of historical

Gyulistan whereas the remaining part of that mountainous territory

predominantly Armenian-inhabited until 1989, is referred to by various

historical geographers and politicians as Northern Karabakh, North-Western

Karabakh or Parisos. The Armenian communities of Parisos were not represented

at the Karabakh Assemblies (unlike those of Gyulistan). Instead they were

administered by the Armenian National

Council of Gandzak in Gyanja that in turn, demonstrated loyalty to Turkey

during Ottoman occupation and later – to Azerbaijan to the extent that two of

the Council members were selected to represent the area in the Azerbaijani

Parliament[34]. One should add to the above that there was

a considerable no-man’s land between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the upper flow

of the river Terter and around the mountains of Omar, Gyamysh, Jinaldagh,

Delidagh, Klyshdagh and Sarychly. It embraced south-western part of the

county of Gyanja, eastern part of Javanshir county and northernmost

Zanghezur. Having no infrastructure that mountainous area had almost no

population except a few nomadic tribes (predominantly Kurds relatively loyal

to Azerbaijan) that used to be present in the area in summer only and moved

down to the lower Karabakh in winter together with their livestock. During

the period between the fall of 1918 and the spring of 1920, the

above-described area was claimed by both Azerbaijan and Armenia but hardly

any of the conflicting parties could boast an effective control over it until

the Soviet takeover in May, 1920. Map 4. Click on the map for better resolution

The delay proved crucial. By that moment

the pan-Turanist “Arasdayan Republic” was proclaimed in the disputed area[36]

and local anti-Armenian forces were armed and organized well enough to repel

or at least slow down possible Armenian expansion. The eruption of a new war

was this time prevented through Allied mediation and establishment of a

special British governorship on January 26, 1919[37].

The new British protectorate embraced most of the county of Nakhichevan

(excluding the mountainous area) all of Sharur and even some 30% of the

county of Erevan up till the river of Vedichay[38].

Although the area was excluded from the Armenian republic, the British

governorship put an end to the “Arasdayan Republic”[39]

leaving most of the real administrative power to Japhar-Kouli Khan of

Nakhichevan with the police functions performed by a small British

contingent. The spring of 1919 saw the reversal of

British sympathies for Muslim aspirations in the some areas of the South

Caucasus. The analysis of the reasons of such a reversal would go far beyond

the framework of this article. Here we can only mention that after a series

of talks performed by British emissaries in Tiflis, Erevan, Baku and

Nakhichevan the allied governorship was abolished and the British units

stationed in the area were to be replaced Armenian troops under General Dro

(Drastamat Kanayan). On May 16, 1919, the whole of Sharur, Nakhichevan and

Goghtan were put under formal Armenian control and By June 7 the last British

units left the disputed area. Thus by the beginning of the summer of

1919, the First Armenian Republic managed to put under her formal control

most o the territory that could be called “the former Russian Armenia” with

the exception of the Mountainous Karabakh (see Map 5). The temporary borders

of Armenia were reflected on the map prepared for presentation at the Peace

Conference in Paris by British Brigadier General William Henry Beach.

According to that map Armenia included most of the Kars territory as well as

all of the province of Erevan (including Sharur, Nakhichevan and Goghtan) and

the county of Zanghezur[40].

The map of Beach is a document of specially interest keeping in mind that

until April, 1919, its author (the head of the

British military intelligence in the Caucasus) was known as a

strong advocate of the inclusion of the counties of Zanghezur and Nakhichevan

into Azerbaijan[41]. Nevertheless, in the early summer of 1919

neither Armenian, nor Azerbaijani governments and elites believed that the

territorial dispute was over. The events that followed confirmed that the

status quo in the South Caucasus was quite fragile. Muslim

Uprisings in Kars and Sharur-Nakhichevan and the failure of American Mediation,

07/1919 – 10/1919 The fragile status quo followed by the

abolition of South-West Caucasian Republic (SWCR) and Arasdayan Republic as

well as the establishment of Armenian administration in Kars territory and

Nakhichevan county in April-May, 1919, did not last long. Extensive

anti-Armenian campaign based on pan-Islamic and pan-Turanic agenda launched

by numerous emissaries of Turkish nationalists and Azerbaijani government in

combination with massive arms deliveries to the areas of Muslim majority from

Erzurum through Barduz and from Baku via Northern Persia, triggered a series

of well-organized uprisings against Armenian rule in July, 1919, in the

province of Erevan (in the counties of Surmala, Sharur, Nakhichevan and

Erevan[42]) and

all over the Kars territory[43]. By the beginning of August, Armenian

administration was expelled from the Araxes valley between Ordubad and Davalu

in the province of Erevan[44],

and most of Nakhichevan county was lost except the eastern foothills. The

area of Sharur-Nakhichevan taken over by the Muslim rebels commanded by Samed

Bey Jamalinsky was hoisting Azerbaijani and Turkish flags, and the majority

of local Armenians, who still resided there in June, 1919, were either wiped

out or forced to flee[45].

