|

|

|

Turkish-Armenian

War and the fall of the First Republic By Andrew Andersen and Georg Egge

|

|

|

|

Escalation of Tension between Armenia and Nationalist Turkey and

the Failed Alliance with Georgia, 08/1920 – 09/1920 The aftermath of the Treaty of

Sevres was marked by the following paradox. On the one hand, Armenia was

supposed to take over the territory now legally assigned to her by the

victorious Allies and was willing to do so. But on the other hand, the

Turkish Kemalists who in fact, controlled the territory assigned to Armenia

together with most of Anatolia, did not recognize the Treaty that had been

signed (although never ratified) by the powerless government of Sultan Mehmed

VI based in Constantinople and were not planning to give up any territory

that they considered Misak-i-Milli

(Turkish heartland). Furthermore, from the Kemalist/Nationalist perspective, Misak-i-Milli included not only

Western Armenia but at least half of the territory controlled by the Armenian

Republic in August, 1920 (all the territory west of the Russo-Turkish border

of 1877). Facing the above paradox the Democratic Republic of Armenia could

enforce provisions of the Treaty of Sevres only through successful military

action, but was the tiny republic of the South Caucasus capable of completing

that task? By the end of summer of the year 1920, Armenia could boast less

than 30 000 soldiers against the 50 000 strong Turkish army of Nizam

Karabekir Pasha stationed at her pre-treaty borders[3]

despite the fierce fighting going on in Western Anatolia between the Kemalist

Turks and Greeks who were trying to secure their own gains as per the Treaty

of Sevres. In addition to the regular troops, Karabekir could rely on

numerous irregulars who were also prepared and willing to fight for the

Turkish case against Armenians. As for the Armenian army that was believed to

be the best trained and the most disciplined among other armies of the South

Caucasus, it would hardly be an exaggeration to say that it was exhausted -

morally, physically and financially as a result of the series of almost

non-stop warfare starting with 1915. In terms of international support, one

could add to the above that the events that followed the Treaty of Sevres in

the South Caucasus clearly demonstrated Armenia could hardly count on any

serous external help while the Kemalist (Nationalist) Turkey enjoyed both

diplomatic and military support on behalf of the Soviet Russia and its

puppet-state of Soviet Azerbaijan[4].

Armenian officer,

August / 1920 Several weeks before the treaty of Sevres

was signed, Armenian border troops entered the district of Olti, the

territory that formally did not belong to Turkey but in fact, was controlled

by the irregulars of local Muslim warlords ( predominantly Kurdish ones) as

well as by some regular Turkish troops under the command of Turkish and

Azerbaijani officers who were stationed there in breach of the Armistice of

Mudros[5].

The Armenian advance began on June 19, 1920, and by June 22 most of the district

including the towns of Olti and coal-reach Peniak were put under Armenian

jurisdiction[6]

(see Map 8). From Turkish Nationalist perspective, it was the incursion of

the Armenian troops into the district of Olti that served as an official pretext

for the new Turkish-Armenian war. One should add to the above that the war

could have been avoided if the governments of Armenia and Georgia would have

succeeded in the establishment of a military alliance aimed at preservation

of their independence and territorial integrity. The government of the First

republic undertook some demarches in that direction in mid-August, 1920[7]

largely under the influence of Lt.-Colonel Claude Stokes (new British chief

Commisioner in the South Caucasus) who was a strong believer that

Armeno-Georgian alliance could have not only secured the area from the new

Turkish expansion but could have also resulted in forcing the Soviets out of

Azerbaijan[8]. The

possibility of such an alliance was a great concern for the Turkish

Nationalists even in the midst of the Turkish-Armenian war that started 40

days upon the signing of the treaty of Sevres[9].

