|

|

|

ARMENO- AZERBAIJANI TERRITORIAL DISPUTE AND THE FORMATION OF THE USSR(1920-1936): HOW THE TIME BOMB WAS PLANTED Andrew ANDERSEN, George EGGE

|

|

|

|

The Final Soviet

takeover (12/1920); Karabakh-Zanghezur and Nakhichevan taken over by Armenia? The Sovietization of Armenia was

accompanied by some events that at first sight, looked like the resolution of

the territorial dispute over Karabakh, Zanghezur and Nakhichevan. As has

already been mentioned above, the Soviet takeover of some territories claimed

by both Azerbaijan and Armenia did not necessarily imply their official

status. The documents and governmental correspondence of the described period

proves that Soviet envoys in the South Caucasus used to promise the disputed

territories to Azerbaijan while talking to the new Soviet leadership in Baku

or the Kemalist representatives, and to Armenia as a price for her

Sovietization when talking to Armenian communists. Sometimes they went so far

as to make absolutely unrealistic proposal according to which “no single

Armenian village will be given to Azerbaijan while no single Muslim village

will be given to Armenia”[1].

But while promising territorial concessions to all potential allies the

Kremlin tried to keep Karabakh, Nakhichevan and parts of Zanghezur as long as

possible under Soviet Russian military administration[2]. The Power Transfer Document

compiled on December 2 1920, and published in 1928 In Moscow and Paris

contained Paragraph 3 that defined the territory of the Sovietized Armenia as

recognized by the Russian Soviet Government. It included the whole of the

province of Erevan with the counties of Surmala, Sharur-Daralaghez and

Nakhichevan, Southern sector of the county of Borchalo in the province of

Tiflis, the whole of the county of Zanghezur in the province of Elizavetpol and

parts of the county of Kazakh and the territory of Kars that were not clearly

defined[3]

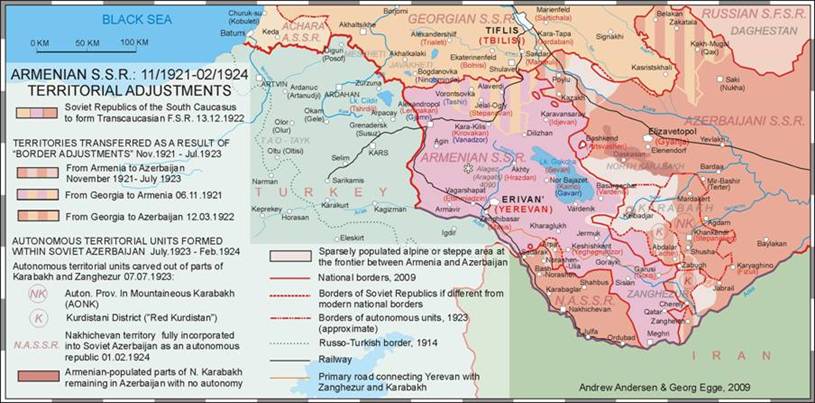

(see Map 11).

Ironically enough, neither the last Dashnakist government, nor the first

Soviet administration in Erevan could boast effective control even over the

half of the above territory. However, the above document is important in

terms of serious territorial concessions that the Kremlin was prepared to

offer Armenia at the very first stage of her Sovietization. Just the day before, on

December 01, 1920, a few hours prior to the power transfer in Erevan and two

days after the declaration of the Sovietization of Armenia by the

Kazakh-Dilijan Revkom, the Soviet

government of Azerbaijan (also referred to as Azrevkom) sent its greeting to its Armenian accomplices and

declared that from the moment of the fall of “the Dashnakist regime”, the

Soviet Azerbaijan was giving up the disputed territories of Karabakh,

Zanghezur and Nakhichevan in favor of the Soviet Armenia[4].

