|

|

|

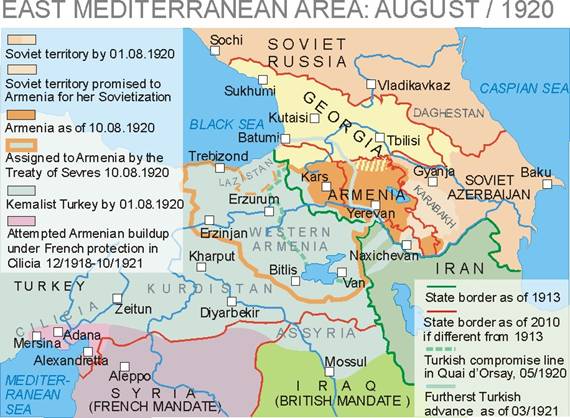

The Beginning of Soviet Expansion and the Treaty of Sevres By Andrew Andersen and Georg Egge

|

|

|

|

The Evacuation of the British troops from

the South Caucasus that started in summer of 1919 and finished in the middle

of summer of the year 1920[1] and

the Soviet blitzkrieg of April, 1920,

against Azerbaijan followed by the rapid Sovietisation of that country

performed with the help of Turkish Nationalists[2] signalled the

beginning of an undeclared Soviet-Armenian war that lasted more than FIVE

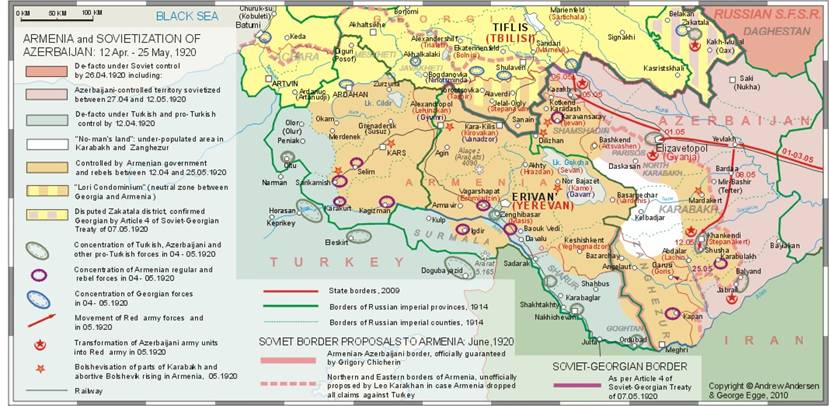

months and resulted in the loss of most of the disputed territories[3]. The first decade of May 1920 was marked by

the Soviet 11th Army advance toward Karabakh, Gandzak and Kazakh

(see Map 7). In

view of the approaching Soviet troops most of the units of the Azerbaijani

army as well as the members of the Azerbaijani administration quickly

transformed into the Red Army and Soviet bureaucracy swearing allegiance to

the new dominant power of the region[4].

Most of the Turkish officers stationed in Azerbaijan also went to Soviet

service including Nuri Pasha[5].

On May 12 the first Soviet detachments reached Shusha having the directive to

take over the whole of Mountainous Karabakh, Zanghezur and Sharur-Nakhichevan[6].

A week later after a few skirmishes Armenian General Draw whose troops still

controlled Dizaq and most of Varanda was given an ultimatum to withdraw. By

that time most of the Armenian militias in Jraberd, Khachen and Gyulistan

became rather pro-Soviet under the influence of Bolshevik propaganda. As a

result, all the Armenian officers and instructors there who refused to surrender

to the Soviets were killed, arrested or expelled and the whole

Armenian-controlled part of Karabakh to the north of Soviet-dominated

Shusha-Khankendy-Askeran corridor was lost to the Soviets. In view of the

loss of the above territory, as well as the change in sentiment even among

Varanda and Dizaq Armenians and bad communication with Erevan, General Dro

and his Staff decided to comply with the Soviet demands, and on May 25-26 all

regular Armenian forces still in Karabakh withdrew to Zanghezur. After the

evacuation the evacuation of the Armenian troops of Dro and Njdeh, only few

isolated groups of Armenian fighters kept conducting guerilla operations in

the mountains of Karabakh[7]. However, since the end of May 1920,

Mountainous Karabakh now united under the Soviet red banners was administered

by the two Revkoms: Muslim-dominated one in Shusha and Armenian-dominatred in

the village of Taghavard[8]. Map 7. Click on the map for better resolution The situation in the north-western section

of Armeno-Azerbaijani frontier was even more complicated (see Map 7). The county of Kazakh faced open Red Army

incursions into Armenian-controlled territory in attempts to support the

abortive communist uprising of May 1920[9].