Nevertheless, the projected Armeno-Georgian alliance never occurred due to

the inability of the governments of both nations to overcome their differences

and due to the efforts of Turkish diplomacy in Tiflis. The First Phase of the Turkish-Armenian War and the

Soviet-Turkish Invasion of Zanghezur 09/1920 – 10/1920 It would be beyond the framework of this

essay to provide a detailed analysis of the Turkish-Armenian War

that broke out in early September, 1920, when the Turkish army under

Karabekir enforced by local Muslim militiamen, launched a full-scale

offensive along the whole perimeter of Turkish-Armenian border. We would only

take the liberty to mention that the leadership of the First Republic

definitely under-estimated both military and ideological strength of Turkish

nationalists overestimating, at the same time, their own resources and forces

as well as the possible support on behalf of their Western Allies. On

September 24 the war was officially declared. Within the following week,

the defense lines of Armenian forces collapsed and the Turks took over the

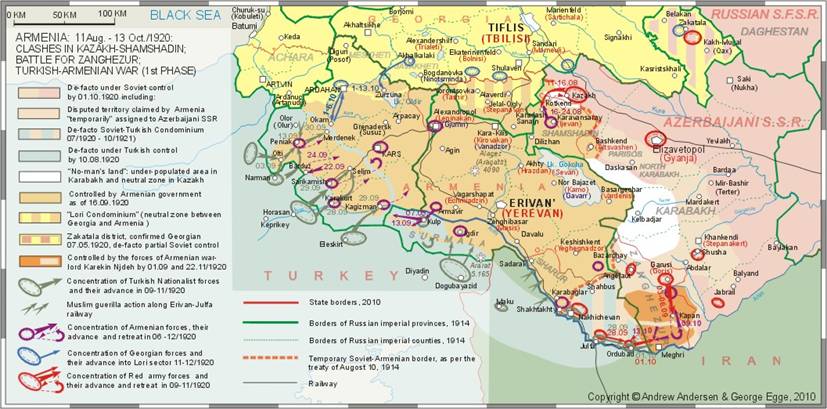

towns of Sarykamysh, Kaghyzman, Ighdyr and Merdenik (see Map 9). The

advancing Turkish armies were devastating the area and wiping out the civil

Armenian population that did not have time or willingness to flee.

Simultaneously, some of Armenian regiments reportedly started performing

ethnic cleansing in Kars and Erevan counties that still remained under

Armenian control. While Armenia was busy trying

to withstandthe new Turkish aggression, the Soviets made one more attempt to

“pasify” Zanghezur. On September 3 the

components of the 11th red Army under General Nesterovsky launched

an offensive against Njdeh pressing his fighters southwards beyond Kapan and

Katar. Three weeks later the combined Soviet-Turkish and Soviet-Azerbaijani

forces started incursion from Nakhichevan and Jabrail in the direction of

Meghri. Despite such dramatic development the militias of Zanghezur succeeded

in defeating the enemy groupings one after another and by the end of the

second week of October they re-conquered Kapan and Katar from Nesterovsky and

chased the Soviet-Turkish corps under the cpmmand of Veysel Bey back to

Nakhichevan[10]

(see Map 9). Meanwhile, during the two-week lull that

followed after the loss of Penyak, Sarykamysh, Peniak and Merdenek, Georgia

attempted to take over the remaining part of the disputed Ardahan (see Map 9). On

October 1 1920, Georgian troops occupied the small area near Chyldyr

lake and entered the village of Okam (Gyole) on

the ”Armenian side” of Kura. The above

demarche caused indignation and protests on behalf of the Armenian Foreign

Affairs ministry especially keeping in mind that the capture of disputed area

was taken place during the negotiations Tiflis regarding the possible Armeno-Georgian

alliance aimed against Soviet and Turkish expansion. The talks ended up with

no result partially due to the efforts of Turkish diplomats in Tiflis who in

fact encouraged the government of Georgia to take over the disputed

territories to the south of Ardahan. A few days after the Georgian incursion

south of Kura, the Armenian command ordered the West Armenian regiment of

Sebough to move into Okam. In order to avoid military confrontation, the

Georgian troops evacuated Okam on October 6 and retreated back to Ardahan.