In Kars territory fierce fighting that

occurred throughout July and August around Karaurghan, Karakurt and Bashkey

west of Kaghyzman[46]

and in the area of Merdenek - Novo-Selim - Beghli Akhmed west of Kars,

resulted in a series of Armenian successes against Kurdish and Turco-Tatar

tribes enforced by regular Turkish troops and often commanded by Turkish

officers[47]. By

September, 1919, the Armenian control was re-established in most of the Kars

territory excluding the Georgian-controlled northern sector of Ardahan

district and the British-protected district of Olti still controlled by the

Muslim militiamen of Ayyub-Khan and Server Beg[48].

At the same time, in Surmala Armenian control remained limited to the plain

of Ararat while the strategic heights dominating the areas around Kulp, Orgov

and Aralikh remained firmly in the hands of Kurdo-Tatars[49]. All the above events occurred against the

background of British withdrawal from the South Caucasus that started with

the evacuation of Baku between August 15 and 23, 1919, and by September 11,

there was only a small British contingent remaining in Batum still

administered by the United Kingdom[50]. Meanwhile, a US Colonel William Haskell who

arrived to the Caucasus as an Allied High Commissioner for Armenia in August,

1919, made an attempt to arrange a truce between the conflicting parties.

After having met with Armenian and Azerbaijani officials, Haskell proposed a

creation of a Neutral Zone between the two “sister republics” that would

encompass the counties of Nakhichevan and Sharur-Daralaghez and be

administered by a US governor. The American proposal was met with reserved

satisfaction in Azerbaijan and indignation in Armenia due to the fact that both

governments clearly understood that the fulfillment of Haskell’s proposal

would be another step towards absorption by Azerbaijan of the territory that

was considered to be inalienable part of Armenia in Erevan and was referred

to as “South-Western Azerbaijan” in Baku[51].

The proposed Neutral Zone would also cut Zanghezur off the rest of Armenia

thus making it more vulnerable to the Azerbaijani expansion. By the end of

October, 1919, it became clear that all efforts of Haskell’s mission ended up

in vain. No agreement was

reached on the disputed territory most of which remained under de-facto

control of Azerbaijan and Turkey until March, 1920. Azerbaijani

invasion of Zanghezur, the Truce and the Fall of Goghtan, 11-12/1919 Within a week and a half after the invasion

began, Armenian forces under Njdeh took action against the armed Muslim

villages that reportedly supported the invaders in Meghri and Ghapan cantons

in the very the centre of Zanghezur. That operation resulted in the capture

of Kajaran, Shabadin, Okhchi, Piroudan and a few other Muslim villages its

defendants wiped out and inhabitants expelled, and in re-opening the mountain

pass to the still fighting northern Goghtan in the foothills of Ordubad

sector of Nakhichevan county. In the middle of November US and British

representatives in the Caucasus Sir Oliver Wardrop (British Chief

Commissioner since July, 1919) and Colonel James Rhea addressed the

governments of Azerbaijan and Armenia and demanded that the undeclared war

between the two republics should be stopped immediately. The

Armenian-Azerbaijani talks started on November 20 in Tiflis (Georgia) and

came to an end three days later with no breakthrough. On November 23, 1919 the Prime Ministers of

the two countries (Alexandre Khatisian and Nasib Bek Usubbekov) signed an

agreement that was in fact nothing more but a declaration of intent[54].

Meanwhile, military operations and ethnic cleansing went on in Zanghezur and

Goghtan. Goghtan, a very small Armenian historical

province with its centre in Akulis in size and location roughly corresponding

to Ordubad sector, managed to withstand the Ottoman invasion of 1918 and

attempted to survive the Muslim uprising of July-August of 1919 through the

declaration of its loyalty to the de-facto authorities in Nakhichevan and

Ordubad. Nevertheless, most of the southern villages of Goghtan were

devastated by the rebels. Facing the massacre, the northern villages took up

arms to defend themselves and asked Erevan for help. The Armenian government

could sent only a small relief detachment that reached Goghtan only in

October to help local militiamen to hold against the offensive of Ordubad

militiamen and regular Turkish troops. In November Lieutenant Colonel Njdeh

was planning to lift the siege of Akulis and launch an offensive in the

direction of Ordubad in order to secure the flank of Zanghezur. However he

was ordered to postpone the Goghtan operation until his troops would finish

the pacification of the last Muslim communities in the Barkushat mountains.

The hero of Zanghezur had to obey orders but by the time when the last Muslim

village of Ajibaj in the heart of Zanghezur was put to sword and fire it was

too late to save what was left of Goghtan. By December 18, 1919 the

resistance of Goghtan was crushed and a week later the last surviving

Armenians left the area for Zanghezur. That marked the completion of ethnic

cleansing both in Zanghezur and in the southernmost sector of Nakhichevan[55]. Map 5. Click on the map for better resolution

The Shosh resolution signaled the

escalation of tension in Mountainous Karabakh. Less than a week after its

adoption, additional units of the Azerbaijani Army prepared to enter the

region while in the villages of Varanda, Dizaq, Khachen, Jraberd and

Gyulistan Armenian self-defense units were preparing for an armed uprising

encouraged by the envoys from Armenia[61]. The Armenian uprising in Karabakh that

started on March 23, 1920, was rather a failure due to its poor organization

and even poorer coordination with Erevan and Zanghezur. Initial success that

took place in Askeran where the rebels sealed the Askeran pass making it

impossible for Azerbaijani reinforcements to advance to Shusha and in Dizaq

where the stable access to Zanghezur was secured came to naught after the

fiasco of the rebels in the cities of Shusha and Khankendy. At the same time,

no expected relief forces came from Zanghezur due to the physical absence of

General Dro (the commander of regular Armenian expeditionary forces that had

been prepared to advance into Karabakh) and because the fighters of the

Zanghezur warlord Gareghin Njdeh got stuck in their abortive attempt to

re-conquer Goghtan (March 21-25, 1920) and later (March 25-30) in the repel

of Azerbaijani invasion from Jabrail[62]. Until April 03 badly outnumbered Armenian

defenders of the Askeran pass were repelling non-stopping attacks of the

Azerbaijani army under the command of General Samed Bek Mekhmandarov.