That act of the Soviet leadership of Azerbaijan was later revoked as will be

described below, but it was widely used by the Soviet propaganda to create a

myth that only the Bolsheviks with their “communist internationalism” have

proven to be the only power in the world capable to resolve long and violent

territorial disputes like the one between Armenia and Azerbaijan[5]. Map 11. Click on the map for better resolution The

Treaty of Kars, 13.10.1921 The partition of the South Caucasus as a result

of a series of wars in 1920-1921 was finalized by the Treaty of Moscow signed

on March 16, 1921 by the representatives of Soviet Russia and Kemalist

Turkey. The provisions of the Treaty confirmed the new borders of Armenia

that had just left the Soviet orbit as a result of an anticommunist uprising

(see above) and Georgia whose independence was recently recognized de jure by

the Allied powers and whose army and militias were still desperately fighting

in an attempt to repel the Soviet invasion. During the intensive talks

preceding the signing ceremony, the territories of the two nations were

partitioned and borders re-drawn in the absence of the representatives of

that nations. The Soviet leadership did not even invite to Moscow any

representatives of the puppet Soviet Revkoms

of Armenia and Georgia. Almost seven months later, on October 13,

1921, the treaty containing basically the same provisions as the Treaty of

Moscow was signed in Kars. This time it was signed not only by the

representatives of Turkey and Russia but also by the ones representing the

Soviet governments of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. According to the

Treaty of Kars, the treaties of Sevres and Alexandropol (see above) were denounced and both the

Turkish and Armenian sides agreed to forgive each other all the “military

crimes and mistakes” committed by their representatives during all the wars,

conflicts and ethnic cleansings of 1915-1920. However, despite the formal renouncement of

the technically illegal Treaty of Alexandropol, the Treaty of Kars

reconfirmed the Turkish-Armenian boundary outlined in it by leaving Turkey

with most of the territories conquered during the Turkish-Armenian war as

well as the Soviet-Turkish war against Georgia[6].

Turkey re-gained almost all the territories lost to the Russian Empire during

Russo-Turkish war of 1978, except the northern half of Achara (i.e. northern

half of the territory of Batum) and the tiny Shuragel (Aghbaba) sector in the

north-eastern corner of the territory of Kars. Within the above territories

ceded to Turkey were the towns of Artvin, Ardahan, Oqam, Olor, Olty, Poskhov,

Sarykamysh, Kaghyznman and Kars. Turkey was also granted the county of

Surmala of the former Erevan province to the south of the river of Aras with

the town of Ighdyr and the mountain of Ararat (the national symbol of

Armenia). The county of Surmala had never been a part of Turkey before,

except a short period between 1724 and 1735, and as per the Treaty of Kars,

Turkey became the only country among those defeated

during World War I that ended up with a territorial gain (see Map 12).

Turkey also dropped all the claims to the counties of Sharur-Daralaghes and

Nakhichevan of the former province of Erevan under the condition that the

county of Nakhichevan, western part of the county of Sharur-Daralaghez (more

or less correspondent with Bash-Norashen sector) and a small strip in the

county of Erevan with the village of Sadarak, was to become a special

autonomous territory under the protection of Soviet Azerbaijan. The creation

of a special autonomy in Sharur-Nakhichevan subordinate to Baku was in

conflict with the declaration of Azrevkom

of December 1, 1920. But that declaration had been revoked prior to the

Treaty of Kars, as will be explained below. The borders of the new autonomy

carved out of the province of Erevan, were drawn in such a way that it had a

land bridge to Turkey (after Turkey got the county of Surmala). Soviet

Armenia and the first delimitation of the Soviet South Caucasus, July-October,

1921 In summer and early fall of 1921 the Soviet

Armenia was in effective control of the following territories (See Map 12):

A few comments need to be made regarding

Armenian sovereignty over Zanghezur and Kazakh: (1)

As of today, by “Zanghezur” one usually means modern

province of Syunik in Armenia. However, as of 1917-1921, the county of

Zanghezur embraced much bigger territory including the strategically

important villages of Abdalar (Lachin) and Zabugh. (2)

The Armenian possessions in the county of Kazakh

remained untouched by the territorial adjustments for a short while as a

“cradle of Armenian revolution” where in accordance with the Soviet

ideologized history the communist uprising had been staged in late November,

1920. In fact, even pre-Soviet Armenia never claimed the whole territory of

that county restricting her aspirations to its predominantly

Armenian-populated mountainous part and having little interest to the lower

Kazakh with its Azeri-Tatar majority (excluding a few Tat, Armenian and

German villages). Most of the Soviet

maps depicting Armenia of mid-1921, show her in possession of the county of

Kazakh excluding the strip of land between the rivers Kura and the border of

Georgia just south of Iori river[7].