The Chyldyr sector with the town of Zurzuna remained under Georgian control,

and on October 13 it was ceremonially declared Georgian[11]. The

very same day the lull at the Turkish front was broken,

and the Republic of Armenia was in no position to re-take Chyldyr from

Georgia. Ironically, just four months later that was taken over by the Turks

as a result of the Soviet-Turkish conquest of Georgia. Map 9. Click on the map for better resolution The Second Phase of the Turkish-Armenian War and the Fall of the

First Republic 10/1920 – 11/1920 In early October 1920, Armenian

Republic addressed the governments of Great Britain, France, Italy and other

Allied powers asking them to force the Turks to stop their offensive, but all

the desperate pleas for help seemed to fall upon deaf ears. Great Britain had

to concentrate most of her forces available in the Middle East to crush the

tribal uprisings in Mesopotamia (now Iraq). France and Italy had similar

problems in Syria, Cilicia and Adalia. The only country who provided some

support through active operations at the Turkish western front was Greece.

But Greek military support was not sufficient to ease Turkish pressure on

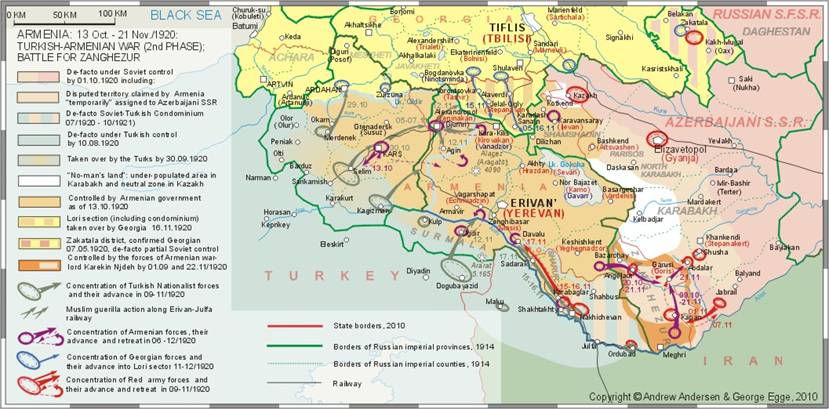

Armenia. As a result of the new Turkish

offensive the strategic town of Agin south of Alexandropol fell to the Turks

on November 12, and the Armenian troops were in retreat to the east along

Alexandropol – Karaklis railroad. The same day Armenian troops and population

started evacuation from Surmala crossing Aras river near Echmiadzin[15]

(see Map 10). At this point the Turkis were getting ready

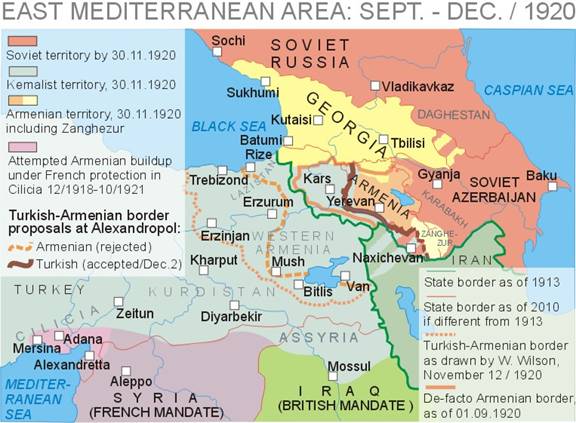

for the final spurt on Erevan. Ironically enough, it was the beginning of

November when US President Wilson was done with the final sketches of the

Sevres-based Turkish-Armenian borders[16]

(see Figure 3.4). Next day the troops of Georgia

took over the Neutral Zone (the Shulavera Condominium) established between

the two countries in early 1919. The Government of Armenia gave permission to

that Georgian action in order to prevent the occupation of this disputed

territory by the Turks. However, the Georgians marched a bit further

southwards taking over the whole of the former Lori sector which Tbilisi

considered unequivocally Georgian from the first day of independence[17]

(see Map 10). After a very quick plebiscite the whole sector was annexed by

Georgia to stay within that country for another twelve months[18].