However, the insufficiency of the Armenian forces combined with the lack of

ammunition and artillery on their side, made the fall of Askeran inevitable,

and on April 4 thousands of Azerbaijani troops decimated the last rebels

blocking their way into the heart of Karabakh and poured into the area down

the road towards Khankendy and Shusha where most of the local Armenians had

been already massacred by the victorious Azerbaijani garrisons and armed

Muslim mobs. The Christian part of Shusha (de-facto capital of Mountainous

Karabakh) was completely destroyed and burnt down and so were dozens of

Armenian villages around it[63].

Five days later the rebels counter-attacked forcing Azerbaijani forces to

draw back. However hankendy and the ruins of Shusha still remained in

Azerbaijani hands thus cutting the rebel-controlled area into two isolated

enclaves (see Map 6), Simultaneously, armed clashes involving

regular units of Armenian and Azerbaijani armies also resumed in Kazakh and

Nakhichevan counties thus allowing some researchers to define the Karabakh

uprising as a full-scale Armeno-Azerbaijani war. It was not until April 13, 1920

when regular Armenian troops under General Dro (Drastamat Kanayan) finally

entered Karabakh through Zanghezur and put Dizaq and rural Varanda under

stable Armenian control (see Map 6). In the Armenian-dominated parts of

Karabakh the Directorate was formed

that became de-facto government of the region. On April 22 the Ninth Assembly of

Mountainous Karabakh[64]

was summoned in Taghavard to reaffirm the union of Mountainous Karabakh with

Armenia and authorize Dro to take “whatever action necessary to

liberate the district”[65].

Meanwhile, keeping most of its armed forces in the areas disputed with

Armenia, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was left defenseless against the

Red army that concentrated on her northern frontier[66].

On April 27, 1920, Soviet Russian 11th Army invaded Azerbaijan. Less than 24

hours the First Azerbaijani Republic collapsed as a result of a bloodless

coup in Baku, and on April 29 Soviet occupants and local communists

proclaimed Azerbaijani Soviet Republic thus signalling the beginning of the

Soviet era in the South Caucasus. The atmosphere of political vacuum that

lasted another two weeks till the moment when the first units of the 11th

Army stated their advance into Mountainous Karabakh[67],

was quite favorable for Dro to take over Shusha, Khankendy and Askeran and

secure the unification of the region with the Armenian republic. However,

Armenian commander did not issue the order to attack, and the last chance for

complete liberation of the Mountainous Karabakh was lost. The war between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the spring of 1920 ended

up with at least partial Armenian victory. However, it completely destroyed

the reputation of both nations in the West as well as the confidence of their

ability to live in peace with each other and their neighbors[68].

Map 6. Click on the map for better resolution North-Western

Karabakh/Parisos: “the Forgotten Armenia”? During the period preceding the Karabakh

uprising the Armenian communities of North-Western Karabakh/Parisos

subordinate to the Armenian National

Council of Gandzak (see Map 6 and pp. 15-16 for the description of the

area) were consistent in keeping their loyalty towards Azerbaijani republic.

The rural Armenian communities scattered in the mountainous area of the

county of Elizavetpol (Gyanja) from Chaykend to Chardakhly were mostly

well-armed but tended to avoid any forms of inter- racial or inter-religious

violence were armed for self-defence. In January 1920 they expelled and

labeled as instigators the envoys from Armenia who came to the area in an

attempt to organize an anti-Azerbaijani uprising[69],

and as soon as the first armed clashes occurred in Karabakh, both the Council

of Gandzak and all the villages of the county except those south of Chaykend

(Northern Gyulistan) vocally distanced themselves from the Karabakh rebels[70]. The loyalty to Azerbaijan, however, did not

spare the Armenians of Gandzak/Parisos from paying for their brethren’s

revolt in Karabakh. The rural Armenian enclaves were surrounded by

Azerbaijani militia and gendarmerie and ordered to disarm. Most of the

villages that complied were looted and burned while those that did not found

themselves under siege. Some of the villages were forced to pay “protection

taxes”. The spillover of the Karabakh violence into North-Western

Karabakh/Parisos resulted in thousands of deaths and in exodus of many rural

Armenian communities into the Armenian quarter of Elizavetpol

(Gyanja/Gandzak) and the German colony of Elenendorf[71]. The Evacuation of the British troops from

the South Caucasus that started in summer of 1919 and finished in the middle of

summer of the year 1920[72] and

the Soviet blitzkrieg of April, 1920,

against Azerbaijan followed by the rapid Sovietisation of that country

performed with the help of Turkish Nationalists[73] signalled the

beginning of an undeclared Soviet-Armenian war that lasted more than FIVE

months and resulted in the loss of most of the disputed territories[74]. The first decade of May 1920 was marked by