The attempted communist coup in Armenia (May 10-30, 1920) was unsuccessful.

Although Armenian communists managed to take over the towns of Alexandropol,

Kars, Sarakykamysh, as well as several villages in disputed Kazakh-Shamshadin

area, the uprising was put down by the government troops and militias in less

than a month. However, it undermined the efforts of Armenia to withstand

Soviet invasion and led to the series of military defeats in

Kazakh-Shamshadin and Karabakh[10]. At the same period of time quite confusing

was the development of events in the county of Elizavetpol (Gyanja/Gandzak).

According to Kadishev, facing little resistance on behalf of disorganized and

demoralized Azerbaijani army Armenian troops and guerillas took over all of

the mountainous sector of the county reaching the outskirts of Gyanja[11].

The situation was further complicated by some facts of joint Soviet-Armenian

operations against Azerbaijani rebels during an abortive anti-Soviet uprising

that occurred in and around Gyanja at the end of May 1920[12].

As of today, it is not very easy to define where exactly stretched the limits

of de-facto Armenian control in Kazakh-Shamshadin and Gandzak-Parisos in late

spring of 1920. Some official documents of that period of time, define some

portions of that border quite clearly making modern researchers quite

confused. As an example, one can adduce an excerpt from the text of the

Soviet-Georgian Treaty of Moscow signed on May 07, 1920, according to which

the border between Georgia and Soviet Azerbaijan “…goes along the eastern

border of Zakatala district to the south until it touches the border of

Armenia”[13]. The

above excerpt clearly states that Armenian territory near the city of Gyanja

at least for a while could have stretched until the river of Kura. Soviet-Armenian

Negotiations in Moscow and the Summer Campaigns in Armenia, 05/1920 - 08/1920 The first sessions of negotiations seemed

to be moderately favorable to the Armenians. Chicherin assured Shant that the

Soviet Russia had no plans to invade Armenia or to establish a Soviet regime

in that country. Chicherin even

offered that Soviet Russia would take

a role of a mediator in Armenian territorial dispute with the Turks keeping

in mind close cooperation between Moscow and Turkish Nationalist de-facto

government of Kemal Ataturk. The Armenians were promised a part of Western

(Turkish) Armenia roughly corresponding with the initial proposal by Berthelot (see above)[15].

As for the border conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan the initial Soviet

proposal was to leave Zanghezur and Sharur-Nakhichevan with Armenia while declaring

Karabakh a disputed territory the future of which would be defined by

plebiscite[16]. One should keep in

mind here that Chicherin "graciously" offered the Armenians to keep

only those territories that were not yet sovietized. As will be mentioned below,

the format of Soviet proposals kept changing while the Red Army was taking

over new Armenian-claimed territories. The Armenian delegation was also deeply

impressed by the map of a projected Armenian state that was unofficially

demonstrated to them by Karakhan. The map presented by the Bolshevik diplomat

was offering the Armenians not only all the territories disputed with

Azerbaijan (including Mountainous Karabakh) but also most of Borchalo, the

counties of Akhalkalaki and Akhaltsikhe (the latter never claimed by Armenia)

and the Chorokh-Imerkhevi corridor to the Black sea (see Map 7), i.e., the

territories that the Soviets recognized unequivocally Georgian by signing the

Soviet-Georgian treaty in early May 1920. After being reminded of that

Karakhan replied that the question of Georgian territorial integrity was

“still open”[17], and significant

concession could be given to Armenia if only the Armenians dropped all or at

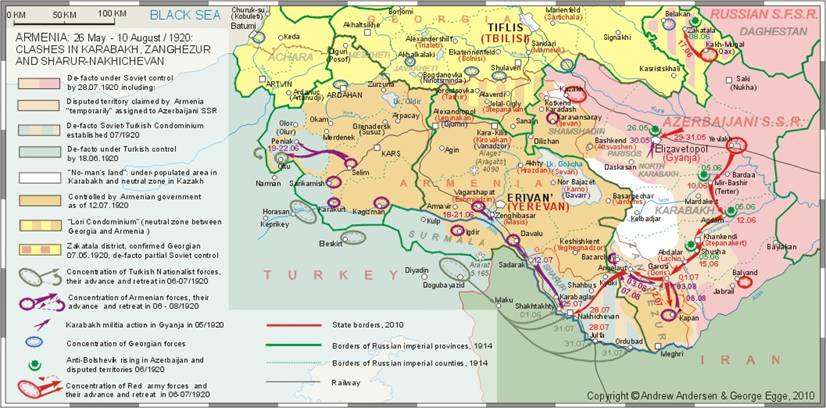

least most of their aspirations against Turkish territory. During the first phase of Soviet-Armenian

negotiations in Moscow, the 11th Army was busy putting down anti-Soviet

Azerbaijani rebellions in Gyanja, Zakatala and Agdam-Shusha while Armenian

forces were similarly busy with crushing Bolshevik uprisings in Kars,

Sarikamysh, Alexandropol, Nor-Bayazet and Delizhan and later pacifying

rebellious Muslim enclaves in Zenghibazar, Vedibazar and Peniak[18]