We do not possess any information that would confirm or refute whether the

procedure of that plebiscite was properly organized but in any case, the vote

of local Armenian population in favor of Georgia was rather logical keeping

in mind the circumstances of the Turkish-Armenian war and the defeat of the

First Azerbaijani Republic. Incorporation into Georgia at least guaranteed

inviolability of Armenian lives and property in the sector while possible

Turkish occupation definitely meant the loss of both. It was also reported

that on November 15 1920, Turkish Nationalist envoy in Tiflis, Colonel Kiazim

Bey gave the Georgian government guarantee of Georgia’s territorial integrity

as the reward for her neutrality in the Turkish-Armenian war and ask to grant

his country an exclusive right for the railroad sector from Sanain to the

Azerbaijani border at Poily[19].

It might be important to mention here that Georgian annexation of the

territories claimed by Armenia were never subjected to any forms of ethnic

cleansing unlike the Armenian territories taken over by Turkey and, to a

certain extent, Azerbaijan. In the middle of November the

new Turkish offensive started in the direction of Erevan from Nakhichevan. In

breach of the Soviet-Armenian Treaty of August 10, the Nakhichevan

expeditionary corps contained the components of the Soviet 11th

Army. Between November15 and 16 demoralized Armenian troops left Shakhtakhty

and all of Sharur with little or no fight and stopped Soviet-Turkish

offensive only at Davalu on November 17 1920[20]

(see Map 10). The only war theater where

Armenians had significant success was Zanghezur. In that mountainous county

Armenian forces of Colonel Njdeh successfully repelled another Soviet-Azerbaijani

invasion from Jabrail in early November and on November 09 started

counter-advance towards Goris (Gerusy). By November 22 the Armenians of

Zanghezur assisted by an expeditionary corps from Daralaghez completely

defeated the Soviet forces of General Pyotr Kuryshko (who replased

Nesterovsky in late October, 1920) and re-took the towns of Goris, Tatev,

Darabas and Angelaut expelling the reds out of the county as far as Abdalar

near the old administrative border of Karabakh[21]

(see Map 10). Map 10. Click on the map for better resolution

The

Treaty of Alexandropol, 02.12.1920 Facing total collapse of the

First Republic, the leadership of Armenia requested an armistice for the

second time during the war, and on November 18 1920, a cease-fire agreement

was concluded[22]. A

week later, on November 24, Armenian and Turkish representatives started

peace negotiations in Alexandropol. As a precondition for any talks, the

Armenian delegation headed by Alexander Khatisov was forced to renounce the

Treaty of Sevres[23].

After having complied with that demand under pressure the Armenians presented

their border proposal. Giving up most of the former Turkish Armenia including

the cities of Bitlis, Erzurum and the coastal city of Trebizond granted at

Sevres the the delegation of the Armenian Republic asked for the small parts

of the vilayats of Van and Bitlis with the cities of Van, Bayazet, Mush and

Khnys as well as for the narrow corridor in Lazistan with the town of Rize.

As for the former Russian Armenia, the Armenians hoped to keep the whole of

the province of Erevan and the territory of Kars[24]

(see Figure 3.5). The Armenian proposal was

flatly rejected by the Turkish delegation presided by General Nizam Karabekir

Pasha as absolutely non-realistic and even insulting. Instead, the Armenian delegation

was to accept unconditionally the Turkish provisions that were quite severe. Armenia

was to disarm most of her military forces and cede more than a half of her

pre-war territory. All of the Kars territory with the districts of

Sarykamysh, Kars, Kaghyzman, Olti and the Armenian sector of Ardahan district

was to be ceded to Turkey, as well as the county of Surmala in the province

of Erevan with the city of Ighdyr and Mount Ararat. The county of Nakhichevan

combined with the Sharur sector of the county of Sharur-Daralaghez were to be

placed under Turkish protectorate (see Figure 3.5).