the Soviet 11th Army advance toward Karabakh, Gandzak and Kazakh

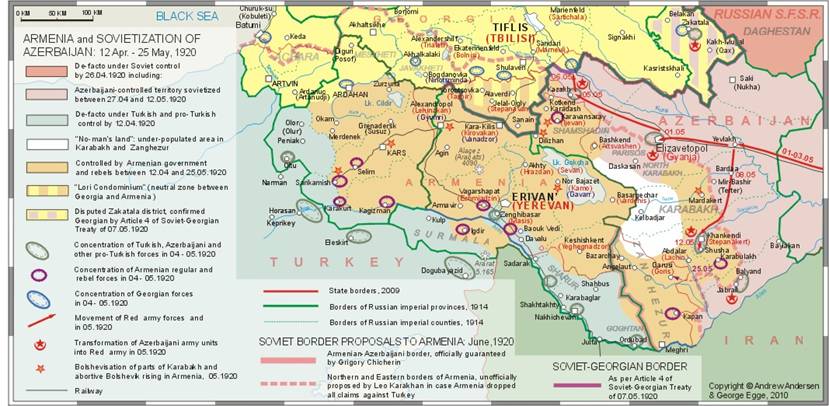

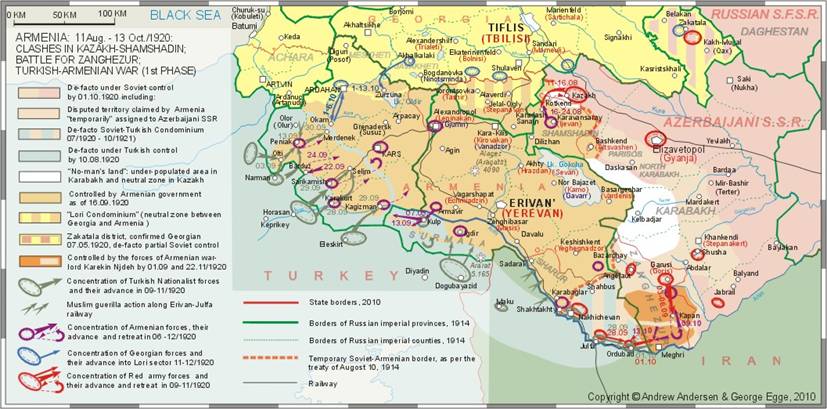

(see Map 7). In

view of the approaching Soviet troops most of the units of the Azerbaijani

army as well as the members of the Azerbaijani administration quickly

transformed into the Red Army and Soviet bureaucracy swearing allegiance to

the new dominant power of the region[75].

Most of the Turkish officers stationed in Azerbaijan also went to Soviet

service including Nuri Pasha[76].

On May 12 the first Soviet detachments reached Shusha having the directive to

take over the whole of Mountainous Karabakh, Zanghezur and Sharur-Nakhichevan[77].

A week later after a few skirmishes Armenian General Draw whose troops still

controlled Dizaq and most of Varanda was given an ultimatum to withdraw. By

that time most of the Armenian militias in Jraberd, Khachen and Gyulistan

became rather pro-Soviet under the influence of Bolshevik propaganda. As a

result, all the Armenian officers and instructors there who refused to surrender

to the Soviets were killed, arrested or expelled and the whole

Armenian-controlled part of Karabakh to the north of Soviet-dominated

Shusha-Khankendy-Askeran corridor was lost to the Soviets. In view of the

loss of the above territory, as well as the change in sentiment even among

Varanda and Dizaq Armenians and bad communication with Erevan, General Dro

and his Staff decided to comply with the Soviet demands, and on May 25-26 all

regular Armenian forces still in Karabakh withdrew to Zanghezur. After the

evacuation the evacuation of the Armenian troops of Dro and Njdeh, only few

isolated groups of Armenian fighters kept conducting guerilla operations in

the mountains of Karabakh[78]. However, since the end of May 1920,

Mountainous Karabakh now united under the Soviet red banners was administered

by the two Revkoms: Muslim-dominated one in Shusha and Armenian-dominatred in

the village of Taghavard[79]. Map 7. Click on the map for better resolution The situation in the north-western section

of Armeno-Azerbaijani frontier was even more complicated (see Map 7). The county of Kazakh faced open Red Army incursions

into Armenian-controlled territory in attempts to support the abortive

communist uprising of May 1920[80].

The attempted communist coup in Armenia (May 10-30, 1920) was unsuccessful.

Although Armenian communists managed to take over the towns of Alexandropol,

Kars, Sarakykamysh, as well as several villages in disputed Kazakh-Shamshadin

area, the uprising was put down by the government troops and militias in less

than a month. However, it undermined the efforts of Armenia to withstand

Soviet invasion and led to the series of military defeats in

Kazakh-Shamshadin and Karabakh[81]. At the same period of time quite confusing

was the development of events in the county of Elizavetpol (Gyanja/Gandzak).

According to Kadishev, facing little resistance on behalf of disorganized and

demoralized Azerbaijani army Armenian troops and guerillas took over all of

the mountainous sector of the county reaching the outskirts of Gyanja[82].

