|

Andrew Andersen LOST HOME: ARMENIAN

LIFE IN NATIONAL AWAKENING

IN THE 19TH CENTURY. The 17th and 18th

century saw the series of wars between Iran and Ottoman Turkey and several

movements of the state borders leaving Armenian lands within the two Muslim

empires. The Armenians living in barely surviving |

|

|

Flag of Armenian

Apostolic Church |

Having lost the last relicts of their

statehood, their nobility practically wiped out, their rights not protected

by the Islamic law, Armenians were emigrating en masse to Western and |

|

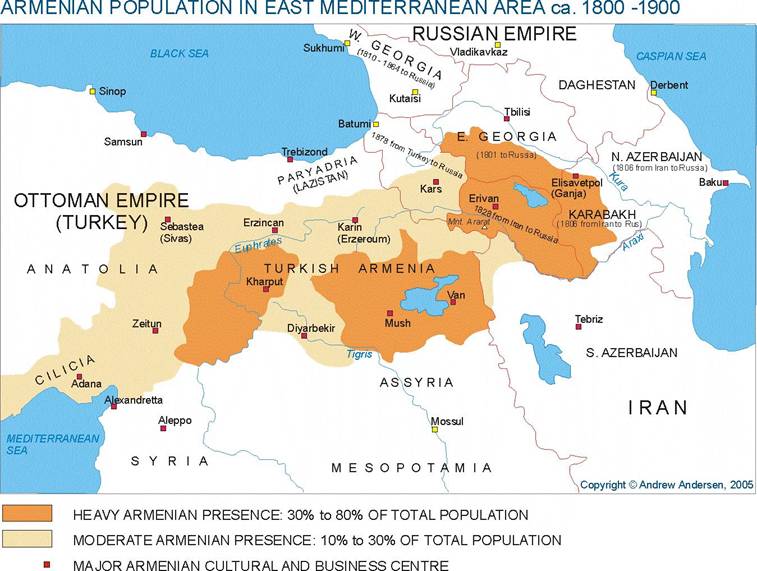

The percentage of Armenian population in

both was Ottoman Turkey and The beginning of the 19th

century brought significant geo-political changes in |

|

|

According to Luc Baronyan, the above

tricolor was the first Armenian “national flag” designed in 1885 in |

Starting with the middle of the 19th

century, various Armenian organizations, predominantly the ones with centers

in The awakening of Armenian nationalism

resulted in the creation of secret Armenian societies, among them “Salvation

Union”, “Black Cross Society”, “Armenakan” and “Protectors of the Fatherland”. Some of the above societies

were behind the Armenian uprisings in Zeytun (1862), Erzerum (1863) and Van

(1863) all of which were crushed by the Turks with extreme cruelty[i].

|

|

As an answer to the development of Armenian

nationalism and separatism, the government of The liberation of the Balkans gave new

hopes to Armenian nationalists for gaining independence through the

“Bulgarian way”. However, neither major European powers, nor At the very end of the 19th

century, new-formed socialist-revolutionary parties of Hnchak and Dashnak,

adopted a new strategy of socialist revolution in which Christian Armenians

should fight together with the poorest Muslim Turks and Kurds against the

“capitalist exploiters”. That led to partial withdrawal of support of any

revolutionary projects on behalf of Armenian bourgeoisie of Armenian revolutionaries also aimed at the

armament of all Armenian peasant population so that the peasants would be

able to protect themselves from Kurd nomadic bands and Turkish gendarmerie,

as well as to launch general uprising in the six Eastern provinces of Turkey

that were claimed by the Armenians as their historic homeland (see the map

below) and organized secret roots

|

|

|

|

of supply. However, the lack of funds and

ways to deliver the required weapons to all Armenian communities of The guerilla movement in some areas of

Turkish Armenia, also known as the Fidayee

movement, lasted till the beginning of the First World War and produced many

experienced field commanders (Duman, VArdan, Dro, Khamzasp, Sako, Krecho,

Arakel, Avo, Njde, Sepoukuh, and many others) who later became officers and

generals of Armenian army during the short independence period of 1918-1920. Many Fidayees

of Turkish Armenia also crossed the border into Russian Caucasus during the

“Armeno-Tatar War” of 1905 (violent ethnic conflict between Armenian and

Azeris in |

|

|

|

Mauser pistol was

the favorite weapon of Armenian city

guerillas in |

|

|

The Turkish-Armenian confrontation finally

reached its culmination in the year of 1915 when |

||