|

|

The

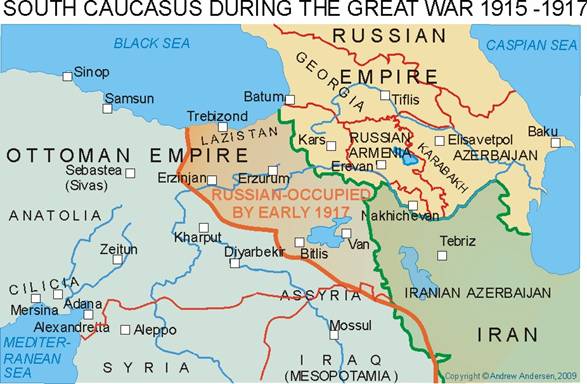

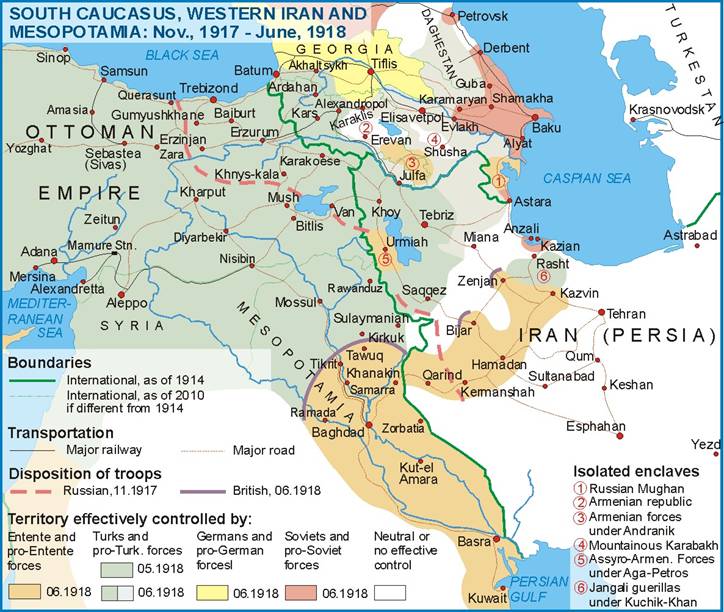

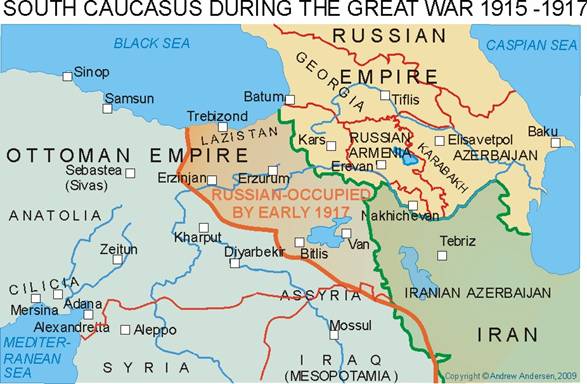

advance of Russian armies in Western Armenia

in 1915-16 did not give much hope for the restoration of Armenian statehood.

However, at that time it seemed quite realistic that the majority of Armenian

core lands would be united under Russian sceptre.