The situation was further complicated by some facts of joint Soviet-Armenian

operations against Azerbaijani rebels during an abortive anti-Soviet uprising

that occurred in and around Gyanja at the end of May 1920[83].

As of today, it is not very easy to define where exactly stretched the limits

of de-facto Armenian control in Kazakh-Shamshadin and Gandzak-Parisos in late

spring of 1920. Some official documents of that period of time, define some

portions of that border quite clearly making modern researchers quite

confused. As an example, one can adduce an excerpt from the text of the

Soviet-Georgian Treaty of Moscow signed on May 07, 1920, according to which

the border between Georgia and Soviet Azerbaijan “…goes along the eastern

border of Zakatala district to the south until it touches the border of

Armenia”[84]. The

above excerpt clearly states that Armenian territory near the city of Gyanja

at least for a while could have stretched until the river of Kura. Soviet-Armenian

Negotiations in Moscow and the Summer Campaigns in Armenia, 05/1920 - 08/1920 The first sessions

of negotiations seemed to be moderately favorable to the Armenians. Chicherin

assured Shant that the Soviet Russia had no plans to invade Armenia or to

establish a Soviet regime in that country.

Chicherin even offered that Soviet Russia would take a role of a mediator in Armenian

territorial dispute with the Turks keeping in mind close cooperation between

Moscow and Turkish Nationalist de-facto government of Kemal Ataturk. The

Armenians were promised a part of Western (Turkish) Armenia roughly

corresponding with the initial proposal by Berthelot

(see above)[86].

As for the border conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan the initial Soviet

proposal was to leave Zanghezur and Sharur-Nakhichevan with Armenia while

declaring Karabakh a disputed territory the future of which would be defined

by plebiscite[87].

One should keep in mind here that Chicherin "graciously" offered

the Armenians to keep only those territories that were not yet sovietized. As

will be mentioned below, the format of Soviet proposals kept changing while

the Red Army was taking over new Armenian-claimed territories. The Armenian

delegation was also deeply impressed by the map of a projected Armenian state

that was unofficially demonstrated to them by Karakhan. The map presented by

the Bolshevik diplomat was offering the Armenians not only all the

territories disputed with Azerbaijan (including Mountainous Karabakh) but

also most of Borchalo, the counties of Akhalkalaki and Akhaltsikhe (the

latter never claimed by Armenia) and the Chorokh-Imerkhevi corridor to the

Black sea (see Map 7),

i.e., the territories that the Soviets recognized unequivocally Georgian by

signing the Soviet-Georgian treaty in early May 1920. After being reminded of

that Karakhan replied that the question of Georgian territorial integrity was

“still open”[88],

and significant concession could be given to Armenia if only the Armenians

dropped all or at least most of their aspirations against Turkish territory. During the first

phase of Soviet-Armenian negotiations in Moscow, the 11th Army was busy

putting down anti-Soviet Azerbaijani rebellions in Gyanja, Zakatala and

Agdam-Shusha while Armenian forces were similarly busy with crushing

Bolshevik uprisings in Kars, Sarikamysh, Alexandropol, Nor-Bayazet and

Delizhan and later pacifying rebellious Muslim enclaves in Zenghibazar,

Vedibazar and Peniak[89]

(see Map 8). By mid-June the

Soviet tone at negotiation changed drastically. If earlier the Red Army was

unable to invade Zanghezur-Nakhichevan being tied up with Azerbaijani

uprisings but after the fall of Shusha on June 15, the way to Nakhichevan via

Gerusy (Goris) was open.[90]

Gerusy was taken by the Reds on July 5, and on July 17 the 11th Army

started advance towards Nakhichevan while at the same time the detachments of

Turkish Bayazet division in the amount of 9000 trespassed Iranian territory

north of Khoy and concentrated in Maku. Those Turkish forces under the

command of Jevad Bek were preparing to cross Aras river and enter

Nakhichevan, Julfa and Ordubad from the south-west in order to block further

re-conquest of the Nakhichevan county by Shelkovnikov’s Armenian troops who

had already reached Shakhtakhty by July 25 (see Map 8)[91]. Reflecting rapidly

changing military situation at Soviet-Armenian frontier, Chicherin now

proposed that the new boundary would run along the administrative border

between the old provinces of Erevan and Elizavetpol thus leaving Nakhichevan

to Armenia, Karabakh to Azerbaijan and Zanghezur under "temporary"

Soviet administration as a disputed territory. At some point Influenced by

Sergo Orjonikidze (at that time the Chairman of Kavburo of Russian Communist

Party), Chicherin and Karakhan even proposed to include Sharur-Daralaghez

county into the list of disputed lands. The Armenian delegation was not

prepared to accept permanent loss of Karabakh not to mention the questioning

of the status of Sharur-Daralaghez, and after some fruitless discussions the

talks were suspended[92].

The Red Army was meanwhile fighting Armenian militias in Zanghezur in order

to capture Gerusy[93].

It may be important to mention here that immediately after the Soviet - Armenian

negotiations were interrupted Chicherin started the talks with Foreign

Affairs Commissar of the Turkish Nationalist government in Angora Sami Bey

who arrived in Moscow to arrange joint Soviet - Turkish operations in

Nakhichevan aimed at opening a stable land corridor between Soviet Russia and

Nationalist Turkey[94].