Some of the maps of that period, however, show Armenian SSR stretching across

Kura and thus embracing the whole county. As of today, it is hard to say

whether this discrepancy was a result of poor quality of early Soviet maps or

the lack of documentation regarding the borders between the new Soviet

republics. We assume that it is quite unlikely that there was any Armenian

administration in 1921 that would claim control of the deserted strip of land

north of Kura and that is reflected in Map 12 where Kura is shown as the

northern border of the Soviet Armenia in Kazakh-Shamshadin. As follows from the above, the Soviet Armenia

did not have any formal control of Karabakh during the period specified,

contrary to the declaration of Azrevkom

of December 1, 1920 in accordance with which Mountainous Karabakh was to

become an integral part of Armenia together with Zanghezur and Nakhichevan. Map 12. Click on the map for better resolution As was already mentioned, the Treaty of

Kars put Nakhichevan together with some other territories next to it under

the protection of the Soviet Azerbaijan, while the desperate struggle of the

population of Zanghezur prevented secession of this territory from

Armenia. As for the Mountainous

Karabakh, its transfer to the Soviet Armenia was revoked by the decision of Politburo of the Communist Party of

Azerbaijan (the body de-facto running the Azerbaijani Soviet Republic) of

June 27, 1921[8], and

the future of Karabakh was to be decided at the plenary session of the Kavbureau of the Central Committee of

Russian Communist Part (Bolsheviks)[9]

that started on July 4, 1921. After hours of heated debates, the Kavbureau decided to overrun the 1920

declaration of Azrevkom by leaving

Mountainous Karabakh within Azerbaijan and promising it cultural and

territorial autonomy [10].

Sixteen days later, the Central Committee of the Communist party of Armenia

protested the Kavbureau decision

but the protests from Erevan and Armenian-populated parts of Karabakh were ignored by the Kremlin, and even the promised autonomy

was not established in Karabakh until 1923[11].

On July 5, 1921, the Kavbureau also

failed to define the borders of Mountainous Karabakh in general and

the future autonomy in particular leaving it for the future decisions and

agreements[12]. The frameworks of this paper do not allow

us to make a detailed analysis of the possible reasons for the Kremlin

support of the territorial ambitions of the Soviet Azerbaijan at the expense

of the Soviet Armenia. We would take the liberty to suggest that oil-rich

Azerbaijan could be more important to the Soviet leadership in Moscow as a

possible spearhead of their expansionist policies in the Middle East and

other Muslim-dominated areas, while the National Uprising in Armenia and

especially in Zanghezur, put Armenian loyalty to the new Soviet system in

question. Until the end of 1921, the Soviet Armenia

also did not include any parts of the county of Borchalo that had been

disputed with Georgia since late 1918. The Kremlinite logic behind keeping

the whole of Borchalo within the Soviet Georgia was the same as behind

keeping the whole of Kazakh within Armenia: the pro-Soviet uprising in

Georgia in February, 1921, started in

a few ethnically Armenian villages of the sector of Lori (Borchalo county)[13],

and ceding that territory to Armenia immediately after the end of

Soviet-Georgian war, could question the legitimacy of the Sovietization of

Georgia[14]. To

the Transcaucasian SFSR and the USSR: territorial changes of Nov/1921-

July/1923 In order to soften the loss of formal

independence of the new-conquered Soviet republics of the South Caucasus an

order was given from Moscow to their leaders to form a pseudo-federation of

three units that later were to be incorporated into the Soviet Union - a prototype of the “Global Soviet Republic”

planned by the architects of “the world revolution”[16].