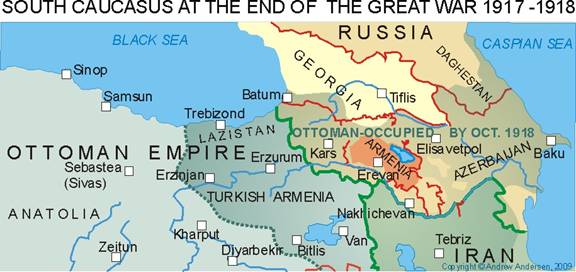

Figure 2.1

Figure 2.1a

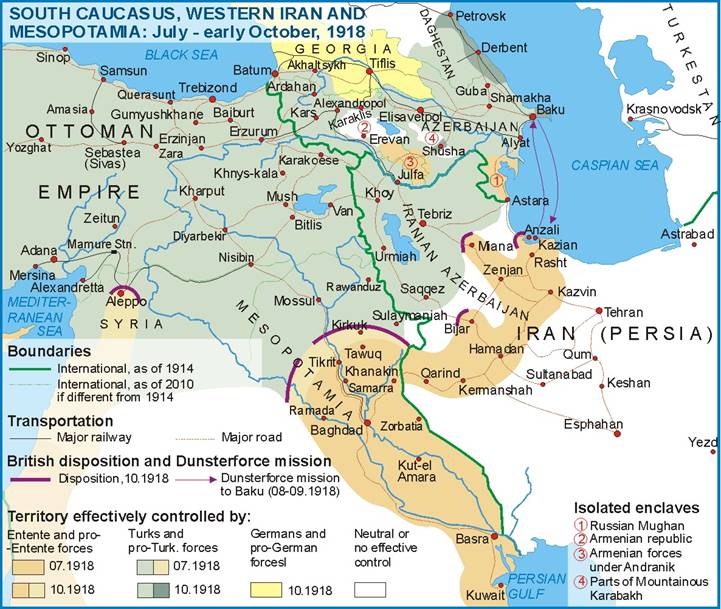

All those hopes started vanishing in early 1917 as the

Russian Empire collapsed and so did the Caucasus

front. The planned operations for further advance were put on hold, the old

commanders were dismissed and left the Caucasus Army and the new command kept

awaiting new instructions from the republican government that never came.

Meanwhile, the Russian Caucasus army entered the stage of decay due to

inactivity, poor supply and the collapse of pre-revolutionary system of

seniority and discipline. The whole units started self-willed evacuation.

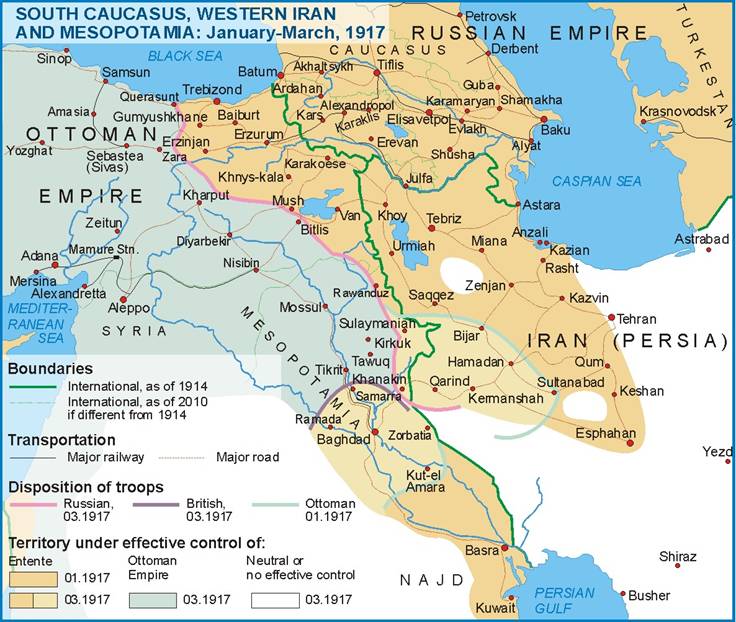

Under those circumstances, the cease-fire Agreement signed between Russia and Turkey

on December 19, 1917 could postpone but by no means prevent Ottoman

re-conquest of Armenia

that started in early 1918.

One should add to the above that the change of regime in Russia was

accompanied by at least one breakthrough in the frozen Armenian question: On

April 25, 1917, the Decree of Russian Provisional Government finally allowed

the refugees from Turkish Armenia to move back to their abandoned homes in

Russian-occupied areas. However, that permission came too late. Less than 200

000 refugees attempted to return to devastated Western

Armenia and even lesser amount actually re-settled there.

On the 12th of February, 1918, the Turks began recapturing

the territories they had previously lost to the Russians and their Armenian

collaborators, simultaneously massacring any remnants of the Armenian

population they could still find in Eastern Turkey.

