|

|

|

AZERBAIJAN AT THE VERSAILLES CONFERENCE Firuz KAZEMZADEH Excerpt

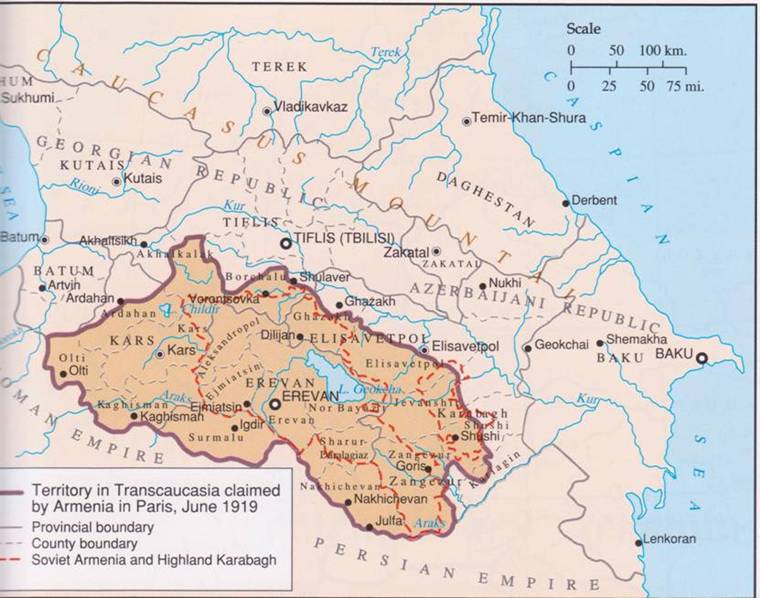

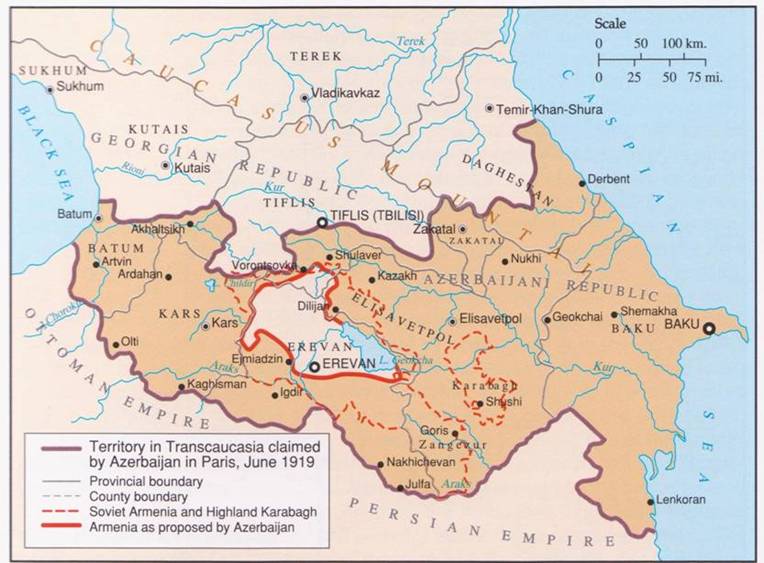

from Chapter XVII from the book “STRUGGLE FOR TRANSCAUCASIA” / Oxford, 1951 Maps: Richard G. Hovannisian and Robert H. Hewsen

|

|

|

|

The Claims of

Azerbaijan Upon its arrival in Paris the

Azerbaijani delegation addressd a note to President Wilson, making the

following requests: 1. That

the independence of Azerbaijan be recognized, 2. That

Wilsonian principles be applied to Azerbaijan, 3. That

the Azerbaijani delegation be admitted to the Peace Conference, 4. That

Azerbaijan be admitted to the League of Nations, 5. That

the United States War Department extend military help to Azerbaijan, and 6. That

diplomatic relations be established between the USA and Azerbaijan[1]. President Wilson granted the

Azerbaijani delegation an audience, at which he displayed a cold and rather

unsympathetic attitude. As the Azerbaijani delegation reported to its Government,

Wilson had stilted that the Conference did not want to partition the world

into small pieces. Wilson advised the Azerbaijanis that it would be better for

them to develop a spirit of confederation, and that such a confederation of

all peoples of Transcaucasia could receive the protection of some Power on

the basis of a mandate granted by the League of Nations. The Azerbaijani

question, Wilson concluded, could not be solved prior to the general settlement

of the Russian question[2]. The Claims of Persia The work of the Azerbaijani

delegation was considerably hampered by the efforts of the hostile remnants of

the Russian Tsarist diplomatic apparatus, who left no stone unturned to

discredit the Transcaucasian delegations and the very idea of an independent

Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia. Moreover, Persia presented to the Conference

her claims to a part of the Russian territory. Ali Qoli Khan Moshaver'ol’Mamalek,

the Persian representative, handed the Conference a memorandum, which

included the following claims: “In the

North, the cities and provinces wrested from Persia after the Russian wars.