(see Map 8). By mid-June the Soviet tone at negotiation

changed drastically. If earlier the Red Army was unable to invade

Zanghezur-Nakhichevan being tied up with Azerbaijani uprisings but after the

fall of Shusha on June 15, the way to Nakhichevan via Gerusy (Goris) was

open.[19]

Gerusy was taken by the Reds on July 5, and on July 17 the 11th

Army started advance towards Nakhichevan while at the same time the

detachments of Turkish Bayazet division in the amount of 9000 trespassed

Iranian territory north of Khoy and concentrated in Maku. Those Turkish

forces under the command of Jevad Bek were preparing to cross Aras river and

enter Nakhichevan, Julfa and Ordubad from the south-west in order to block

further re-conquest of the Nakhichevan county by Shelkovnikov’s Armenian

troops who had already reached Shakhtakhty by July 25 (see Map 8)[20]. Reflecting rapidly changing military

situation at Soviet-Armenian frontier, Chicherin now proposed that the new

boundary would run along the administrative border between the old provinces

of Erevan and Elizavetpol thus leaving Nakhichevan to Armenia, Karabakh to

Azerbaijan and Zanghezur under "temporary" Soviet administration as

a disputed territory. At some point Influenced by Sergo Orjonikidze (at that

time the Chairman of Kavburo of Russian Communist Party), Chicherin and

Karakhan even proposed to include Sharur-Daralaghez county into the list of

disputed lands. The Armenian delegation was not prepared to accept permanent

loss of Karabakh not to mention the questioning of the status of

Sharur-Daralaghez, and after some fruitless discussions the talks were

suspended[21]. The Red Army was

meanwhile fighting Armenian militias in Zanghezur in order to capture Gerusy[22].

It may be important to mention here that immediately after the Soviet -

Armenian negotiations were interrupted Chicherin started the talks with Foreign

Affairs Commissar of the Turkish Nationalist government in Angora Sami Bey

who arrived in Moscow to arrange joint Soviet - Turkish operations in

Nakhichevan aimed at opening a stable land corridor between Soviet Russia and

Nationalist Turkey[23].

One of the few results of the interrupted Soviet-Armenian negotiations was

the appointment of the lawyer Boris Legran a Soviet plenipotentiary in

Armenia who was supposed according to Chicherin, to finish the negotiations

with the Armenian government directly in Erevan. While Legran’s mission was slowly making

his way to Erevan with prolonged stops at Baku and Tiflis marked with the

exchange of proposals with the Armenian government, the Soviet-Armenian

warfare escalated in Zanghezur. After having taken over Gerusy in early July

1920, the Soviets established the red terror regime in the north of Zanghezur

and in the middle of the month tried to expand southwards in an attempt to

sovietise the whole county (see Map 8). However, the

first Soviet expedition into the heart of Zanghezur ended up in fiasco by the

beginning of August. Defeated by the militias of Njdeh near Kapan and

attacked by the regulars of Dro in the rear from Angelaut the components of

the 11th Army rapidly evacuated Northern Zanghezur and retreated

into Varanda[24]. Following Dro’s

ultimatum to clear “all occupied Armenian territories” including Karabakh,

the Soviets started counter-offensive on August 05, and two days later Gerusy

was lost by the Armenians for the second time. The Shusha-Gerusy-Nakhichevan

corridor vbetween Nationalist Turkey and Soviet Azerbaijan was re-opened, and

both Turkish and Soviet officers celebrated that victory as partners[25]. Meanwhile, in the county of Nakhichevan

Soviet-Turkish and Armenian troops facing each other halfway between

Nakhichevan and Shakhtakhty tried to abstain from open hostilities following

verbal “Gentlmen’s agreement” between Armenian General Shelkovnikov and “the

commander of the united troops of RSFSR and Red Turkey”, Colonel Tarkhov[26].