It is important to keep in mind that as soon as the short-lived states of the

South Caucasus were Sovietized, they were run by the local communist parties

that, in fact, were not independent communist parties but constituent parts

of ARCP(B), local branches of “highly-centralized political organization

directed by a small group of men in Moscow”[17]

and bound by strict party discipline. Following the orders from Moscow and Zakkraykom of RCP(B) that replaced the

Kavbureau RCP(B) in February, 1922,

the representatives of the three Soviet republics of the South Caucasus

(Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia) signed on March 12, 1922, in Tbilisi the

federal treaty establishing the Transcaucasian

Federal Soviet Socialist Republic (also known as ZSFSR). Less than a year

later, on December 30, 1922, ZSFSR got completely absorbed by the

Bolshevik-recreated empire, through signing the Union Treaty that signaled

the establishment of the USSR formally and formally subordinated the three

Soviet republics (Belarus, Ukraine and the Transcaucasian Federation/ZSFSR)

to the Kremlin. The creation of ZSFSR was preceded by a few

rather major territorial changes that were supposed to put an end to all

possible territorial disputes between the three member-states of the Soviet

federation of the South Caucasus. Most of those changes contributed to the

territorial growth of Soviet Azerbaijan, except the treaty of November 6,

1921, that gave Armenia the sector of Lori of the county of Borchalo that had

been disputed between the two nations since 1918 and finally incorporated

into Georgia during Turkish-Armenian war of 1920 (see above) and southern part of Borchalo sector of the county

bearing the same name (see Map 13). The above adjustment of

Georgian-Armenian border was formally made in accordance with the declared

“ethnical principle” keeping in mind that the above territory had mixed

Armenian, Russian and Greek population with Armenian majority. Other territorial changes that occurred

immediately before and immediately after the creation of ZSFSR were made, as

already mentioned above, in favor of Soviet Azerbaijan. On March 12, 1922,

hours before the establishment of ZSFSR, despite some protests of Georgian

leadership, Azerbaijan was granted the long-disputed poly-ethnic Zakatala

district, and between November, 1921, and July, 1922, Soviet Armenia ceded to

Azerbaijan the following territories (see Map 13):

Map 13. Click on the map for better resolution Mountainous

Karabakh: autonomy created, but what exactly was Mountainous Karabakh? From the point of view of the Tatar

(Azerbaijani) officials both before and after the Sovietization of

Azerbaijan, by Karabakh one should mean the

four sanjaks, or the three counties of the former Russian province of

Elisavetpol, namely: Javanshir, Karyagino (Fizuli), and Zanghezur that

embrace the territory restricted by the rivers of Aras and Kura (in the east

and south), mountain ranges of Mrovdagh (in the north) and Zanghezur (in the southwest). The natural

western border of Karabakh is the line going from the mountain of Klyshdagh

to the mountain of Sarytshly and further to the mountain of Ginaldagh. Since

the 16th century, the described territory was nominally controlled

by the Khanate of Gyanja of the Persian Empire and since the middle of the 18th

century, it was organized into the separate Karabakh Khanate and remained in

that status until incorporation into the Russian Empire in 1823. Accordingly,

the western mountainous part of that territory could be defined as

Mountainous Karabakh. In the early 20-s the mountainous part of the four sanjaks (including the whole

of the Highland county of Zanghezur) was also often called “the Armenian

Karabakh” due to the fact that its inhabited area[18]

was predominantly Armenian-populated although it was also a home of a few Turcic and Kurd-speaking nomadic and

semi-nomadic groups. One should add to the above that even during the era of

the khanates of Gyanja and Karabakh, the mountainous areas of that region

were ruled by local Armenian Meliks

(Princes) thus existing in the form of several semi-independent feudal

mini-states among them Khachen, Jraberd, Varanda, Dizaq and Tsar[19].

From the Armenian perspective,

the above-mentioned territory was not the whole of Mountainous Karabakh

because Armenian political and intellectual elites of the period described,

considered the former Khanate of Gyanja (Gandzak) a part of historical

Kabarakh thus denoting most of Gyanja county of the province of Elisavetpol

between Mrovdagh range and Kura river

as “Northern Karabakh”[20].