One of the few results of the interrupted Soviet-Armenian negotiations was

the appointment of the lawyer Boris Legran a Soviet plenipotentiary in

Armenia who was supposed according to Chicherin, to finish the negotiations

with the Armenian government directly in Erevan. While Legran’s

mission was slowly making his way to Erevan with prolonged stops at Baku and

Tiflis marked with the exchange of proposals with the Armenian government,

the Soviet-Armenian warfare escalated in Zanghezur. After having taken over

Gerusy in early July 1920, the Soviets established the red terror regime in

the north of Zanghezur and in the middle of the month tried to expand

southwards in an attempt to sovietise the whole county (see Map 8). However, the

first Soviet expedition into the heart of Zanghezur ended up in fiasco by the

beginning of August. Defeated by the militias of Njdeh near Kapan and attacked

by the regulars of Dro in the rear from Angelaut the components of the 11th

Army rapidly evacuated Northern Zanghezur and retreated into Varanda[95].

Following Dro’s ultimatum to clear “all occupied Armenian territories”

including Karabakh, the Soviets started counter-offensive on August 05, and

two days later Gerusy was lost by the Armenians for the second time. The

Shusha-Gerusy-Nakhichevan corridor vbetween Nationalist Turkey and Soviet

Azerbaijan was re-opened, and both Turkish and Soviet officers celebrated

that victory as partners[96]. Meanwhile, in the

county of Nakhichevan Soviet-Turkish and Armenian troops facing each other

halfway between Nakhichevan and Shakhtakhty tried to abstain from open

hostilities following verbal “Gentlmen’s agreement” between Armenian General

Shelkovnikov and “the commander of the united troops of RSFSR and Red

Turkey”, Colonel Tarkhov[97].

On July 28 “Soviet Socialist Republic of Nakhichevan” was proclaimed, and its

“Revolutionary Committee” offered Erevan to recognize the new “independent state”. Map 8. Click on the map for better resolution On August 10 1920, the cease-fire agreement

was signed in Erevan by the representatives of Soviet and Armenian

governments leaving Armenia without most of the disputed territories but

temporarily ending major hostilities along Soviet-Armenian front-lines. As

per the agreement, the temporary south-eastern border of Armenia was defined

as follows: “Shakhtakhty-Khok-Aznaburt-Sultanbek

and further the line northward from Kyuki and westward from Bazarchai

(Bazarkend). And in the county of Kazakh – the line they hjeld on 30 July of

this year. The troops of RSFSR will occupy the disputed districts: Karabakh,

Zanghrzur and Nakhichevan, with the exception of the zone determined by this

treaty for the disposition of the troops of the Republic of Armenia… The

occupation of the disputed territories by the Soviet troops does not

predispose the question about the rights to those territories of the Republic

of Armenia or the Azerbaijan Socialist Soviet Republic. By this temporary

occupation, the RSFSR has in view the creation of favorable conditions for

the peaceful resolution of the disputed territories between Armenia and

Azerbaijan on the principles to be laid down in the peace treaty to be

concluded between the RSFSR and the Republic of Armenia as soon as possible” [98]

(see Maps 8 and 9). Thus the Soviet

negotiators assured their Armenian counterparts that the occupation of the

disputed territories by the Red army did not necessary mean their annexation

by Soviet Azerbaijan but was of a temporary character and would not last only

until the future peace treaty is concluded by all the involved parties to

resolve all the border disputes. Armenia was also given ex-territorial rights

for the Shakhtakhty-Julfa section of Erevan-Julfa railway[99]. According to Hovannisian,

the preliminary treaty between Soviet Russia and Armenia was a result of

Soviet bogging down in the war against Poland and the anti-Soviet government

of Baron Wrangel as well as the dangerous anti-soviet uprising in Kuban[100].

In any case, that treaty gave Armenia 22 days of peace interrupted

only by sporadic attacks on Sadarak-Karabaglar section of Erevan-Julfa

railway performed by Muslim irregulars from Persian territory (see Map 9). After August 10, some fighting also

continued in Zanghezur where the Armenian forces under Lieutenant Colonel

Garegin Njdeh refused to evacuate and the mountainous area of southern

Zanghezur between Gerusy (Goris) and Meghri which they kept under stable

control even after the August counter-offensive of Soviet General Nesterovsky[101].

The guerillas of Njdeh kept their formal loyalty to the Republic of Armenia

and were getting some support from Erevan but that support was of rather

private than official nature. Map 9. Click on the map for better resolution The First Phase of the Turkish-Armenian War and the