On July 28 “Soviet Socialist Republic of Nakhichevan” was proclaimed, and its

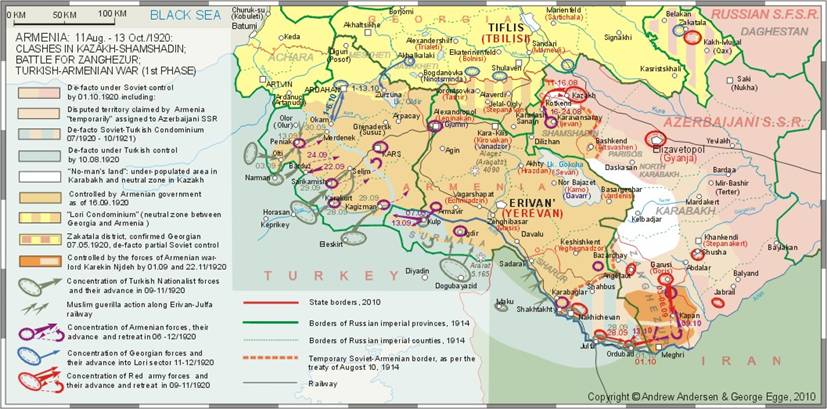

“Revolutionary Committee” offered Erevan to recognize the new “independent state”. Map 8. Click on the map for better resolution On August 10 1920, the cease-fire agreement

was signed in Erevan by the representatives of Soviet and Armenian

governments leaving Armenia without most of the disputed territories but

temporarily ending major hostilities along Soviet-Armenian front-lines. As

per the agreement, the temporary south-eastern border of Armenia was defined

as follows: “Shakhtakhty-Khok-Aznaburt-Sultanbek

and further the line northward from Kyuki and westward from Bazarchai

(Bazarkend). And in the county of Kazakh – the line they hjeld on 30 July of

this year. The troops of RSFSR will occupy the disputed districts: Karabakh, Zanghrzur

and Nakhichevan, with the exception of the zone determined by this treaty for

the disposition of the troops of the Republic of Armenia… The occupation of

the disputed territories by the Soviet troops does not predispose the

question about the rights to those territories of the Republic of Armenia or

the Azerbaijan Socialist Soviet Republic. By this temporary occupation, the

RSFSR has in view the creation of favorable conditions for the peaceful

resolution of the disputed territories between Armenia and Azerbaijan on the

principles to be laid down in the peace treaty to be concluded between the

RSFSR and the Republic of Armenia as soon as possible” [27]

(see Maps 8 and 9). Thus the Soviet

negotiators assured their Armenian counterparts that the occupation of the

disputed territories by the Red army did not necessary mean their annexation

by Soviet Azerbaijan but was of a temporary character and would not last only

until the future peace treaty is concluded by all the involved parties to

resolve all the border disputes. Armenia was also given ex-territorial rights

for the Shakhtakhty-Julfa section of Erevan-Julfa railway[28]. According to

Hovannisian, the preliminary treaty between Soviet Russia and Armenia was a

result of Soviet bogging down in the war against Poland and the anti-Soviet

government of Baron Wrangel as well as the dangerous anti-soviet uprising in

Kuban[29].

In any case, that treaty gave Armenia 22 days of peace interrupted

only by sporadic attacks on Sadarak-Karabaglar section of Erevan-Julfa

railway performed by Muslim irregulars from Persian territory (see Map 9). After August 10, some fighting also

continued in Zanghezur where the Armenian forces under Lieutenant Colonel

Garegin Njdeh refused to evacuate and the mountainous area of southern

Zanghezur between Gerusy (Goris) and Meghri which they kept under stable

control even after the August counter-offensive of Soviet General Nesterovsky[30].

The guerillas of Njdeh kept their formal loyalty to the Republic of Armenia

and were getting some support from Erevan but that support was of rather

private than official nature. Map 9. Click on the map for better resolution The

Treaty of Sevres, 10.08.1920 The Treaty of Sevres legally satisfied less

than 40% of Armenian claims in Western Armenia. Article 88 of the Treaty gave

international recognition to the Democratic Republic of Armenia as a

sovereign and established nation, whereas a Article 89 gave Armenia the

vilayat of Erzerum, half of the vilayats of Van and Trebizond and almost all

of the vilayat of Bitlis delegating the decision regarding the exact borders

between Armenia and Turkey as well as Armenia and Georgia, to the President

of the United States (see Figure 3.4). As can be seen from the below quotation of

Article 89 (Section IV, Part III) of the draft piece treaty with the Turkey,

it lacked clearance regarding the future Turco-Armenian border delegating the

final decisions to the US President: 89. Turkey and Armenia as well as the other

High Contracting Parties agree to submit the arbitration of the President of

the United States of America the question of the frontier to be fixed

betweenTurkey and Armenia in the vilayats of Erzerum, Trebizond, van and

Bitlis[32]. The treaty contained even less clearance in

regards with the borders between Armenia and her South Caucasian neighbors.

In accordance with Article 92: 92. The frontiers between Armenia and

Azerbaijan and Georgia respectively will be determined by direct agreement

between the States concerned[33].

Figure 3.4 |

|

|