Self-explanatory, Armenia was not receiving any parts of the Turkish Armenia

that was now referred to as “Eastern Anatolia” by the Turks. The Armenian

Republic was also supposed to limit her relations with the Allied Powers[25].

According to Karabekir, the Turkish-drafted border between Turkey and Armenia

was based on “ethnical principle” that could not justify incorporation into

Armenia of any territories where Armenians had not formed majority before the

outbreak of the First World War[26].

Figure 3.5 At 2 o’clock in the morning on

December 3, the new peace treaty between Turkey and Armenia was signed in

Alexandropol by Karabekir and Khatisov. At the very last moment the Armenian

delegation attempted to reach agreement on a few border adjustments that

would leave Armenia with Sharur-Nakhichevan, Mount Ararar and the ruins of

Ani (mediaeval capital of Armenia) in the district of Kars, but their Turkish

counterparts were inexorable. The only concession granted to the Armenians

was some smaller territories in Aghbaba sector of the district of Kars to the north-west of Alexandropol[27].

The new Armeno-Turkish border was drawn, and it virtually never changed up to

these days.

While the Armenian government

was trying to terminate the lost war against the Kemalists begging the enemy

for peace no matter how harsh and humiliating its conditions could be, the

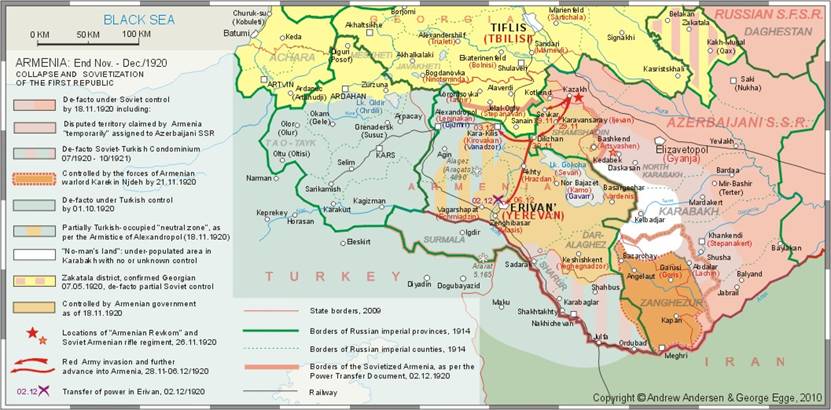

Soviets were taking over what was left of the First Republic. As early as on November 19

1920, the Soviet plenipotentiary in Erevan Boris Legran and his staff started

the arrangement of the bloodless Sovietization of Armenia following the

instructions from the Kremlin. The Dashnakist leadership of Armenia were to

be persuaded that that would be the only way to save Armenian people as well

as some form of the Armenian statehood[29]. At the same time, the Kavburo in Baku dominated by

Orjonikidze and Stalin was more impatient about the rapid conquest of

exhausted Armenia than Lenin and Chicherin in Moscow. Contrary to the

instructions coming from their communist party bosses from the Central

Committee in the Kremlin, the Caucasian Bolsheviks formed the Armenian Revkom (Military Revolutionary

Committee) in Baku on November 22, 1920, that was designed to become the new

communist government of Armenia. Three days later the Revkom departed for

Kazakh were the units of the Soviet 11th Army under General Kuryshko (just

recently defeated in Zanghezur) were preparing for the invasion of Armenia.