Soviet-Turkish Invasion of Zanghezur 09/1920 – 10/1920 It would be beyond the framework of this essay to

provide a detailed analysis of the Turkish-Armenian War that broke out in

early September, 1920, when the Turkish army under Karabekir enforced by

local Muslim militiamen, launched a full-scale offensive along the whole

perimeter of Turkish-Armenian border. We would only take the liberty to

mention that the leadership of the First Republic definitely under-estimated

both military and ideological strength of Turkish nationalists

overestimating, at the same time, their own resources and forces as well as

the possible support on behalf of their Western Allies. On September 24 the

war was officially declared. Within the following week, the defense

lines of Armenian forces collapsed and the Turks took over the towns of

Sarykamysh, Kaghyzman, Ighdyr and Merdenik (see Map 9). The advancing Turkish

armies were devastating the area and wiping out the civil Armenian population

that did not have time or willingness to flee. Simultaneously, some of

Armenian regiments reportedly started performing ethnic cleansing in Kars and

Erevan counties that still remained under Armenian control. While Armenia was busy trying

to withstandthe new Turkish aggression, the Soviets made one more attempt to

“pasify” Zanghezur. On September 3 the

components of the 11th red Army under General Nesterovsky launched

an offensive against Njdeh pressing his fighters southwards beyond Kapan and

Katar. Three weeks later the combined Soviet-Turkish and Soviet-Azerbaijani

forces started incursion from Nakhichevan and Jabrail in the direction of

Meghri. Despite such dramatic development the militias of Zanghezur succeeded

in defeating the enemy groupings one after another and by the end of the

second week of October they re-conquered Kapan and Katar from Nesterovsky and

chased the Soviet-Turkish corps under the cpmmand of Veysel Bey back to

Nakhichevan[102]

(see Map 9). Meanwhile, during the two-week lull that

followed after the loss of Penyak, Sarykamysh, Peniak and Merdenek, Georgia

attempted to take over the remaining part of the disputed Ardahan (see Map 9). On

October 1 1920, Georgian troops occupied the small area near Chyldyr

lake and entered the village of Okam (Gyole) on

the ”Armenian side” of Kura. The above

demarche caused indignation and protests on behalf of the Armenian Foreign

Affairs ministry especially keeping in mind that the capture of disputed area

was taken place during the negotiations Tiflis regarding the possible Armeno-Georgian

alliance aimed against Soviet and Turkish expansion. The talks ended up with

no result partially due to the efforts of Turkish diplomats in Tiflis who in

fact encouraged the government of Georgia to take over the disputed territories

to the south of Ardahan. A few days after the Georgian incursion

south of Kura, the Armenian command ordered the West Armenian regiment of

Sebough to move into Okam. In order to avoid military confrontation, the

Georgian troops evacuated Okam on October 6 and retreated back to Ardahan.

The Chyldyr sector with the town of Zurzuna remained under Georgian control,

and on October 13 it was ceremonially declared Georgian[103]. The

very same day the lull at the Turkish front was broken,

and the Republic of Armenia was in no position to re-take Chyldyr from

Georgia. Ironically, just four months later that was taken over by the Turks

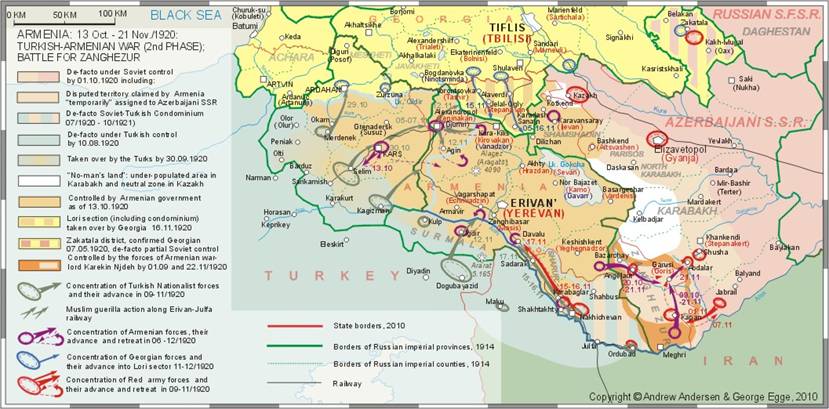

as a result of the Soviet-Turkish conquest of Georgia. Map 9. Click on the map for better resolution The Second Phase of the Turkish-Armenian War and the Fall of the

First Republic 10/1920 – 11/1920 In early October 1920, Armenian

Republic addressed the governments of Great Britain, France, Italy and other

Allied powers asking them to force the Turks to stop their offensive, but all

the desperate pleas for help seemed to fall upon deaf ears. Great Britain had

to concentrate most of her forces available in the Middle East to crush the

tribal uprisings in Mesopotamia (now Iraq). France and Italy had similar

problems in Syria, Cilicia and Adalia. The only country who provided some

support through active operations at the Turkish western front was Greece.

But Greek military support was not sufficient to ease Turkish pressure on

Armenia. As a result of the new Turkish

offensive the strategic town of Agin south of Alexandropol fell to the Turks

on November 12, and the Armenian troops were in retreat to the east along

Alexandropol – Karaklis railroad. The same day Armenian troops and population

started evacuation from Surmala crossing Aras river near Echmiadzin[107]

(see Map 10). At this point the Turkis were getting ready

for the final spurt on Erevan. Ironically enough, it was the beginning of

November when US President Wilson was done with the final sketches of the

Sevres-based Turkish-Armenian borders[108]

(see Figure 3.4). In the middle of November the

new Turkish offensive started in the direction of Erevan from Nakhichevan. In

breach of the Soviet-Armenian Treaty of August 10, the Nakhichevan

expeditionary corps contained the components of the Soviet 11th

Army. Between November15 and 16 demoralized Armenian troops left Shakhtakhty

and all of Sharur with little or no fight and stopped Soviet-Turkish offensive

only at Davalu on November 17 1920[109]