Accordingly, the mountainous part of Gyanja county between Shakhdagh range

and the chain of villages including but not limited to Karatschinar, Agjakend

(Shaumianovsk), Borisy, Erketch and Chaykend on both banks of the river of

Geran, was considered a part of Mountainos Karabakh and often referred to as

“North Artsakh”. The described territory was even more homogenously Armenian

than Mountainous Karabakh south of Mrovdagh, local Armenians spoke the same

dialect that was used in the mountainous parts of the three sanjaks, and historically the above area was the core

part of the Armenian melikdom of

Gyulistan[21]. Additionally, another mostly

Armenian-populated part of the county of Elizavetpol (Gyanja/Gandzak)

described above as “the unknown Armenia” was lying to the west of North

Karabakh and included the Armenian villages of Ajikend, Mirzik, Bayan,

Dashkesan, Kushtshi, Zaghlik, Barsum and Tshardakhly. That area is often

referred to as the continuation of Northern Karabakh or as North-Western

Karabakh or Parisos. is also close to Mountainous Karabakh both historically

and linguistically but in contrast to Karabakh Armenians, the Armenians of

Parisos did not attempt to incorporate their lands into the Armenian Republic

and thus that territory was from the very beginning excluded from the

“autonomous Karabakh”[22]. It might be also worth mentioning that the

chain of Armenian towns and villages of Northern Karabakh looks on the map like

a long enclave with a reasonable chunk of Azerbaijani territory between them

and Armenia. That impression could be calibrated though, if one bears in mind

that most of the area south of that chain of Armenian settlements and almost

until the coast of lake Sevan, was practically uninhabited Highland area that

remains sparsely-populated even at present. Following the decision of Kavbureau of July 1921, it was

expected both in Karabakh and in Armenian SSR that the autonomy would be

granted to all Mountainous Karabakh including Armenian-populated areas of

Northern Karabakh. However the reality happened to be quite different from

Armenian aspirations. AONK

and “Red Kurdistan”: 07.07.1923 The history of the autonomous “Kurdistani

County” (also known as “Red Kurdistan”) is short and unclear most of the

documents referring to its existence are either destroyed or “classified”

both in Azerbaijan and Russia. Unclear are also the reasons of its creation.

In any case, the frameworks of this article do not allow us to go into the

details of the history of the “Red Kurdistan’, but it is quite evident that

one of its function was to create a Muslim buffer between autonomous

“Armenian Karabakh” and the rest of Armenia. The county included not only

westernmost parts of the former counties of Javanshir, Shusha and Karyaghino

(now Fizuli) but also most of the lands transferred from Armenian Zanghezur

to Azerbaijan in 1921-22, and the recently Armenian town of Lachin became an

official capital of the Kurdish autonomy although most its governmental

offices were located in Shusha.[26] If one looks at some of the

maps of the South Caucasus published in the USSR between 1923 and 1925, one

may notice that despite the fact that on some of them the town of Lachin

(Abdalar) did not belong either to Armenia, or to AONK, the Karabakh autonomy

was still not an enclave and had connection with Armenian Zanghezur at least

at the village of Zabugh, through which ran a road that connected the two

mountainous regions. If one tries to compare various maps of the area

published during the 20-ies, one gets an impression that the borders of AONK were