In the vacuum that remained as a result of the Bolshevik coup, the leading

political parties of South Caucasus started

seeking independence of the disintegrating Russian empire in a desperate

attempt to prevent anarchy and protect the area from the Ottoman menace. The

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk signed on March 3, 1918, between Soviet Russia and

the Central Powers confirmed Ottoman sovereignty over Western

Armenia. The Soviets also agreed to cede to the Ottoman Empire

the districts of Batum, Kars,

Ardahan, Oltu and Kaghyzman. Refusing to accept the provisions of the

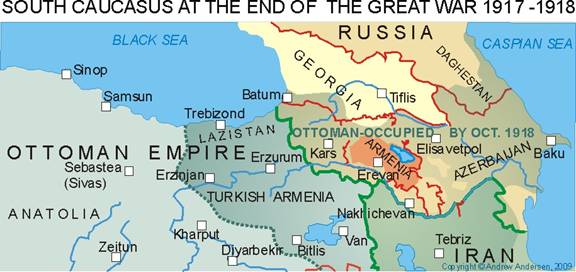

Brest-Litovsk Treaty the Armenian- and Georgian-dominated political

leadership of the South Caucasus chose to continue the war and on April 22

proclaimed in Tiflis the independence of

Transcaucasian Federal Democratic Republic (TFDR). By that time all Western

Armenia except Van was lost to the Turks and the Ottoman armies crossed the

pre-war border advancing Kars

and Batum. After a series of military defeats, TFDR agreed to accept the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk but this time its provisions did not seem to satisfy

the Turkish government any longer and in early May, 1918 a peace conference

opened in Batum. The conference demonstrated that there was no or very little

consensus between Armenian, Georgian and Tatar (Azerbaijani) political elites

in terms of the future of the South Caucasus.

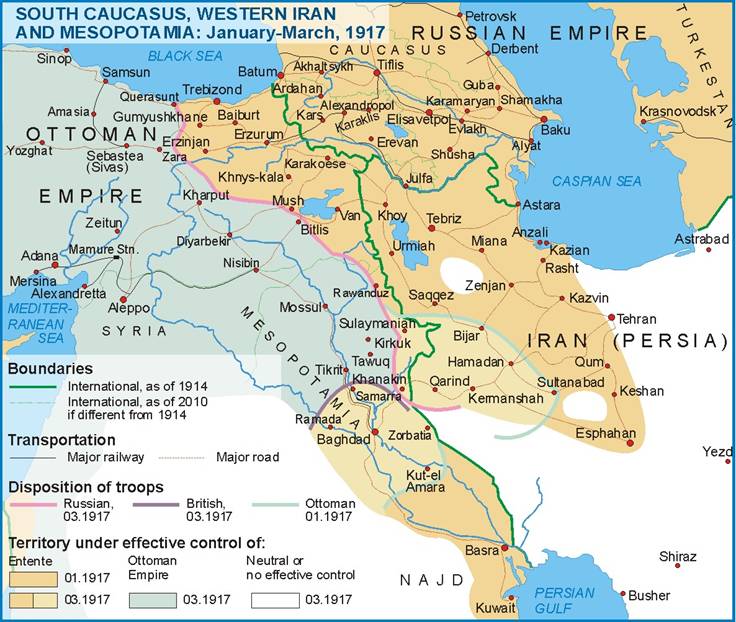

With the Tatars openly siding with the victorious Turks and Georgians

desperately seeking German protection, the isolated Armenians remained loyal

to the Entente and willing to fight for their existence as a nation.

Meanwhile despite the peace conference going on, the Ottoman armies continued

their advance until they were stopped by Georgian national Guard at the

Battle of the River Choloki (April 16-17, 1918) and by Armenian army and

militia at the battles of Sardarabad (May 21-29), Kara-Killisse (May 24-28)

and Bash Abaran (May 21-24). These military victories of the new-born

democracies in combination with some diplomatic support on behalf of the

German Empire

prevented total annexation of the Caucasus by

the Turks and saved remaining Armenian population of the area from total

annihilation.

On May 26, 1918, the Transcaucasian Federation dissolved, and 2 days later an

independent Armenian

Republic was

proclaimed. The birth of the first republic was facing economic disaster,

Turkish invasion and political isolation. On June 4, 1918, a peace-treaty was

signed in Batum, according to which considerable part of South Caucasus was

assigned to Turkey, most of Georgia remained under German protectorate and the

Armenian Republic was cut down to a tiny enclave around the cities of Yerevan

and Vagarshapat (Echmiadzin) that embraced the county of New-Bayazet as well

as the eastern parts of Alexandropol,Yerevan, Echmiadzin and

Sharur-Daralaghez counties of the province of Yerevan.

Turkey was also given

carte blanche to act in Azerbaijan.