(see Map 10). The only war theater where

Armenians had significant success was Zanghezur. In that mountainous county

Armenian forces of Colonel Njdeh successfully repelled another

Soviet-Azerbaijani invasion from Jabrail in early November and on November 09

started counter-advance towards Goris (Gerusy). By November 22 the Armenians

of Zanghezur assisted by an expeditionary corps from Daralaghez completely

defeated the Soviet forces of General Pyotr Kuryshko (who replased

Nesterovsky in late October, 1920) and re-took the towns of Goris, Tatev,

Darabas and Angelaut expelling the reds out of the county as far as Abdalar

near the old administrative border of Karabakh[110]

(see Map 10). Map 10. Click on the map for better resolution

As a precondition

for any talks, the Armenian delegation headed by Alexander Khatisov was

forced to renounce the Treaty of Sevres[112].

After having complied with that demand under pressure the Armenians presented

their border proposal. Giving up most of the former Turkish Armenia including

the cities of Bitlis, Erzurum and the coastal city of Trebizond granted at

Sevres the the delegation of the Armenian Republic asked for the small parts

of the vilayats of Van and Bitlis with the cities of Van, Bayazet, Mush and

Khnys as well as for the narrow corridor in Lazistan with the town of Rize.

As for the former Russian Armenia, the Armenians hoped to keep the whole of

the province of Erevan and the territory of Kars[113]

The Armenian proposal was flatly rejected by the

Turkish delegation presided by General Nizam Karabekir Pasha as absolutely

non-realistic and even insulting. Instead, the Armenian delegation was to

accept unconditionally the Turkish provisions that were quite severe. Armenia

was to disarm most of her military forces and cede more than a half of her

pre-war territory. All of the Kars territory with the districts of

Sarykamysh, Kars, Kaghyzman, Olti and the Armenian sector of Ardahan district

was to be ceded to Turkey, as well as the county of Surmala in the province

of Erevan with the city of Ighdyr and Mount Ararat. The county of Nakhichevan

combined with the Sharur sector of the county of Sharur-Daralaghez were to be

placed under Turkish protectorate (see Figure 3.5). Self-explanatory, Armenia was not receiving any parts of

the Turkish Armenia that was now referred to as “Eastern Anatolia” by the

Turks. The Armenian Republic was also supposed to limit her relations with

the Allied Powers[114]. According to

Karabekir, the Turkish-drafted border between Turkey and Armenia was based on

“ethnical principle” that could not justify incorporation into Armenia of any

territories where Armenians had not formed majority before the outbreak of

the First World War[115]. The Final Soviet

takeover, 11/1920 – 02/1921 As early as on November 19

1920, the Soviet plenipotentiary in Erevan Boris Legran and his staff started

the arrangement of the bloodless Sovietization of Armenia following the

instructions from the Kremlin. The Dashnakist leadership of Armenia were to

be persuaded that that would be the only way to save Armenian people as well

as some form of the Armenian statehood[116]. At the same time, the Kavburo in Baku dominated by Orjonikidze

and Stalin was more impatient about the rapid conquest of exhausted Armenia

than Lenin and Chicherin in Moscow. Contrary to the instructions coming from

their communist party bosses from the Central Committee in the Kremlin, the

Caucasian Bolsheviks formed the Armenian Revkom

(Military Revolutionary Committee) in Baku on November 22, 1920, that was

designed to become the new communist government of Armenia. Three days later

the Revkom departed for Kazakh were the units of the Soviet 11th Army under

General Kuryshko (just recently defeated in Zanghezur) were preparing for the

invasion of Armenia. Same day the “Special Armenian Rifle Regiment”

previously stationed in Kedabek was re-deployed to Kazakh as well. The

invasion started o the night of November 28-29 by crossing the demarcation

line between Armenia and Soviet Azerbaijan south-east of Kazakh in the

direction of Karavansaray and Sevkar (Karadash). The two towns fell into the

hands of the Reds after some resistance on behalf of Armenian border guards

and militias was crushed by the end of November 29. The attempts of Armenian

General Seboukh (Arshak Nersisian) to organize counter-offensive from Dilijan

failed due to the unwillingness of the Armenian soldiers to fight one more

war against superior enemy, and on November 30 the Red Army was already in

Dilijan from where the Sovietization of Armenia and the overthrow of the

Dashnakist government was proclaimed[117].

Later, the soviet historians portrayed that military operation as a

“communist uprising of November 28 in the district of Kazakh”[118]

(see Map 11). The Soviet invasion from Kazakh

not only shocked the Armenian government but greatly confused Boris Legran

who had not been informed on those plans of the Kavburo. Nevertheless the

reaction of the Soviet envoy was quick and effective. By December 2, Legran

successfully pressured the Parliament and the Cabinet of Simon Vratsian to

step down and officially transfer the whole power to General Dro pending the

arrival of Revkom to Erevan. Two

days later, on December 4, Dro left Erevan for the lake Sevan area where he

welcomed the Revkom and, in turn,

gave up his power to the new Bolshevik administration. Two more days later,

the first units of the red Army entered the Armenian capital[119].

Thus the first Armenian republic shared the fate of the first republic of

Azerbaijan, and independent statehood of both nations was interrupted for

more than 70 years until August 1991. |

|

|

![]()

![]()