regularly redrawn. On the other hand, the jurisdiction of the major towns of

the autonomy and around it remains the same. As of today, it is extremely

hard to say whether this discrepancy is a result of bad cartography, or the

administrative borders were not clearly defined. The problem is aggravated by

the fact that both the military topographic maps of the area published during

the described period, and the documentation related to the re-carving of the

counties and other administrative units is still classified and not

accessible to the researchers. In any case, basing on the maps that still

exist and be found in the libraries as well as on the research made by Robert

Hewsen, Tim Potier and Artur Tsutsiev[27],

AONK had connection with Armenia in Zabugh at least until 1926. Territorial

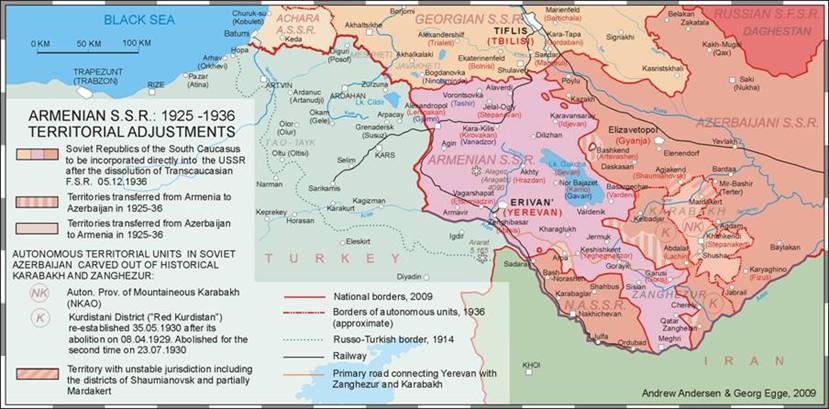

adjustments of 1925-1936 and the dissolution of ZSFSR The years of 1925-36 saw some more changes

on the administrative map of the South Caucasus especially in Mountainous

Karabakh and around it. During eleven-year period that ended up with the

dissolution of ZSFSR on December 5, 1936, the soviet republics of the South

Caucasus went through several re-organizations of their administrative

divisions. In Karabakh that process resulted in the abolition of Kurdish

autonomy on April 98, 1929 and its restoration on May 25, 1930.

Re-establishment of “Red Kurdistan” was accompanied by significant

territorial increase: in the south, the autonomous county gained Zanghelan

area and reached the river of Aras thus gaining direct access to Iran. Near

its capital (Lachin area) the Kurdistani county was supplemented with Zabugh

thus cutting AONK off from Armenia, as well as with the villages of Minkend,

Bozlu and Bayandur apportioned from Armenian Zanghezur and a small area

around lake Alagel. Despite the territorial growth of “Red Kurdistan” it lost

considerable amount of Kurd population through migration, famine, political

repressions and assimilation. The autonomy and especially the town of Lachin

were heavily settled by Azeri Turks (Tatars) who were brought there from

various parts of Azerbaijan. Finally, on August 8, 1930 the Kurdistani

autonomy was abolished for the second time. Now AONK became an isolated

enclave surrounded by Azerbaijani territory. In most of the Northern

Karabakh and North-Western Karabakh/Parisos ethnically Armenian villages and

towns were incorporated into new districts of the Azerbaijani SSR. Those

districts were much smaller than old imperial counties, but they were

organized in such a way that the majority of their population was Turkic with

small and rather marginalized Armenian presence. The only part of Northern

Karabakh that managed to be organized into almost purely Armenian district,

was historical melikate of

Gyulistan now known as Shaumianowsky district (the Soviets renamed the town

of Agjakend to Shaumianovsk) In 1925-36 Armenia was forced to cede other

territories to Azerbaijan including a few villages in Zanghezur (finally

leaving Armenia with only half of the pre-1921 Zanghezur county), and a few

villages in Shamshadin around the town of Artsvashen (Bashkend) turning it

into an Armenian enclave inside Azerbaijan. At the same time, the village of

Arpa, previously given to Nakhichevan ASSR[28]

(see above) was returned to Armenia thus restoring

connection between Erevan and the towns of Zanghezur (See Map 14). One can say that by the end of the 30-ies the

borders between Armenia and Azerbaijan were finally stabilized and started

looking approximately the way they looked prior to the escalation of the

Karabakh conflict in the mid-80ies. The finalized borders, however, satisfied

neither Armenians, nor Azeri Tatars[29].

(at that tine the word “Tatar” or “Azeri Tatar” was replaced with the term

“Azerbaijani” or “Azeri”). Map 13. Click on the map for better resolution |

|

|

![]()

![]()