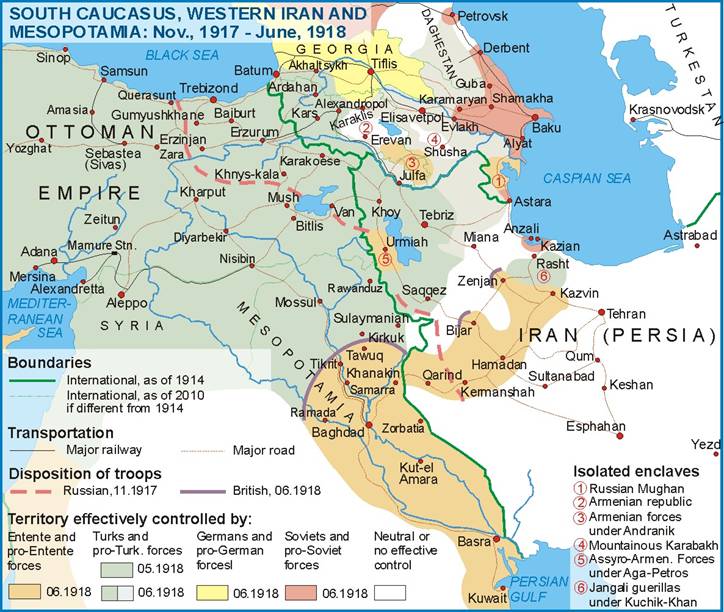

Figure 2.2

Figure 2.2a

By the end of summer 1918, Ottoman troops supported by the

mainly Tatar “Army of Islam” took over most of the territory of what could be

considered the former Russian Azerbaijan (the provinces of Baku and

Elizavetpol) and marched into Baku where they massacred between 10 and 30,000

Armenians still residing in the city.

In late September, 1918, once-cosmopolitan Baku

became the capital of the new Azerbaijani state proclaimed earlier on May 28,

1918 in Tiflis.

Meanwhile, contrary to the provisions of the Treaty of

Batum, some Armenian troops under general Andranik continued guerrilla

operations against the Turks from the mountainous area of Zanghezur, thus

having formed another de-facto independent Armenian quasi-state formation

there.

At the same time, the Armenian-inhabited part of Karabakh

(including its northern areas) enjoyed relative peace in August and September

of 1918 administered by the People’s

Government of Karabakh elected by the First Assembly of Karabakh

Armenians.

It was only at the very end of September when Shusha, the capital of

Mountainous Karabakh did submit to the Ottoman-Azerbaijani conquest.

As for the rural areas of Mountainous Karabakh are concerned, they formed

several enclaves (Khachen, Jraberd, Varanda, Dizak and a few smaller areas of

Northern Karabakh) that were kept under control of local Armenian warlords

until the very end of the World War.

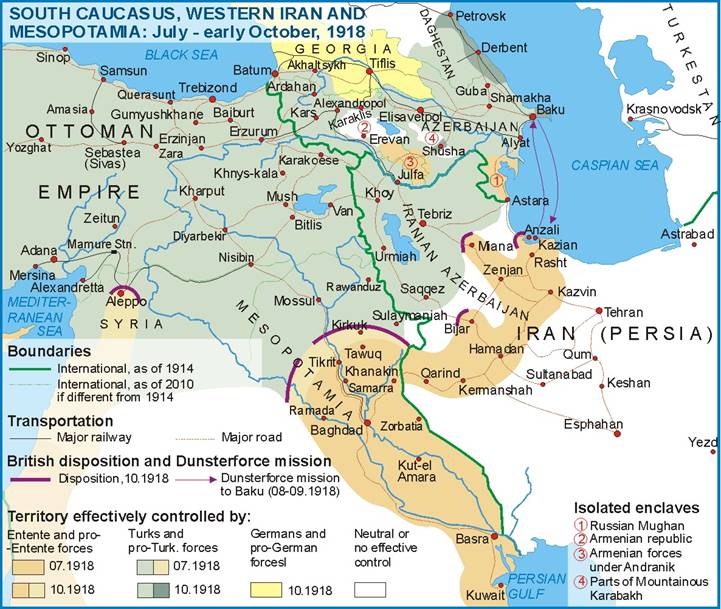

Figure 2.2b

|

|