We will cite Bacou, Derbent, Chakki, Chemakha, Guendja (Elizabethpol),

Karabagh, Nakhdjevan, Erivan. These provinces must be returned to Persia, for

they had already formed part of Persia. The large majority of their

inhabitants are Musulmans, and the generality of them are Persians in origin

and race. In fact, from every point of view, historic, geographic economic, commercial,

religious, cultural, they are attached to Persia. Furthermore, a large

portion of the inhabitants of these provinces have lately appealed to the

Government of Teheran, to protect them, and they have expressed the wish to

be restored to Persia”.[3] The claims of the Persian delegation

were fantastic. They showed a complete lack of understanding of the historical

forces which were shaping the destinies of the world. Poverty-stricken

Persia, whose own existence was threatened every day, the corruption of whose

Government and the weakness of whose army made her an easy prey to the

internal as well as the foreign plunderer, was certainly in no position to

enter the struggle for Transcaucasia. The efforts of the Persian delegation

did not end with the presentation of an official memorandum to the

Conference. They tried to mobilize public opinion in their favor by holding

meetings and distributing literature. But the conference dealt unkindly with

them. They were not even admitted In its work.[4] Fortunately for Azerbaijan, Persian

claims were not taken seriously. The cold reception accorded to the

Azerbaijan delegation by Wilson did not discourage them. Having failed to win

the heart of the American President, they presented the Conference with their

official claims: I The Peace

Conference approves the separation of the Caucasian Azerbaijan from the

former Russian Empire. Azerbaijan shall form an absolutely independent State

under the name of the Demo¬cratic Republic of Azerbaijan . . . II The

representatives of the Republic of Azerbaijan shall be admitted to the work

of the Peace Conference and its Committees. III The Republic of Azerbaijan shall be admitted among the members of the

"League of Nations", under the high protection of which this

Republic wishes to be placed like other States”[5]. Azerbaijan failed to gain

recognition in 1919. The issue was complicated by the presence of the

Volunteer Army in the Northern Caucasus, by the plans to place Transcaucasia

under Italian protection, by the uncertainty of the position of the Russian

Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, and finally by the constant quarrels of

the Azerbaijani and the Armenian delegations, in Paris, quarrels which

reflected the state of affairs in Transcaucasia. A sharp conflict developed at Paris

over the Nakhjavan district, thr Azerbaijani delegation trying to prove that

this area, claimed by Armenia, should really belong to Azerbaijan.[6]

The Armenians were not to be outdone. They came back with stacks of

documents, accusing the Azerbaijanis of exaggerating the number of Muslims in

the Nakhjavan district and in Karabagh, and of harboring sinister designs

against innocent Armenia.[7]

In January, 1920, the Allied Supreme

Council suddenly extended its de facto recognition to Azerbaijan. Bulletin d'information de I' Azerbaidjan

wrote: "The Supreme Council at one of its last sessions recognized

the de facto independence of the Caucasian Republics: Azerbaijan, Georgia,

and Armenia. The delegations of Azerbaijan and Georgia have been notified of

this decision by M. Jules Cambon at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on 15th

January, 1920."[8]

Behind the sudden recognition there was a weighty reason: the failure of

Denikin, Allied Concern over

the Threat of Bolshevism The defeat of the Volunteer Army

worried the Allies. A short article in the London Times revealed their

apprehension over the future: “As a

result of the Bolshevik occupation of Trans-Caspia, which may now be regarded

as practically complete, the situation in the Caucasus has become one of

considerable difficulty . , . Georgia and Azerbaijan are anti-Bolshevik, both

as regards their V Governments and the population, but their armed strength

is insufficient to resist invasion which now threatens them from the north,

where Denikin's right wing is being pressed back, and from the east across

the Caspian.”[9]

By recognizing the Transcaucasian

Republics the Allies hoped to itrengthen their position in regard to Soviet

Russia. In the House of Commons the Under

Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Mr. Greenwood, was asked on what date

recognition had been extended to Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia, and

whether "in accordance With such recognition, official representatives

have been exchanged, and the boundaries of the Transcaucasian Republics

defined," Mr. Greenwood replied: “Instructions

were sent to the British Chief Commissioner for the Georgian and

Azerbaijanian Governments that the Allied Powers represented on the Supreme

Council had decided to grant de facto recognition to Georgia and Azerbaijan,

but that this decision did not prejudge the question of the respective

boundaries . . . There has been no change in representation as a result of

recognition; as before, His Majesty's Government have a British Chief

Commissioner for the Caucasus with Headquarters at Tiflis, and the three

Republics have their accredited representatives in London ...”[10] On 15th January, 1920, the London Times wrote that with the defeat of

Denikin the Transcaucasian republics would have to lean on Persia[11],

while a French radio station broadcast on 21st January, 1920, that the

British were ready to send ten thousand men to Baku in order » to prevent the

Bolsheviks from occupying that important city. The broadcast stated that

Lloyd George had forced the French Government j |o increase their army of

occupation in Germany so as to relieve the British who would be sent to the

Caucasus, and said bluntly that for once Lloyd George and Churchill were

agreed in their desire to stop the Bolshevik penetration which threatened

Persia, India, Turkey, and Mesopotamia.[12] The sensational announcement of the

Lyons radio is not to be taken seriously, but even this fantastic broadcast

indicates the general feeling which prevailed in Europe in 1920. "Stop

the Bolsheviks!" was the battle-cry, to which, however, only a few

responded. Europe had suffered too much in the war, the wounds were too

fresh, she would not concern herself with peoples whose very names were

unknown to I her masses. Soviet historians have exploited newspaper headlines

which called for a crusade against Bolshevism, and the statements of such

determined anti-Communists as Winston Churchill, to show that the entire

world had united against their young Republic. Facts tell a rather different

story. The Allies recognized the Transcaucasian Republics partly because of

their fear of Bolshevism, but their activities directed against Bolshevism,

at least in Transcaucasia, did not go much beyond words, the strongest of

which were status quo, recognition, demarche, and a list of standard

diplomatic remonstrances. No British troops arrived in

Azerbaijan. At the end of the winter of 1920, it looked from Paris as though

the situation in the Caucasus was beginning to stabilize. The Georgian and

Azerbaijain delegations addressed a joint note to the Ambassador of the

United States in Paris, pointing out that their countries had been granted de facto recognition by the Conference

and requesting the establishment of diplomatic relations between them and

America. The American Government ignored this request. There was little more

that the Azerbaijani delegation could accomplish. They could only wait for

events to take their course. |

|

|

![]()

![]()