Same day the “Special Armenian Rifle Regiment” previously stationed in

Kedabek was re-deployed to Kazakh as well. The invasion started o the night

of November 28-29 by crossing the demarcation line between Armenia and Soviet

Azerbaijan south-east of Kazakh in the direction of Karavansaray and Sevkar

(Karadash). The two towns fell into the hands of the Reds after some

resistance on behalf of Armenian border guards and militias was crushed by

the end of November 29. The attempts of Armenian General Seboukh (Arshak

Nersisian) to organize counter-offensive from Dilijan failed due to the

unwillingness of the Armenian soldiers to fight one more war against superior

enemy, and on November 30 the Red Army was already in Dilijan from where the

Sovietization of Armenia and the overthrow of the Dashnakist government was

proclaimed[30].

Later, the soviet historians portrayed that military operation as a

“communist uprising of November 28 in the district of Kazakh”[31]

(see Map 11). The Soviet invasion from Kazakh

not only shocked the Armenian government but greatly confused Boris Legran

who had not been informed on those plans of the Kavburo. Nevertheless the

reaction of the Soviet envoy was quick and effective. By December 2, Legran

successfully pressured the Parliament and the Cabinet of Simon Vratsian to

step down and officially transfer the whole power to General Dro pending the

arrival of Revkom to Erevan. Two

days later, on December 4, Dro left Erevan for the lake Sevan area where he

welcomed the Revkom and, in turn,

gave up his power to the new Bolshevik administration. Two more days later,

the first units of the red Army entered the Armenian capital[32].

That was the end of the First republic, and independent Armenian statehood

was interrupted for more than 70 years until August 1991. The Sovietization of Armenia

was accompanied by some events that at first sight, looked like the

resolution of the territorial dispute over Karabakh, Zanghezur and

Nakhichevan. As has already been mentioned above, the Soviet takeover of some

territories claimed by both Azerbaijan and Armenia did not necessarily imply

their official status. The documents and governmental correspondence of the

described period proves that Soviet envoys in the South Caucasus used to

promise the disputed territories to Azerbaijan while talking to the new Soviet

leadership in Baku or the Kemalist representatives, and to Armenia as a price

for her Sovietization when talking to Armenian communists. Sometimes they

went so far as to make absolutely unrealistic proposal according to which “no

single Armenian village will be given to Azerbaijan while no single Muslim

village will be given to Armenia”[33].

But while promising territorial concessions to all potential allies the

Kremlin tried to keep Karabakh, Nakhichevan and parts of Zanghezur as long as

possible under Soviet Russian military administration[34]. The Power Transfer Document

compiled on December 2 1920, and published in 1928 In Moscow and Paris

contained Paragraph 3 that defined the territory of the Sovietized Armenia as

recognized by the Russian Soviet Government. It included the whole of the

province of Erevan with the counties of Surmala, Sharur-Daralaghez and

Nakhichevan, Southern sector of the county of Borchalo in the province of

Tiflis, the whole of the county of Zanghezur in the province of Elizavetpol

and parts of the county of Kazakh and the territory of Kars that were not

clearly defined[35]

(see Map 11).

Ironically enough, neither the last Dashnakist government, nor the first

Soviet administration in Erevan could boast effective control even over the

half of the above territory. However, the above document is important in

terms of serious territorial concessions that the Kremlin was prepared to

offer Armenia at the very first stage of her Sovietization. Just the day before, on

December 01, 1920, a few hours prior to the power transfer in Erevan and two

days after the declaration of the Sovietization of Armenia by the

Kazakh-Dilijan Revkom, the Soviet

government of Azerbaijan (also referred to as Azrevkom) sent its greeting to its Armenian accomplices and

declared that from the moment of the fall of “the Dashnakist regime”, the

Soviet Azerbaijan was giving up the disputed territories of Karabakh,

Zanghezur and Nakhichevan in favor of the Soviet Armenia[36].

That act of the Soviet leadership of Azerbaijan was later revoked as will be

described below, but it was widely used by the Soviet propaganda to create a

myth that only the Bolsheviks with their “communist internationalism” have

proven to be the only power in the world capable to resolve long and violent

territorial disputes like the one between Armenia and Azerbaijan[37]. Map 11. Click on the map for better resolution |

|

|